1959 Old Yeller Mk II

As with so many of the great racecars and specials of the ’50s, the success and genesis of the famed Old Yellers rests with a single talented individual, Max Balchowsky—or more properly, Max and his wife Ina.

Max Balchowsky was born on January 15, 1924 in Fairmont, West Virginia. Born into a multi-talented and eclectic family, Balchowsky’s father worked a variety of jobs including interior decorator, advertising designer and department store manager, while his school teacher mother invented a salve for burned skin called Cutigiene, which is still commercially available today.

With such a diverse background, it’s perhaps not surprising that the young Balchowsky became interested in a wide variety of things, most of them mechanical. By the age of 12, he was working in a bicycle shop building wheels and repairing bikes. With the onset of World War II, Balchowsky at the tender age of 19, found himself flying in the bowels of a B-24 bomber as a belly gunner. While making bombing runs over Yugoslavia and Romania, Balchowsky’s plane was shot down and his arm was badly injured as he parachuted out over friendly territory. When later asked by a reporter if he was scared, Balchowsky responded in his usual wry style, “It takes a long time to get scared if you’re a slow worker like me.”

After the war, Balchowsky moved out to California, where his brother Casper ran a gas station and transmission repair business in the town of South Gate. With money from his “GI Bill,” Balchowsky enrolled in a watch repair course, but soon learned that he had to take a $.75/hour job as a dishwasher to satisfy the terms of his government grant. Fortunately for Balchowsky, as he drove home from work in his hopped-up Roadster, he spied a pretty young girl by the name of Ina Wilson outside a nearby high school. If Balchowsky wasn’t smitten by Ina at first sight, he certainly must have been after he learned that Ina’s father owned an auto repair business nearby—and she could weld! By 1949, Ina had dropped out of high school and she and Max were soon wed. Later that year, the Balchowskys opened up their own shop, Hollywood Motors, which would become a Mecca for hot rods and performance tuning for the next 30 years. Founded on the slogan “We can replace anything with anything,” the Balchowskys and Hollywood Motors became renowned for transplanting high performance Cadillac and Buick motors into a wide variety of hot rods and race vehicles.

Like so many hot rodders of the period, by 1951 Balchowsky began road racing, first driving Bill Harrah’s Jaguar XK120 in the Reno Road Races, followed by stints in the Bu Ford Special and a Swallow Doretti that Balchowsky managed to shoe-horn a Buick V-8. However, fate would soon introduce an unusual racecar into Max and Ina’s lives that would indelibly forge Balchowsky’s reputation as a masterful, if not unorthodox, racecar builder.

Ugly Mongrel

Contrary to popular belief, the story of the Old Yellers doesn’t actually start in Southern California with Balchowsky, but in Phoenix, Arizona with another talented hot rodder named Dick Morgensen.

Morgensen owned an auto parts business that soon evolved into a performance machine shop replete with what was at the time the Phoenix area’s only engine dynamometer. Morgensen’s specialty was ringing the most from flathead Plymouth motors, which were being used in a variety of hot rods. However, by 1954 Morgensen turned his attention to building a “Special” for road racing. Using the greatest of hot rod traditions, he sourced parts for his new “Morgensen Special” from a variety of sources including a 6-cylinder Plymouth engine, DeSoto crank, hollow Ford front axle and a variety of other bits and pieces. The end result was not necessarily pretty, but it was well made and fast.

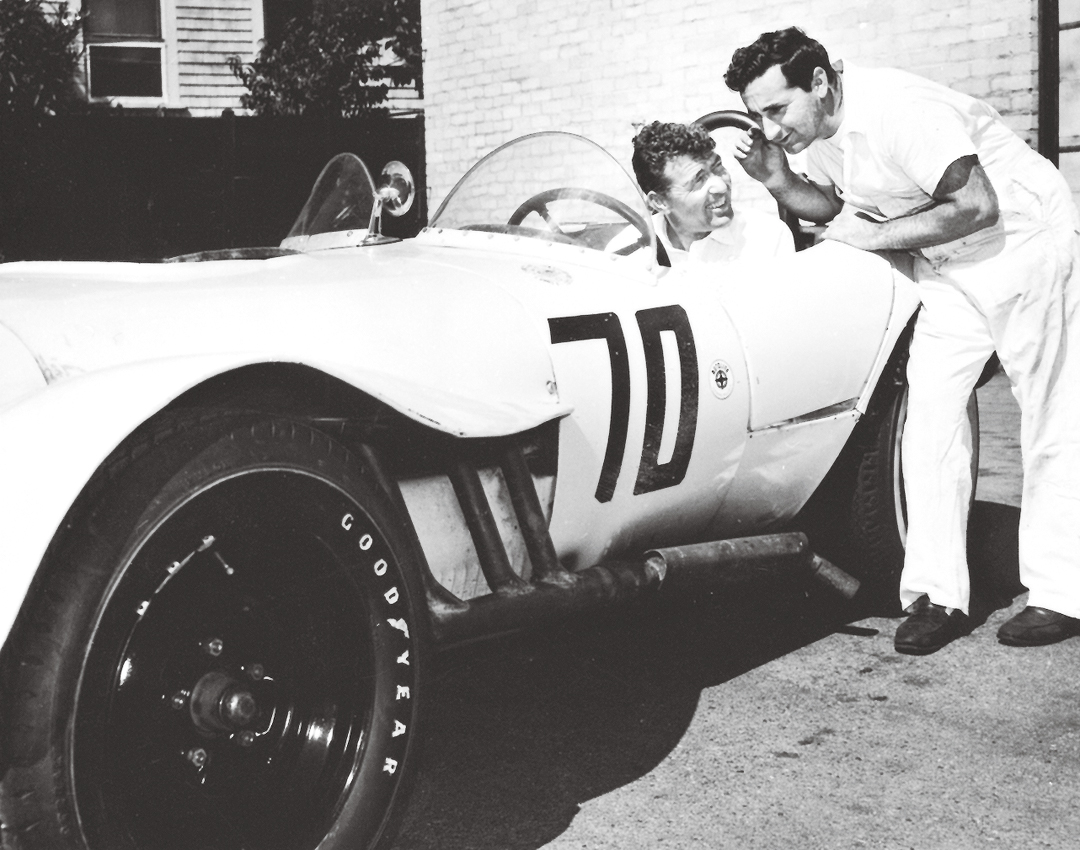

In the hands of local Arizona driver James Lee, the Morgensen Special won its first race in September 1954 at Santa Barbara, beating some heavy opposition that included Porfirio Rubirosa in a Ferrari Mondial. Also entered in other races that weekend at Santa Barbara were Morgensen’s friends Max and Ina Balchowsky, who undoubtedly were impressed with the Special’s performance straight out of the box.

Morgensen and Lee raced the Special with more successes until 1956, when Morgensen loaned the car to a nurse who wanted to race it in a “Powder-Puff” race at Torrey Pines. Tragically, the nurse failed to fasten her seat belt after the Le Mans start and was later killed when she lost control of the car going into Turn 1. Morgensen was devastated by the accident and in some ways felt responsible for the nurse’s death. Soured by the experience, Morgensen decided to put the car up for sale and, rather than towing it back to Phoenix, he left it on consignment at Balchowsky’s Hollywood Motors. However, it didn’t take long for Balchowsky to see many ways that he could improve on Morgensen’s creation. With the help of racer and investment banker friend Eric Hauser, Balchowsky bought the Morgensen Special and immediately began tearing it apart and modifying it.

Interestingly, it is at this point that it is commonly believed that Balchowsky installed the now famous Buick V-8 engine that has become so synonymous with the Old Yellers. However, Morgensen’s friend and driver James Lee contends that Morgensen had, in fact, installed the Buick V-8 prior to lending it to the nurse who was killed. In fact, this position is supported by photos printed in “Road & Track” of the car running at Willow Springs in 1956. Regardless of whose version of the story you believe, one fact that appears very clear is that Balchowsky developed this unit to the point that it could rival any equivalent engine of the period, including those made by Ferrari and Maserati.

Not long after Balchowsky had started working on the car, a photographer friend by the name of Lester Nehamkin stopped by the Hollywood Motors shop. Nehamkin, who was a Hollywood studio photographer, took one look at the Balchowskys’ new special and proclaimed it a mongrel not unlike the dog in Disney’s new motion picture “Old Yeller,” the story of a stray mongrel who loyally defended his adoptive family from a rabid wolf. Balchowsky liked this idea so much he not only adopted the name, but even painted the car a bold yellow not unlike the movie’s golden retriever star. Balchowsky and Hauser raced what was now known as Old Yeller Mk 1 in 1957 and 1958. Balchowsky showed great speed in his Old Yeller and at the 1958 Santa Barbara Road Races even broke the track record that was held by Lance Reventlow and his high-dollar Scarab. It was perhaps at this point that Balchowsky must have fully realized that he could build a competitive racecar for far less money than any of his competitors. This realization proved to be timely as Balchowsky and Hauser soon had a falling out that resulted in their splitting the car up—Hauser got the chassis and Balchowsky got the engine.

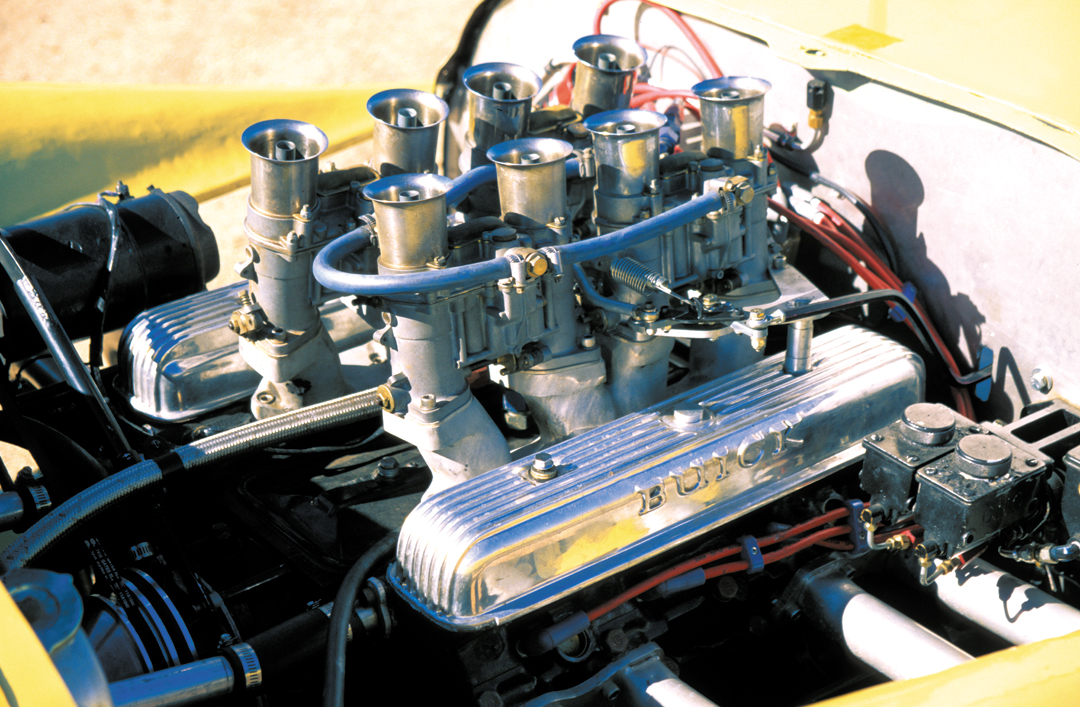

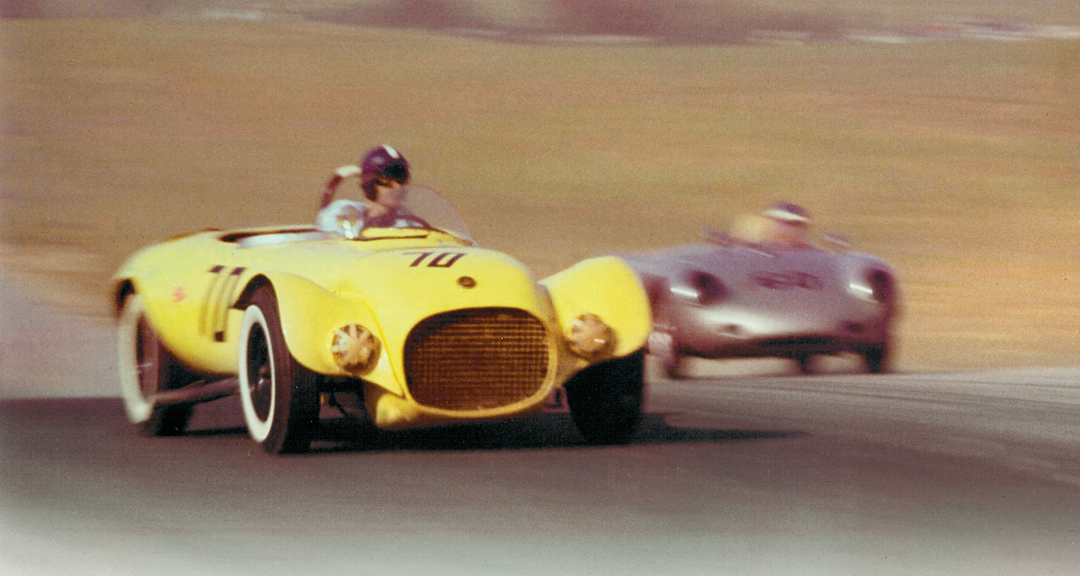

With seven weeks until the 1959 Fall Grand Prix at Riverside, Max and Ina set about building a second generation Old Yeller from scratch. Working in chalk on the Hollywood Motors shop floor, Balchowsky began laying out his new car around the 401 cu.in. (6.6-liter) Buick “Nailhead” engine that featured six Stromberg 97 (or sometimes Weber) carburetors mounted on an Edelbrock log-type manifold. The Buick powerplant belted out 305 bhp at 5400 rpm and transferred the power to the rear end through a Jaguar C-Type 4-speed transmission. Utilizing 1.75” x .058” chrome-moly tubing, Balchowsky built a frame that placed the Buick engine as far back in the chassis as possible and flared around the driver to protect him in the event of a side impact. The front suspension was a completely custom independent design comprised of parts from a variety of sources including drilled Jaguar upper and stamped Pontiac lower A-arms, with torsion bar springing and a quick Morris Minor steering rack. The rear suspension was a solid locked axle from a Studebaker Champion that sat on two asymmetrically mounted, semi-elliptical leaf springs and was located by a self-aligning and floating truss system designed by Balchowsky. Due to the constant cooling problems experienced with the hot-running Buick engine, Balchowsky chose to use a large Studebaker truck radiator, which dictated that when it came time to make the custom aluminum body, that the Old Yeller Mk II would have a somewhat large and ungainly radiator opening. While the bodywork was not necessarily pleasing to everyone’s eyes, it was highly practical, as Balchowsky designed it to attach with Dzus fasteners in such a way that the entire body could be removed in just a few minutes.

One of the most distinctive features of the early Old Yeller cars was Balchowsky’s choice of tires, more often than not recapped whitewalls. Keeping with Balchowsky’s illusion of “Junkyard” technology, most people assumed he used these tires because they were cheap; however, Balchowsky was much too clever for that. Throughout the ’50s, Balchowsky experimented with various forms of tires. Not satisfied with what was commercially available, Balchowsky worked with Gardner Reynolds on obtaining “special” recaps that were pulled from the rubber curing process 5 to 10 minutes early. By varying the amount of cure time, Balchowsky was able to get tires that were far more sticky than was readily available at the time. However, due to recurring problems with thrown treads, in 1959 Balchowsky was forced to look elsewhere and soon discovered that a common Chrysler station wagon tire (which was a white wall) had the right softness that he was looking for.

Photo: Nagamatsu Collection

Fast Buggy

While Max and Ina just missed completing the second Old Yeller in time for the Riverside Fall Grand Prix, it was completed soon thereafter for the princely sum of $1,472.55! Old Yeller Mk II’s first race was the November 1959 Hour Glass Field Road Races at San Diego, where the car showed great speed but was ultimately sidelined after a rock put a hole in the radiator. Unfortunately for the Balchowskys, this would not prove to be the only problem that year as Old Yeller Mk II struggled through the next five races with a frustrating array of teething problems that included everything from broken valves to blown tires—most of the time while leading the race!

Without a doubt, one of the biggest races of the 1960 season for Old Yeller was the April running of the Los Angeles Herald Examiner International Grand Prix held at Riverside Raceway. Wanting to show what his Old Yeller could do against some of road racing’s best, Balchowsky handed the Old Yeller over to Dan Gurney to drive in the race. In qualifying, Gurney posted the third fastest time, and on race day he shot into the lead and set a new racing track record. However, on the 40th lap—and with an 18 second lead—the harmonic dampner separated, breaking the crank and putting a hole in one of the pistons. Eventually, Carroll Shelby went on to win in a Maserati Bridcage, but Gurney showed the world what the ugly dog from Hollywood was capable of. In fact, after the race Gurney remarked, “This is as good as the finest car I’ve driven, and as comfortable as a baby buggy.”

Balchowsky resumed the driving duties for the next four races in 1960, scoring a 3rd place at Santa Barbara and the car’s first victory at Pomona, in June. Bobby Drake then drove the Yeller to victory at the Santa Maria Road Races, while Bob Bondurant took over the driving duties at Vaca Valley. In late July, Balchowsky convinced none other than Carroll Shelby to drive the Mk II at the Road America Grand Prix (the first professional race ever held at Road America) where it would again face an international field including Scarabs, Echidnas, Porsche RSKs, Listers and “streamliner” Birdcages. In qualifying, Shelby qualified 2nd next to the Scarab of Augie Pabst, even after doing damage to the car’s transmission. (Interestingly, contemporary accounts contend that while Balchowsky and Shelby went out for a night on the town, Balchowsky’s wife Ina rebuilt the transmission in time for the next day’s race!) In the race, Shelby built up a lead of over 51 seconds over Pabst’s Scarab until the much-abused rebuilt transmission finally gave up the ghost on lap 31.

As the 1960 season began to wind down, Bobby Drake was tapped to drive the Mk II at the October Times-Mirror Grand Prix at Riverside, where he finished an impressive 2nd to Billy Krause in a Birdcage and beat a stunning array of international stars that included Pabst (Scarab), Jeffords (Maserati), Shelby (Maserati), Salvadori (Cooper), Hill (Ferrari) and Jim Hall (Maserati). With one race left to go in the season, Balchowsky got back behind the wheel at Tucson where he fought a great race with old friend Morgensen, who beat him to 1st place driving no less a machine than a Ferrari Testa Rossa.

By the fall of 1960, Balchowsky had already begun building a new, more “sophisticated” replacement for Old Yeller Mk II and so sold the car on to Chuck Baldwin in January 1961. Baldwin raced the car in the Midwest, with one victory at Meadowdale, before putting the car up for sale in the spring of 1962 for $4,500! From there the car went to John Brophy who raced it in the SCCA before selling it the following year to Jerry Entin. Entin raced it in a variety of events in 1964, most notably a drag race at Irwindale where he won with a low 12-second E.T. and a speed of 127 mph in the quarter mile! However, by 1965 the car was sold to Balchowsky’s original Old Yeller partner, Eric Hauser, and subsequently changed hands two more times in the ’70s before finally passing to the car’s current owner Ernie Nagamatsu.

Driving Old Yeller

Photo: Nagamatsu Collection

Walking up to the Old Yeller, in the mountains outside of Los Angeles, one of the first things that I’m struck by is the car’s paint job. True to form, and exactly as Balchowsky had intended it, the Old Yeller looks like it’s been painted with a broom. While this is not what one is used to when looking at a very expensive ’50s sports racer, it is however a testament to owner Ernie Nagamatsu’s dedication to maintaining this car just as it was in period. Walking around the big yellow machine, I can see the scars from decades of hard racing, and yet it is the preservation of those scars (and the history behind them) that make this car so special.

We’d chosen a remote road, high up in the mountains outside of Los Angeles, for our test drive. Somehow it just felt right to test drive this outlaw Hollywood hot rod in such a rugged environment. Parked on a dirt road, far out in the countryside, the Yeller looked—well, strangely at home. Up close the car looks to the casual observer somewhat crude and agrarian. The fenders look like someone hastily cut them out of scrap aluminum and hammered them into rough shape, not bothering to remove the peen marks from the metal before painting. But this is Balchowsky’s great ruse, because as the old saying goes, “looks can be deceiving.”

Photo: Allen R. Kuhn

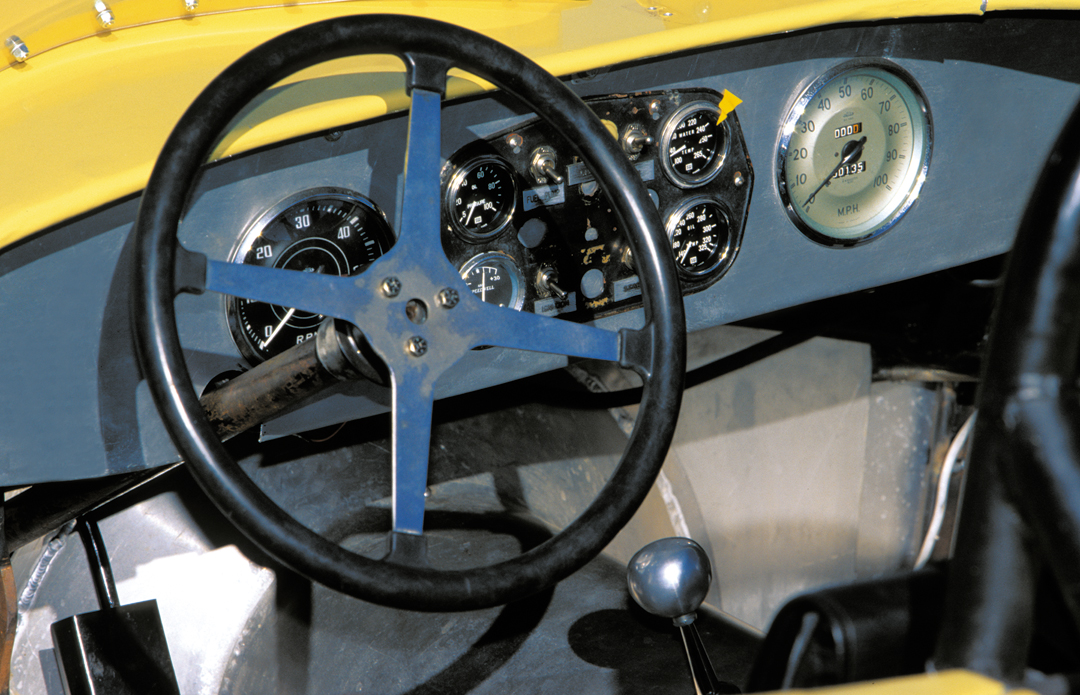

Not content to let our European editor Ed McDonough have the only hot rod racing experience (see last month’s Profile on the Baldwin “Payne” Special), I roll up the sleeves on my white T-shirt, open the small driver side door and clamber in. Since the frame of this car actually widens around the cockpit, I’m immediately cognizant of the sensation that the car is cradling me between the rear wheels. The cockpit is set up for current owner Nagamatsu, who is quite a bit shorter than I am, so I have to splay my legs around the big four-spoke steering wheel in order to reach the pedals. However, this car accommodated big Dan Gurney, so I know, given the appropriate set-up, it will service almost any size driver.

Nagamatsu has kept the cockpit just as it was in its day, with the exception of safety equipment. From the steering wheel to the mismatched period gauges, the car just oozes a sense of history. Gurney, Shelby, Drake, Balchowsky a lot of big names sat in this aluminum bucket seat, and that spirit permeates the cockpit today. After strapping myself in, the emergency cut-off is turned on and I’m given the thumbs up to fire her up. Flip on the ignition, crack the throttle, press the starter and the old dog barks to life. The Buick “Nailhead” V-8 fires immediately to life with a deep throaty growl and is quite content to tick over happily at idle.

Photo: Allen R. Kuhn

Because of my proximity to the pedals and the size of the steering wheel, I literally have to lift my left foot off the floor and pull it back to get it on top of the clutch pedal. The clutch action is heavy and it takes a fair bit of “oomph” to disengage the clutch, as I grab the big white shifter ball and select first gear. Feeding in a little bit of power as I let the clutch out, the Yeller and I gently drive down the country dirt road on my way to our two-lane test track. Let’s see you do that with a Testa Rossa!

Once out on the road, I loosen the Yeller’s leash and give her some boot. Immediately, the gentle lapdog turns into a Rottweiler. While the car’s size and shape belie its true weight, at just over 2,000 lbs the Yeller is quite light and, with over 300 horsepower on tap, it’s no wonder Jerry Entin was able to win drag races with it.

Photo: Nagamatsu Collection

Accelerating up to 6,000 rpm (redline being closer to 7,200 rpm), I grab the shifter and pull back for second. The throw on the Muncie 4-speed transmission now fitted to the car is very heavy and requires a fairly forceful effort, but is at the same time very positive. As I gather speed up this twisting mountain road, I can now start to feel what the car’s handling is really about. Again, for its size and appearance, the car feels surprisingly nimble. Turn-in is good as I dive into a left-hander and squeeze the accelerator out the other side. Crossing the road and turning into the subsequent right-hander, I’m pleasantly surprised how smooth the weight transfer is from one direction to the other.

Breaking for a tighter right-hander, I have a bit of a moment as I realize that the big drum brakes on the Yeller yetfully are not up to temperature. However, they ultimately get the job done and I snatch third and fourth gear on the other side as I tear off down a straighter stretch of road. As the speeds pick up, I soon notice so too does the car’s handling behavior. At higher speeds, the Yeller starts to feel a little hyper as the suspension and steering responsiveness now seem to want to react to every nuance in the road, which means a fair bit of darting and dodging over changes in the road surface.

Likewise, as I start to get more comfortable and drift the rear end a little bit, I again get that feeling that the car is stable, but potentially very nervous. For me, the Yeller drifted nicely and predictably, with no apparent bad manners, but I definitely came away with the feeling that it could really bite you if you don’t pay very close attention. Nagamatsu later told me that the setup for the rear end has proven critically important to dialing out this twitchiness.

In the end, as I pull back onto the dirt road, I begin to come to the realization that the handling characteristics that I was experiencing in the Yeller were very similar to a number of formula cars that I’ve driven that were supposedly setup loose for trained, fast drivers. And that is a level of sophistication that you just don’t expect from a car that, from the outside, looks like a junkyard dog. Which is just the way Max wanted it.

Owning an Old Yeller

All told, Balchowsky built 10 Old Yellers, but several were written off and one or two have gone missing, so that brings the available count down to about seven examples. However, the Petersen Museum owns Old Yeller Mk III, so in fact there are just a few other examples in private hands. Valuations on these cars is somewhat difficult because each one is physically different and all the cars vary in degrees of racing history. At the bottom end, the few examples with limited or no race history are likely worth from $150,000 to $200,000, while the cars with significant race wins could be worth well over $500,000—assuming that you can find an owner willing to part with his!

Specifications

Chassis: Tubular box-type frame made from 1.75″ x .049″ Chrome-Moly tubing

Wheelbase: 93″

Track: Front 56″ / Rear 55″

Overall Length: 150″

Height : 36″

Weight: 1,980 lbs.

Suspension: Front Independent with torsion bars. Rear Live axle, with asymmetrically mounted semi-elliptical springs and floating truss-locating device.

Engine: 1959 Buick V-8

Displacement: 401 cu.in. (6.6-liters)

Bore/Stroke: 43⁄16″ x 3.6″

Carburetion: Either six Stromberg 97 or four Weber downdraft carburetors.

Compression : 9.5:1

Transmission: Jaguar C-Type 4-speed (Muncie 4-speed currently)

Power: 305 bhp @ 5,400 rpm

Brakes: Buick-finned aluminum drums (Front & Rear)

Tires: Front 6.00 x 15, Rear 7.10 x 15

Resources

Steve McNamara

Max Balchowsky

Road & Track, November 1960

Rich Taylor

The American Sports Car

Old Cars, March 1978

Old Yellar Mark II

Trend Book, 196

Allan Girdler

American Road Racing Specials, 1934–70

Motorbooks International, 1990

ISBN # 0-87938-409-3

Special thanks to Ernie Nagamatsu and his fantastic crew for their generous help and support.