1966 Shelby GT350H

When Ford introduced its new Mustang in 1964, it was an immediate sensation. By itself, it created an entire new class of automobiles. It wasn’t a muscle car, and it wasn’t a sports car; it became known as a “Pony Car.” Still, some called it a “secretary’s car” and criticized its lack of power. That was partially corrected with the high performance 271-hp, 289-cid V8, but there was still a segment of the car buying public that shunned the car. The Pontiac GTO and other muscle cars were attracting those who liked power, and there were many choices for the sports car crowd. Ford wanted those buyers, and they eventually went to a Texan and former race driver who had previously linked performance sports cars, as well as sports car racing, with Ford.

Carroll Shelby

Carroll Shelby was born in Leesburg, Texas, a little town northeast of Dallas, in 1923. His father was a rural mail carrier who developed a love for automobiles when he traded his horse-drawn wagon for an Overland for use on his route. Shelby’s exposure to cars began when he rode with his father on his mail route. In 1930, the family moved to Dallas. No longer a mail carrier, his father still had a car, and he encouraged Shelby’s interest in cars by taking him to the local dirt tracks to watch the racing.

A few years after moving to Dallas, Shelby was diagnosed with a “heart murmur,” but his heart appeared to improve as he grew. At age 14 he learned to drive in a ’34 Dodge. He had little interest in the normal studies in high school, and looked forward to when he could graduate and become more involved with cars or airplanes. High school over, he puzzled over what to do next. He had worked doing deliveries for a local business, but he wanted more. With WWII approaching, he and three friends decided to enlist in the Army Air Force. The recruiter offered them enlistment in the Infantry and to be stationed in the Philippines, but Shelby declined—he wanted the Army Air Force, to learn to fly, and a station in Texas. He finally got what he wanted—partly. After basic, instead of being sent to learn some skills associated with airplanes, he and a buddy were assigned to haul chicken manure from an abandoned chicken farm to the base flower beds. After three months of this, they decided to get out of the detail even if it meant the guardhouse. The trick they pulled on the sergeant in charge of the detail got them five days in the guardhouse, but off the chicken manure detail.

energetic advertising

campaign for the GT350H. Part of the reason may have been that their advertising costs were reimbursed by Shelby American

and Ford.

Shelby’s next assignment was as a fireman at the base airfield. It was better than chicken manure but still boring. Luckily, the Army created a program to train non-commissioned officers to fly—the Flying Sergeants program. Shelby applied, but he had to pass a stringent medical exam. He was tall and thin, and he was ten pounds too light for the program. The solution was to stuff himself with bananas and milk—he passed and entered the program. He passed pre-flight school, but struggled in flight school. In his autobiography, The Cobra Story, Shelby praised his flight instructor for getting him through flight school. He was promoted to sergeant and eventually second lieutenant. He flew a variety of airplanes, including the B-29, but he was assigned as an instructor and test pilot, so he never left the States.

By the end of the war, Shelby had enjoyed all he could stand of the military and got out. A friend suggested that Shelby join him in the trucking business. The home building boom after WWII was going strong, and the friend was hauling redimix concrete to building sites. Shelby got a loan and a truck and started making good money. He even added trucks and was soon hauling lumber as well as concrete. Unfortunately, others were convinced that the construction boom was soon to end, so Shelby sold his trucks to get in the oil business, where he started at the bottom as a roughneck. He found that to be a lot of hard work for very little pay, so he began looking for another career. An aptitude test suggested that he’d be good at raising animals, so he became a chicken rancher—something often mentioned about his past. Raising broilers was very profitable, so there was plenty of money available to borrow to get started. And Shelby made good money at first—20,000 broilers raised and sold and another 20,000 bought. Unfortunately, things didn’t go well this time. The chickens got “limberneck,” more correctly known as Newcastle’s Disease, and they all died. Shelby was bankrupt. It is unfortunate that so many stories about him key on the chicken farming, often referring to him as a “failed chicken rancher” rather than thinking to mention that he served honorably in World War II.

Amidst the uncertainty of this stage of his life, where he tried to keep his family going by working odd jobs, the next and more important stage began. Ed Wilkins, an old friend, had an MG-TC and a home-built special. He asked Shelby if he’d like to try the special at a drag race. Shelby won. Then Wilkins suggested Shelby drive the MG at sports car races in Norman, Oklahoma. Shelby won the MG race, and then he beat a field of Jaguars with the MG. As often happened at amateur races in those days, he was noticed and started getting offers to drive other racecars. He started getting rides in fast cars—Jaguars, Cad-Allards. Success in the Cadillac-powered Allards got him an invitation to race at a 1000-kilometer race in Argentina in January 1954. There was a race within the race for the Kimberly Cup—a challenge race between U.S. and Argentine teams. The U.S. teams were led by Phil Hill, Masten Gregory, Bob Said and Shelby. Shelby’s co-driver was Dale Duncan. None of the U.S. teams did exceptionally well, but neither did the Argentine teams. Shelby and Duncan took the Kimberly Cup with a 10th-place finish. It was a very important race for Shelby, because it got John Wyer’s attention and an invitation to race in Europe. The invitation included no promise of a position with the Aston Martin team, so Shelby would have to pay his own way, at least at first. Money was a constant problem, but he had considerable success racing. He raced in over 150 races between 1952 and 1959. He set land speed records for Austin-Healey, ran F1 races for Scuderia Centro Sud and Aston Martin, and won the 24 Hours of Le Mans with Roy Salvadori in 1959. He crashed hard in the Carrera Panamericana in a Healey and yet still won ten races in 1955 wearing a special fiberglass cast on one arm. Shelby was the Sports Illustrated driver of the year in both 1956 and 1957. He raced with and against some of the best drivers of the 1950s.

Mustang

The Mustang was initially going to be a two-seat, mid-engined sports car, but the experience with the first Thunderbirds, which were two-seaters, had left a bad taste with Ford about two-seaters. Lee Iacocca created a design contest for a four-seat car that could be produced quickly using components already in production. The winning design came out of the Lincoln-Mercury design studio. Most of the parts for the new car came from the Ford Falcon and Fairlane. It allowed the development time to be shortened, and dealers liked that they would not have to stock a lot of unique parts for the car. And the public loved the shape. Ford, especially Iacocca, wanted it to appeal to more people and believed racing was the way to produce that appeal. So, the Sports Car Club of America, SCCA, was approached—actually, it appears that they were told—to make the Mustang eligible for racing in the B Production class where it would compete against Corvettes, Jaguar XKEs, Tigers, small block Cobras and Lotus Elans. SCCA had a simple response; their answer was no! Iacocca was not one to take no for an answer, but he realized that it might take a different approach to get the Mustang into SCCA racing. So he got Shelby to approach his old friend and SCCA President, John Bishop, about running the car in SCCA. It worked. Bishop told Shelby that the Mustang needed to be a two-seater, the car could have either a modified engine or a modified suspension, and there had to be 100 examples built by January 1965 to get the car homologated.

GT350

The challenge was set, and Iacocca wanted Shelby to make it happen. According to Shelby it wasn’t a challenge he was excited about taking: “In 1964, when Lee Iacocca said, ‘Shelby, I want you to make a sports car out of the Mustang,’ the first thing I said was, ‘Lee, you can’t make a race horse out of a mule, I don’t want to do it.’ He said, ‘I didn’t ask you to make it, you work for me.’” With that, it became Shelby’s challenge.

Shelby America Chief Engineer Phil Remington got the job of turning the Mustang into a racecar. He had Chuck Cantwell, Project Engineer, and Ken Miles, Development Consultant, working with him. With a copy of the SCCA General Competition Regulations and a few ideas, they got started. Shelby knew there was no market for 100 Mustang racecars, so they would develop both a racecar and a street car. The decision was made to give both versions the same suspension—Koni shocks on the street cars could be adjusted for racing—but create a hotter engine for the racecar. In October 1964, three ’65 fastbacks were ordered. One would be developed as a street car, and the other two would become the racecar prototypes. Once they had been tested, the remaining cars for the required 100 would be ordered. The cars were ordered in Wimbolden White without wheel covers, seatbelts, rear seat, grille bars and emblem, hood and hood springs. They came with the front fenders from the 6-cylinder Mustang, since those had no badges or holes for badges. For the racecars, even more pieces were deleted: glovebox door, complete interior soft trim, insulation, weather stripping and seals, bumpers, front lower apron, panel, all the glass except for the windshield, and the door channels and winders for the windows.

One area of disagreement was the name for the car. In a meeting including Ford and Shelby American attendees, the name was the topic and a decision seemed unlikely. Shelby, tired of the discussion, recalled “I turned to Phil Remington and asked him what he thought the distance was between the production shop and the race shop. They were in separate buildings. He said, ‘About 350 feet.’ I said, ‘That’s what we’ll call it—the G.T.350.’ And we did.”

Now with a name and the prototypes successfully tested, 100 cars were built for the SCCA inspectors to verify their existence in time for the January 1965 deadline. The G.T.350R was homologated for SCCA B Production. And they were very successful in that class, winning the SCCA National Championship in 1965 (Jerry Titus), 1966 (Walt Hane) and 1967 (Fred Van Beuren). The 1965 G.T.350 was designed to be a racecar that was made streetable, something that didn’t get past reviewers. Car and Driver called the car “loud, rough, scary and dependable.”

In all, 550 street models and 12 R models were built in 1965. That changed significantly in 1966 for two reasons—a redesign to make the cars more unique, and an order from Hertz. The redesign came in part to make the car a street car that was raceable, as well as to give it a look that separated it more from the regular Mustang—there had been complaints that it wasn’t distinctive enough to warrant the additional cost. A number of changes were made. The suspension was softened a little, the exhaust was extended to the rear of the car, quarter panel windows replaced the vents, the Mustang GT gauge cluster was used and the tachometer was moved to the top of the dash, the fiberglass hood was replaced initially with a fiberglass hood with a steel frame and finally with a steel hood, and rear brake cooling scoops were added. And the new G.T.350 could be gotten with several new options—a rear seat, limited-slip differential (now an option), a Paxton supercharger and a variety of new colors. The 1966 G.T.350 now came in white, red, blue or green, with a special black version for the Hertz Sports Car Club. The cars could be had with or without Le Mans stripes—blue on the white cars and white on the rest, except for gold on the Hertz cars. According to the Shelby American Automobile Club (SAAC), there were two prototypes, 1356 street versions, one Paxton prototype and ten production supercharged fastbacks, two Hertz prototypes and 999 production rental cars, four drag cars, four convertibles and one prototype notchback and 20 production notchback racecars. An interesting bit of trivia: the first of the ’66 cars were actually ’65 models. Shelby needed to be working on the new model while the factory shut down for two months to retool for the ’66 Mustang. If Shelby waited, he would not have had the ’66 G.T.350 ready for the new model announcements in September, so he created his initial ’66 models from ’65 Mustang fastbacks.

G.T.350H

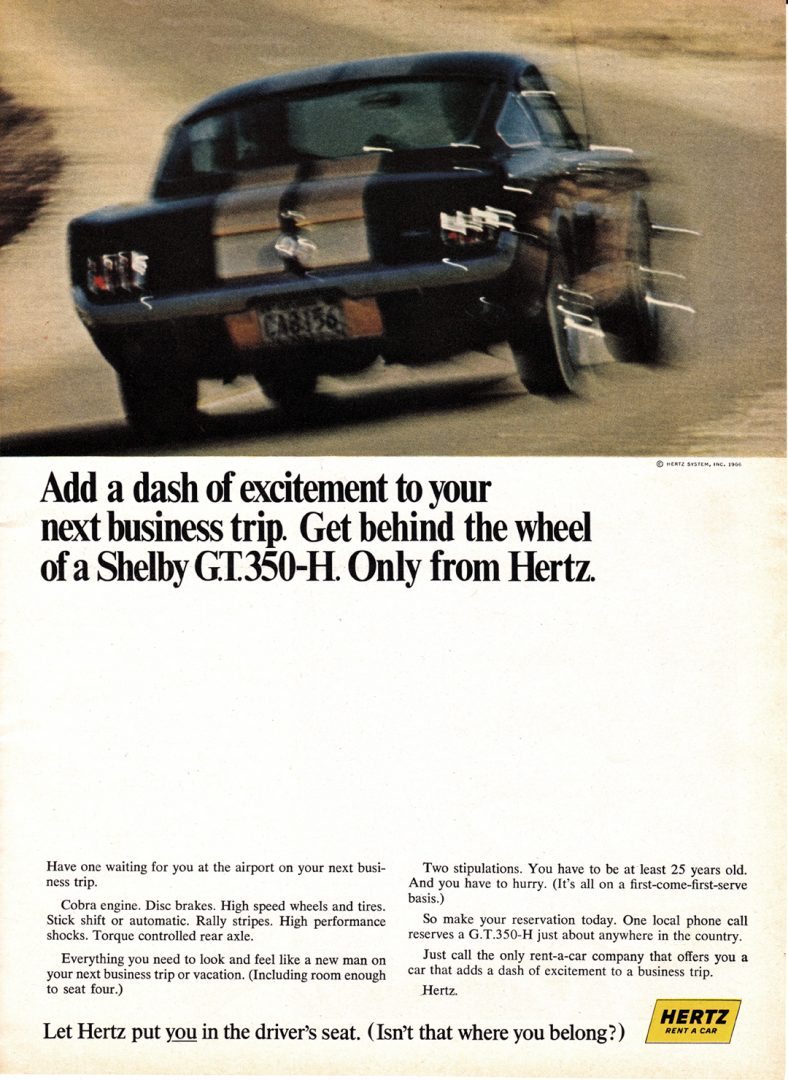

Hertz began renting cars in 1918 and grew to be the giant of car rental firms. In 1958, Hertz created the Hertz Sports Car Club and made more exciting cars available—for a price. Anyone with the money and who could prove he or she could drive a stick could rent a Corvette, Jaguar or Triumph. It was a limited success, since all the Sports Car Club cars were two-seaters. In 1965, Hertz switched its allegiance from GM to Ford and saw an opportunity to expand the Sports Car Club with the 2+2 G.T.350.

Hertz wanted 1000 cars in the company colors—black and gold. Shelby was happy to oblige, since Hertz agreed to pay the normal wholesale, destination charge and a prep fee to the dealer. Shelby provided an additional $50 incentive to the dealers involved with prepping the cars for Hertz. The cars were to be black with gold Le Mans and rocker panel stripes and a 4-speed transmissions. A radio, rear seats and stripes were provided at no charge, although bright wheels added $106 to the cost to Hertz.

There was an extensive ad campaign. Hertz created and placed the ads, and Shelby reimbursed Hertz for the ad costs, with Ford reimbursing Shelby for most of those costs. If it is true that Hertz called the cars “rent-a-racers,” it was an unfortunate choice of words because that could only encourage renters to treat them as racecars.

The shelf life of a rental car was six to nine months, so Hertz wanted the cars in December or January. Deliveries actually began in late December 1965 and weren’t completed until May 1966. That wasn’t the only change to the contract, though. Hertz decided that some of the cars should be automatics and that other colors were needed. By the end of the contract, the biggest majority of the cars, 748, were black and gold, but the rest were white, red, blue, or green. All had gold stripes.

If the contract changes weren’t enough of a distraction, there were the problems the renters had—or caused. The biggest issue was probably the brakes. Homologation required the same suspension on the production and racecars, so all G.T.350s had competition metallic pads and shoes. Renters didn’t seem to understand that the brakes didn’t perform as they expected when they were cold. Then there was the issue of Hertz maintenance, or the lack of it. Renters tended to drive these cars hard. [Well, wouldn’t you?] With poor maintenance, the cars deteriorated quickly. Hertz was required to keep the cars in service for nine months, but warranty claims for brakes were received as late as April 1967, meaning that the average life as a rental was eleven months.

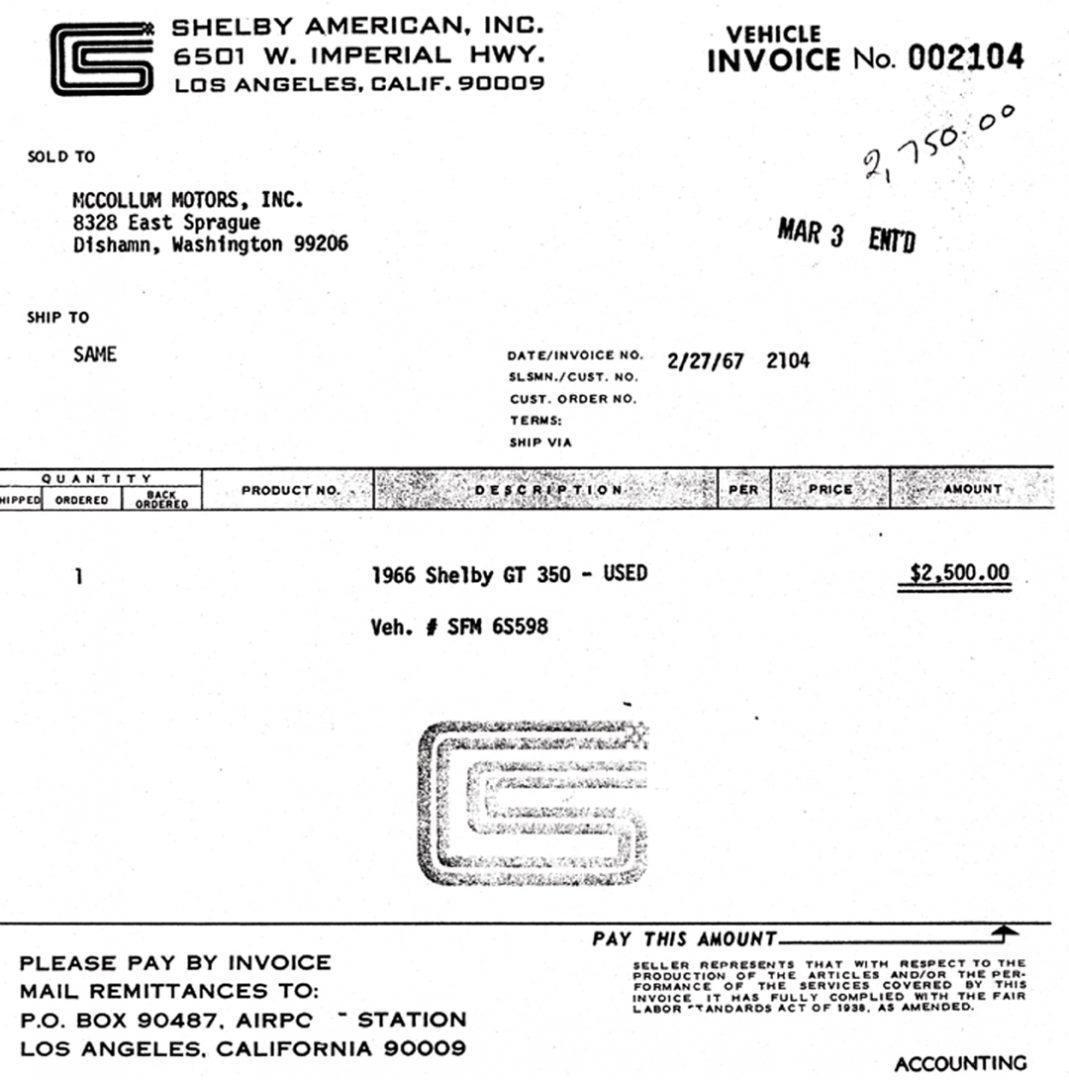

Shelby American agreed to buy the cars back at the end of the contract at a price based on the condition of the car and any reconditioning costs. In order to prevent a mass of cars hitting the used car lots of Shelby dealers when there were new ’66 cars still unsold and the ’67 about to hit the showrooms, it was agreed that 100 to 150 cars would be sold per month throughout the U.S. The cars were either wholesaled to dealers or consigned to auctions to be sold by smaller dealers.

SFM6S598

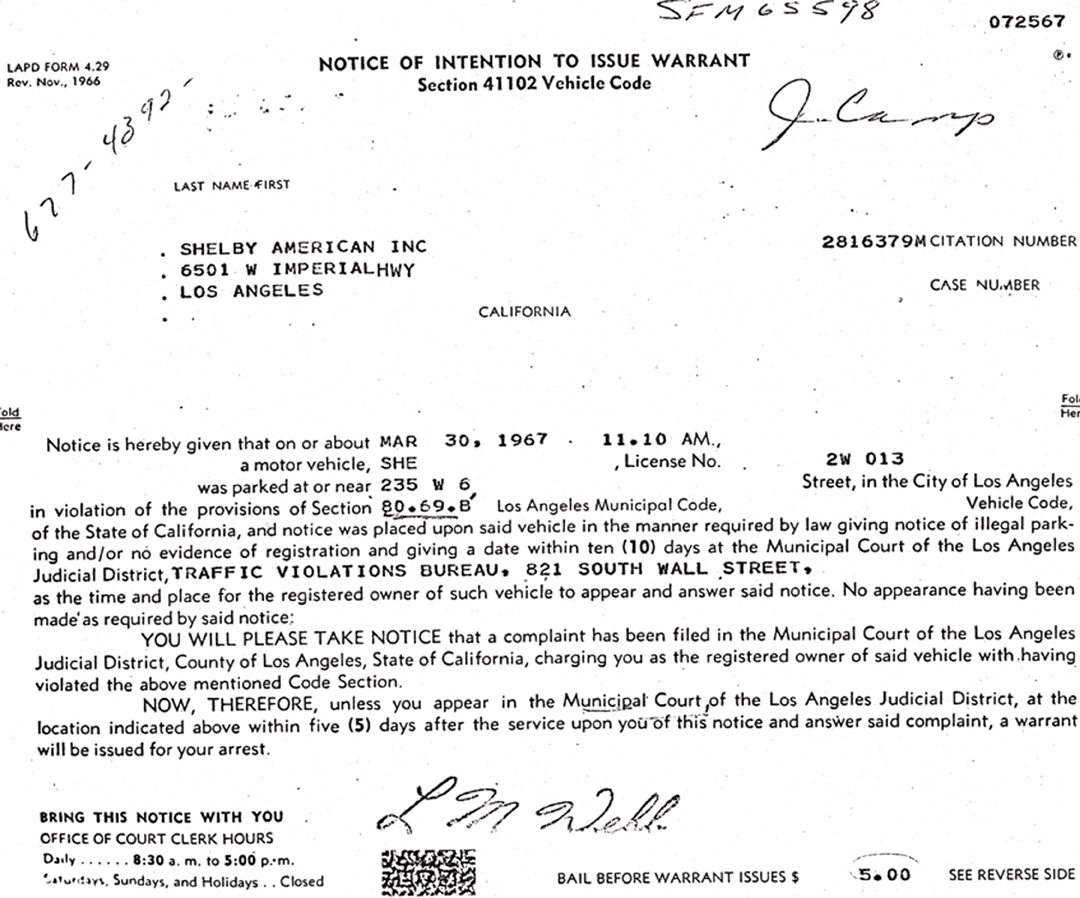

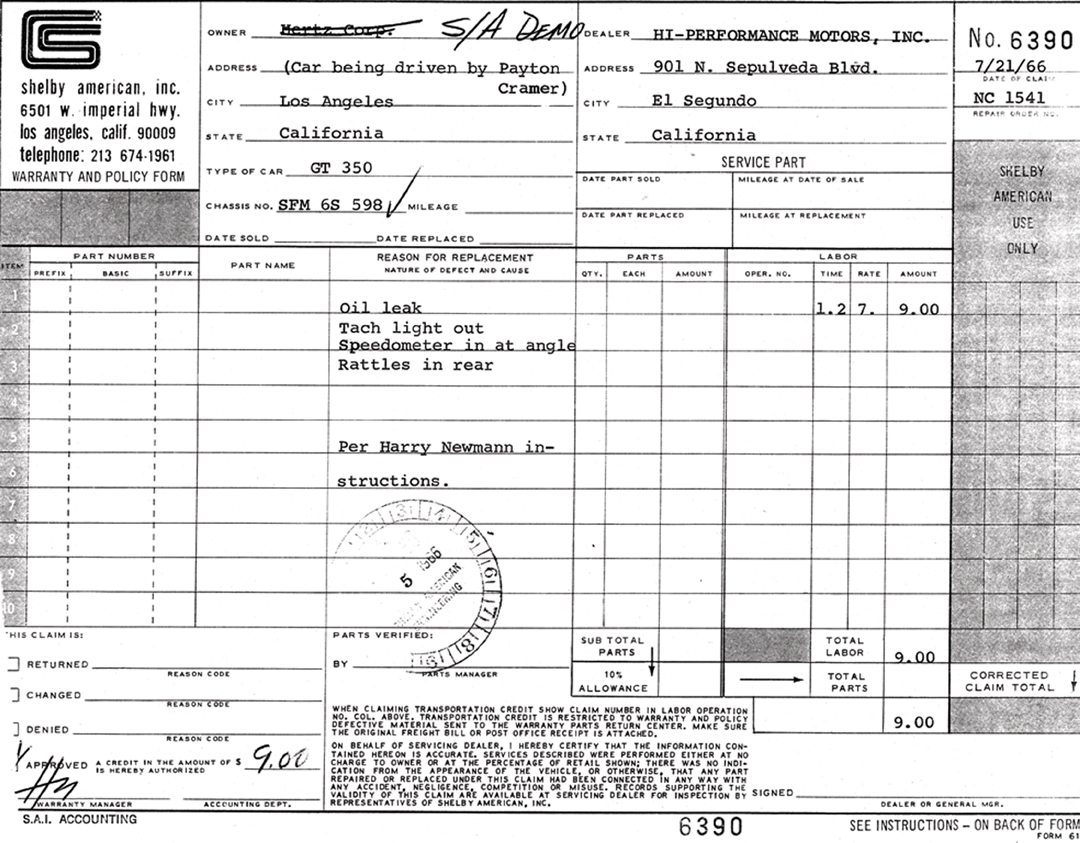

Not all G.T.350H cars were delivered to Hertz. Two, at the end of the contract, were declined by Hertz. SFM6S598 was kept by Shelby, used as a demonstrator and occasionally loaned to important people. It was a relatively early Hertz car—built in January 1966. It was consigned to Ray Geddes, the liaison between Ford and Shelby, and used as a demonstrator by Shelby employees Jim Camp and Peyton Cramer. While this car didn’t suffer the abuse of renters, it was used for a time by Jerry Titus, the SCCA B Production National Champion. Certainly he used the car simply for trips to the grocery store and the movies…right.

There are a few documents that certify the provenance of this car. Whoever was driving the car on March 30, 1967, received a parking ticket in Los Angeles. It was paid by Shelby American in July 1967. There is also a repair ticket for some minor repairs in July 1966 where “Hertz Corp.” is crossed out as the owner and “S/A Demo” is written in. Finally, the car was sold, on February 26, 1967, to McCollum Motors in Dishman, Washington, for $2500. The car was also road tested in the April 1966 issue of Sports Car Graphic and was reprinted in Mustang Monthly in July 2012. Copies of these documents and the magazines are in the possession of the current owner, John Dillman

The car was sold by McCollum Motors, and it had a number of owners while it gained mileage and value from 1967 to the present. Dillman has a variety of interesting cars, but says, “I’d always liked the Shelbys and the color scheme. It occurred to me that the early Shelbys might be the ‘little black dress’ of collector cars. Whether you are in a crowd that likes old cars generally, or road racing cars, or drag racing cars, or sports cars, or muscle cars, or Mustangs, or whatever, they seem to fit right in. Not something you can say about just anything.” He had looked at ‘68s, but he just didn’t like them. He liked the ‘67s, but “I felt the early ones were truer to what I thought a Shelby should be.” So he placed an ad in the SAAC forum, and got an answer from Steve Ainsworth. Ainsworth had some interest in selling, but he wasn’t sure he really wanted to let the car go. He had had a long discussion with another prospective buyer, but they weren’t able to close the gap between what Ainsworth wanted and the buyer was willing to pay. Ainsworth sent Dillman an appraisal of his Shelby together with a photo. The photo also showed a ’57 Chevy convertible. Dillman replied with a photo of his ’57 Nomad that showed much of his garage and his other cars. Ainsworth was impressed. His concern was that the car might wind up with a dealer or a flipper, but Dillman looked like he’d provide a good home for the car, so a deal was concluded. Ainsworth and Dillman have become friends, and Ainsworth has visitation rights to the car, as well as the right of first refusal if Dillman decides to sell it some time in the distant future.

Driving Impressions

This is a very rare Hertz car for two reasons. First, as mentioned earlier, it never went to Hertz but was used by Shelby’s employees and Jerry Titus. Second, it has never been restored. This car has been very well preserved, even through its more than 40,000 miles on the road. The only body work ever done was to repaint a part of the gold stripes that had been burned when they were buffed a bit too energetically. So, I wanted to be careful with this car, but it is a G.T.350, so I needed to see how it compared to my memories of my ’66 (SFM6S2049). Ever since interviewing Dr. Fred Simeone, I keep in mind a criticism he had of road tests of old cars by current writers: “. . . what bothers most now is you get a modern writer, and he’ll either say how wonderful it is because he can get it into gear, or he’ll say how primitive it is because he doesn’t know what cars were like in 1912.” (Vintage Roadcar September 2014) I think about his comment every time I drive a classic car. In this case, I also have my own point of reference.

I had ridden with Dillman the previous day, looking for places for the car-to-car photography. It was just as rush hour was building, and there were quite a few policemen directing traffic. Every one of them noticed the car, with several giving a thumbs up. Dillman made a comment that I tried to remember when I later drove the car, “This car is quick, but not exactly the car to rob a bank with.” It definitely gets a lot of attention.

We drove to a nice Italian restaurant for dinner, and, afterward, Dillman handed me the keys. As I slid into the driver’s seat and buckled the competition lap belt, I had a flashback to when I rallied my Shelby while in the Army in Germany. Oh my, I had already started smiling, and I had not even started the car. This is a comfortable car. The seats are firm enough, there’s plenty of leg room, and even the back seat passenger isn’t cramped—well, not too cramped. I took my Shelby on several long trips and can verify from experience that it’s a nice car for traveling—especially on the Autobahn.

I had already heard the engine—and what a great sound that small block V8 makes—but it was just a bit different when I was controlling it with my foot. Then came the only difference between this car and mine—I slipped the shifter into R, backed out of the parking place, moved it to D, and set off. I actually started for the clutch with my left foot when I first put my hand on the shifter, but I didn’t mention that to Dillman.

We were in the city, so I pulled onto a main road and slowly proceeded to where Dillman suggested I turn right. Ah, open space. . . and I got on it a little. The back end slewed a bit, but not anything disturbing. In fact, I was reminded of how easily one could steer this car with the right foot. We took off through a semi-residential area, making several right and left turns at moderate speed, and I knew this car would be able to do all the things mine did years ago. It cornered flat with a little wiggle that makes the driver smile and the passenger worry. The ride was stiff, steering took a bit of effort, and the brakes, well the brakes need to be pressed hard when they’re cold, as so many renters found out. I shifted it a few times and was pleased with the response of the automatic. Thanks to the shift kit, the automatic is way better than in the Fairlanes for which it was originally built.

The test drive was much too short; of course, any drive short of my taking it home with me would have been too short. The G.T.350 isn’t for everyone, but I suspect it would make most of us car people happy. Of all the cars I have driven for Vintage Roadcar, this has to have been my favorite because it took me back to that first new car I owned.

Sadly, 1966 was the last great hurrah for the G.T.350. Some Ford influence had begun to creep into the ’66, then Ford essentially took over production in 1967 (see “The Only One,” Vintage Roadcar December 2013). Shelby became less and less involved with the Shelby Mustangs until 1969 when the new Shelby GT was totally a Ford design. After assisting with a number of Chrysler products, Shelby was back with Ford in 2003 working on the Ford GT and Shelby Mustangs. Shelby died in Texas on May 10, 2012, at 89.

Racy Tales from the Track

There are many stories about people renting a G.T.350H, taking it to the track, and racing it. I don’t know if any of them are true, but I do know about one G.T.350H engine that appears to have made it onto a race track.

It was in the spring of 1966, and my best friend, Bob Brown, and I went to an SCCA race at Marlboro Raceway in Marlboro, Maryland, a bit east of Washington, D.C. I was a senior in college and was attracted to the G.T.350, so I was pleased to see one racing in B Production. We watched practice and qualifying on Saturday and were disappointed to see the Shelby followed suddenly by a lot of smoke. The hint that it might have been terminal was the length of time it took the workers to clean up the oil on the track. I thought that would be the end of one of my favorite cars in BP.

Bob and I were back at Marlboro in time for the warm-ups on Sunday morning. We were surprised and pleased to see the G.T.350R on the track when we arrived at our favorite corner—the Toe of the Boot. Wow, they must have had a spare engine.

We didn’t know where they might have gotten the new engine until we walked to the grandstands behind start/finish to watch the start of a race. Marlboro was a road course built using part of a banked quarter-mile oval track. Start/Finish was on the tiny straight in front of the grandstands, and the paddock was in the infield of the oval. When we looked into the paddock from the grandstands, we saw a black and gold G.T.350H sitting near where we had seen the G.T.350R the day before. The white and blue car was nearby, but what caught our attention was the stance of the Hertz rental car—its front end was sitting unusually high, as though a significant weight had been removed from its engine compartment. I’m not saying it was the engine from the rental car, but ….

GT350H Specifications

Chassis: Unibody, welded

Body: Steel and fiberglass

Engine: Cast iron, pushrod V8 with cast iron head

Displacement: 289cid/4735cc

Bore/Stroke: 4.05/2.87 inches; 10.29/7.29cm

Power: 306bhp @ 6000rpm

Torque: 329lbs-ft @ 4200rpm

Compression Ratio: 10.5:1

Induction: 600cfm Holley 4-barrel

Exhaust: Dual exhaust with glasspack mufflers

Transmission: Ford C-4 three-speed automatic with special servo assembly and “shift kit”

Clutch: Single dry disk

Front Suspension: Unequal arms, coil springs, adjustable tube shocks, anti-roll bar

Rear Suspension: Live axle, multi-leaf springs, adjustable tube shocks

Wheelbases: 108 inches/274.3 centimeters

Front Track: 56 inches/142.2 centimeters

Rear Track: 56 inches/142.2 centimeters

Length: 181.6 inches/461.3 centimeters

Height: 51.2 inches/130.1 centimeters

Width: 68.2 inches/173.2 centimeters

Weight: 2,940 pounds/1333.6 kilograms

Brakes: Front – 9.5-inch Kelsey-Hayes discs; Rear – 10×2.5-inch drums

Steering: Recirculating ball