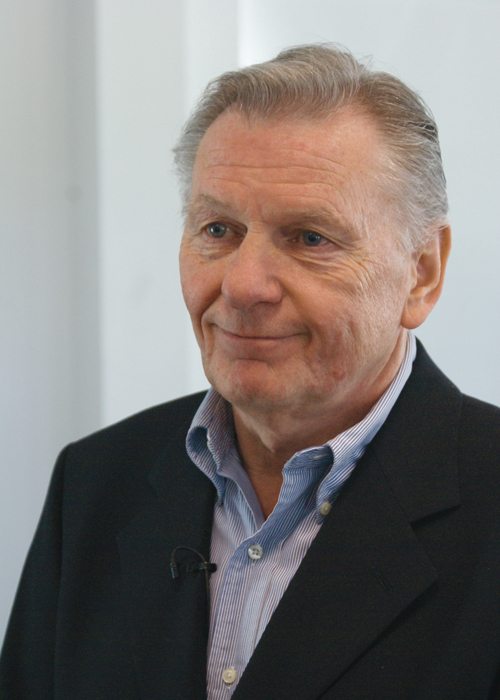

In the first two installments of our multi-part interview with John Barnard he discussed his early years with Lola and McLaren, how he developed his design philosophy and then looked at his experiences in Indycar racing and, back in Formula One, with McLaren and Ferrari. In this third and final segment, VR’s European Editor Mike Jiggle picks up the conversation with Barnard as he talks about his return to Ferrari and his subsequent stints with Benetton, Toyota, Arrows and Prost.

How did the ’88 season ‘pan out’ from your point of view?

Barnard: I felt the whole season was totally “messed up,” I’ll explain. Honda went off and designed a new engine with a 2.5-bar “popoff” valve. Our new V12 car wasn’t finished in time, so we had to run the turbo car again. In effect, the Ferrari ’88 car wasn’t much different from the ’87 car. I didn’t get too much involved with the ’88 racing season until we’d finished the normally aspirated car, that would be around April time. My first job, as far as the racing team was concerned, was to clear up all the politics, which I did with the aid of the Fiat guy, Giovanni Razelli. Certain people were removed from the team so we could get down to the serious business of motor racing. From around April 1988, I got more involved with the racing team. One of the first things the engine guys brought to my attention is that they believed—and I’m sure they were right—Honda had designed an inlet manifold system into their engine that “cheated” the popoff valve. So, instead of the Honda engine running at 2.5 bar, it would run at 3 bar, or something like that, which gave McLaren an enormous advantage over everyone else. Consequently, you can see why the 1988 McLaren was so successful, a wonderful car, but running with so much more horsepower and the two best drivers in the world.

Yet you had a timely win at Monza, just after Enzo’s death, and spoiled McLaren’s attempt to win all the races, didn’t you?

Barnard: Talking to the engine guys, we thought if McLaren can do it why can’t we? So, we fitted new manifolds for Monza that gave us around 2.9 bar and, lo and behold, we win—Berger 1st, Alboreto 2nd. The result showed me exactly where McLaren were at, they’d been going all year with this massive advantage. From my point of view, it wasn’t so much of working it out as it was shall we do it? Fundamentally, it was cheating the rules. At the end of the day, it was a case of “if you can’t beat them join them.” We, that’s Ferrari and McLaren, were the only teams with a serious turbo engine challenge that year—most of the others either weren’t in the same league as us or were running normally aspirated cars that were some 200 horsepower down compared with us—and they’d been going all year with this massive advantage. Taking all this into consideration, the 1988 McLaren could never be considered as one of the best racing cars of all time—as some do. Recently, I’ve seen articles in motor racing magazines where Gordon Murray and Steve Nichols are arguing whose car it was; for me it’s immaterial as the car was all about the engine. Unfortunately, the only time my new 1988 normally aspirated car ran on the track was in testing, but we developed it into the 1989 car, so we were ready for the 1989 season.[pullquote]

“Just because a guy has drawn part of a car, if he’s done that under the guidance of a technical director, he is not responsible for that design, the Technical Director is.”

[/pullquote]

That’s when Nigel Mansell joined Ferrari. Did he bring much to the team?

Barnard: Technically no, but he had an effect of limiting the politics at Maranello—purely because he was English. There was a mini English invasion of the team after I came along, well not just English, but German and French members to replace a few Italian personnel—Nigel had a cohesive spirit, which was a great help.

Wasn’t Michael Schumacher able to do the same with the team in later years?

Barnard: Yes, I wanted to take several McLaren staff with me when I started to set up the facility in the UK. However, Ron Dennis had had a meeting with Enzo where they came up with some agreement that precluded me from taking certain people away from McLaren. So, what could have been an exodus from McLaren became just a trickle. Fair play to Ron, he could see the writing on the wall and immediately did something about it. If the exodus had happened it would have given me far more power and capability within Ferrari.

Are you saying you could have brought similar success to Ferrari that Schumacher did?

Barnard: No, I don’t think so, but I could have quashed the unnecessary political situation and got on with the business of racing far quicker.

In 1989, the car instantly wins in Nigel’s hands, did that provide a good springboard to the season?

Barnard: Yes, for all the problems we’d had with the paddle shift system, it came good. We had a reasonable season that year. Unfortunately, following Enzo`s death, the Fiat guy Ghidella thought his job was to replace Enzo—he was never going to do that! As I had technical authority over it all then, I had to put my contract on the line and tell him we would run the paddle shift car for the coming season. If it didn’t work he could tear my contract up. Again, I’ve stuck my neck out, I believed what I was doing, I thought it was the only way to go and the risk was all down to me.

Photo: Paul Kooyman

Didn’t some people refer to that car as having a “duck-billed” nose?

Barnard: Yes, it was a styling feature more than anything. They changed it on the 1990 car. Before I left Ferrari in November 1989, I’d already drawn up the new 1990 car, which was in effect a development of the 1989 car with a few modifications, bigger fuel tank, revised electrical system and suspension geometry changes. The bodywork was tweaked through development done in the wind tunnel. A few years ago, Ferrari gave one of the 1990 cars to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. One of my kids was over there a year or so ago, a sign on the car credits it to both me and Steve Nichols (my successor at Ferrari), which was a change from when the car went into the museum where it had been credited only to me. I’m sorry, but Nichols shouldn’t be credited for just adding a few rounded corners to the bodywork—he certainly didn’t design the car it was all done prior to his engagement. Things like that really “tip me over.” Some people accuse me of wanting to have my finger on everything. Well, as Chief Designer I should, and do. Yes, I have a team working under me, but they all work under my instruction. Win or lose, the buck stops with me. However, as soon as something works, it’s amazing how many people pop out of the woodwork to claim responsibility—usually the same people who hide when things go wrong. I work the way I do because in the past I’ve left people to do things and regretted it. I don’t believe in working by committee—look at Red Bull, they don’t either.

Your next team was Benetton, how did that come to be?

Barnard: My deal with Benetton was that I would be given the funding to build up a brand-new technical setup for them, build a new factory, etc. Initially, a lot of my time was spent designing a new facility and spending time with architects and builders. I had little or no time to work on the car. Before I went there I knew they needed to invest a considerable amount of money on new premises and equipment. What really surprised me was the archaic aero design unit they had, they were so out of date. Rory Byrne was there and I’d watched the 1989 car at Jerez. It was frightening to watch. Fundamentally, it was all wrong aerodynamically. I implemented changes during the design of the 1990 car and that car wasn’t too bad, although a bit too ugly for my liking, winning two races at the end of the season. The team was badly in need of a new wind tunnel; they were using something that was nothing more than a student would use for a school project with quarter-scale models. There was no live adjustments, by that I mean the tunnel would have to be completely stopped, the model dismantled and relevant changes made before the test could continue. That meant they were more or less designing the aerodynamics around one ride height and pitch.

How did you get on with Nelson Piquet?

Barnard: By the time I’d got to Benetton, Nelson was in the twilight of his career. Don’t get me wrong, he was still a very astute character and still had a hunger to win. The 1990 season was the year of exotic fuels, we were sponsored by Mobil, who weren’t into doing anything other than providing their standard product. Nelson asked me how much we were losing out to the other teams who were using the exotic mixtures. I told him around 40 horsepower. He asked if I could assist with a non-standard mixture for us, I told him that Mobil weren’t interested but they wouldn’t stand in our way if we wanted to use something different. The problem wasn’t mixing, or having the fuel mixed, it was the logistics of getting the fuel to the circuit. Nelson told me not to worry he had a plan, if I could get the fuel he’d get it to the circuit. I got the fuel. It was put into 50-liter cans, we shrink-wrapped and vacuum-sealed it into plastic bags. Nelson, for his part, said he would fly the fuel directly to the circuit in his plane—which he did. Can you imagine it, a plane full of canned fuel? It was a flying bomb!!! By the time the plane got to the circuit the bags had expanded and looked like Michelin men—and all this for 40 hp, which he just had to have. He was such a canny character. Incidentally, we won the race.

Let’s face it, they all do something or other. In recent years, you cannot say Ferrari won all those championships without some kind of “assistance.”

Your short stay at Benetton was then followed by a “brief interlude” at Toyota?

Barnard: Brief, that’s the word. Toyota attracted me as it meant building something from scratch again, a blank sheet. Toyota had a wonderful dyno setup and factory in Norfolk, they’d needed it for their sportscar racing. I took my “usual crew” with me—people who had followed me from Ferrari to Benetton and now Toyota. Toyota at that time hadn’t really committed to F1, but were “fishing” to see what was possible. I was employed, with my crew, to start the process. Again, I was initially involved in designing a new facility to work from.

After a few months, I went to the main Toyota premises in Tokyo. The Toyota Company is owned by the two Toyoda brothers and a management system flows down from them. They weren’t at this meeting, and I thought it would be very difficult to get to them to discuss anything. Consequently, I thought if everything went well we were alright, money would come in no problem. My doubts and concerns were around the opposite side of the coin, would we be starved of resources? After a couple more meetings I still didn’t have the confidence that we would be backed. So, quite quickly I thought it was time to pack my bags.

Photo: Paul Kooyman

You returned to Ferrari, was it a different team to the one you’d left?

Barnard: I think I was contacted by Claudio Lombardi, who had replaced Cesare Fiorio. To answer your question, it was supposed to be a different team, but it turned out not to be. I had meetings with Luca di Montezemolo explaining what had happened before and how I felt things should be if I returned. I had to agree with him that the team couldn’t be run from the UK, as last time. Just six months prior to this meeting, Ferrari had sold the last facility I’d built to Ron Dennis, this took a headache away from McLaren as they needed somewhere to build their new road cars from—talk about helping the opposition!

While I agreed the team could not be run from the UK, I did propose that we create a new facility to design and develop the following year’s car. The Maranello team could continue to race the current car and I’d work in the UK on the new one. We went our separate ways to contemplate things, until another meeting was called in London. At this meeting were Luca, Niki Lauda, Harvey Postlethwaite, “Bubbles” Horsley came with me—I’m not too sure how or indeed why, but he was there. The meeting started, we discussed me running the new car design from the UK and Harvey running the race team from Maranello. Luca said to Harvey and me, “Why don’t you two guys go into another room and see if you think it could work.” Harvey and I left the room and after a while thought we could do it. We came back to the main meeting and said we’d agreed to give it a go and so it was. The bottom line was the money was good. That was until six months later when Harvey left Ferrari to join Tyrrell, Luca called me on the phone and asked, “What do we do for the next race?”

You were able to give Jean Alesi a car to win the Canadian GP, his only GP win?

Barnard: Jean was a lovely guy, and first and foremost a racer—a real “do or die” racer. He was never going to be an Alain Prost, holding back because he had enough points. Jean was always going to race flat out flag to flag. The whole Ferrari thing turned out to be the same as my first time with them. I designed the cars in UK with my team and built parts of the car in the UK and they did the rest at Maranello—not ideal, but that’s how it ended up.

… until Jean Todt came along?

Barnard: Jean Todt joined Ferrari about 18 months into my second spell with the team. Initially, he was just more or less an observer. Looking to see how things worked and ran. I suppose this would be around 1994. He made it fairly clear to me that this set up was far from ideal and it needed to be centralized around Maranello—I couldn’t disagree with him at all on that. We were desperately short-staffed. We ran all the aero stuff from a wind tunnel in Bristol owned by British Aerospace. We’d done a deal with them and built our own rolling road etc., but it was far from ideal. I’d ask every year for a certain budget which was immediately reduced by 20 percent.

When Michael Schumacher came along, even before he’d signed, and asked for this, or that, or the other, Jean Todt ensures it’s there for him. That’s how badly Ferrari wanted a driver of Michael’s caliber. I was frustrated as this is what we should have been doing two years before Michael joined to attract drivers of Michael’s ability. I remember Todt saying to me just before Michael came “if there’s anything you need just get it,” so we went out and spent half a million quid on new machines. If we had done that two years before we would have already been ready for the likes of Michael.

The car I’d produced for the 1995 season was a neat little car, both Gerhard Berger and Jean Alesi were quite complimentary about it. They enjoyed driving it. At the end of the season, we took the car down to Estoril in Spain and Michael came along to test it. He went out and was immediately a second quicker than the regular guys—Berger and Alesi. He even commented, “I could have won the championship easier with this car than the Benetton.” He went out in the new V10 “mule” car, and was less happy with that than the V12 car. One of the comments we’d had from Berger and Alesi about the 1995 V12 car was there was too much engine friction, so that when they lifted in a corner the car would become very unsettled from the rear. The new V10 car reduced this, however, Michael preferred the V12 to the V10 as he used the engine friction to help him drive through corners. We ended up with a 7-speed transmission just to give Michael what was lost from the V12—we could tune the rev range better with the extra gear. I was intrigued by this, but it needed a driver with total belief in his reactions.

Michael drove your car to his first Ferrari victory in 1996 at Barcelona?

Barnard: Yes, we had a good year and finished 3rd in the championship, winning again at Spa and Monza. At the end of the year, Jean Todt approached me and asked me if I would like the position of Technical Director/Chief Designer at Ferrari? While I was again delighted with the offer, my answer was as it had always been, I didn’t want to live in Italy. Once I’d declined, the writing was on the wall for me. Jean did ask me who he should have, he asked if I felt Ross Brawn could do the job—I thought he could, but only with Rory Byrne. So it was, they took other guys with them and the team was rebuilt. The last car I designed for Ferrari was the 1997 car, it was the year Michael won five Grands Prix, and finished on the podium on three other occasions, but all his season‘s points were taken from him after the collision with (Jacques) Villeneuve, at the last race in Jerez.

Did you keep B3 Technology, the Ferrari facility that you built in the UK?

Barnard: Ferrari allowed me to purchase it from them, they didn’t need it.

Wasn’t a Mr. Tom Walkinshaw your next customer?

Barnard: I’m not too sure how that came about. Tom had got hold of the Arrows team at that time. He must have come to me. He needed to push Arrows forward and needed an experienced technical team to assist him. I became the new Technical Director of Arrows. The intention was that Tom would buy B3 from me and integrate it into the Arrows facility at Leafield. I got involved in April 1997. They were running Damon Hill as a driver, I think Tom felt he needed a driver of Damon’s ability and standing, after all he was an ex-World Champion, to help with sponsorship and promotion. Yes, he had a limited shelf life, but that was okay at that time.

I set to work on the car they had, making aero and weight distribution changes to it. At Silverstone that year, I remember being at the circuit and really getting back into the groove of getting involved with a driver again. We did some changes from the Friday practice to the Saturday qualifying and moved Damon up the grid a few spots—which was very satisfying. It fires everyone up when that happens, it’s a great, great feeling and a boost to the team.

Of course, didn’t Arrows nearly score a win a few races later in Hungary?

Barnard: That was just incredible. Unfortunately, it was a case of a detail letting us down. An O-ring failed and that was our race, still we finished 2nd. It was a tire race, as Bridgestone was new to the game. This was where my initial work centered. We couldn’t get the front tires to work properly in the setup they had.

Photo: Brandon Malone / Action Images

I think the whole thing fell apart purely because Tom’s ideas outstripped what the team was capable of financially. Being a proud man, he didn’t really want to admit it. Instead of being up front, and saying we can’t do this, he’d rob Peter to pay Paul and do it, but something had to give. It was a sad situation, but I couldn’t work that way. Looking back, I was really pleased with the carbon gearbox we made for the car, it was the most successful in the pit lane.

I knew when I joined Arrows we were a middle to back-end team, I knew we hadn’t got the resources front running teams had. The engine was from Brian Hart, not a bad little unit, although I made several modifications to improve the car package. I just wish Tom would have been more up front with me. I became disillusioned and left. I have to say, I had fully left Arrows before joining Prost, and it wasn’t an easy thing for me to do.

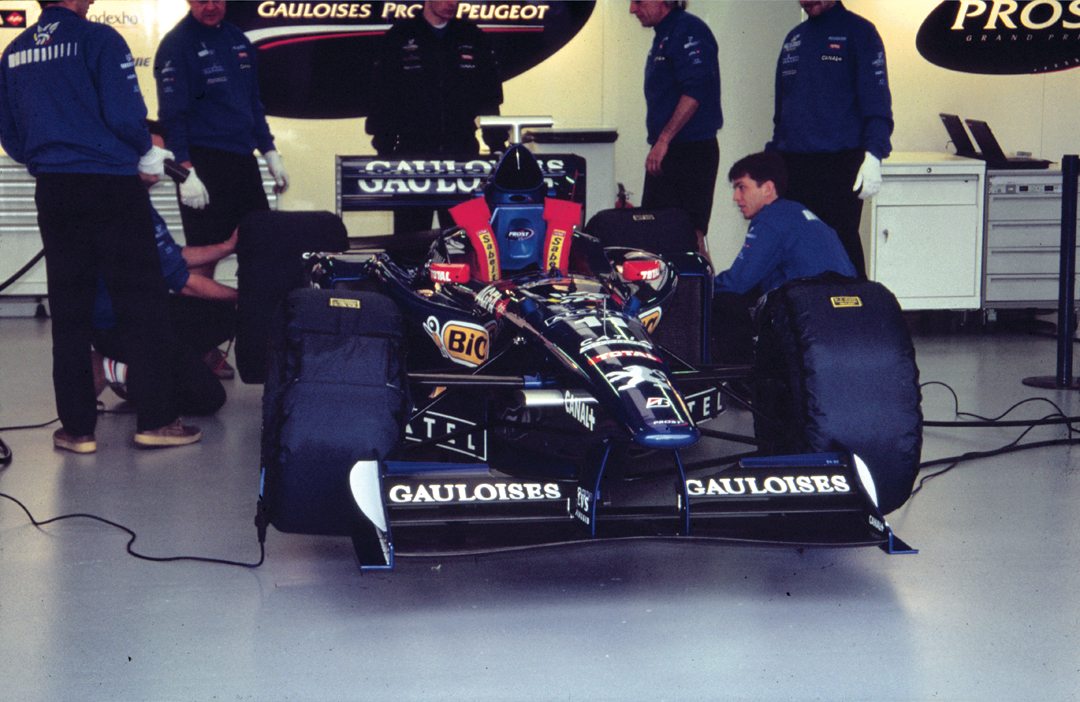

Was that a case of your old friend Alain Prost running a team by then and needing your help?

Barnard: Prosty was great as a guy, I helped him, but only as a consultant, and to bring the resources of B3 into the team—again, I wasn’t going to leave the UK on a permanent basis. One of the other reasons I left Tom at Arrows and helped Alain is that I thought their engine was a better power plant and I could do more with it. Peugeot were a main manufacturer. The first engine we had was more of a sportscar engine than a formula engine, it was reasonably powerful, but heavy—that was the first year, 1999. The next year, Alain had brought Alan Jenkins in as technical director/chief designer, and he’d asked Peugeot to build an engine more suited to F1 than sportscars, which they did. Unfortunately, they didn’t have the experience and there were inherent problems that resulted in a drop in power—a backward move.

I think the Prost team was a clear example of a driver not being able to become a team owner. No matter how good drivers are, they only see the end product when they’re racing. It’s a whole different world away from just driving at the circuit. No matter how many times a driver visits a factory while he’s driving, he is still unaware of what it takes to run the team—Alain was no different.

Didn’t that about draw a line under your F1 career?

Barnard: Yes, in a way I wish the Arrows thing could have worked better. I was looking forward to picking up a few points here and there and maybe the odd win or two, who knows. I came to realize that people were looking at me as though I had got some sort of magic button and I could change their team into a winning team instantly. That was far from the point. There is no way a small team can compete with the McLaren and Ferrari teams of this world with half the facilities and half the budget. Time, too, is something people take for granted, it takes time to build success—overnight success takes a lot of hard work and preparation.

So, looking back, give me some high points—what were great moments for you?

Barnard: It has to be the Chaparral, it was a defining moment in my career, and was done at such low cost and meager means in comparison to what was to come in my time. Winning the Indy 500 and Indy Car Championship, it doesn’t come any better than that. I basically drew it up on a drawing board in my dad’s front room since my wife, who was pregnant with our first child, and I had just come back from the USA. I had Gordon Kimball come over from the USA to be my assistant, since we had already worked together at Vel’s. I had one other guy, Dave Pollard, help for a short time making drawings, but that was it. Three cars were built in Luton and shipped out to Midland, Texas, a shoestring operation, but successful! It was also a white piece of paper job, nothing to start from.

The other thing was testing the 1984 McLaren turbo car, when the car fired up straight out of the box, Alain knew he could win the championship with it.

I think I’d like to be remembered for the things people now take as standard in F1, there’s quite a list believe me—I’ll look to doing it one day. One thing I would like to see, as I’ve alluded to in this interview, is the right people being recognized for their designs. Just because a guy in an office has drawn a part of a car, or whatever, if he has done that under the guidance of a Technical Director then he is not responsible for that design, the Technical Director is. The other thing is that an F1 team has to have a pyramid command structure, for both the technical side and the commercial side. You have to have a figurehead at the top of each pyramid, responsible for it all. An F1 team cannot be run by a committee, I believe that’s the difference today between Red Bull, who are so successful, and McLaren, who are the nearly men.