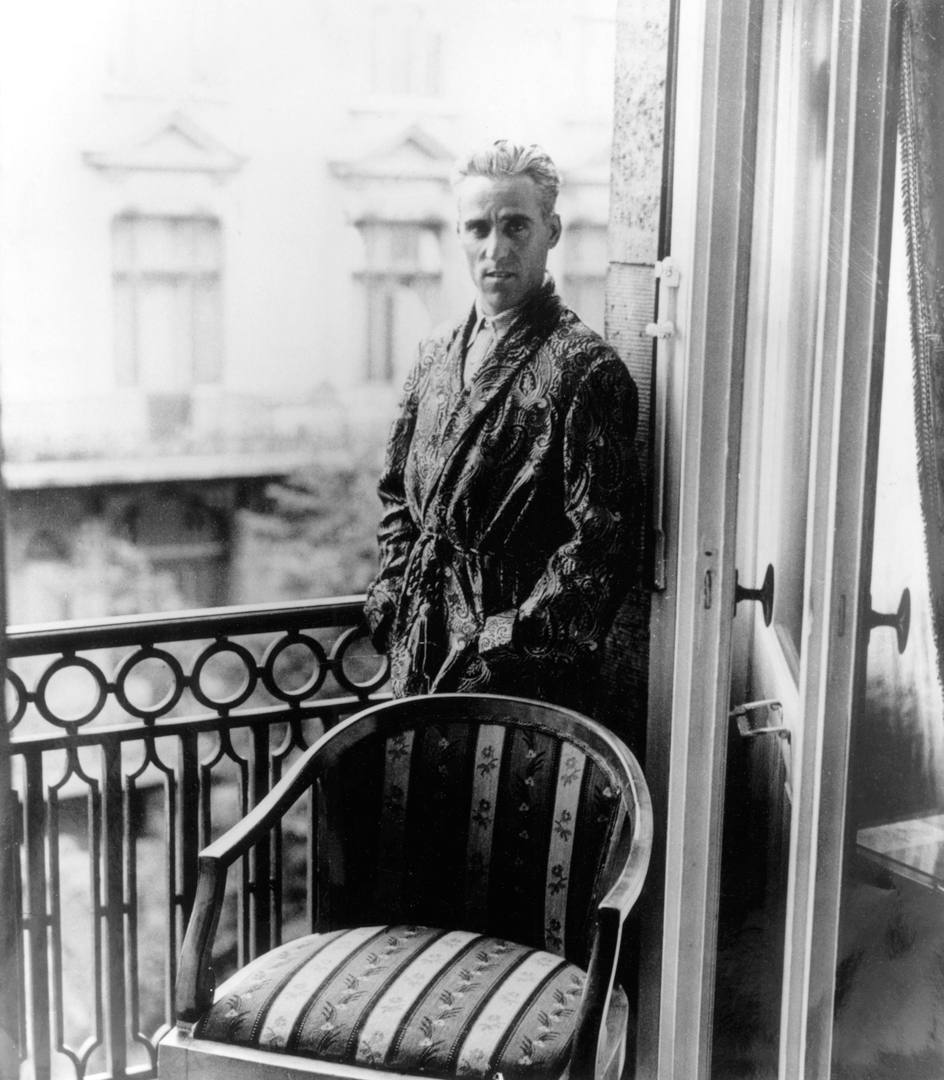

In the first of a two-part series, Robert Newman explores the amazing life and career of “The Flying Mantuan” – Tazio Nuvolari

Warm sun, drivers in short-sleeved shirts, jacketless officials, some spectators in shorts: the amiable warmth of midsummer had already eased its way over to Mantua, northern Italy. It was June 13, 1948, a special day in the life of the ancient walled town. The cream of Italian motor racing was there as a mark of respect for Tazio Nuvolari, the man they called il maestro, the master, to compete for a trophy he had donated. It was the day of the Coppa Alberto and Giorgio Nuvolari, a race organized by the Auto Club of Mantua of which Tazio was president, and named after Nuvolari’s two sons, Giorgio who died of myocardial infarction in 1937, and Alberto who succumbed to nephritis 10 years later.

Photo: Alfa Romeo Archive

It was also the day on which Nuvolari put his thoughts into words and admitted to himself and his old friend and rival, Achille Varzi, that he was definitely going to retire.

The entry for the race befitted the occasion: Alberto Ascari, Felice Bonetto, Gigi Villoresi, Achille Varzi, Franco Cortese and, of course, the boys’ father Tazio Nuvolari, who was slowly dying. His heart was weakening and the great volumes of exhaust fumes he had inhaled since his first race 28 years earlier were destroying his lungs. He did not want to give up racing and was still highly competitive, as he had shown in the Mille Miglia the previous month: he had built up an astounding 30-minute lead before his disintegrating Ferrari 166 S finally expired. But illness was forcing his hand, at a time when his popularity had never been greater.

His popularity had been earned on the battlefield, racing with extreme determination, daring, ruthlessness and talent: a wealth of motor racing talent that enabled the little Italian to beat his contemporaries almost at will – among them Campari, Varzi, Taruffi, Stuck, Caracciola, Rosemeyer, Farina and Ascari. Tazio liked many of his opponents and often invited them home to dinner: but after they had gone, he remarked more than once to his wife Carolina, “ I like him and I’m sorry I’ll have to beat him in the race.”

His popularity had been earned on the battlefield, racing with extreme determination, daring, ruthlessness and talent: a wealth of motor racing talent that enabled the little Italian to beat his contemporaries almost at will – among them Campari, Varzi, Taruffi, Stuck, Caracciola, Rosemeyer, Farina and Ascari. Tazio liked many of his opponents and often invited them home to dinner: but after they had gone, he remarked more than once to his wife Carolina, “ I like him and I’m sorry I’ll have to beat him in the race.”

Tazio Nuvolari’s racing career was as distinguished as it was unique: 124 motorcycle races, 39 victories, 39 class wins, 40 fastest laps. His performance in cars was even more spectacular: 229 races, 66 victories (including 16 Grands Prix, two Mille Miglias, two Targa Florios, two Tourist Trophies and America’s Vanderbilt Cup), 38 class wins, 50 fastest laps.

These statistics confirm the Flying Mantuan’s achievement, but not why a small man of 5ft 5ins tall, who weighed just 130 lbs, was so successful. His success stemmed from the fact that he always raced on the limit, his small physique taking the big powerful monsters of the day by the scruff of the neck and making them do what he wanted.

Tazio’s determination cost him dearly – a total of 14 accidents, nigh on amputation of his left leg, severe burns to his face and body, innumerable broken bones, a fractured spine and, eventually, his life. But it was also the key to his superiority. He once said in an interview, “I’ll do anything to win a race. I waste no time with being sporting. Win first and let them lodge their objections afterwards, that’s my motto.”

An idea perhaps less than simpatico, but the mindset of the man considered by many to be the greatest racing driver of them all, regardless of the usual bickering about not being able to compare drivers of different eras who raced such totally different cars.

Varzi, who was also an Italian motorcycle champion, first met Nuvolari at the Circuit of Parma bike race on May 20, 1923, when Tazio won the 350 cc event. Achille was 19 years old and Nuvolari 30. They became friends and raced Bugatti 35 C’s together in Tazio’s own Scuderia in 1928, but later an inevitable rivalry developed between them that was mightily inflated by the press: an overstated tug-of-war they sometimes played up to and that soon divided Italy into two camps, Nuvolari and Varzi. If you loved one, you had to hate the other.

Nuvolari and Varzi were the Senna and Prost of their day: men who won just about everything motor racing had to offer. Varzi’s tally did not lag far behind Tazio’s: he won three Italian national championships in cars, 16 Grands Prix, 15 Italian national races, the Targa Florio twice and the 1934 Mille Miglia.

Photo: Alfa Romeo Archive

Theirs was more of a love than a hate relationship. Certainly, they were at each other’s throats in their racecars, but away from the track, they were friends, even if there was a smouldering antagonism just below the surface.

Silly stories abounded about the two, probably the most ubiquitous of which had Nuvolari robbing Varzi of victory in the 1930 Mille Miglia. There were even reports of the two having a blazing row in Brescia after the race, at the end of which Varzi is supposed to have slapped Tazio’s face.

But if there was animosity between them, it did not show at the 1948 Coppa Alberto and Giorgio Nuvolari. There, they came face to face and stared at each other knowingly for a moment, neither saying a word, until Nuvolari broke the ice.

“I’ve finished,” he said simply. He meant he was going to retire for good: he knew he could not go on for much longer.

“Me, too,” said Varzi.

They both wanted out for different reasons: Nuvolari so that he could stop half-suffocating himself in open racing cars that gave no protection from those insidious exhaust fumes; Varzi because he had kicked a destructive morphine addiction, freed himself of a ruinous love affair with a beautiful German woman and married his patient hometown fiancée, Norma: he wanted to enjoy what was left of his life.

The huge crowd in Mantua cheered as Nuvolari shot into the lead at the start of the race in the summer of ’48, and hollered themselves hoarse as he stayed in front in his Ferrari 125 S for eight laps. But then the inevitable happened, as Tazio coughed and retched in clouds of fumes, he was forced to retire. The winner was Bonetto in one of Piero Dusio’s Cisitalia D 46 4Cs; Cortese came second in a Ferrari 166 F2 and Varzi third in another Cisitalia.

At the end of the race, the two great champions said their goodbyes and, after a second’s hesitation, they embraced.

Photo: Alfa Romeo Archive

Nineteen days later Achille Varzi was dead, killed practicing in the rain for the Grand Prix of Switzerland at Bremgarten. His Alfa Romeo 158 went straight on at the entrance to a corner, jerked violently, spun twice and slowly overturned into a ditch. Achille died instantly from head injuries. Nuvolari’s tormented life continued for another five years.

As the weeks and months dragged on, Tazio’s lungs got worse. But still he raced four more times after the ’48 Coppa Alberto and Giorgio Nuvolari, always taking command of each event before horrendous fits of coughing and vomiting forced him to retire. Nuvolari managed to finish just one of those last four races: he won his class and came 5th overall in a Scuderia Abarth Cisitalia-Abarth 204A on the island of Sicily in the 1950 Palermo-Monte Pellegrino hillclimb, a form of motor sport he never really liked.

That was the end of Tazio’s outstanding career. All he had left was his devoted wife Carolina, a legion of fans for whom he could no longer race, his memories and his photographs, which he occasionally took out and studied. Later, when he was confined to bed with his ailing lungs, a weak heart and a paralyzed arm – which he detested most of all – he could no longer reach for the pictures himself, so he would have his nurse bring them to him. He would lay them out on his bed, look at them and remember. They recorded a lifetime of unique talent, victory and achievement that was so outstanding, so glorious that many still say, almost 50 years after his death, that no other racing driver, Fangio, Clark, Senna and Prost included, ever equalled it.

Tazio Giorgio Nuvolari was born at 9 a.m. on a frosty November 16, 1892, in the small village of Castel d’Ario, near Mantua, Italy. He was the fourth child of farmer and landowner Arturo Nuvolari and Emma Zorzi. Arturo and his brother Giuseppe loved bicycle racing and Uncle Giuseppe had talent: he won the Italian national championship and Tazio idolized him for it. Giuseppe gave the boy a bicycle for his sixth birthday and taught him how to ride it. He taught the lad something else, too: to be competitive.

Tazio had his first taste of motor racing in 1904, when Uncle Giuseppe took him to see Vincenzo Lancia win the nearby Circuit of Brescia in a Fiat. That was when the young Nuvolari fell in love with speed. But he was not able to do much about it for a while, as he was soon to begin studying to become a surveyor at the Technical Institute of Mantua.

In 1912 Tazio fell in love again, this time with the beautiful Carolina Rosa Perini, whom he met at a dance before he was called up for his obligatory military service.

He came back to Mantua after a year of soldiering and in 1914 drove his first car, Uncle Giuseppe’s 75 hp SCAT. In 1915, Tazio applied for and was granted his first racing license, for motorcycles, but Italy’s entry into the First World War meant that, before he could use it, he was called up again. At the time, few Italians could drive, so Nuvolari was made a Red Cross ambulance driver. His job was to take the wounded from the front line at night, with his Fiat ambulance’s lights switched off, to rear echelon field hospitals. One night, as the ambulance squelched down a muddy track in the dark, the vehicle slithered off the track and ended up in a ditch.

Photo: Alfa Romeo Archive

A wounded colonel Nuvolari was carrying asked gruffly, “What’s your name?”

“Tazio Nuvolari, sir.”

“Take my advice, boy, because I know what I’m talking about,” the colonel growled, “Stop this driving. You’re no good at it.”

“No, sir,” Tazio said sheepishly.

Nuvolari was discharged in 1915, after which he and Carolina were married and went to live in Milan. Giorgio was born a year later, on September 14.

It was not until June 1920, at the age of 27, that Tazio competed in his first race. It was the 120-mile International Circuit of Cremona, but his 600 cc Della Ferrera motorcycle did not last the distance and he retired with mechanical problems. A year later, Nuvolari competed in four car races and on March 20 he triumphed for the first time: it was in the Verona Cup, a 170-mile regularity race, which Tazio won in an Ansaldo Tipo 4 at an average speed of 24.68 mph.

In 1922, the Nuvolaris moved back to Castel d’Ario and Tazio opened his own car dealership, Automobili Nuvolari Tazio Castel d’Ario. He sold SCAT, Lancia, Bianchi and Alfa Romeo as well as motorbikes, but a career in business was not for him and he continued racing motorcycles. That year Tazio competed in four races and came second in one, retired from two and, on November 5, won the Riunione Motorciclistica at Mantua on a 1000 cc Harley Davidson, his first motorcycle victory.

In 1925, Nuvolari was invited by Alfa Romeo to take part in a racing car test session at Monza, where he and other hopefuls showed what they could do. It was Tazio who shocked the test organizers: he clocked a fastest time of 3 minutes 36 seconds at an average 104 mph in their Alfa P2. That beat Portello works driver Giuseppe Campari’s time and came within two seconds of Alfa star Antonio Ascari’s fastest lap. On his sixth and last lap in the P2, Nuvolari crashed and was severely bruised. Twelve days later, he had to race at Monza again, this time on a motorcycle. On race day, he was still in great pain but had his doctor encase him in a rigid bandage corset in his stooped bike riding position, padded his body with felt and won the 350 cc race on his Bianchi!

In 1926, Nuvolari only raced bikes. He competed in 27 events with the Bianchi, won 12, scored seven class wins and eight fastest laps.

It was in 1927 that Nuvolari began a gradual switch to cars and reduced his motorcycle commitments to 12 races, of which he won four. Tazio competed in the first-ever Mille Miglia driving an uncompetitive Bianchi Tipo 20 Sport into a creditable 10th overall, but won his first car race of the year, the Grand Prix of Rome, in a Bugatti Tipo 35.

He moved on to full-time car racing in 1928 by forming his own Scuderia Nuvolari, for which he bought four Bugatti 35 C Grand Prix cars, sold one to Achille Varzi and another to Cesare Pastore, with both of whom he created his squadra.

Photo: Alfa Romeo Archive

Nuvolari’s second son, Alberto, was born on March 2, 1928 and on the 11th Tazio won his first international car race, the Grand Prix of Tripoli, in which his Scuderia’s Bugattis dominated. That year, Nuvolari competed in a total of 11 races, won two, won his class once, set four fastest laps and was runner-up to Giuseppe Campari in the Italian national championship. Nuvolari was beginning to make his mark.

The following year was a bleak one for Tazio in cars, of which he raced a variety – Bugatti, OM, Alfa Romeo and Talbot, only winning one out of nine events.

But in 1930 he became a star. He joined Scuderia Ferrari, a team that prepared and raced works Alfa Romeos, and won the “Big One” right out of the box – the Mille Miglia.

Varzi and Nuvolari were driving Alfa 6C 1750 Zagatos in the Brescia-Rome-Brescia classic and had been constantly swapping the lead in an exciting race. Legend has it that Alfa Romeo ordered both to slow down on the last leg. It looked like Alfa had the race in the bag and its executives saw no reason why they should lose it just because their two drivers might decide to slug it out in a final dash to the chequered flag. But while Varzi, who was leading, eased the pace on the home run into Brescia, Nuvolari put his foot down and gobbled up his teammate’s 10-minute lead. According to Nuvolari’s co-driver, Giovanni Battista Guidotti, Tazio switched off his Alfa’s telltale three headlamps so that Varzi could not see him coming up behind, quietly catching his rival. Nuvolari won by 20 minutes, with an enraged Varzi second. That is why they are supposed to have had their heated argument in Brescia, even if post race photographs show that all seemed sweetness and light between them.

The truth, however, is somewhat different. Before the alleged incident, Varzi had been leading the race by 10 minutes but Nuvolari was chipping away at his lead and had no need to resort to such subterfuge. Achille himself said that, as soon as he saw Nuvolari’s headlamps, he decided not to resist any longer, as he knew he had lost most of his 10-minute advantage. Nuvolari overtook Varzi near Peschiera at about 5:20 a.m. as the sun was coming up, so there would have been no point in Tazio switching off his headlamps. His car could clearly be seen by Varzi, who asked his riding mechanic, Carlo Canavesi, “Is it him?” The co-driver spun around in his seat, saw the unmistakable three headlights of Nuvolari’s 1750 Zagato and confirmed it was the Flying Mantuan.

Tazio’s other big victory of the year was at Ards in Ireland’s Tourist Trophy, in which Giuseppe Campari came 2nd and Varzi 3rd, all of them in Alfa 1750s.

By that time, Nuvolari was so popular in Italy that the first of a vast number of books was published about him. It was also the year Giorgio Nuvolari, just 12, learned to drive a car. A champion of the future? No one will ever know. Certainly, the interest was there. Giorgio spent much of his time accompanying his father to races and often wore driver’s overalls in the pits as he talked racing with other star drivers of the day.

In 1931, Nuvolari competed in 20 races, 19 with Alfas and one with a Bugatti. He won seven times, including his first Targa Florio and the Grand Prix of Italy, coming 4th in the International Championship. He had become such an impressive driver that fellow racer Luigi Arcangeli said of him, “Tazio? They say he goes like the devil. Those who saw him at the Targa Florio today must change their opinion. The man drives like a god.”

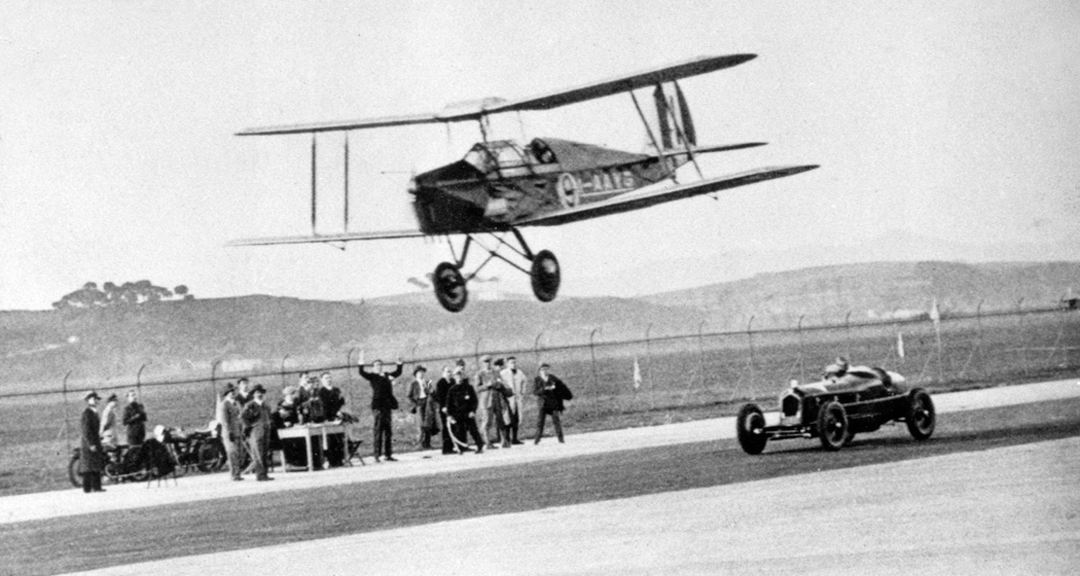

At the end of the year, Nuvolari sealed his national popularity by racing an aeroplane – a Caproni 100 flown by a Commander Suster – in his Alfa 8C 2300 at Lottario near Rome. If he had not known he was Italy’s best-loved sportsman before that oddball event, he had no doubt after it. He lost by a few measly yards, but the incongruity and daredevil cheekiness of it all caused a huge stir and generated acres of press coverage.

Photo: Pirelli

The following year was an outstanding one for Nuvolari. He won seven races including the Grands Prix of Monaco, Italy, France, the Targa Florio again, the Ciano and Acerbo Cups. Italy was at his feet. Gabrielle D’Annunzio, superstar dramatist, poet and commander of his own private army, invited the little driver to lunch and wrote a new chapter in the Nuvolari book of folklore. He gave Tazio a small gold tortoise with the dedication, “To the fastest man in the world, the slowest animal.” Loving the irony of it all, Nuvolari added his intersected ‘TN’ initials to the animal’s back and adopted the gold tortoise as his trademark. He raced with one pinned to his shirt, wore gold tortoise lapel pins, had the little animal printed on his personal stationery, embroidered on his overalls, painted on the fuselage of his aeroplane and it appeared with him in millions of press pictures across the world, eventually becoming almost as famous as its owner.

As far as family life went, 1932 was a happy year for Tazio. His wife Carolina adored him; his sons Giorgio and Alberto admired him and wanted to become racing drivers like him. And the minute he left his house in Castel d’Ario, it seemed like the whole world was outside waiting to applaud him. Every day brought an avalanche of fan mail: letters even arrived from overseas; some just addressed to ‘Nuvolari, Italy.’

Tazio’s victories were now so frequent they were no longer news to some. One Italian sports paper ran the headline ‘Nothing New’ over its story of how Nuvolari won the Grand Prix of Reims in 1932, the year Tazio won the International Championship and his first Italian national title.

Everyone loves a winner, especially politicians. Italy’s dictator Benito Mussolini, decided it was time to bask in a little of Nuvolari’s reflected glory. So Il Duce invited the driver to his residence in Rome and asked Tazio to bring along his Alfa Romeo P3. Sitting in the car in the grounds of his official residence, Mussolini looked up from the controls and said to his entourage, “Here is an Italian who should be an inspiration to the nation for all his courage and daring.” That, naturally, provoked some newspapers into accusing Nuvolari of being a Fascist, although in truth he was apolitical.

Twenty-one races, 11 victories. The little Mantuan and his gold tortoise logged a 52% success rate in 1933, the year of the Tripoli Grand Prix scandal. Their wins included the Grands Prix of Tunis and Nimes, the 24 Hours of Le Mans with a young Raymond Sommer and the Mille Miglia with his mechanic, friend and fellow Mantuan, Decimo Compagnoni, all in Scuderia Ferrari Alfas.

But Nuvolari was not a happy man: he entered the Grand Prix of Belgium with his own Maserati 8CM, prepared by Decimo, and won. It was the Maserati victory that brought the whole thing to a head. Enzo Ferrari was beside himself that his star driver should compete, let alone win, in one of the opposition’s cars. They had an almighty row, in which Tazio accused Ferrari of providing him with inferior material and, well aware of his ever-growing popularity and success, not paying him enough. Such was his public notoriety that he even demanded Scuderia Ferrari’s name be changed to Scuderia Nuvolari, although he would probably have settled for Scuderia Ferrari-Nuvolari.

Naturally, Ferrari would have none of it, so Tazio left the team and set up on his own again, this time with the Maserati and Compagnoni. He showed Ferrari he could go it alone, too: he won the Grand Prix of Nice and the Ciano Cup in his Maserati 8CM and the Tourist Trophy again, but this time with Alec Hounslow in an MG K3 Magnette. Three weeks later, though, Tazio crashed. It was in the Grand Prix of San Sebastian at Lasarte, Spain, where he lost the rear end of the Maserati at 90 mph: the car smashed into a milestone and then a bridge. Nuvolari was thrown out and ended up with head and leg injuries that would keep him out of racing for the rest of the season.

Photo: Maserati

Tazio continued to run his own team in 1934 and drove a hodge-podge of cars, including the Maserati, a Bugatti 59S and various Alfa Romeos, with little success: in 20 races he won twice and retired nine times. That was the year Achille Varzi took revenge for Tazio’s 1930 Mille Miglia win. Nuvolari was in a 2300 cc Alfa specially prepared by Portello’s technical boss, Vittorio Jano, and Varzi was in an Alfa 2600 cc whose engine was modified by Jano – and tweaked even more by Scuderia Ferrari. Again, the two swapped the lead in an enthralling contest that mesmerized Italy. Nuvolari was two minutes ahead by the time an edgy Varzi got to Scuderia Ferrari’s Imola service area, where the Commendatore had a new set of extra-deeply grooved tires ready for his car. But the weather was good and Varzi told Ferrari he saw no reason to be slowed down by hand-cut rain tires. Ferrari said he had telephoned ahead and discovered that it was raining farther north. Varzi exploded and the two had a fearsome argument, before Achille stomped off saying to Ferrari, “You do as you like.”

The rain tires were fitted, it did rain on the last leg of the race and Varzi beat Nuvolari to take revenge after losing the hotly contested 1930 Mille Miglia.

Then, disaster: Tazio had the most serious accident of his career in the minor Circuito di Bordino at Alessandria, Italy. It was raining and while overtaking textile millionaire Count Carlo Felice Trossi, Nuvolari’s Maserati skidded unexpectedly, zigzagged violently, rolled and smashed into a tree. Tazio was thrown out of his car again and lay stunned and injured on the track, but he was lucid enough to realise Varzi was bearing down on him in an Alfa P3 at about 90 mph: Achille would have inadvertently killed Nuvolari had the little Italian not managed to painfully wriggle his way on to the grass verge, where he passed out.

Tazio woke up in hospital screaming with pain: his left leg had been shattered. One of the doctors told his wife Carolina that they could either amputate the leg or treat it and risk infection, but she had to decide quickly. The thought of Tazio condemned to a wheelchair for the rest of his days would be a living nightmare for both of them, she thought, so she withheld permission to amputate – and Nuvolari’s leg mended in a month, without infection.

Tazio was fed up. He had had his leg in plaster for four weeks and could not stand his immobility any longer. He told Compagnoni they were leaving for the race at Avus, near Berlin.

“As spectators?” Compagnoni asked.

“Spectators? We’re going to race. Get the Maserati ready,” he told his mechanic.