1970 Nomad-BRM Mk3

After the war years in the UK, a certain Churchillian spirit prevailed, which left many with an upbeat feeling, believing there was no goal too great, no mountain too high to attempt. It was just a question of self-belief and tenacity. Indeed, in typical inspirational mode, Sir Winston Churchill once said, “Attitude is a little thing that makes a big difference.” This optimistic state of mind lasted for a couple or more generations, but sadly appears severely lacking today. Politically speaking, that mindset seems to have gotten lost in the 21st Century, the UK’s Brexit vote has left nearly half a nation deliberating on how Great Britain will manage without the crutch of the European Union, but enough about politics. Post-war motor racing teams and individuals—privateers to be correct—thought nothing of building their own competition car to compete in whatever series or formula they could, despite having very limited financial means. They were the “underdogs.” Motor racing finances during the late 1950s and early 1960s were very different too.

In European racing, there was very little sponsorship money about, although bigger teams would have fuel and tire company backing without the necessary on-car advertising—most cars raced in national colors in international races and team or individual colors in national events. At that time, motorsport was considered an entertainment, so just like any theatrical performance there was good “box office” money for the stars of the show on a sliding scale even down to the “also ran” at the back of the grid. Starting and prize money allowed some to make a meager living out of the sport, while others who had a reasonable pot in the first instance raced for the love of it. However, the adage “how do you make a small fortune out of motor racing? Start with a big one,” still applied.

Sports car racing, in particular, was made up of a peppering of Grand Prix drivers among the regulars—drivers were more like jockeys in those days, switching from car to car, race to race, and would regularly appear on three or four grids during a day’s racing schedule. Again, unlike today, privateers could enter the big international events as well as national races. Regulations, although tight, were still in a somewhat embryonic state and much more encompassing and forgiving way back then, despite the many hazards and perils. Danger was considered an integral part of the sport, which both participant and spectator alike were all too aware of. Health & Safety risk assessments, for better or worse, were simply not on the agenda.

Photo: Mike Jiggle

All drivers knew the risks involved in hard competitive driving, but obviously no one wanted to get injured, or see fellow competitors come to any harm. There was a great camaraderie between teams and drivers, each would help another if they could. Drivers didn’t wish to see a diluted grid; to be the best, you had to beat the best. Lending spare parts, engines, gearboxes, or even spare cars was not unheard of—fellow mechanics would lend each other a hand too. After full sponsorship became the order of the day, the whole racing scene changed, today with hindsight, many agree not for the better. Corporate money and political intervention soon put a stop to the fellowship and esprit des corps of old. Winning at whatever cost has become the modern racing ethos, and politics play a much bigger part of the game. It’s easy to see how out of this the fabled “Piranha Club” was born.

Like the Formula One World Championship in 1950, post-war sports car racing was granted World Championship status, starting in 1953, by the sport’s governing body. Major motor manufacturers saw this championship as a great marketing tool to boast about their particular marque. Obviously, the 1955 Le Mans disaster was a severe blow to the burgeoning series. Time being a great healer, the world watched the championship not only survive, but flourish to an extent where it became as important, if not more so, than Grand Prix racing. Certainly, the man in the street seemed to identify with sports car racing more than Formula One. Major manufacturers saw motor races as simply bait to draw in roadcar customers, “Win on Sunday, sell on Monday,” as we’ve mentioned many times before, was the reward for racing success and the raison d’etre for intense investment by the major marques of the day.

Jaguar and Aston Martin had been at the forefront of a British-led invasion, with Jaguar taking five Le Mans victories from 1951-1957 and Aston winning in 1959. It was this success that ignited and stimulated the growth of the enthusiastic British professional and amateur constructor, no matter how large or small. Looking back on those period paddock photos of the era, while there may be trucks and transporters of major marques, there is also a great sprinkling of smaller outfits some using converted removal vans or coaches to transport their cars to the circuit, others simply had a trailer. Passionate craftsmen and mechanics working a second shift after their normal working hours during the evening or at weekends, constructed many of these competition cars at the “lower end” of the scale. They didn’t work in fancy state-of-the art premises, just a simple garage at home, or a small shed, even working under a tarpaulin held up by poles was the norm for these artisans. It is fair to say that while the character, size and shape came from the minds of the individual designer/builders, engines from the major manufacturers of the day powered the vehicles they built.

From these lowly beginnings the sport grew, Colin Chapman’s Lotus, Eric Broadley’s Lola and Derek Bennett’s Chevron teams were part of these very humble beginnings, but by the mid- to late-1960s they had become something of relative powerhouses of the sport. Despite this there were still those who were prepared to have a go. Albeit that the Nomad project was a “privateer” operation, all three cars were built to FIA rules, Appendix J, Category B, Group 6, prototype sports cars, which for creators Curl and Konig were precise rules within which the cars were designed and built. These prototypes were restricted to the 1500-cc, or 2000-cc classes as the major manufacturers dominated the top class engine category, with Ferrari, Ford and Porsche investing inordinate amounts of money into their particular prototype projects.

The Nomad Project

It was American H. Ross Perot, founder of Electronic Data Systems, billionaire and independent presidential campaign runner of the 1990s who said, “Life is never more fun than when you’re the underdog competing against the giants.” It may be difficult to understand how this wealthy man could consider himself an underdog, but his fame and fortune began with a $1,000 loan from his wife way back in 1962. When Mark Konig and Bob Curl set out to build the first Nomad, they knew they’d be competing against giants (a more detailed background into both Mark Konig and Bob Curl can be found in the “Legends Speak” and “Interview” sections of this magazine). They were the typical British “garagiste” outfit against the might of the German Porsche 910s, Italian Alfa-Romeo Tipo 33s and Ferrari Dinos. As I’ve already mentioned, by that time too, the British Lotus, Lola and Chevron teams far outshone the low-budgeted Nomad project, but all were chasing places, points, podiums and prizes in the various classes up to two-liters of the World Sportscar Championship in 1967.

Against this background, on a visit to the Chequered Flag premises at Ravenscourt Park, former Lotus Elan, Elite and Ferrari 250LM driver Mark Konig was shown a model of a car Bob Curl had constructed. The model had been shown to a number of visitors to the workshops there—it was a hive of activity in a motor racing sense. Konig and Curl came to an agreement and work on the car began. Even at that time, though, many an outsider would have told them the project was a “bridge too far” and possibly doomed to failure. Money was playing a much bigger part in the sport with the advent of sponsorship, and it was the domain of the major motor manufacturers, rather than the now dying breed of privateer constructors. Don’t get me wrong, the Nomad car was impeccably designed, extremely well built and was expertly driven by Mark Konig and the very talented Tony Lanfranchi.

Nomad Mk1

The genesis of the Nomad was a mid-engine coupe-bodied car, substantially built on a multi-tubular spaceframe of 16-18-gauge square and round tubing. Curl had distinctly gone along the safety route, bearing in mind it was due to compete in the gruelling races of the Group 6 Championship, rather than mere sprint races. Curl had also witnessed, first-hand, the way fellow competitors would be driving when he had helped Konig out as a mechanic the previous year both at Spa and Nü̈rburgring, notoriously challenging race circuits. The front suspension was double wishbone with adjustable coil dampers and the rear was lower wishbone with twin radius arms, again with coil dampers. Braking was by Girling 10½ inch discs all around.

The car was originally powered by a 1.6-liter Ford twin-cam engine, with a Hewland gearbox, and later uprated to 1.8-liter, though the following year it changed to a 1.5-liter BRM engine, formerly used by the British Racing Partnership Formula One team. Williams & Pritchard constructed the original bodywork in aluminum, which again was later modified with various parts being replaced by fiberglass to save weight. Once complete, it looked like a “proper” racing car, although maybe a little large for its class. On May 22, 1967, a successful shakedown test was completed at Goodwood, a circuit that had just closed for competition. Nomad 1 was then entered in the Anerley Trophy race at Crystal Palace at the end of that month. This first race proved successful too, although a restrained drive left Konig finishing in last place—it was nevertheless a finish for the Nomad. If the first race was driven on a cautious note, the next race in France, the Auvergne Trophy 300-kilometer race, was far from that. Finishing 7th overall, it was a class win for the nascent Nomad team. Clutch failure at the Reims 12 Hours, 45 minutes before the checkered flag, brought the team’s first DNF (the French officials refused to classify the car in the results). Mugello was the next race. Konig, finishing 12th overall, won an enormous trophy for being first of the solo competitors, restoring pride after a very gritty drive. The giant cup was later filled with Tuscan wine and so the celebrations of his feat began. The 10-race first season finished on a high note as the Konig/Lanfranchi partnership finished 12th overall, but won their class at Montlhéry in the Paris 1000 Kilometers. By that time, the itinerant Nomad team had clocked up a good number of miles visiting many European circuits and satisfyingly completed more than 2,000 competition miles. Both Konig and Curl felt vindicated against any criticism, or detractors of their project.

During the winter break, despite not needing any chassis repairs or modifications, a decision was taken to replace some of the bulky aluminum body panels with fiberglass, including the nose, tail and doors. Another modification was to replace the 8½-inch rear wheel rims with broader 10-inch rims. The first race of the 1968 season was a long-haul to the Daytona 24 Hours, where the minuscule team of just Konig and Lanfranchi finished a very creditable 24th following issues with the gearbox—the car had been as high as 15th prior to the transmission problems.

This was motor racing on a shoestring taken to the Nth degree of economics! Back in “Blighty” and the car was further enhanced with a lighter Hewland FT gearbox and an 1800-cc engine. It was following these modifications that the Nomad shone at the BOAC 500 when Lanfranchi led the Alfa T33s…that was, until the crankshaft broke.

Midway through the 1968 season, the Ford twin-cam was replaced with a 1500-cc BRM engine, following the twin-cam’s demise during the race at Anderstoorp, Sweden. Bob Curl takes up the story, “We changed to V8 BRM power, but didn’t get it direct from BRM in Bourne. It was an engine formerly used by Stirling Moss’ British Racing Partnership (BRP) team, although I got it through John Wyer. I remember collecting it myself. It cost £750 for the complete engine and six-speed gearbox. I remember thinking, the engine and gearbox on board my van was worth five times more than the van—precious cargo indeed.”

Despite early overheating problems, which were remedied by fitting a bigger radiator, the new engine gave encouraging results with a 6th overall and 2nd in class at Jyllandsringen, Denmark, 5th overall at the Nü̈rburgring 500, 7th at Imola 500 Kilometers and 14th overall and 1st in class at the Paris 1000 Kilometers—the last race for Mk1 in Mark Konig’s hands.

Nomad Mk2

Photo: Peter Collins

A change in regulations for 1969 saw the abolition of a weight limit and spare wheel rule come into force. As early as October 1968, Bob Curl was designing the new car, this time a long-tail, open-cockpit design. Work started on the car just before Christmas in 1968, and was finished for its first race, the Targa Florio in early May 1969. This second car was much lighter and sported many parts of the two-liter Tasman BRM, including the suspension and wheels, but a Hewland replaced the BRM gearbox. Bob Curl and Len Sayer again carried out the work with bodywork by the very competent Arthur Rothon. Much to Mark’s delight, he was six minutes a lap quicker in the new car than the previous Nomad—truly encouraging. However, disaster struck in practice while Mark’s wife Gabriel was at the wheel. Unfortunately, given the rough surface, she got a puncture and tried to get back to the pits. The drive back damaged the suspension severely and they were out of the race.

Back home, the car was repaired and mechanic Julian Pratt joined the team to assist with race preparation. Although the next race was the Martini Trophy at Silverstone, all eyes were on the prestigious Le Mans 24-hour race and an immense battle with the “big boys.” Despite all the prep, checking this and that to the Nth degree, La Sarthe’s gremlins were at play and just before the completion of the second hour of the race a tiny screw holding the gearbox oil seal worked loose, cutting short the French adventure. Tony Lanfranchi summed up the feeling in the Nomad camp, “Colin Chapman did it. Briggs Cunningham did it, but I don’t think that too many people have actually driven in the Le Mans 24-hour race, one of the world’s greatest classics, in a car of their own creation.”

In those few hours, many aspects of the new car had been learned including its ultimate pace—170 mph achieved down the Mulsanne. The 1969 season saw the last Le Mans-type start after protests that doing seat belts up at 200 mph on the Mulsanne Straight was dangerous.

Shortening the long tail section of Mk2 gave the Nomad a Porsche-like look. Not only did this modification save weight, but it also allowed room for a wider rear wheel, Firestone shod 13-inch. The car was also given a new livery, with red replacing green. Aggravating blips and glitches blighted great qualifying performances and even Lanfranchi’s uncharacteristic 120 mph accident during the Paris 1000 Kilometers hindered potential success of the Mk 2. After a hasty repair, a 2nd place grid spot followed by a 5th overall and 1st in class was one of the car’s best performances at the Madrid Six Hours, at Jarama. Lanfranchi suffered another accident while leading his class in the 1970 BOAC 500 at Brands Hatch by a country mile.

In his book Down the Hatch, Lanfranchi recalls, “It is so vivid to me. I was coming out of Stirling’s bend, going toward Clearways, the right-hander that goes onto the pits straight. And suddenly, instead of turning right, the car turned sharp left. Ninety-degrees left! I remember Ba-ang! as it hit the bank. And that is all I do remember until I came round in a bloody ambulance area somewhere, and somebody was saying, ‘You’re all right, you’re all right.’” He continued, “It isn’t often I make excuses for a crash, but this time …. Well, you don’t normally turn left just before a right-hand corner.”

Nomad Mk3

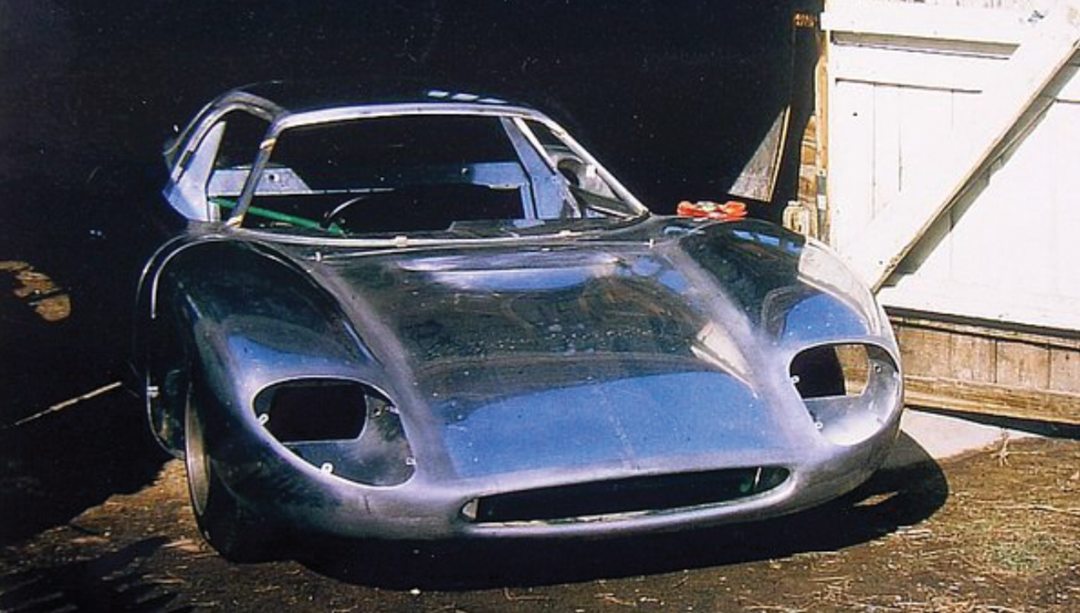

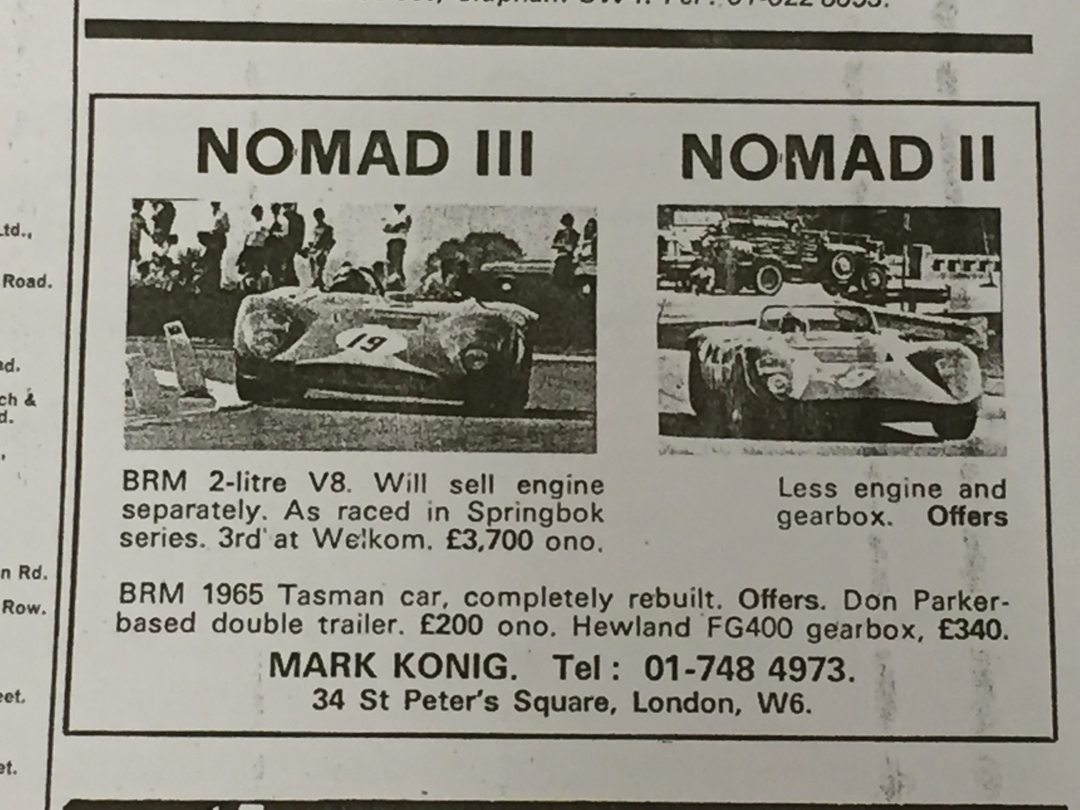

Work was well underway for the new 1970 challenger Nomad Mk3, our profile car, but although similar in design to Mk2 this was a different car. Bob Curl explains, “It was a bit more of a sprint car rather than the previous models. In essence, we’d built the car for the European 2-liter Championship. The chassis was around 15 to 20 pounds lighter, the body was pretty thin and it had a short ‘spyder’ tail.” Once again, two-liter, V8 BRM power was used and the car featured modified suspension, although still based on the BRM P261 geometry. Brabham “Indy” wheels were another weight-saving addition. By midseason the new car had only fleeting visits to circuits, usually with a DNS, or DNF listed as a result. By the end of June 1970 a report in Autosport seemed to begin to draw a veil over the Nomad project. Entirely self-funded, rising costs in international racing and at the behest of Konig’s bank manager, Mk3 was put up for sale, together with the reluctant release of his mechanic, Julian Pratt. The idea, at that stage, was for Konig to continue with the Mk2 Nomad as a privateer in selected races, i.e., Mugello and Vila Real. His comment to the publication at that time was, “It’s now a case for competing for fun instead of competing to win, but I hope Nomad 3 will be bought by someone who can campaign it like the competitive car it is.”

Photo: Bob Curl Archive

Records show the last period competitive race, on British soil, for Nomad Mk3 was on August 31, 1970, at Brands Hatch, Round 8 of the RAC Sports Car Championship. Lanfranchi was at the wheel, but the car failed to finish. Just one week later, Mark Konig also failed to finish at the Nürburgring 500. During the 1970 season, Paul Vestey had competed in various sports car races, in the main at the wheel of a Porsche 910, and over a handful of years he’d become part of that whole sports car racing “family” scene. In 1967, he’d raced a Ferrari 275 GTB, the latter part of 1967 and for 1968, he drove a Ferrari 250LM, in 1969 he’d raced a Chevron B8, a Ford GT40, a Chevron B6 and B8 and a Porsche 911. After talking to Mark Konig, Vestey suggested they compete in the Springbok and other races in South Africa during the winter months of 1970-’71. The races in Kyalami, Cape Town, Lourenço Marques, Bulawayo, Pietermaritzburg and Goldfields Raceway proved the racing pedigree of Mk3 had continued from the previous Nomads Mk1 and Mk2. Other than one DNF and a non-classification, Konig and Vestey picked up a 19th, 7th and 8th placings. Single-handed, Konig finished a very commendable 3rd place at the last race at Goldfields, on January 2, 1971, despite running without any coolant, the engine being comfortably air-cooled for two of the three hours to a secure a podium finish!

Nomad Mk3, like its two siblings, passed through a number of hands. It was purchased in the mid-late 1970s, together with Nomad Mk2, by John Piper, and raced under the name Stoic Racing. Bill Stephens raced one car and Piper the other. They competed mainly in national races and sprint meetings, by now both Nomads had lost their BRM power, which was replaced by a Ford V6. By the early 1980s, Piper sold both Nomads to Terry Davison. Mk3 was almost immediately up and running in hill-climbs, sprints and club races. Davison had nothing but trouble from the Ford engine and replaced it with a 3.2-liter 911 Porsche Carrera power unit. As much as he’d like to have had a two-liter V8 BRM, the £80,000 (cost in the mid-1980s) price tag put him off. So, Nomad went from V8 to V6 and then to flat-6. Crispin Manners, of Oak Tree Garage in Devon, UK, completed work for this transformation. Weber 46 IDA carburetors replaced the original fuel injection, and dyno tests showed the flat-6 engine produced 250 bhp, the same as the V8 BRM. The transmission was replaced too; the Hewland FT400 discarded in favor of a 5-speed Porsche Carrera transaxle unit with a very much modified gear linkage. Roger Dowson Engineering sorted out all the suspension settings and rear spring rate. Davison was left with a very competitive car. Indeed, it didn’t just look competitive, but won a number of HSCC Thundersports and Orwell Supersports Cup races and championships in the UK and Europe.

Driving Nomad Mk3

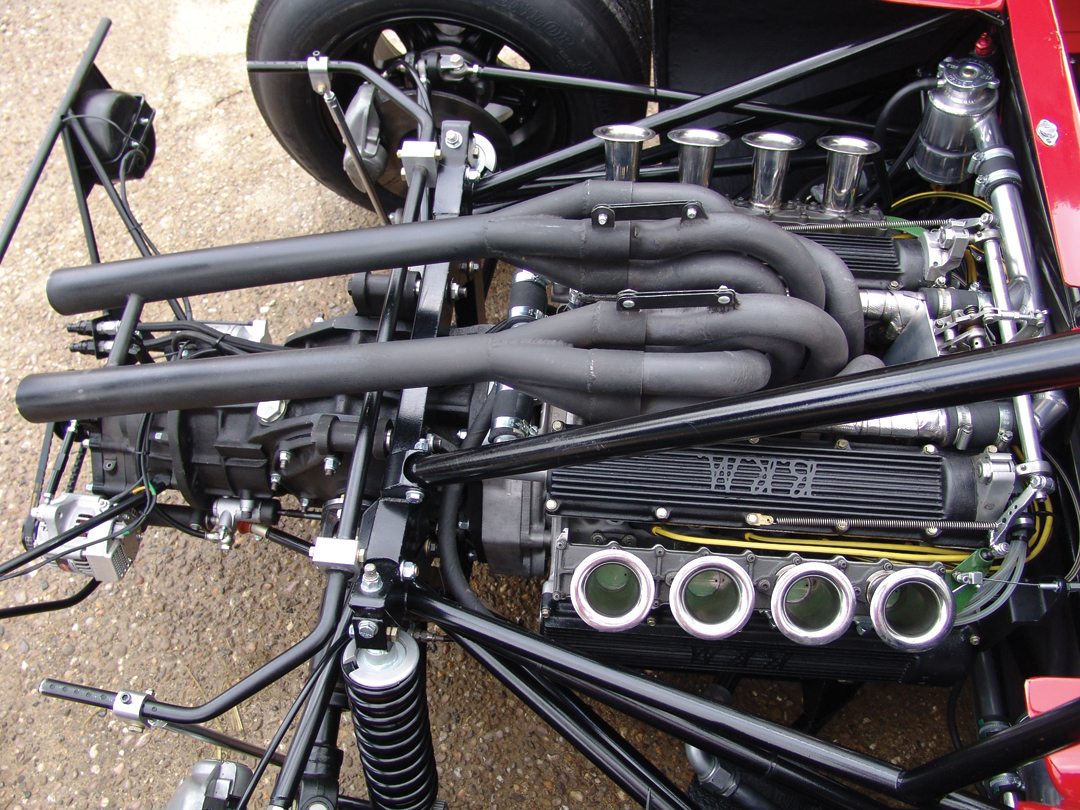

Following an excellent restoration project by Simon Ayliff at Neil Fowler Motorsport, Bourne, in true artisan fashion, the car is now ready for a shakedown run. It’s important at this juncture to mention names here, not something usually done in this space, but perfectly apt in this instance as both Ayliff and Fowler’s DNA are entrenched in motor racing, especially BRM as very close relatives of the two worked for British Racing Motors in period. This restorative work wasn’t just another job, but part of the rich tapestry of a significant marque’s racing history, albeit in a “foreign” chassis.

You could say the project became a labor of love. Substantial reconstruction was necessary to the frame as the original had to be radically altered, first to take the Ford V6 and then the more recent Porsche Carrera flat-6. Initial enquiries were made back to Bob Curl, the Nomad designer, and indeed Curl and Nomad mechanic Julian Pratt visited the Bourne works of Neil Fowler Motorsport very early in the restoration process. Some 18 months since that initial visit, and after many man-hours were put into the detail and final completion of the car, it’s now virtually back in its original state.

It is a late September day, and we’re giving the car its very first outing at a venue synonymous with BRM—Folkingham Aerodrome, or at least what remains of the place. Folkingham Aerodrome was opened in 1944 and closed in 1947. It was home to Troop Carrier Groups and involved in Operation Overlord and Operation Market Garden. Post-war BRM used the disused runways for track testing purposes. The Ministry took over the site again in 1958 and during the Cuban Crisis, Thor missiles were fueled ready to go within 15 minutes by November 1962. When the Ministry no longer needed the airbase, BRM once again used it as a testing ground for Grand Prix and sports cars. The demise of BRM was also the demise of Folkingham Aerodrome, the need for the large runways disappeared and the land was once again reclaimed for agricultural use. The concrete perimeter roads remain and we’ve been given permission to use these for testing Nomad Mk3.

The Autumn light and weather is a little hit and miss, the road surface is very wet in places and dry in others. Nomad Mk 3 stands purposeful and ready for action. It looks every inch the racer Bob Curl had envisaged almost 50 years ago. Sadly, in period it didn’t quite get the opportunity it deserved to prove itself, although racing car development and technologies were moving at quite a pace at that time. At that time, it was becoming very true, standing still lost a tremendous amount of impetus, but moving on cost a considerable sum of money. Climbing into the spacious cockpit, I say climbing, there is a door, but the car sits low to the ground, the driver sits comfortably aboard. Feeling for the pedals there is adequate provision—even a resting post for the rather idle left foot. The dash is adorned with the usual dials, the central and most important is the rev counter—the red line clearly visible. For the purpose of this test, the limit is 8,000 rpm, no more—the usual 10,000 rpm is strictly “out of bounds.” I’m told the engine has pedigree too; it is the same unit that took Graham Hill to victory on the streets of Monte Carlo way back in 1964. It was later increased in capacity and used in the Tasman series. Securely belted in, as the starter is pushed and the V8 roars, there’s a certain Mediterranean melody in the engine note, or perhaps, just my imagination running away with me?

We blip the throttle ensuring the already pre-warmed systems are fully up to running temperatures – 60°/oil and 85°/water. This is the first time since 1971 that the Nomad chassis and BRM V8 power have run in unison—quite a historic occasion, the long separation is at an end and a new beginning under way. The concrete road surfaces are a little greasy in places due to ambient conditions, the surface is not synonymous with any racetrack I’ve visited for many a year. In fact, it could be said, in places it’s reminiscent in quality to the streets of Sicily, home of the Targa Florio. With this in mind we prepare to move.

Immediately, I’m made aware of the very heavy steering as if a really heavy weight is impeding movement. Thankfully, it lightens a little with momentum. Thinking back to period racing, arms and elbows must have been completely shot post-race—especially at the many gruelling circuits visited. Again, thanks to the layout of today’s course we’re not testing the steering too much in full flight—just to turn around at the end of each run. Diametrically opposed to the steering, the gearshift is as light as a feather in comparison and moves with ease through the range. Having said that we haven’t used fifth so far, today is not about all-out power, simply a check that all systems are working correctly. There is no lap record, or FTD at this location; our only competition is from the occasional passing tractor, or at best Land Rover. The car holds the road well, very well balanced with no signs of over or understeer—the guys have done a fantastic job in setting it up with little, or no information. Period details are sketchy, power and drive changing from 46 years ago.

Conclusion

From this short and restrictive evaluation it is easily seen how this car was full of promise and anticipation. Mark Konig and Bob Curl were truly onto something good—if only. Throughout our racing, rallying and motorsport heritage there have always been those “if only” moments. If only a sponsor could have injected some cash, if only the major manufacturers hadn’t have developed so far in such a short space of time. There have been many teams past, present and possibly future that will suffer the same issues as the Nomad project. There are many stories to be told from those cars at the top of the motorsport tree. There are far more interesting stories from the “also rans” too—of sacrifice, ambition and pure “bloody mindedness.”

I’ll leave the words of Mark Konig as an epilogue to the Nomad: “While it was a lot of hard work and we didn’t win a whole lot of races, it was great fun. It was a very satisfying three or four years of my life. I think I pulled the plug at the right time. We were at the very tail end of an era where you didn’t have to have a research and development team behind you. Bob Curl did a wonderful job.”

SPECIFICATIONS

Engine: BRM P56 90° V8 1998cc

Gearbox: Hewland 5-speed manual

Brakes: Girling discs, all-round

Steering: Rack and pinion

Body: Fibreglass

Chassis: Steel tubular space-frame

Suspension: Front – double wishbones, coil springs over dampers, anti-roll bar. Rear – lower wishbones, top links, twin- trailing arms, coil springs over dampers

Weight: 637kgs / 1404lbs

Length: 3740mm / 147.24inches

Width: 1810mm / 71.26inches

Height: 1075mm / 42.32inches

Wheelbase: 2300mm / 90.55inches

Front track: 1450mm / 57.09inches

Rear track: 1465mm / 57.68inches

Front wheels: 475/10 x 16

Rear wheels: 600/12 x 15

Resources / Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Down the Hatch – The Life and fast Times of Tony Lanfranchi by Mark Khan

Specialist British Sports/Racing Cars of the Fifties & Sixties by Anthony Pritchard

Motor Racing Year 1967/1968/1969/1970 published by MRP

Periodicals

Autosport, Motor Sport, Motor Racing and Sportscar and Motor Racing

Thanks

Sincere thanks to Peter Wünsch for the use of his car, to Neil Fowler and Simon Ayliff Philip and the team at Neil Fowler Motorsport, Bourne. Special thanks to Mark Konig and Bob Curl for their factual input, kind assistance and patience in the production of this editorial. We’d also like to thank Clare and George Atkinson at Folkingham for use of their land and road.