Mercer Automobile Company was formed in 1909, a company distilled from the Walter Automobile Company and Roebling-Planche. Walter had been producing expensive high quality cars since 1902, and the Roeblings (the builders of the Brooklyn Bridge) wanted to produce a high quality and technologically advanced car as well. The new Mercer automobile was produced in Trenton, N.J., located in Mercer County.

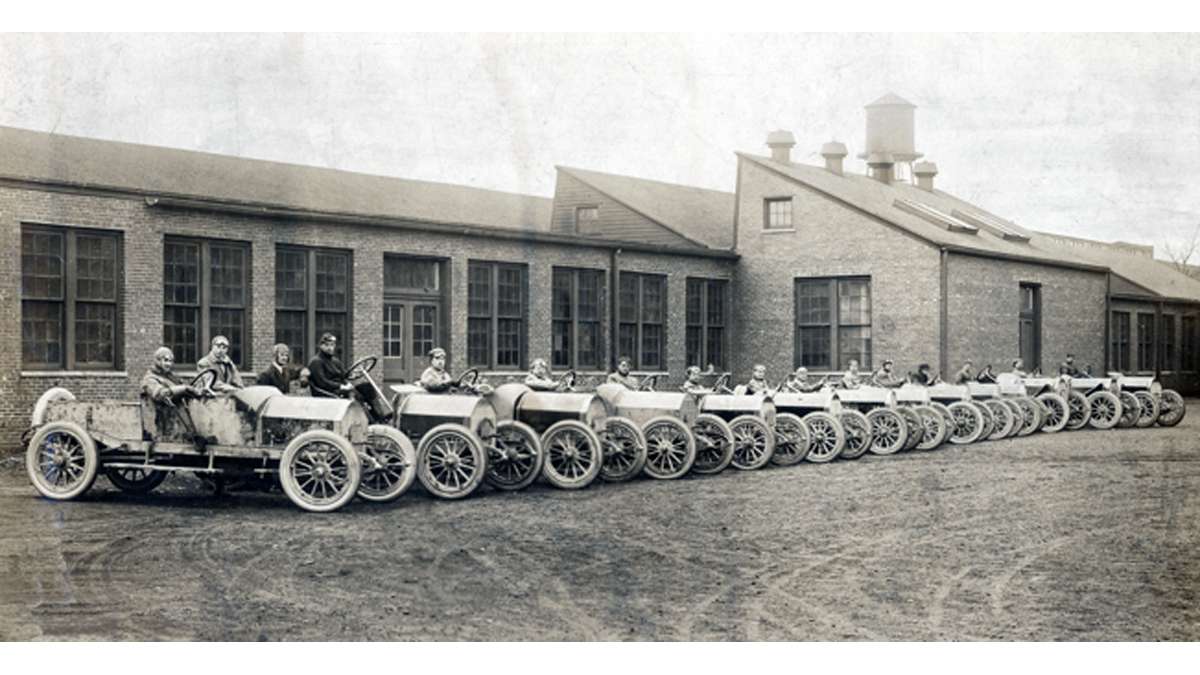

In 1911, the Type 35 Raceabout was introduced, and the Mercer legend began. Brilliantly designed by Finley Roberson Porter, the Type 35 Raceabout was ready for the road or the racetrack. Porter jettisoned all luxuries from the car not necessary for racing. It came with no roof, windshield, or body past the cowl. Other extremities, such as the fenders, lights, and running boards were designed to be quickly removed for racing. The car could be driven to the raceway and stripped down to just the radiator, hood, cowl, gas tank two bucket seats and a small tool box.

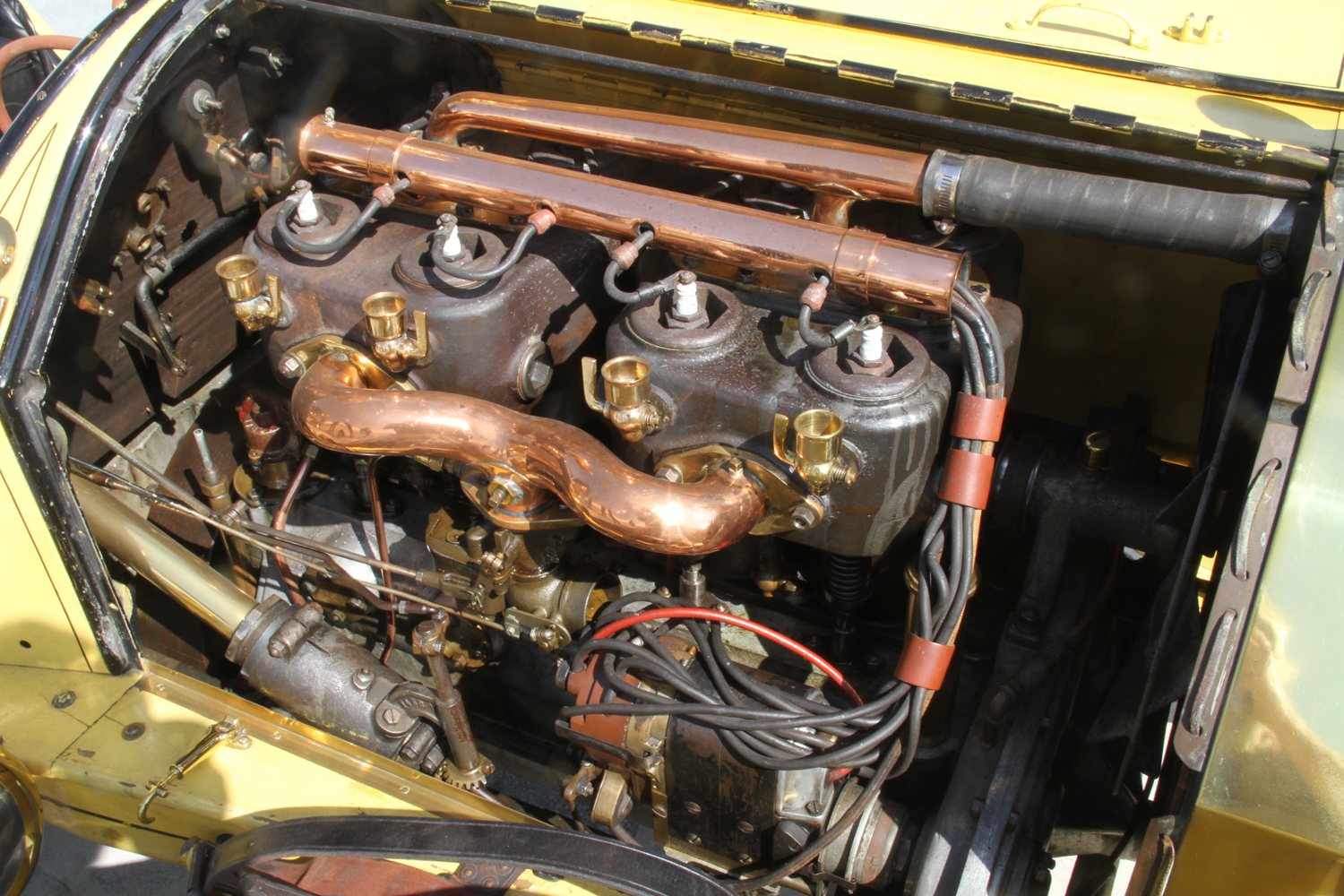

This car was built for speed, but it did not have a large engine. Most high-performance engines of the day were quite large in displacement, some as large as 600-cubic inches, even with only four or six cylinders, but the Mercer’s engine was only 307-cu.in. Porter’s quest for performance carried through to the Mercer’s high-compression T-head engine design that featured a two-spark Bosch magneto firing two plugs per cylinder. Fuel delivery was from a single bronze Fletcher updraft carburetor with an auxiliary air valve and a second jet feeding in more fuel above 800 rpm. The engine’s horsepower rating is somewhat debatable, perhaps as low as 30 horsepower, depending on the source. George Wingard wrote in his book Wolves in Sheep’s Clothing that Mercer engines “would dyno out at 60 hp at 1,900 RPM or it was not allowed to leave the factory.”

David Greenlees, publisher of the The Old Motor, a respected pre-war car focused website, noted brass-era restorer and Mercer expert confirms that the cars left the factory as tested at 60 hp. T-Head Mercers where made from 1911 to 1914. The 1911 and 1912 models had 3-speed transmissions. A 4-speed transmission was utilized for 1913 and 1914 models, allowing the car to achieve speeds up to 100 mph. A rear differential was used as opposed to chain drive system. The Mercer also had a lower ride height than most of its contemporaries. The light weight design (around 2500 pounds) and lower center of gravity made the Mercer a superior handling machine.

It is as true today as it was a hundred years ago: speed and handling are the two most important criteria when selecting a racecar. Mercer was the choice for many racecar drivers of the day, including Barney Oldfield, Hughie Hughes, Ralph DePalma, and Washington Roebling II. Sadly, Washington Roebling II perished on the Titanic in 1912. The Mercer was a formidable racecar, racking up an impressive number of documented wins by professionals, and many other victories in amateur events that went unrecorded.

DePalma set records in May 1912 with a Mercer, driving a Raceabout “150.506 miles in 130 minutes 43 seconds, an average of 69.54 miles per hour -on a road course” wrote Ken W. Purdy about DePalma’s exploits behind the wheel of a Raceabout in his 1949 book Kings of the Road. He goes on to report, “The next day he took the same car to Los Angeles and hung up track records for one mile, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 15 and 20. Averages in the high 60’s and 70’s over all kinds of courses at distances up to 500 miles were often made by the Mercer, averages that would not be easy to duplicate today despite all that has been learned about fast motoring in the almost 40 years that have past.”

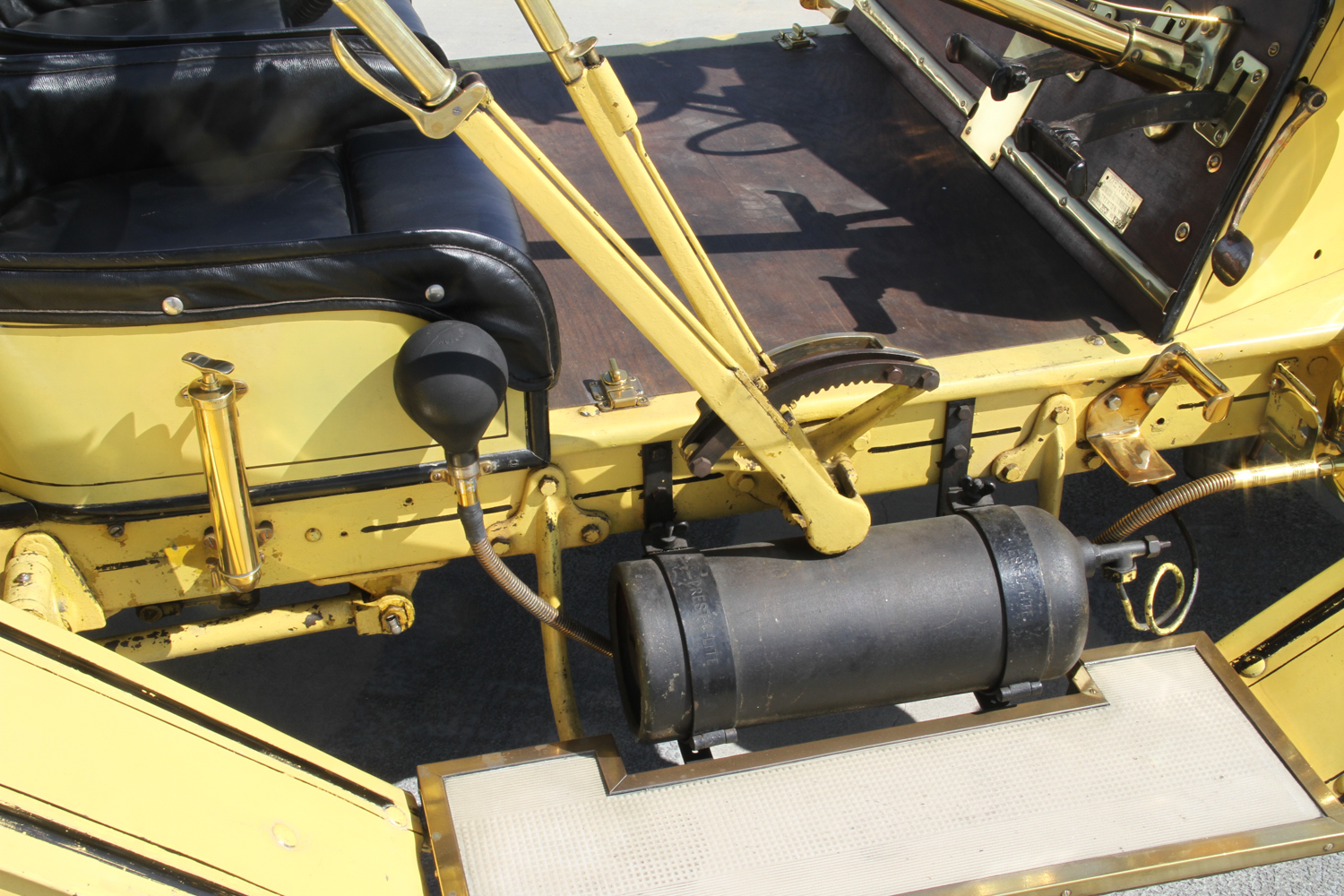

The experience of riding in one of these rare and wonderful machines is truly unique. I had the privilege of being passenger in a 1914 Raceabout, one that was devoid of fenders and headlights, ready to race. Although thrilled at the chance to ride in such an important and historically significant automobile, I was in no way prepared for the sheer power and acceleration it possessed. The raspy sound of the mighty T-headed engine was absolute music to my ears as we blasted down the road, and the road is always in view. As we quickly gained speed the yellow lines of the road start to blur as I looked down at my left foot, which was resting outside the body of the car in a thoughtfully placed brass footrest. (The Mercer Raceabout was a right-hand drive car).

Of course a windshield, safety belt, or even a grab-bar would have been considered pampering. The driver was busy with the task at hand: Taming the beast. His hands and feet were constantly conducting a symphony of switches and levers, while I clung on to the side of the little metal bucket seat and enjoyed the ride. The thought of hurling down a dirt road in such a machine 100 years ago on skinny tube tires and wood-spoke wheels is humbling. I can just imagine what it was like then, when most cars were maxed out at 35 to 40 mph, to see a Mercer scream by at over 70 mph, dodging horses, people, bicycles, large pot-holes and ruts on country roads, or running neck and neck with other racecars barely under control around a track lined with spectators.

The most recognizably similar car of the era is the Stuz Bearcat. The Bearcats produced from 1912 to 1916 also had the stripped-down, no doors look that personifies the brass-era sports car. There were other fast cars, mostly of much larger cubic-inch and monstrous proportions such as the National and the Simplex, but the Bearcat is the most remembered. The Stuz Bearcat was heavier, had a larger engine, and would eventually collect more track victories, however Mercer aficionados are quick to point out that the Bearcat was produced for a longer period of time. The Mercer-Stuz rivalry has been getting collectors and automotive historians’ knickers in a twist for over 100 years. The argument was alive and well according to Ken W. Purdy, even in 1952.

Purdy was partial to the Mercer Raceabout, and documented his experience in the late 1940’s when he located and restored one for his own pleasure. Purdy’s chapter on the Mercer in Kings of the Road certainly let his opinion be known, at first fairly objectively stating, “The Stuz was a wonderful car, and as a racer it may take pride of place by reason of the fact that Stutzes were still running in competition in 1929, by which time Mercer had given up the ghost. But in the years 1911-1915, when a ding-dong battle between the two makes enlivened nearly every major American road and track event, the struggle was fairly even. Brutal objectivity might give the decision, by the width of a hair, to the Stuz, on the ground of most races won. But the Mercer had the smaller engine of the two, and if the results were weighted on that basis, the Mercer would come out ahead.”

But on the next page, Purdy takes his driving gloves off, and really lets us know what he thinks in no uncertain terms: “In my own view, the early ‘Bearcat’ is a gaunt and ugly piece of machinery when laid alongside a Mercer Raceabout for comparison. It is high and heavy in profile, badly misses the lithe look of the Mercer.” Then he defiantly proclaims, “Anyone who suggests that I am prejudiced is right. I am. I think the Mercer is a better car: better in design, better in basic material, and infinitely better esthetically.”

Both shockingly opinionated and comical, Mr. Purdy’s comments from over 75 years ago only add to the Mercer legend and mystique. The point here is that these cars have been cherished since new. Built in low numbers (sources say about 150 per year), they have always been worth a good deal of money. A new Mercer cost around $2,500 in 1911, when the average American income was $75 year. The Mercer Associates, an organization formed by enthusiasts of Mercer Automobile was formed back in the late 1940s. Today, the T-head Mercer Raceabout is among the most coveted and valuable cars from the brass era. A well preserved 1911 Type 35-R Raceabout sold for $2,500,000 at the 2014 RM Auction in Monterey, proving once again how revered these cars are still.

Many consider the Petersen Museum’s 1911 Type 35-J Mercer Raceabout to be one of the most original and well preserved examples in existence. This Mercer was sold new to Mr. and Mrs. John F. Gray, by the Whiting Motor Company in New York. It stayed in the Gray family for over 30 years. The car was then sold and brought to the West Coast where it was driven around the Del Mar area until World War II when it was parked.

Many early cars were sold for scrap during the war, but fortunately the owner just donated the tires, and not the car to the war effort. Many other rare and interesting cars were not so lucky. In 1943, collector Herbert Royston purchased the car, keeping it until the mid-1970s. Legendary racecar driver Phil Hill purchased the car next. Robert Petersen, in turn, purchased the car in 1999 at auction from Christie’s, and it has remained in the Petersen collection since then.

The car is exceptionally original, and according to the Museum, was painted just once in the 1940s. The yellow color is closely associated with Mercer Raceabouts, just as the color red is with Ferrari. The car appears to not have a race history, perhaps accounting for its well-preserved, unrestored condition. A period accessory on the car is a monocle windshield, and it sports a single acetylene spotlight mounted on the top of the dash board. The museum does exercise the car, taking it to local shows and concours events, most notable being the 2013 Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance where Mercer was one of the featured marques that year. It also participated in the Pebble Beach Tour d’Elegance that same week. Peterson Museum curator Lesile Kendall is confident in the car’s performance and reliability saying, “I would have no qualms about driving this car cross country as it sits now.”