In the last of a two-part series, Robert Newman explores the amazing life and career of “The Flying Mantuan” – Tazio Nuvolari

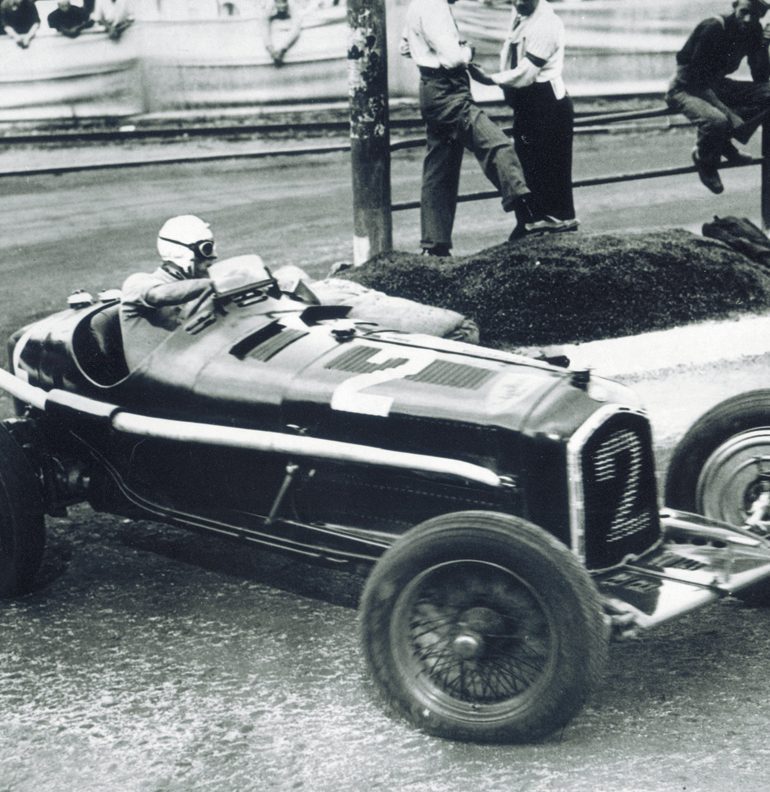

In 1930, Nuvolari had the most serious accident of his career in the minor Circuito di Bordino at Alessandria, Italy. It was raining and while overtaking textile millionaire Count Carlo Felice Trossi, Nuvolari’s Maserati skidded unexpectedly, zigzagged violently, rolled and smashed into a tree. Tazio was thrown out of his car yet again and lay stunned and injured on the track. Fortunately, he was lucid enough to realize Varzi was bearing down on him in an Alfa P3 at about 90 mph: Achille would have inadvertently killed Nuvolari had the little Italian not managed to painfully wriggle his way on to the grass verge, where he passed out.

Tazio woke up in the hospital screaming with pain: His left leg had been shattered. One of the doctors told his wife Carolina that they could either amputate the leg or treat it and risk infection, but she had to decide quickly. The thought of Tazio condemned to a wheelchair for the rest of his days would be a living nightmare for both of them, she thought, so she withheld permission to amputate – and Nuvolari’s leg mended in a month, without infection.

Tazio was fed up. He had had his leg in plaster for four weeks and could not stand his immobility any longer. He told his mechanic, Compagnoni, they were leaving for the race at Avus, near Berlin.

“As spectators?” Compagnoni asked.

“Spectators? We’re going to race. Get the Maserati ready,” he told his mechanic.

Decimo rigged up a leather stirrup in the Maserati’s cockpit for Tazio’s plaster-clad left leg and off they went to the high-speed Avus circuit, where Nuvolari blustered his way past the officials and into the race. He operated all three of the car’s pedals with his right foot, the other leg painfully suspended from Compagnoni’s stirrup, and finished 5th.

Nuvolari won races in Naples and Modena with great authority that year. Still at knives drawn with Scuderia Ferrari and its choleric boss, when Tazio won the Commendatore’s hometown race in a Maserati 6C 34, he sent a bale of straw to an infuriated Enzo Ferrari with a note saying, “For your horses.”

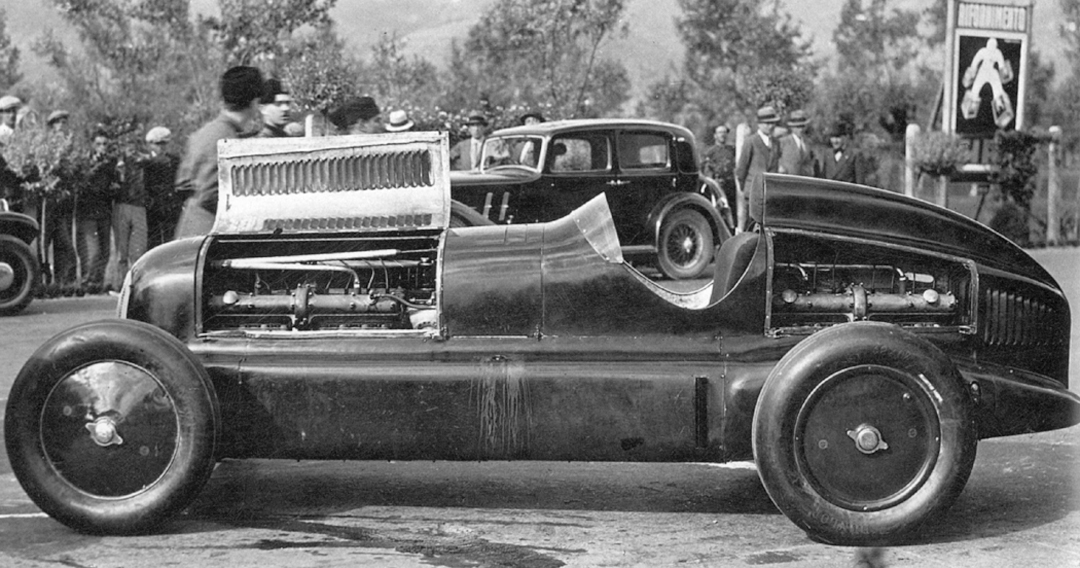

The following year the two made up and Tazio was back racing for Scuderia Ferrari. He won with the Alfa Romeo P3 at Pau, Biella and Bergamo and tested the new twin-engined Alfa Bi-motore, which had one eight-cylinder 3165 cc engine up front and another in the tail. He even broke Panhard’s two international speed records with the car, recording an average 199.767 mph for the standing kilometer and 208.981 mph for the standing mile, on the freeway between Florence and the coast.

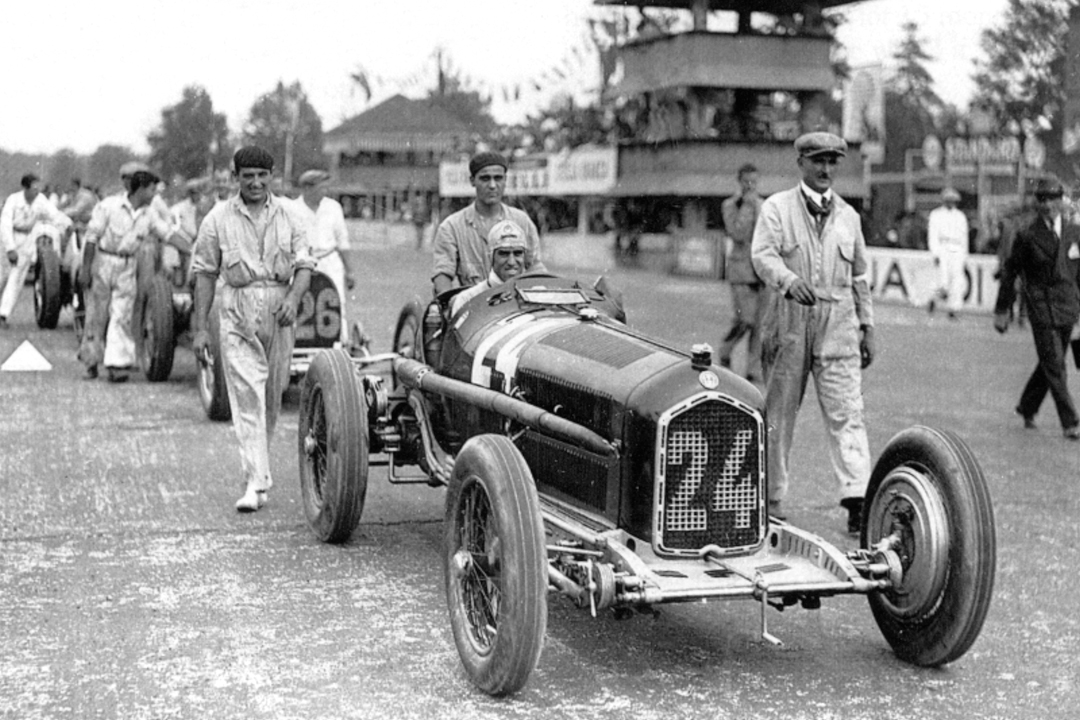

By this time, the team’s Alfa Romeo B P3 was becoming rather long in the tooth and the Bi-motore was no racecar. The scions of Nazi Germany, Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union, were cleaning up with their superior government-subsidized technology. Except at their own Grand Prix. In probably his greatest race, Tazio beat the all-conquering Silver Arrows and the likes of Caracciola, von Brauchitsch, Lang, Varzi, Stuck and Rosemeyer in his obsolete P3.

It was drizzling as the competitors in the 1935 Grand Prix of Germany were flagged away at the daunting Nürburgring. Der Regenmeister, Rudolf Caracciola, immediately loud pedalled his 430 hp Mercedes-Benz into the lead, followed by Nuvolari in his pitifully underpowered 215 hp P3, Luigi Fagioli in another Mercedes, Bernd Rosemeyer in an Auto Union and the Mercedes of Manfred von Brauchitsch. By the sixth lap, Alfa Romeo’s Louis Chiron, Antonio Brivio and Carlo Castelbarco had all dropped out. Nuvolari in 4th was Italy’s only Italian standard-bearer in his ageing car and he whipped the P3 hard to keep up with the intimidating Mercedes. Surprisingly, the Auto Unions were about as badly off as the Alfas, with only Rosemeyer left in the hunt.

It had stopped raining by the 11th lap so Tazio risked more speed and overtook von Brauchitsch, Fagioli and even the Regenmeister himself to go into the lead. The wily little Italian was gaining tenths of a second on many of the Nürburgring’s 174 corners in that old car.

Tazio pitted first, followed by Caracciola, von Brauchitsch and Rosemeyer in that order. After taking on more fuel and tires, all the Germans shot off again in short shrift, but Nuvolari was left languishing in the pits for 70 long seconds because the Scuderia Ferrari mechanics had broken the lever that worked their petrol pump. The little Mantuan was furious, but he took his rage out on the track, not the mechanics. Tazio rejoined the race a distant 4th, only to find Rosemeyer in the pits with mechanical problems next time around. Caracciola’s Mercedes was flagging, as well, as the old red Alfa, driven by that 5 ft-5 inch genius, passed him on lap 15 and gave chase to von Brauchitsch.

The von Brauchitsch Mercedes was in good shape, but the German was not treating it well. He was pushing the W25 too hard and stripping his tires of their tread in his rush to outdistance Nuvolari. Tazio saw and understood the Mercedes pit signals telling their race leader to come in for more tires and pushed his P3 even harder. He had been a minute behind the German nobleman after their pit stop on lap 11, but by the 18th he had chopped that down to 37 seconds.

Von Brauchitsch decided not to pit for new tires, as he would surely lose the race. Instead, he gambled on his existing Continentals lasting to the finish, but antagonized his tires even more by setting the race’s fastest lap of 80.53 mph. At the start of the last 14.17-mile lap, Nuvolari was 30 seconds down on the German, so von Brauchitsch thought he could make it and win for the Fatherland. Wrong. Soon afterward, his car’s handling began to tell him different – his tires were down to the canvas. Not that the crowd knew anything about it; they thought their man would teach the Italian and his obsolete car a thing or two and give them a sound thrashing.

In the pits the rotund Mercedes team boss, Alfred Neubauer, began to suspect something was up: von Brauchitsch was overdue. Neubauer’s suspicions were confirmed by the sound he heard in the distance: It definitely was not the shrill howl of a Mercedes-Benz W25, but the guttural rumble of an Alfa Romeo Tipo B P3.

One of von Brauchitsch’s tires had deflated on the Karussel and Tazio had leapt on him in an instant, relishing the reliability of his old car. That far-off engine note became a mighty roar as Nuvolari powered his P3 across the finish line, to the stunned silence and incredulity of the beswastikaed Nazi party officials and thousands of German spectators.

So much had a German been expected to win that officials at the prize-giving ceremony were all of a fluster: They could not find a recording of the Italian national anthem, which eventually blared out of the loudspeakers after an extremely pregnant silence.

Photo: Alfa Romeo Archive

The huge diameter winner’s laurel wreath was obviously meant for a statuesque Teutonic frame, for it was almost as tall as Nuvolari. The Italian victor winced as the weighty garland cut into his left shoulder during his country’s anthem after a race that was a masterpiece of ability, sensitivity, maturity and craftsmanship.

In all, Tazio competed in 22 races in 1935, won 10, took two class wins, set 10 fastest laps and became Italian national champion for the second time. At 43, he was at the height of his powers and was idolized by racing fans the world over. His home was filled with trophies, plaques, medallions and decorations of all sorts. Signed photographs of the rich and powerful – Benito Mussolini, Prince (later King) Umberto of Italy, Britain’s Duke of Kent, King Vittorio Emmanuelle, the Grand Duke of Monaco, poet and playwright Gabriele D’Annunzio – adorned his office.

And wherever he went, beautiful women surrounded him. Years later, his wife Carolina would say in an interview, “I travelled a lot with my husband. In every country, in every city people recognized him. Beautiful women became infatuated with him and tried in every way to attract his attention. But Tazio only really loved me. Ours was a tempestuous love, but at the same time a silent, tranquil one. To everyone else, he was a great champion: To me, he was a great man who suffered very much.”

Especially when his son Giorgio died at the age of 18 in 1937. Nuvolari adored his handsome son, who had grown to be five inches taller than his father, square-chinned and had a smile that gave the girls butterflies. Tazio bought Giorgio a motorbike and chuckled quietly to himself when the lad was fined for exceeding the speed limit on the machine.

But while Giorgio was attending a Swiss college to improve his French and German, he fell ill after sweating profusely while playing tennis and football. The boy caught a serious cold that grew into something worse. Doctors diagnosed – accurately – myocardial infarction, the destruction of an area of heart muscle as a result of an occlusion of a coronary artery.

Tazio and Carolina were called to the college and told of the boy’s illness – and that it was fatal. The great champion and his wife wept, unable to believe their vibrant young son would be taken from them.

They resolved to get Giorgio home as quickly as possible. Tazio’s fame was such that nobody would deny him anything, and he was able to arrange a train for their exclusive use to take them straight back to Mantua non-stop.

Weakened by the journey even so, Giorgio lay immobile in his bed as his father came to say goodbye.

“Dad, I want to live,” Giorgio cried, desperately embracing Tazio.

“You are a Nuvolari, you must live,” Tazio replied and then told the boy his next race was the Vanderbilt Cup in America.

“I’ll bring you back the cup, but you must get well again,” he told his son.

But Giorgio worsened and Tazio did not want to leave. It was Carolina who persuaded him to go, promising to keep him informed of the boy’s condition.

Photo: Maserati

The Alfa Romeo team – Nuvolari, Antonio Brivio and a young Giuseppe Farina – travelled to the U.S. aboard the passenger liner Rex. When the ship docked in New York harbor, a rich Italo-American was among the people interviewed by the press and he said, “Certainly, if the Italians could win the Vanderbilt Cup that would be a real success. Caruso, Valentino and ‘O Sole Mio’ are OK, but success like that would be something else again. The United States would admire Italy.”

He got his wish, but not before the local Mafia got to Nuvolari. Two gangsters who had bet $50,000 on another driver approached Tazio before the race and threatened to kill him if he won. But, courageously, the little Mantuan told them he was not interested in their business affairs and walked off. He won the race and lived to tell the tale.

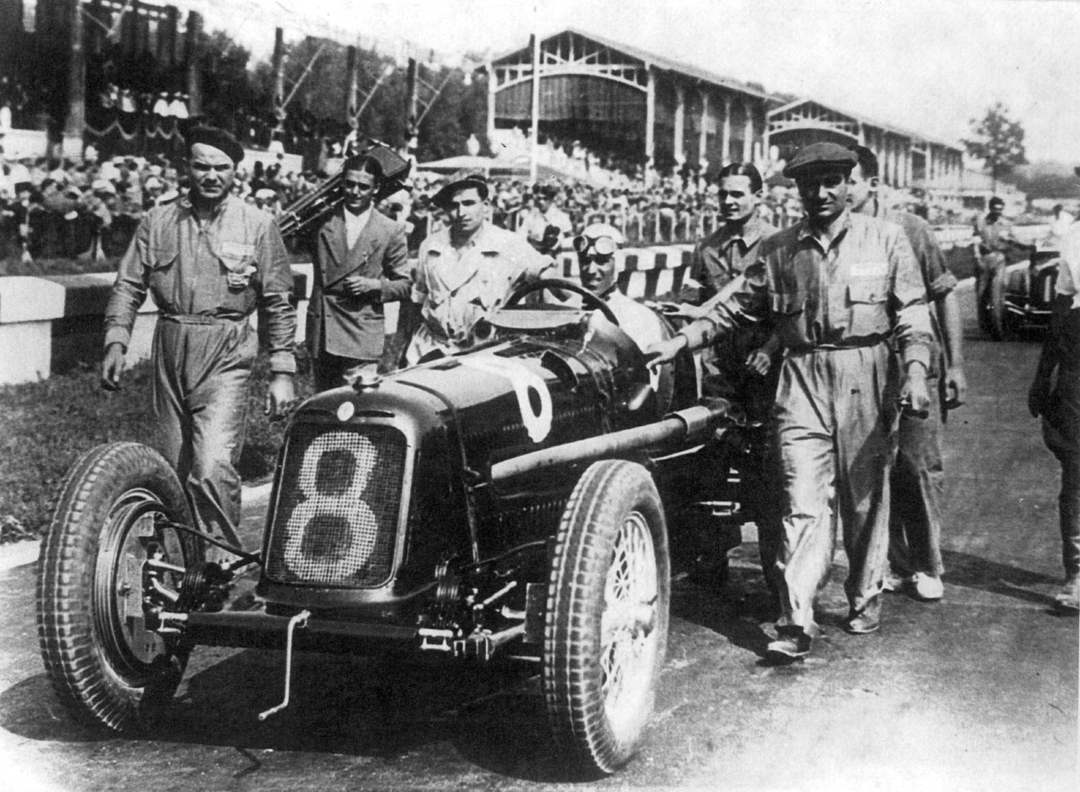

At the Roosevelt Field dirt track on Long Island, Brivio shot into the lead in his Alfa Romeo 12C 36 with Nuvolari and a sister Alfa in hot pursuit, but that did not last long. Tazio took Tonino on the straight after a spectacular tussle and by the 12th lap, Nuvolari led Brivio by 12 seconds, the American Winn by 27, Farina in the third Alfa by 52 and Jean-Pierre Wimille in a Bugatti 4900 by one minute and 12 seconds. After 18 laps, Farina managed to slip into 3rd place, but later went off.

Even a booming loudspeaker system offering $1,000 and later another $500 to any American driver who managed to overtake Nuvolari and stay in front of him for a lap had no effect: The little Mantuan kept the lead, in spite of having to pit for a change of plugs. After more than four hours of racing, Tazio was first across the finish line at an average 65.947 mph, having also set a fastest lap of 69.934 mph. Second was Wimille 12 minutes behind, 3rd Brivio at 13 minutes, 4th Raymond Sommer at 14 minutes and Mauri Rose 5th.

Nuvolari won $32,000 that day, and took the huge Vanderbilt Trophy home for Giorgio.

Tazio won six of his 13 races in 1936, including the Grands Prix of Hungary and Spain, and became the Italian national champion for a third time. But he also had another of his high-speed accidents. A tire blew on his Alfa Romeo 12C 36 as he practiced for the Grand Prix of Tripoli and the car flew off the track at 125 mph. Badly bruised and with swellings around his spine, Tazio had his painful injuries treated with gentle massage, ice packs and special exercises, so that he could practice again the next day. After that, he declared himself fit to race and came 8th, but the pain was so great he withdrew from the following week’s Grand Prix of Tunis and went home.

Nuvolari’s 1937 was not accident-free, either; his Alfa 12C 36 went off at 60 mph during the Grand Prix of Turin and, as it somersaulted, it threw Tazio out again and he ended up on the asphalt. Doctors diagnosed fractured ribs, severe cuts and bruises to the face and chest, but he did win the Grand Prix of Milan for Alfa nine weeks later, before leaving once again for America and his second Vanderbilt Cup race aboard the liner Normandie.

The trip was the saddest of his life. Decimo Compagnoni awakened him early on June 26 in the mid-Atlantic with a cablegram. Giorgio had died a few hours earlier, calling for his father. “Who knows how he must have searched for me in his mind,” Tazio wrote in reply to his wife’s heart-rending news. Imprisoned on the ship, Nuvolari had no choice but to continue his journey to the States, where he decided he would compete.

Photo: Alfa Romeo Archive

But Tazio’s heart was not in the race; it was with his wife and dead son back in Mantua and, inevitably, his driving lacked its usual attack. Bernd Rosemeyer (Auto Union), Rudolf Caracciola (Mercedes-Benz) and Rex Mays (Alfa Romeo) on the front row led the grid away with Nuvolari following in his Alfa, but he was overtaken a lap later by Dick Seaman (Mercedes). On the 16th lap the engine of the Mantuan’s Alfa 12C 36 lost power and flames started licking out from under it. Tazio leaped onto the driver’s seat and, enveloped in flame, still steered the Alfa toward some trackside straw bales, then jumped out while the car was still on the move. Undeterred, Nuvolari rushed back to the pits, from which he followed the race. In an effort to break the German domination, Tazio took over Nino Farina’s Alfa on lap 34 but returned it to the Turin driver 21 laps later, unable to make the impression he had hoped on the Silver Arrows. Farina eventually drove the car into 5th place.

The race was won by Rosemeyer, with Seaman 2nd and Mays 3rd.

Nuvolari made his sad journey home and, as he embraced Carolina, he cried uncontrollably for Giorgio. His wife told a journalist years later, “It was the first time I had ever seen him cry like that. He forgot he was the fearless Nuvolari, the man who didn’t believe in danger or death. After I reminded him that Giorgio had died calling his name, Tazio locked himself in his study for a long time and refused to speak to anyone.”

There was more bad news to come. On January 27, 1938, Nuvolari was shocked and saddened by the death of his racing soul mate Bernd Rosemeyer. The two were alike in so many ways – super-competitive, ex-motorcycle champions, car racers par excellence – and had become great friends. Tazio was even godfather to Bernd Junior, born on November 12, 1937. But Rosemeyer’s car was knocked off course by crosswinds as he tried to establish a new speed record in a special-bodied Auto Union on the Frankfurt-Darmstadt autobahn. Tazio despaired for Elly Beinhorn, the famous German flier and Rosemeyer’s widow, and did what he could to comfort her in her moment of grief.

On April 8, 1938, Nuvolari suffered yet another accident. His Alfa Romeo 308 burst into flames and, once again, he was forced to leap from the moving car. Tazio was only slightly injured, but was severely shaken and got to thinking about his future. His decision made, he told Alfa Romeo boss Ugo Gobbato that he wanted to retire from motor racing. A few days later, Alfa confirmed Tazio’s decision in a press release that thanked him for his immense contribution to the company and the sport.

But after a holiday in America and a visit to the Indianapolis 500, which he flagged away, Tazio accepted an offer that was just too tempting – it was to take Rosemeyer’s place in the Auto Union team.

Nuvolari came 4th in his first race for the Zwickau company, the Grand Prix of Germany, and brilliantly won the Grands Prix of Italy and Great Britain for them in their 12-cylinder, 2984 cc Type Ds.

In 1939, as Hitler turned up the pressure on Europe and invaded Poland, racing ground to a halt. The first Grand Prix of Belgrade on September 8 turned out to be the last GP for six years – and Nuvolari’s only Auto Union victory of the year. Then it was a forced retirement. Some racing drivers joined the armed forces and were killed during the war. Others, notably Jean-Pierre Wimille, Robert Benoist and Clemente Biondetti, became members of their countries’ resistance in their clandestine fight to rid their homelands of Nazi occupation. In Italy, the Fascists joined the Nazis against the allies and Tazio took Carolina, son Alberto and Compagnoni to the small village of Lanzo d’Intevi, almost 3,000 ft up in the northern Italian mountains, overlooking neutral Switzerland.

There, in a modest little house, Tazio was safe but totally bored. He was not forgotten, though, for in 1942, at the height of the war, he received a letter of congratulations on his 50th birthday from Auto Union, who asked if he would be prepared to drive for them again after the hostilities. Another chance would be a fine thing, he thought, but the war would not cooperate.

Racing cars suffered a checkered fate during the war years. Some Alfa Romeos were hidden in a cheese factory. With the help of the great German champion Rudolf Caracciola, Alfred Neubauer was able to transport his Mercedes-Benz W154s to Caracciola’s villa in Lugano, but the Auto Unions were not so lucky. In 1944, the Russians overran Zwickau: The cars that had survived the bombing were transferred to the USSR. After the war, five eventually came to light, but Auto Union was no more. Nuvolari would never be able to tame their rear-engined monsters again.

By 1945, Tazio had developed a bad cough that signalled the beginning of the end and, a year later, tragedy hit the Nuvolari household once more. On April 11, 1946, Tazio and Carolina’s second son, Alberto, died of nephritis, an illness with its roots in the dysfunction of the kidneys. Like his brother Giorgio, Alberto was just 18 years old.

Nuvolari was destroyed and kept himself to his deserted house, speaking to no one for days on end. But after a month, he threw himself back into racing with all the fervor he could muster – It was the only way he knew of trying to fill the abyss left by the loss of his sons. He drove a Maserati 4CL in the Grand Prix of Marseille on May 12 and was leading the qualifying heat when a piston broke: Humiliatingly, he was not admitted to the final race. Mechanical problems with the Maserati forced him out of the Resistance Cup on the Bois de Boulogne in Paris and the Grand Prix of the Western Freeway in France. His Fiat 1100S expired during the Circuit of Italian Champions at Como and again in the Circuit of Modena, but on July 14 Tazio scored his first post-war victory in the Maserati at the Grand Prix of Pau.

Nuvolari’s car lost a rear wheel during the Circuit of Turin and after leading the first lap of the Brezza Cup, near Turin, in a Cisitalia Tipo D.46 on September 3, his steering wheel broke and he came into the pits brandishing it in his right hand for one of the most famous photographs of his career.

Retirement followed retirement. Nuvolari dropped out of the 1946 Circuit of Milan coughing up blood and was in a bad way when he won the first Giorgio and Alberto Nuvolari Cup in Mantua that year.

In 1947, Tazio, retching and vomiting, almost won the Mille Miglia in a Cisitalia 202-MM, but was relegated to 2nd place by Clemente Biondetti after losing 10 minutes fixing an ignition problem. He later won the sports car category of the Circuit of Forlì and the Circuit of Parma in a Ferrari 125S.

At 56 years of age and seriously ill, Nuvolari still delighted his fans with one of his greatest drives, during the 1948 Mille Miglia in a Ferrari 166S. All of Italy held its breath, spellbound as the great champion led the race into Pescara, his white mask over his nose and mouth, in great pain, coughing up blood and vomiting again. Millions of Italians crowded around radios in bars, shops, offices and homes, willing their hero to win one last time: Others took to the streets in the tens of thousands to see the little fighter charge past. By Rome, Tazio had built up a 12-minute lead, by Livorno 20 minutes and by Florence half an hour, but his car was disintegrating as he went. First, the Ferrari lost a mudguard, then the driver’s seat brackets broke, after which its bonnet worked loose: Nuvolari ripped that off during a service stop and threw it away in disgust, saying something about how much cooler the naked engine would run. The tough little Mantuan raced on over the Futa and Raticosa Passes, into Bologna and on toward Reggio Emilia; but at the village of Villa Ospizio a spring retaining stud broke and the 166’s brakes went: The car had become undriveable.

Wracked with pain and near collapse, Nuvolari walked unsteadily to the village church and asked the priest if he could lie down. Still in full racing gear, he stretched out on the priest’s bed and rested until Enzo Ferrari collected him in a chauffeured car.

A few weeks later, Tazio confided his intention to retire to Achille Varzi at the 1948 Mantua race. He still competed in another four races, but his illness slowly took the upper hand.

Tazio Nuvolari died at his home in Via Rimembranza, Mantua at 6:30 a.m. on August 11, 1953. For his funeral, two days later, his body was dressed, as he had instructed, in his white leather racing helmet, yellow racing shirt with his initials and the gold tortoise on his chest, a ribbon in Italian national colors around his neck, his broad crocodile back-support belt and blue trousers.

The city and province of Mantua declared a day of mourning for his funeral: The blinds of houses, offices and shops were drawn and the cortege extended for miles. Nuvolari’s pallbearers were Alberto Ascari, Pietro Ghersi, Gigi Villoresi, Juan Manuel Fangio, Giovanni Bracco, Gino Valenzano, Renzo Castagneto, Umberto Maglioli and local cycling champion, Learco Guerra.

They laid the master to rest in the Nuvolari family tomb at Mantua cemetery, near the remains of Giorgio and Alberto. Over the entrance to the mausoleum was – and still is – the inscription in Italian: “I will race even faster on the roads of Heaven.”

Special thanks to Pirelli, Alfa Romeo, Fiat, Ferrari and Maserati for their gracious help with this series.

Photo: Fiat