Over the course of nearly seven decades of Formula One history, only three men have ever won a World Championship Grand Prix race in a car of their own construction. Of course, none of them actually designed or built their cars all by themselves, they simply conceived, established, directed, managed and contributed to the organizations that did.

They shared an affinity for precision, exploration and invention. Their active, inquisitive minds made them resourceful and drove them to succeed. They raced in the days when Formula One was more of a family gathering—a veritable band of gypsies assembling at and dispersing from sites around the globe on a regular basis—than the corporate environment in place today. That meant they could also be friends—as well as, we shall see, teammates—but they were first and always rivals. In those days F1 had not yet become every driver’s sole focus, so their worlds intersected on multiple levels beyond sharing their singular achievement.

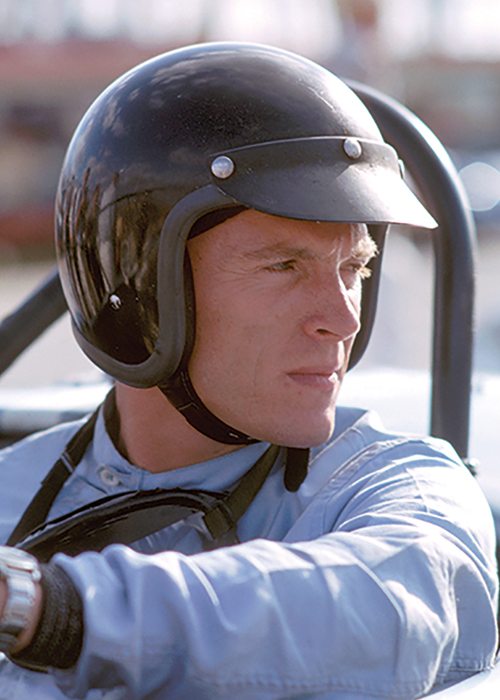

The individuals in question are, of course, Jack Brabham, Dan Gurney and Bruce McLaren, and they stand alone together atop the sport’s pyramid of accomplishment.

Three decidedly different men who shared the same mission

Photo: Roger Dixon

Jack Brabham served as a flight mechanic with the Royal Australian Air Force during WWII, and upon returning home ran a small engineering shop. He began to race midget cars in 1948, and success in those led him to look further afield. He made his Formula One debut driving a Bristol-engined, envelope-bodied Cooper T40 in the 1955 British Grand Prix at Aintree—where homeboy Stirling Moss led a 1-2-3-4 Mercedes-Benz W196 sweep ahead of Juan Manuel Fangio, Karl Kling and Piero Taruffi. The next year Brabham’s sole GP was again the British, where he entered himself in a Maserati 250F, and for ’57 he drove a rear-engined Cooper T43-Climax in five GPs, but scored no points. For 1958, he was installed behind the wheel of a factory Cooper T45-Climax from Monaco onward, validating his selection by scoring points on three occasions.

Established as team leader at the Surbiton-based team for 1959, Brabham became Australia’s first F1 winner by driving a Cooper T51 to victory at Monaco, then added a second win at Aintree in July on the way to his first World Championship—the first ever to be won in a rear-engined car, or by an Australian. In the season finale, the inaugural United States Grand Prix at Sebring, he sealed his championship by pushing his fuel-less car across the finish line in 4th place as his teammate and protégé, a promising New Zealander named Bruce McLaren, became the youngest driver ever to win a Grand Prix.

Brabham repeated as World Champion in 1960 with wins at Zandvoort, Spa, Reims, Silverstone and Oporto, then suffered through a winless and largely unproductive 1961 season whose primary highlight was a stunning 9th-place finish in the Indianapolis 500 aboard an underpowered though over-bored F1 Cooper. That performance reshaped the face of America’s premier race by catalyzing the rear-engined revolution in Indycar racing, just as Cooper had done in F1. Brabham left Cooper at year’s end, however, to set up his own Brabham Racing Organisation.

Photo: Roger Dixon

Bruce McLaren first raced with an Austin 7 Ulster that he had built and prepared himself as a pre-license teenager. He progressed quickly and soon became the first recipient of New Zealand’s “Driver to Europe” scholarship, earning it with a couple of stellar performances in the New Zealand Grand Prix, the first in a Cooper-Climax sports car acquired from his mentor Brabham, the second in a works Cooper Formula Two ride he got with Jack’s recommendation. He made his F1 debut at the Nürburgring’s German Grand Prix in 1958, finishing a superb 5th behind the wheel of a Formula Two Cooper T45.

McLaren joined the Cooper operation full-time to partner Brabham for the 1959 F1 season, paying back the team’s faith with his surprise victory in the season finale at Sebring’s inaugural United States Grand Prix. By doing so, he became not only F1’s youngest winner, but its first Kiwi victor as well. He made it two in a row by winning the 1960 season opener in Buenos Aires after Brabham dropped out, then ably supported his teammate with a run of other podium finishes to take 2nd in the final point standings as Jack reeled off five midseason wins in succession to repeat as World Champion. When Ferrari dominated the 1961 season with its shark-nosed 156, McLaren ended up in a tie with Jim Clark for 7th in the points, while Jack settled for equal 11th with John Surtees. The process for Brabham’s creation of his own team had, however, already been set in motion.

Bruce carried on with Cooper through the next four seasons, winning Monaco and taking four other podium finishes to claim 3rd in the championship for 1962. Cooper, however, ultimately lost competitiveness, leaving McLaren with little alternative but to go the same route as Brabham, expanding the Bruce McLaren Motor Racing team he’d started up three years before to tackle Formula One’s landmark 1966 season.

Photo: Arte House

Dan Gurney rode the buzz from serial sports car success in America into a test with Ferrari that earned him four Grand Prix starts with the Scuderia in 1959. He qualified on the front row and finished 2nd at the Nürburgring, then took 3rd in Portugal to kick off his GP career in fine style. An unproductive year at BRM in 1960 was followed by two seasons at Porsche, where he finished 3rd in the 1961 championship and then registered his own first GP win at Reims—the Porsche marque’s sole F1 success—in ’62 before signing on as Brabham’s teammate.

Seated in the brand-new Brabham BT7 for the ’63 F1 opener at Monaco, he endured the first of a run of mechanical failures that would blight half of his races during that first season with the Australian’s team. When he did finish, it was almost always in the points—thrice on the podium—and the following year in France he recorded Brabham’s first win as a constructor, adding victory in Mexico’s season finale as well.

By then, however, the creation of All American Racers was already under way back in California, so the 1965 season had a touch of “lame duck” feeling to it even though he closed the year with five consecutive podiums. Brabham seemed to know what he was losing.

“Jack was unhappy when I told him of my plans to build our own American F1 car and have my own team,” Gurney reflected recently. “He had planned to retire and leave the team in the hands of myself and Denis Hulme. My plans to leave—though he understood—threw a monkey wrench into his plans, and he had to go on driving because Denny was a relative F1 newcomer and Jack felt he needed an experienced driver to lead the team.

“As history shows, it turned out very well for Jack, as he won his third World Championship title with his own car. All three of us stayed friends, and Jack often reminded me in later years that had I stayed with him I would have been World Champion. But such is life in the fast lane.”

Building Brabham

As Jack Brabham worked to establish his own operation, he brought in his old mate, Ron Tauranac from back home, to design the cars and the two meshed well as a pair of practical, no-nonsense guys on a mission. Their philosophy was to produce simple cars that were easy to operate, so they set up their English base in New Haw, along the banks of the River Wey in Byfleet, and began cranking out “easy to drive, progressive-handling racing cars,” according to Alan Henry, author of Brabham: The Grand Prix Cars. To do this they decided to stay with simple spaceframe chassis construction as opposed to trying the latest monocoque technique as pioneered by Lotus.

The plan worked very well as F1 transitioned from 1.5-liter engines to 3.0-liter power because, while other teams scrambled to develop new 3-liter power plants, Brabham continued his conservative approach, relying on a single-overhead camshaft V8 from the Australian firm Repco that had been derived from an abandoned General Motors aluminum block engine originally used in the Oldsmobile F85.

It proved to be the way to go as the Repcos provided excellent reliability, and in 1966 Brabham won four World Championship rounds and two non-points races with the BT19 while failing to finish only twice, neither retirement due to engine failure. As a result, Brabham became not only the first man ever to win a Grand Prix in a car of his own construction, but the only driver ever to win the World Championship itself in those circumstances as well. And, of course, his team also claimed the Constructors Championship.

The following year, Gurney’s replacement, Hulme, stepped up and won a pair of GPs and scored six other podium finishes with a BT20 on his way to securing the 1967 World Championship for himself, and another constructors crown for the team as Brabham finished 2nd in the points. Jack was not only the first to win in his own car but, as the most accomplished, mentored both McLaren and Gurney—as well as Denis Hulme.

Not being bound solely to Formula One, Brabham—through Motor Racing Developments—became the world’s largest manufacturer of customer racecars during the 1960s, building cars for Formula Junior, Sports Racing, Formula Two, Formula Three, Indianapolis, Formula Libre, Formula B, the Tasman Series, Formula Atlantic and Formula 5000, as well as F1. Upon retiring from F1 after the 1970 season, Brabham sold his half of the company to Tauranac, and it wasn’t long before the concern passed into the hands of one Bernard Charles Ecclestone.

Flying the Eagle

The seeds for Dan Gurney’s Eagle F1 project were sown at Indianapolis in May of 1964 when Goodyear, trying to challenge rival Firestone’s longstanding tire monopoly in the annual 500-mile race, instead got its lunch handed to it as all its intended runners—including eventual winner A.J. Foyt—switched to Firestone rubber right before the race.

Stung by the defections, Goodyear wanted to ensure a repeat would not be possible by enlisting one of its distributors, Carroll Shelby, to build Indycars exclusively for Goodyear teams. Shelby, however, allowed as how he had too much on his plate already—since he was building Cobras and running Ford’s burgeoning Le Mans program—and suggested the project should go to Gurney. Ultimately the two men formed a partnership and All American Racers was born, funded by Goodyear.

Although the tiremaker’s focus was on Indianapolis, Gurney, as his part of the bargain, craftily convinced the company to provide a budget for an Eagle F1 effort as well. Because the rules for F1 and Indycars were, at that moment in time, fairly similar, this could be accomplished with what was effectively one chassis design, upon which the variances could be installed. Len Terry, fresh from designing the Indy-winning Lotus 38 for Colin Chapman, was hired to draw the new car(s), and produced what many feel is the most beautiful Grand Prix car ever.

Photo: Roger Dixon

Since F1 was changing its formula, this was the perfect time for new teams to jump in, and Gurney commissioned a bespoke 3-liter V12 engine from England’s Weslake Engineering to power the new Eagle—named for his homeland’s national symbol rather than himself.

When the new engine was not ready for the start of the ’66 season, however, he was forced to use the venerable 2.75-liter Coventry Climax FPF four-cylinder to power AAR’s first five GPs.

The V12-powered Eagle finally debuted at Monza in September, but while drawing raves for its compact design, internally the engine remained a work in progress. It finally came right at the Daily Mail’s non-points Race of Champions at Brands Hatch in March of 1967 where Gurney won both heats to register the F1 Eagle’s first success. Three months later he would stand atop the podium at Spa in Belgium, after winning a proper Grand Prix, and join Brabham as the only men to be Grand Prix victors in their own cars.

Where Brabham had gone conservative, sticking with the tried and true, Dan stood right out on the cutting edge, not only with Harry Weslake’s V12, but ultimately with a monocoque chassis, numbered 104, uniquely constructed primarily of titanium and magnesium rather than aluminum. Sadly, Gurney’s F1 dream eventually faded away along with AAR’s budget as Goodyear allocated its funding elsewhere.

AAR carried on building Eagle Indycars, then subsequently branched out into Formula 5000, Formula Ford and Grand Touring Prototypes, building championship-winning cars for all and winning three Indy 500s.

Making McLaren

Bruce McLaren had founded his eponymous motor racing organization in 1963—while still at Cooper—and the following year built the first racecar to be badged as a McLaren, the tube-framed M1A, to Group 7 rules. In 1965 there came an experimental prototype single-seater, the M2A, designed by Robin Herd as a monocoque chassis powered by a pushrod Oldsmobile V8.

Photo: Roger Dixon

With the dawn of F1’s three-liter era in 1966, the first McLaren Grand Prix car, the monocoque M2B, appeared, initially powered by a downsized Ford Indy V8 that was subsequently replaced with a Serenissima V8, although neither engine was well suited for the task. For 1967, McLaren fielded an interim M4B Formula Two chassis with a two-liter BRM V8 for two early GPs, but it was not competitive. Taking a midseason hiatus while awaiting completion of the first BRM V12-powered M5A, Bruce took over the second of Gurney’s Eagle-Weslake entries, replacing the suddenly retiring Richie Ginther for the French, British and German GPs. McLaren qualified the Eagle 5th in both France and Germany and 10th in England, but was let down by engine-related problems in all three races.

Although a variety of difficulties more or less derailed the Robin Herd-designed M5A, it was a proper Grand Prix chassis and led directly to the Ford Cosworth DFV-powered M7A that appeared for 1968. The M5A did enjoy one last outing in ’68 as the team’s new signing, Denis Hulme, finished 5th in the season-opening South African GP while McLaren stayed behind at the base to finish up the M7A.

Bruce gave the new car a fine debut by winning the non-championship Daily Mail Race of Champions at Brands Hatch, which Hulme followed up five weeks later with another points-free victory in the Daily Express International Trophy contest at Silverstone. Once the championship season resumed, it took McLaren four races before he registered a fortuitous victory at Spa to join Brabham and Gurney in their exclusive club.

Although McLaren himself did not manage to win another Grand Prix in the two years before his untimely death while testing at Goodwood, teammate Hulme won two more GPs in 1968 and added a third in ’69. Then, with his friend and team leader gone, posted another three wins before retiring after the 1974 season. The team, as we know, went on to become the second most successful operation in F1 history behind only Ferrari, raking in some 182 wins, a dozen driver’s titles and eight constructors crowns to date.

Like Brabhams and Eagles, McLarens also raced successfully beyond F1, most notably in the Can-Am and Indycars—winning three Indy 500s—but also Formula Two and Formula 5000. In more modern times, the company has fulfilled one of Bruce’s dreams by establishing itself as a builder of high-performance road cars.

Expanding the Bonds

Continuing connections abound among our trio, of course, as McLaren and Gurney were both part of the Ford Le Mans effort. Bruce scored Ford’s first triumph there in 1966—along with compatriot Chris Amon—after Dan had taken pole with the GT40 Mark II he shared with Jerry Grant and later led for many hours before a leaking radiator removed the red car from the intramural battle for the lead.

In the fall of 1966, when Gurney scored Ford’s sole Can-Am win with the AAR Lola T70 at Bridgehampton, he was chased home by a pair of McLaren M1B-Chevrolets driven by Amon and McLaren, and before Dan triumphed at La Sarthe with his compatriot, A.J. Foyt, in the Ford Mark IV the following June, Bruce had won the 12 Hours of Sebring earlier that Spring in a Mark IV he shared with Mario Andretti. Both men also provided Ford with valuable engineering input beyond their cockpit commitments.

In 1968, with the Eagle F1 project closing down, Dan arranged to race a third McLaren M7A-Ford in the season-closing trio of North American GPs. After being stopped by a rock through his radiator at St. Jovite, he earned 4th–place points behind Jackie Stewart’s Matra, Graham Hill’s Lotus and John Surtees’ Honda at Watkins Glen, but then retired with suspension issues in Mexico City after qualifying 5th.

The following September, with Gurney enduring a problematic switch to big-block Chevrolet power in AAR’s modified McLaren “McLeagle” Can-Am entry, at the Michigan International Speedway round of the championship McLaren offered him his team’s spare M8B for the race. Dan proceeded to carve his way up from the back of the grid to join Bruce and Denny on the podium. Earlier in the weekend, Brabham had tested the same car, but decided to stick with his original experimental Ford entry instead.

Then, in the dreadful aftermath of Bruce’s tragic testing crash at Goodwood in the Spring of 1970, Dan stepped in to provide an emotional anchor and help hold the team together. Hulme had severely burned his hands at Indianapolis and was less than his best, so Gurney forged the M8D to victory in the Can-Am season’s opening two rounds before a contractual dispute—he was sponsored by Castrol, McLaren backed by Gulf—spoiled his best opportunity for a Can-Am championship.

Before that commercial debacle, however, Gurney had also made his final three F1 starts in Bruce’s M14A-Ford, dropping out of both the Dutch and British GPs with mechanical ills, but scoring the final point of his F1 career with a 6th–place finish in the French Grand Prix at Clermont-Ferrand.

So, what bound these three extraordinary men so closely together?

“The common bond,” says Gurney now, “was an intense curiosity and interest regarding vehicle engineering. It was an era where building your own car was a possibility. Bruce and Jack were both graduates of Cooper, and they were open and adventuresome. I studied and learned by driving a great variety of cars and driving for many different teams on the sports car, F1 and Indy circuits. When Cooper broke off from the norm and started the mid-engine car revolution, Jack and Bruce were both there at the right time.

“I was there a little bit later. Everyone had a Hewland gearbox and a Coventry-Climax engine, and everybody was trying to reach for something that would give them bragging rights. We all liked a challenge and we knew all the sources we had were up to speed on the technology. The opportunity was there and we took it. We enjoyed exploring the unknown.

“In terms of geography, we traveled around the world at a time when that was logistically often an adventure. Sometimes it was just across The Channel, other times it was going to South Africa or Argentina in airplanes that did not have the safety record they have today. We also had great physical and mental fortitude in order to keep going and to press on when things were tough and difficult—especially in regard to the racing accidents and tragedies in that era.”

It was easy, Gurney says, to feel a kindred spirit with Jack and Bruce. “Our goals were similar, we wanted to build our own Formula One cars and represent our countries on the international stage. Bruce was a big thinker; he was planning to build road cars and everything. After Jack won three World Championships he retired, yet later he was looking into some pretty wild internal combustion engine schemes.”

Dan’s post-driving career activities have included managing successful AAR efforts in multiple series, the growth of AAR into an engineering powerhouse and the development of his beloved Alligator motorcycle concept.

So it was that these three men wrote their own chapters of racing history, often using the same pen. Gurney sums up their shared accomplishment succinctly: “Those were great times and those were great pioneers. We all wanted to do something that stood out on the international stage, and there it was.”

The Bear in the Works

Although he confined himself to driving and didn’t venture into car construction, Denis Hulme is deeply involved with our trio of legends, having driven with and for all three.

The likeable Kiwi broke into F1 with Brabham’s team as Gurney’s heir apparent in 1965, contesting all but one of the European F1 rounds, finishing 4th in France and 5th in Holland, then after ably supporting Jack in ’66, won his own World Championship with the team in ’67. That same year he signed to drive for McLaren in the Can-Am, which ultimately led to him moving over to partner McLaren in F1 as well for ’68. As the “Bruce and Denny Show” ruled the Can-Am, Hulme was crowned series champion in 1968 and 1970, and won more than twice as many Can-Am races as anyone else.

In ’67 he’d also turned up as a rookie at Indianapolis, driving one of Gurney’s Eagles for independent entrant Smokey Yunick and guiding it to a fine 4th–place finish that earned him Rookie of the Year honors. He repeated that result the following year with a works Eagle as Dan’s teammate, and contested the ’69 500 for AAR as well, but retired at three-quarter distance with clutch failure.

Hulme carried on as F1 team leader at McLaren until his retirement following the 1974 season, by which time Emerson Fittipaldi had arrived and collected the team’s first World Championship. At that year’s season opener in Argentina, though, the victory went to the McLaren M23-Ford driven by none other than Denis Hulme. Good to the last drop.

The Fourth Face

Were the three men from our main story to be enshrined in a suitable monument, say a mountainside rock carving like America’s Mount Rushmore, it might be wise to compete the package by including a fourth face. That would be a likeness of John Surtees CBE, the 1964 World Champion, who later became a constructor and drove a Surtees TS9-Cosworth to victory in the non-championship Gold Cup race at Oulton Park in August of 1971.

Surtees had switched to F1 following his multiple World Championship motorcycle racing career, driving first for Lotus, then Cooper and Lola before joining Ferrari for 1963 and winning the following year’s World Championship for the Scuderia. After being abandoned by the Italians he bounced back to Cooper, then to Honda and BRM before establishing the F1 branch of Team Surtees at mid-season in 1970, with TS7-Fords for himself and Derek Bell. Both drivers scored debut season points for the marque as John ran 5th in Canada and Derek took 6th at the USGP.

For 1971, essentially John’s last season—though he did race at Monza in ’72—he bagged World Championship points with a 5th in Holland and a 6th in the British GP prior to his Oulton Park success. He was partnered that year by Rolf Stommelen and Mike Hailwood, both of whom also scored championship points, then in 1972 Hailwood (the ’72 F2 champ in a Surtees TS10-Cosworth) recorded the marque’s best points-scoring result ever with a 2nd–place finish at Monza.

The team carried on for six more seasons before John closed the doors, but never really matched the results of the earlier years.