1931 Alfa Romeo 8C 2300

He is probably not everyone’s perception of an Italian, but Vittorio Jano—who almost single-handedly made Alfa Romeo’s name during his time with the company—was an exceptional organizer and disciplinarian. Enzo Ferrari recalled that he “took command in Milan (and) established an iron military discipline…” but, how did he get there and what did he do?

On April 22, 1891, Jano was born in the small town of San Giorgio Canavese, northeast of Turin in the direction of Ivrea. He always said that he thought his surname was derived from the middle-European “Janos” and that his family was the result of Hungarian soldiers being in Italy in the wars of the first half of the 18th century and electing to stay on after they were over.

Jano’s father was Technical Director of the Turin Arsenale and was delighted when he noted mechanical interests in his son who, by the time he was 18, had completed a technical course at the Turin Istituto Professionale Operaio in Corso San Maurizio. His first job was as a drawing tracer at the S.T.A.R (Societa Torinese Automobile Rapid) works that had been started by Giovanni Ceirano. The company increased in stature during Jano’s period of employment such that by the time he left, in 1911, it was building seven different models of car, as well as buses and commercial vehicles.

He had been talent-spotted at S.T.A.R by Fiat’s Engineer Guido Fornaca, who had noted the extraordinary abilities of Jano and, once he was with Fiat, both Fornaca and Carlo Cavalli kept him under their wings. He became the personal pupil of the latter and forever after noted his debt to Cavalli. He is reputed to have been involved with the design of the 1914 Fiat S57 Grand Prix car, and it was after the Lyon Grand Prix of that year that, according to Alfa historian Angela Cherrett, a close collaborator noted his ability to manage a team stating that he was “…a lion in the pits…”

By 1917, he was part of the Fiat design team and had a hand in the 801/3 and successful 804 Grand Prix cars. He became responsible for their preparation for events and accompanied the 805s to the first European Grand Prix at Monza in 1923. While working as a test driver at Fiat, he became close colleagues and eventually close friends, with Luigi Bazzi who, not long after, left Fiat for Alfa Romeo.

Rewind to the beginning of the First World War and Nicola Romeo—who had obtained the franchise to sell American Ingersoll earth-moving and industrial equipment and, under wartime conditions, was making a considerable amount of money doing this—gradually found that his supplies were drying up due to submarine activity in the Atlantic. The Americans sent him all the necessary paperwork and suggested he make the equipment himself so he took over the old Darracq works in Milan and built the machinery there. This was fine, but when the Armistice happened, all of a sudden his market dried up, leaving him wondering what to do. Realizing there might be a market for cars, he decided to turn his factory back into a car manufacturer and so took over Giuseppe Merosi’s struggling ALFA concern and renamed the new company, Alfa Romeo.

With the company had come Merosi himself, who was responsible for the RL model Alfa and for enhancing the reputation of the new company. However, his first Grand Prix car, the P1, was mediocre and apparently evil-handling, so Nicola Romeo called a meeting to discuss what should be done. Present at the meeting was Enzo Ferrari, who was a general trouble-shooter and dealer at the time and Luigi Bazzi, fresh from Fiat. Realizing that he needed a new car and a new designer, Romeo asked Ferrari to go to Turin and find someone new. Bazzi had suggested Jano.

That was one story.

Another, according to Ferrari, is that he was asked by Alfa manager Giorgio Rimini to find someone and Enzo took it upon himself to ask Bazzi whereupon, having been told about Jano he went straight to Turin, knocked on the Fiat man’s door and persuaded him to defect to Milan.

The real story is probably a mixture of these two. Jano was a dyed-in-the-wool Piemontese and it would have taken more than the word of Ferrari, an underling in his eyes, to persuade him to switch to Lombardia. Jano himself is later recorded as saying that he asked Ferrari who on earth he was and could he speak to someone at Alfa more senior! I would give a lot to have seen Enzo’s face at that moment.

Much better pay and conditions at Arese finally persuaded him to take his wife to Milan and they settled into an apartment on the Corso Sempione in October 1923. Within nine months, Jano had designed and built his first Alfa Romeo racing car, the immortal P2.

In fact, all his cars were immortal. He literally made Alfa Romeo during the 16 years up to the war, and he started off the mark in late 1923 at a pace that was almost difficult for others to keep up with. As Enzo Ferrari said, “…Jano took command in Milan…and in scant months created the P2 from scratch….”

The engineer’s detractors would have it that he took ideas from Fiat, but even if he did, he already knew where their original designs’ weaknesses were and in the P2 sought to eliminate them. It has been variously reported, but essentially as quoted by Angela Cherrett, Nicola Romeo took Jano aside when he arrived and said, “Listen, I don’t expect you to build me a car which will beat everyone, but I do want one which will make a name for Alfa….”

In 1923, the best GP car in the world was the Fiat 805, in which Jano had had a hand. He knew it inside out and where its failings were. Its straight-eight cylinders were built up in blocks of four and were prone to flexing due to thermal distortion, so Jano designed the P2 to be built up in blocks of two. Its twin camshafts were driven by spur gears instead of bevels for ease of adjustment, and the supercharger was smaller and ran faster. It all added up to a better car, and when it first ran at Cremona on June 9th 1924, it ran away with the race with Antonio Ascari at the wheel. On August 3 it made Alfa’s name forever when Giuseppe Campari won the gruelling 800-kilometer GP at Lyon with one of the cars. It cannot be overestimated how important this win was. Alfa came from nowhere with no previous experience or record and beat all comers. Fiat soon withdrew from racing and the Italian center of racing shifted from Turin to Milan. The equivalent today would be if some unknown team like Lancia suddenly and unexpectedly turned up at Silverstone for the British GP and walked away from McLaren, Mercedes, Ferrari and Red Bull to win first time out. The drivers described the P2 as un gioello (a jewel) and Jano’s farsightedness included improving performance by working closely with fuel companies to allow the engines to deliver more power and reliability.

So fast were the cars that at Spa, in 1925, Ascari’s lead was so huge that the crowd was beginning to heckle the Alfa team as they were making the race so boring, so Jano set up a table in the pit lane, properly laid with cutlery and tablecloth, and served his drivers a meal! They still went on to win by no less than 22 minutes!

Road cars too were on Jano’s agenda and in 1925 his first, the 1500, appeared. Once again, it was a light, fast and reliable car beautifully engineered with attention to detail such as the innovative way that its valves could be adjusted by means of a screwdriver. In fact, Jano could find no further way of improving the system until his Lancia D50 V8 of 1954.

In 1927, Jano was given the responsibility of designing new aircraft engines, and his output was so successful and prolific that by 1932 the Italian Government’s orders for new planes swamped the motorcar production division. Things didn’t stop there either as, in 1931, the engineer was put in charge of Alfa’s new truck and bus division. By ’37 he was responsible for 14 different new commercial and passenger-carrying vehicle types.

Back on the car side, the P2s were sold when the Grand Prix formula changed, but they kept on winning other races in the hands of the likes of Brilli Peri and Varzi. The factory then bought back three of the six and with modifications they went on winning, most notably at the 1930 Targa Florio in Varzi’s hands. These cars had front ends very similar to the 1750 supercharged models.

While the 1500/1750/1900 range was selling well and proving successful in competition, Jano was forging ahead with the next generation of road and racing cars. He had alongside him a formidable team of men consisting of Luigi Fusi, Gioachino Colombo and Secondo Molino. The latter left for a job at Bianchi, but the next Alfa Romeo was the 8C 2300 which Jano later shrugged off as “no masterpiece of mine” suggesting that the chassis was too heavy. History would probably suggest that he was wrong, as this was a car with an engine of “breathtaking architectural elegance” according to noted historian Griff Borgeson.

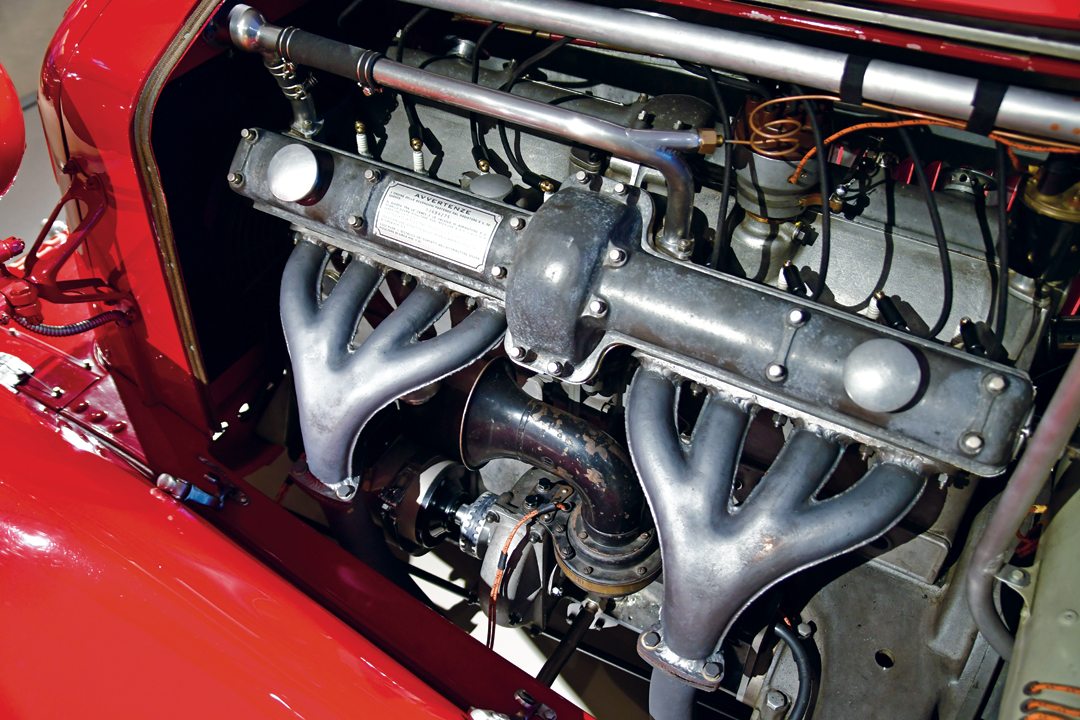

As the car’s title suggests, this engine was of eight cylinders, but this was nothing unusual in the world of quality cars at the time. What was unusual was the architecture of the unit. Jano had effectively divided it in half, with two cast-iron blocks of four cylinders mounted on an aluminum crankcase common to both. Each of these blocks had their own cylinder heads manufactured from aluminum, and even the crankshaft was in two pieces with each four-cylinder section joined at the center by a cascade of gears. One of these drove the supercharger, water and oil pumps, while the other, via a gear-train, was responsible for the camshafts, of which there were two overhead that were not divided.

With the technology available at the time, the huge advantage this arrangement had over, say a Bugatti, was that it eliminated the possibility of a long crankshaft flexing and thus eliminated valve timing aberrations due to vibrations and therefore improved ultimate reliability.

Jano was confident enough with plain bearings to use them throughout, and the whole unit had an elegant symmetry so that the valves, both intake and exhaust, were the same and this led to the main Achilles heel of the unit after long, hard use as the water cooling area around each was the same. The bore and stroke were 65-mm x 88-mm, which was exactly the same as the previous 6C model so that we can describe the 8C as virtually a six with two more cylinders added. Luigi Fusi quotes power as initially being 142-bhp at 5,000 rpm.

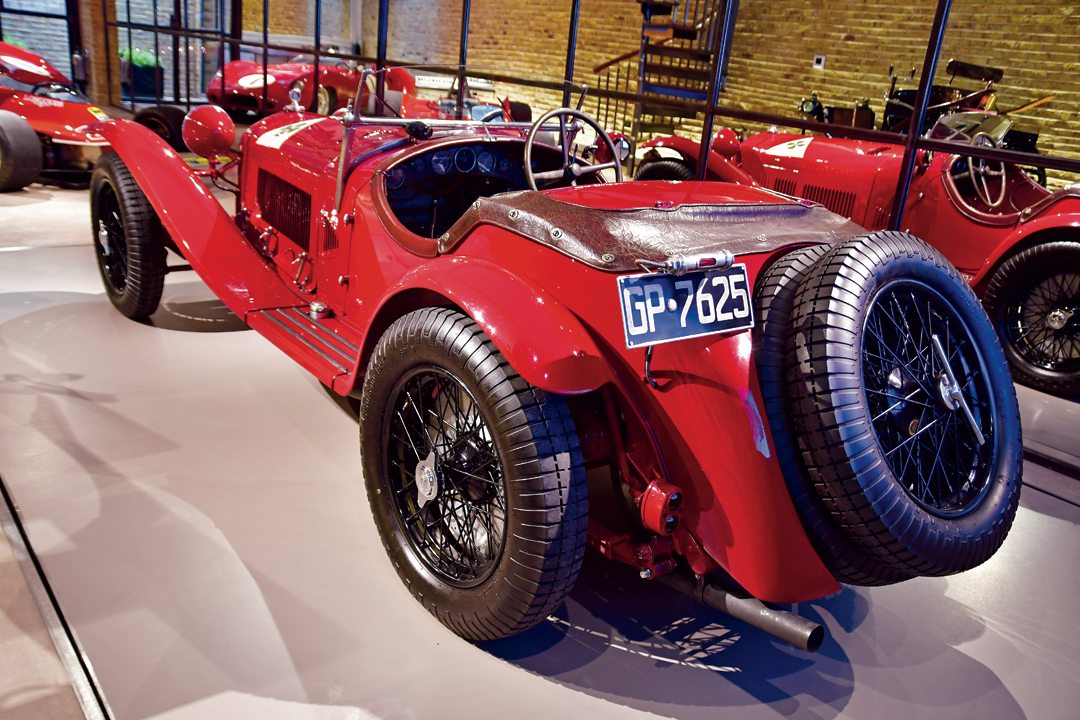

“Our” car featured here is chassis 2111006, and is thus the sixth to be manufactured of the 50 First Series cars that debuted in 1931. The model would, by the end of production in 1934, amount to just over 180 chassis, and these consisted of the Corto, the Lungo, the Spider Corsa, the Monza and the Le Mans. This car is one of the much-coveted Corto, or short-chassised cars and is endowed with a rakish aluminum Zagato body, the looks of which have seldom been surpassed.

Originally, it would have had a slightly sloping and deeper cascading radiator grill as seen in the early photographs of the car in action, but at some stage in the car’s life it was changed to the current, shorter and cowled Monza-style front end.

Being only the sixth example produced it is highly likely that all the famous then-current Alfa Romeo test drivers had a turn at its wheel, but it seems it was not ready in time for the model’s debut event, the 1931 Mille Miglia, nor the intended Targa Florio of that same year. However, by July all was complete and 06 was entered for the Belgian Grand Prix, demonstrating the versatility of these cars.

Three 8Cs were run, and two of these, driven by Tazio Nuvolari and Baconin Borzacchini, as well as Chassis 06 driven by Ferdinando Minoia and Giovanni Minozzi, finished the gruelling event in 2nd and 3rd places. Initially, Chiron’s Bugatti had set the pace over the 14.8-kilometer circuit, which had to be completed 88 times for 1320-kilometers, but by halfway he was out and Nuvolari held a small lead, only for Grover-Williams to pass in the ninth hour after a lightning pit stop for new brakes and a driver change. As an example of the 8C 2300s versatility, the fourth car home was Henry Birkin’s long-chassis (Lungo) Le Mans version.

In the heat of an Italian August, the Coppa Ciano (named for Navy hero Costanzo Ciano) took place over a 20-kilometer circuit on the Tuscany coast . In this race, Nuvolari himself was at the wheel of 06, which was one of four 8Cs prepared and entered by Enzo Ferrari’s quasi-works team. By now our car featured the Monza cowl on its nose and would thus have looked similar to today except it carried only cycle-type fenders.

The cars were started at one-minute intervals and the slowest were set off first, in the style of the Mille Miglia. Achille Varzi, in a Bugatti, was Nuvolari’s target, and on the first lap 06 was 11 seconds behind the blue car, due to Nuvolari being delayed by slower cars on the twisty and narrow parts of the track. Trailing Varzi by only four seconds on the second lap and despite the latter having to pit with a puncture, “the flying Mantuan made a series of very fast laps, the best being the sixth,” said doyen journalist Giovanni Canestrini, and this put him into an apparently unassailable lead until an alleged moment off-road delayed him. He still finished 14 seconds behind Chiron’s Bugatti, which had overtaken him, but because he had started one minute behind he won the race by 46 seconds.

Over the winter of 1931-’32, Jano would travel frequently to the Scuderia Ferrari workshops, in Modena, to supervise upgrades to the team 8Cs, of which 06 was included. Main reason for this was that Alfa was being urged to win the ’32 Mille Miglia at all costs, and beat the German Mercedes team. Shorter front springs were fitted to 06 to sharpen up the handling.

Come April and Brescia, the car had been allocated to Pietro Ghersi with Giulio Ramponi alongside him. Effectively the circuit ran anti-clockwise to the course we know in today’s retrospective. The complete Ferrari team of nine cars, headed by a 1750GTC touring car, convoyed from Modena to the start—it must have been a superb sight to an Alfisti—and even had time for a team photo en route with everyone clustered around chassis 06.

Just after 11 in the morning the fastest cars came to the starting line and Ghersi was the first of the Ferrari team to leave Brescia with 1,000 miles of arduous and thrilling driving ahead of him, with Ramponi alongside in the passenger seat.

There seem to be various stories of what happened, one of which suggests that Ramponi had taken over the driving to give Ghersi a rest, but 06 was out by the time Florence was reached. The normally reliable W. F. Bradley reported quite specifically in the Autocar of April 15, 1932, that, as he entered the Piazza Michel Angelo in Florence, “under the gaze of several thousand spectators, Ghersi over-estimated his speed, skidded wildly as he attempted to take a right-angle bend and hit a post with fatal results to his machine and slight injuries to himself and Ramponi. A few moments later cheers arose from the crowd…” because Nuvolari had arrived, but the report continued that the great man was distracted by the sight of Ghersi in trouble such that he, himself, went off the road into retirement.

Whatever the truth, it was Borzacchini in another Ferrari Alfa 8C who came home the deserving winner, with teammate Count Trossi 2nd in another team 8C, while 06 went back to the workshop for repair.

The pace of events was fast and furious as the team had little time to turn 06 around before it was despatched to Sicily for the May running of the Coppa Messina. Again, Ghersi was at the wheel and this time he made it stick with a commanding win and it is worth mentioning, as an example of just how adaptable the 8Cs were, that in the meantime Nuvolari had used one to win the Monaco Grand Prix.

So Ghersi won in Sicily by two minutes and six seconds from teammate Brivio, after just short of five hours racing around the 52-kilometer circuit. His fastest lap occupied 35 minutes 57.8 seconds, for an average speed of 86.7kph.

Chassis 06 and other 8Cs continued their winning ways at the summer running of the Coppa Gran Sasso d’Italia in the Abruzzi before being sold off in the autumn because Ferrari was concentrating on developing and running Jano’s new P3 single-seater. Registered GR (Grosetto) 1961 it went to Jacques “Giacomo” De Rham, but by March 1933 he had moved 06 on to the Alfa dealer in Rome from where there is a possibility it was loaned back to Ferrari for the ’33 Mille Miglia. The car also had its definitive Zagato body by this time as the racing lightweight example would have been virtually worn out considering the activity the car had undertaken.

A new owner in Rome from May ’33 was one Giuseppe de Filippis, who lived in via Savoia near the Parco Villa Borghese but he was persuaded to sell the car, now registered Roma35072, to Pietro Santi for the ’34 Mille Miglia—old racing cars never die. Sadly it failed to finish, but had managed to get to Rome in the respectable time of six and a half hours.

After passing through the hands of several custodians in Northern Italy, 06 found itself in the possession of future Alfetta Grand Prix driver Felice Bonetto, and for the first time 06 was sold out of Italy to Luxembourgois dentist Paul Decker in 1936 who, despite the war, prized the car and kept it well for 10 years even indulging in some light competition, but also hiding it away from prying Nazi eyes. Another ten years passed and 06 was sold to the USA by dealer Jean de Dobbeleer in Brussels. It went to Alfa enthusiast Ed Roy from Boston for $520, remaining in the country until the 1970s when it recrossed the Atlantic into the hands of arch Alfa man Rodney Felton in the UK, who carried out a total and meticulous rebuild before taking to the circuits with the VSCC, always driving 06 to race meetings. By now it was registered GP7625.

Felton protected the valuable Zagato body from damage by racing 06 with a substitute Monza lightweight example and beat the Bugattis in the VSCC’s prestigious Williams Trophy race twice during the 1980s, when it was also tested by classic car magazines which produced a timed 0-60 mph time of 5.8 seconds and 0-100 mph of 15.5 seconds, achieving 120 mph pitched against Geoffrey St. John’s Bugatti T51.

The peripatetic 06 was on the move again across the Atlantic when it was sold to Bruce Vanyo in California, who organized the refitting of the gorgeous Zagato fenders that were sourced from Ned Reich. Back to Europe the car came again in 1996, via Alain de Cadanet, to a Dutch collection and into the hands of Alfa expert Neil Twyman for another detailed restoration before display at Goodwood’s Cartier Style et Luxe in 2015, winning a special supercharged class.

Latterly, this fabulous ex-Nuvolari Scuderia Ferrari 8C has been in the hands of the prestigious dealer Gregor Fisken and is available for viewing to potential clients in his superb Queens Gate Mews premises in London.

Driving Pre-War Alfas

I have been lucky enough to drive both Jano’s earlier 6C 1500 and 8C and the immediate impression is not how fast they are—how they go—but how well and easily they handle and stop.

No wonder their competition record is so incredibly long and comprehensive when it is possible to drive these winners rapidly within a very short space of time at the wheel. I have done this both on the road and on the track and it is possible to identify immediately, having experienced the lightness of the controls of the 6C, how and where Jano sought to improve the dynamics of the breed, but he clearly did so with little detriment to the feel—at least at the very non-Nuvolari-like, pedestrian speeds that I was able to achieve. Obviously, the 8C is considerably beefier than its smaller, lighter sibling, but the bloodline is so clearly there.

From the exit of Luffield at Silverstone, the power impresses and that straight-eight boom gets louder in steps until it’s time to change down for Copse. With modern rubber compounds, in albeit vintage construction tires, the road-holding of the Alfa displays with pleasure why Felton gained so much pleasure from this car and from beating the Bugattis back in the 1980s. It doesn’t so much slide, as power through, and makes light of the upgrade to Maggots. Once over the summit, it’s time to apply those huge finned brakes to ensure safe negotiation of Beckets.

Another surprise. There isn’t a lot of body lean so Jano’s front suspension modifications over the ’31-’32 winter really worked. Then there’s the pleasure of that booming power again as you point that so satisfyingly long bonnet back over the rise and down to Brooklands’ left-hander.

The engine simply feels unburstable and inspires immense confidence, as it must have done for the drivers of ten-hour Grands Prix. In fact, browsing period results it’s difficult to find instances of engine failure.

Now, the most difficult bit. To be honest, vintage cars were designed and built like they were to make the most of the road conditions of the period and it is easy to understand the tail-sliding tendencies of the cars on a loose-surfaced Futa pass, for instance. The ultra-high adhesive qualities of Silverstone’s surface are such that the g-forces are high exiting the left-handed Brooklands, but immediately one is faced with the right-handed Luffield. This was the only time when it actually felt you were in a non-current vehicle, as the right-leaning car and, by extrapolation, left-leaning you, are immediately snapped into left-leaning car and—you’d better be quick, at the speeds an 8C is achieving—a right-leaning you. That high driving position, roomy cockpit and sticky surface/tire compounds add up to a feeling of almost leaning over a motorcycle as the weight load transfers from one side to the other. Of course, on that legendary 1930s Futa Pass, the car would have just slid round, using the chassis as much as the suspension. It only remains to see just how much power can be piled on through the long Luffield to take us back to our starting point.

These cars are as good as they are made out to be – simple as that. Like the Ferrari 250 GTO, their superlatives really are there in the dynamics and, not forgetting, the looks.

Grazie mille, Jano. Alfa Romeo, Fiat, Lancia, Ferrari and we owe him a huge debt.

SPECIFICATION

Engine: Straight eight cylinders, 2336-cc, DOHC with Memini carburetor feeding an Alfa Romeo supercharger. The block was in two parts of cast-iron and they were mounted on a common aluminium crankcase.

Gearbox: Four speed and reverse with lock-out on gate.

Brakes: Finned drums all round operated mechanically.

Steering: Right-hand drive by steering box.

Suspension: Semi-elliptic springs front and rear with friction shock absorbers, the rear being adjustable from the driving seat. Live rear axle.

Track: 1.38mtr front and rear.

Wheels: Rudge Whitworth wires all round 5.50-19

Wheelbase: 2111006 Corto 2.75mtr. Telaio Lungo 3.10mtr.

Length: Varies according to bodywork fitted.

Width: As above

Height: As above

Weight: Corto is approximately 1000kg with two spare wheels. Lungo approximately 1200kg.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author wishes to thank Gregor Fisken and the writings of the late Griff Borgeson and Angela Cherrett on this subject, as well as William Court and W F Bradley.