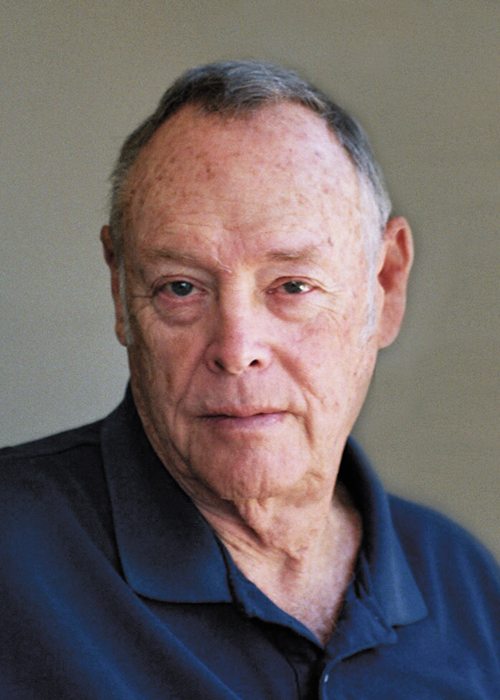

A short time ago, while looking for a photograph, I came across a negative of Miles I had never printed. So I made an 8×10 and I gave it to Carroll Shelby. Shel told me that not a day goes by that he doesn’t think about Ken. Perhaps more than anyone else, Miles was responsible for the success of the Cobra and Shelby’s sixties-era racing program. As a matter of fact, a Cobra never won a race until Ken joined Shelby’s team. Miles was not only a great race driver, but also a very talented designer and mechanic.

I feel fortunate to have been able to count Ken as a friend, not just for me personally, but also my family. My dad and Ken became best friends as did my stepmother and Ken’s wife, Mollie. Their son, Peter, was a companion and playmate for my younger siblings.

Even though Ken died more than 40 years ago, I thought it might be interesting for my readers to take a look, not just at Ken’s many accomplishments, but also at his significance for our sport. He made a huge impact on U.S. road racing during the fifties and sixties. Although his wins for Shelby are perhaps well known to most aficionados, his other endeavors deserve as much recognition.

Ken burst on the West Coast scene in 1954 by winning every single race he entered—including the Pebble Beach Cup—driving a car he, himself, designed and built, the famous MG Special R-1. The following year, he was elected president of the California Sports Car Club. In those days, the Cal Club, as it’s called, was dominant in organizing road races in Southern California, then the hotbed of the car-crazy culture. During the fifties, he served two additional terms as president and was always on the board. Much of the time, the Cal Club staged a race virtually every month. More than anyone else, Miles was responsible for establishing temporary courses and setting the schedule. He believed that the more seat time drivers got, the better and safer the racing.

Ken, along with Sam Hanks and Rodger Ward, were instructors in perhaps the first road-racing school. The Road Racing Training Association—located in Southern California—started in 1955. I described it in my February 2011 column. Ken frequently helped me with my own attempts behind the wheel.

In addition to other activities, Ken laid out courses on airports and parking lots. In one case however, he actually designed a real road course from scratch. It was Paramount Ranch, undoubtedly one of the then most demanding circuits in the U.S. The Ranch is in a hilly section of the Santa Monica Mountains, just north of Los Angeles. My friend, Dick Van Laanen, was with Ken when he laid it out. “With me riding shotgun, Ken flogged his VW all over the place, crashing and bouncing around through the bushes.” There were seven races there in 1956 and 1957 as well as a few practice weekends. Although challenging, it was my favorite course.

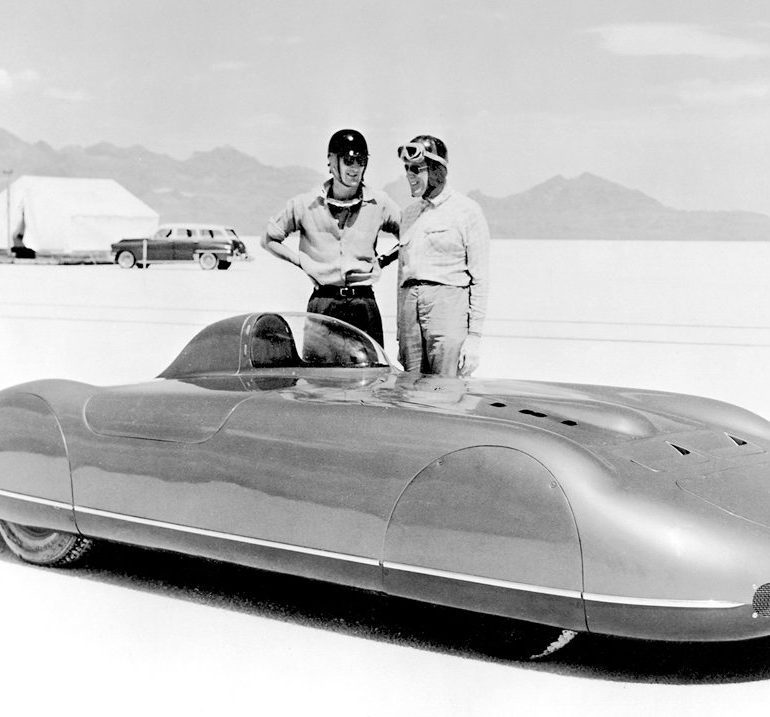

An aspect of Ken’s career often forgotten was his signal achievement at Bonneville in 1956. Miles and George Eyston set a number of records at the Salt Flats in an experimental MG. The two, taking three-hour turns, ran for six hours at 121.53 mph for 12 hours at 120.87 mph, setting new American records. A new international record was set for 12 hours from a standing start with an average speed of 120.74 mph. The previous year, Miles and Johnny Lockett were 12th overall and 5th in class at Le Mans in an MG.

Although he would have to be classified as a professional race driver, Ken never made it his career. He always had a job of one sort or another. When he came to the U.S. in 1951, he worked for MG distributor Gough Industries until 1955. Afterward, he was a car salesman for a number of dealers until he opened his own shop in 1960. (In 1959, he sold me a used Porsche Speedster that I drove for transportation, but never raced.)

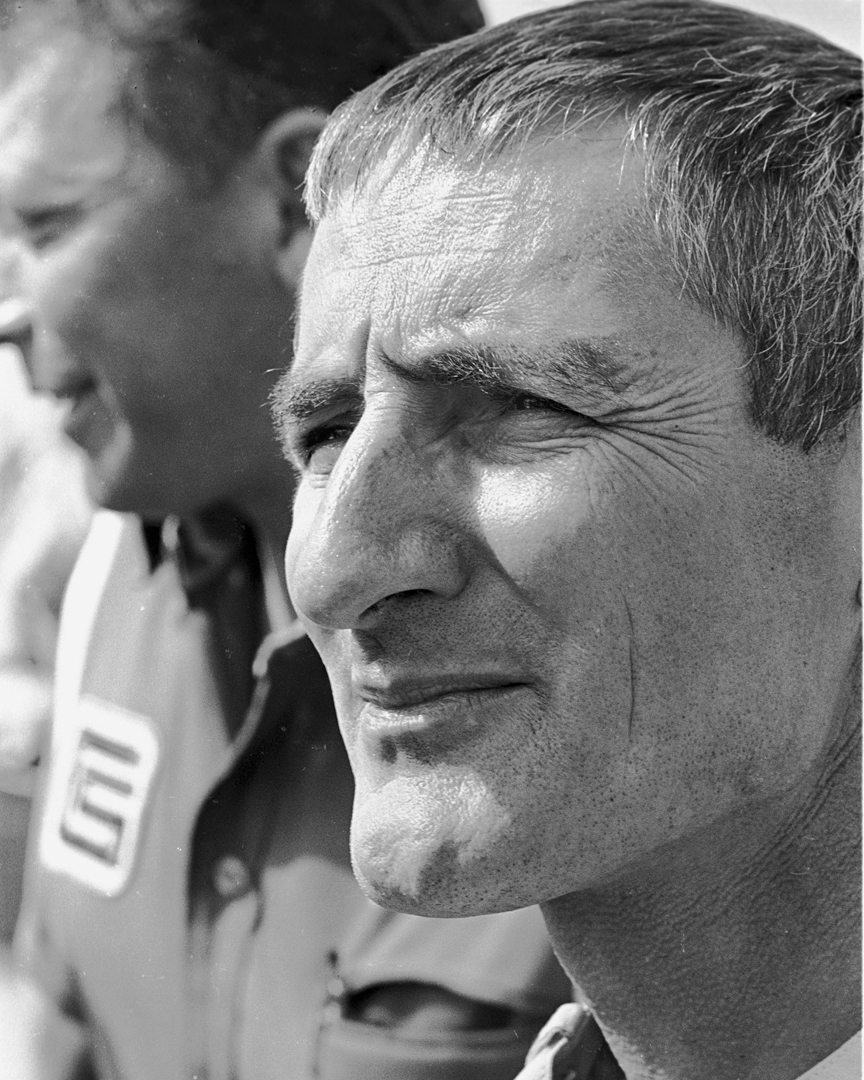

Not among Ken’s many talents was an ability to operate a successful business. His shop was padlocked by the government for non-payment of taxes. In 1963, Miles went to work for Carroll Shelby in positions that yielded success after success. He and Shelby became close friends. According to Shelby, “Ken was world-class and the best test driver I ever knew. He was also helpful to other drivers. He reminded me of Fangio in that regard. Before he came to Shelby American, he was known as a kind of hothead, but it never showed up during the years he was with me.”

Miles was also an author. Even though he dropped out of high school at age 16, he was very literate. Always an inveterate reader on all sorts of subjects, Ken was an excellent writer for various publications. The only problem was that he couldn’t type and his handwriting was atrocious. It was a dilemma for those of us who were tasked with putting his efforts into print.

During the second half of the fifties, a close friend, Dick Sherwin, and I published a monthly magazine, The Sports Car Journal. For a time, Ken wrote a column for us titled, “Racing Review.” In his March 1958 discourse, Miles attacked the subject of why amateurs race. It’s not only literate and amusing, but also pertinent today. (I reprinted it in my 2004 biography, Ken Miles.)

Photo: Dave Friedman

Looking back on the many times we were together, I can’t recall very much discussion about racing or cars. Some of the time then, I was studying for my masters degree in political science and then going to law school. Conversations with Ken that I can recall were often about politics and history.

During the time I knew them, the Miles family lived high on the hills above Hollywood. The home was graced with an impressive garden Ken had created. It was his pride and joy. The family included a Siamese cat who had been trained to do his business while sitting on the toilet, a fact I discovered one time when I had to use the facilities.

Ken and Mollie’s son, Peter, recently wrote me that he had run into some folks who remembered Ken with some animosity. At the time, I was aware that Ken often rubbed a few people the wrong way, mostly because he didn’t suffer fools—and sometimes let them know it in no uncertain terms. An outspoken person who held a number of grudges, not only against Miles, but also the Cal Club, was Gus Vignole, editor of MotoRacing, a bi-weekly newspaper of the time. His editorials often consisted of rants and raves.

For many of us—particularly the Miles and Evans families as well as Carroll Shelby—Ken’s death at only 48 years of age was a tragedy from which we have never fully recovered.