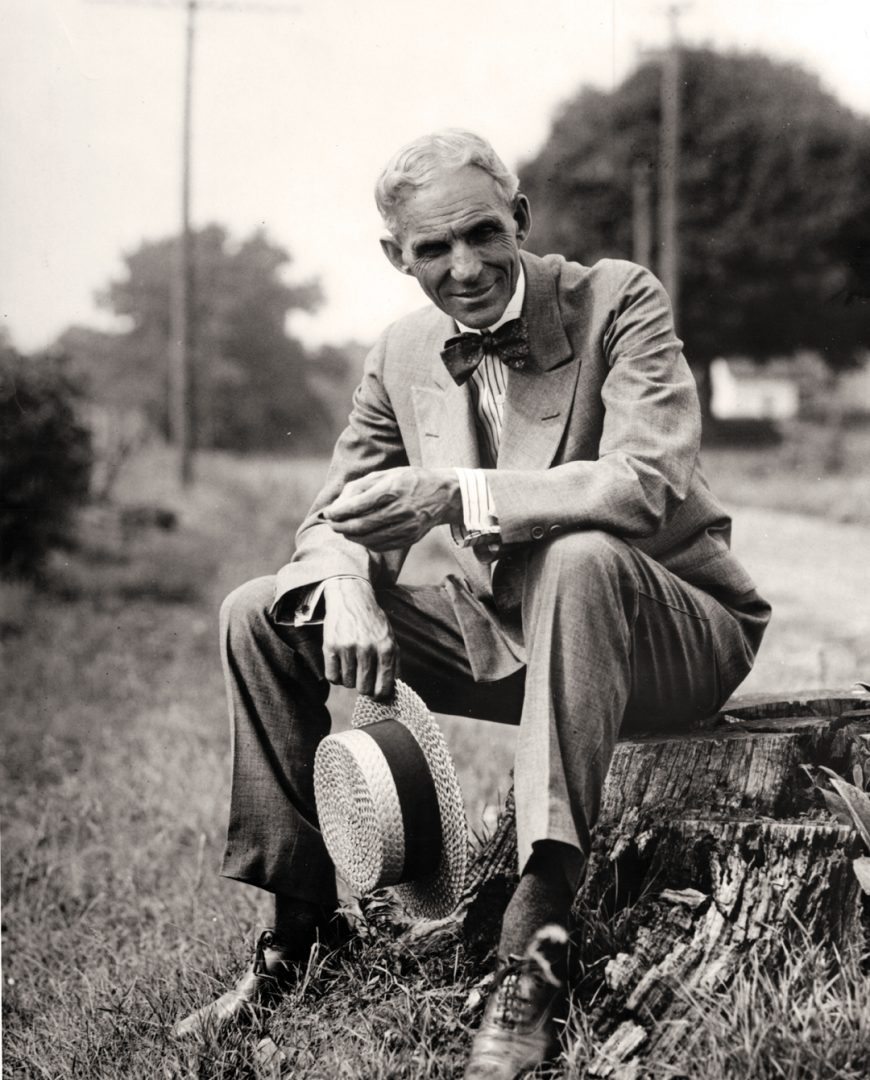

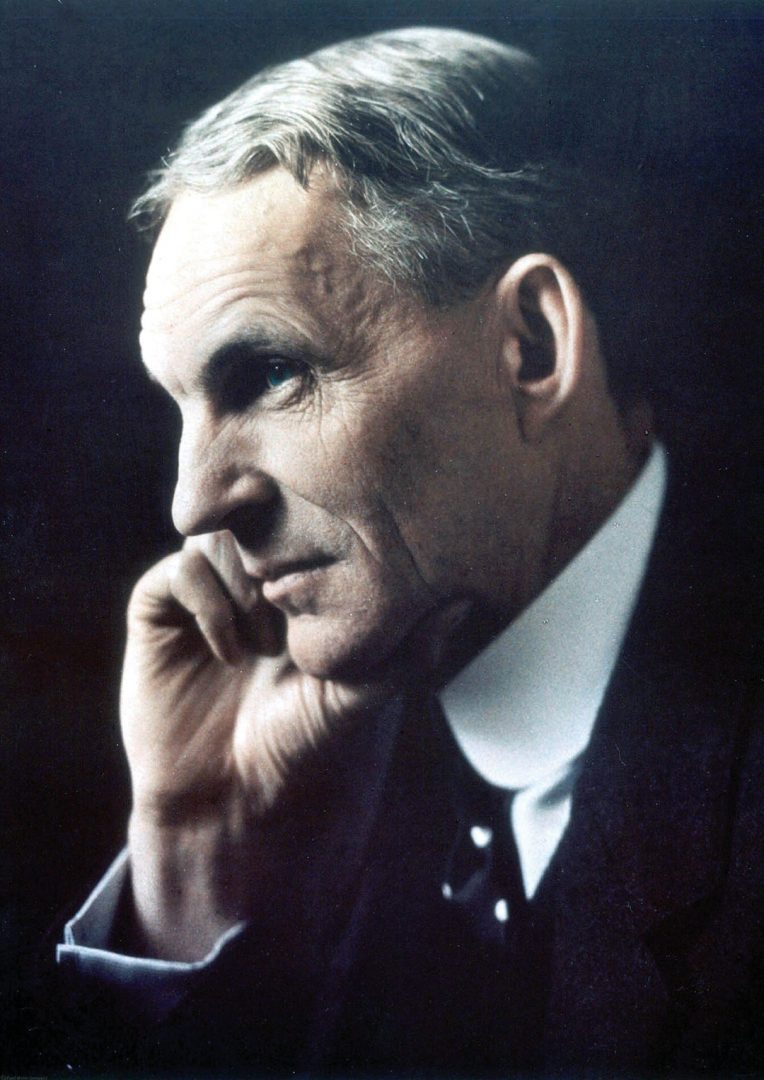

Henry Ford was truly one of a kind: egotistical yet compassionate; rich yet thrifty; genius yet ignorant. No man— industrialist, philanthropist or entertainer—before or since, has garnered as much fame and notoriety as Henry. Yet, he was a man like every other. A close Ford acquaintance wrote, “So much has been written about Ford—how great he was, and how he put America on wheels—that the public has lost sight of the eccentric flesh-and-blood man behind the cardboard poster.”

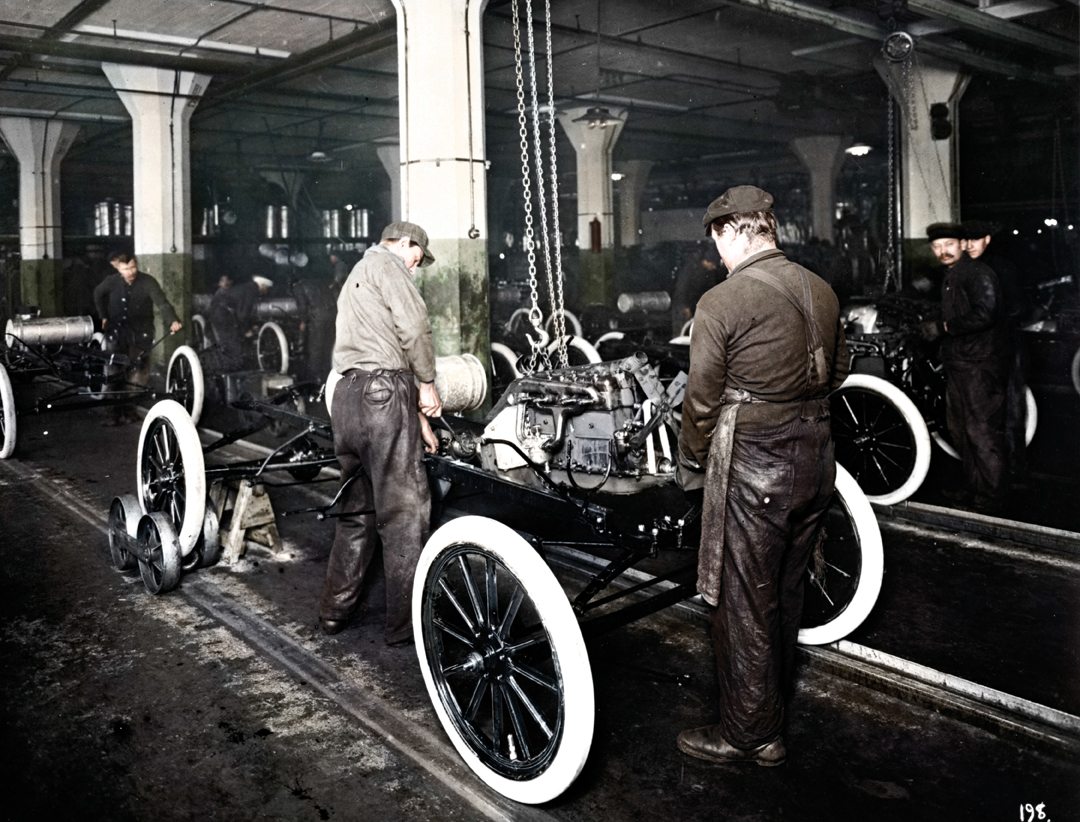

The rise of Henry Ford began on June 16, 1903, when he and eleven other men staked their hopes, aspirations, and savings on the creation of the Ford Motor Company. Those who stayed with Ford for 16 years walked away multimillionaires, but Henry was the driving force in the company. He had a vision of building lightweight, well-made, inexpensive automobiles that the average man could afford; he sold them by the millions, and it made him a fortune.

Henry ruled the company with an iron fist, and anybody who didn’t agree with him was either fired or bought out. “There was only one boss,” recalled a longtime Ford employee, “and he was The Boss.” In 1919, flush with money, he bought out the other stockholders, at a cost of $105,000,000, and ended up owning the company outright. People in the company didn’t call it “Ford Motor Company,” recalled another longtime Ford employee, “they called it Mr. Ford Motor Company.” For another quarter of a century, Henry Ford did what he pleased, when he pleased, and how he pleased.

Eventually, the end came, as it does for everyone. But in a way, Henry had died several years before. The first blow occurred when his son, Edsel, died in 1943. And the penultimate blow came when he suffered a severe stroke in 1945, which affected his cognitive powers.

Author Henry Dominguez wrote: “My book The Last Days of Henry Ford started out to be the story of Henry Ford’s last day. But I decided to expand it to cover the year before his death, the viewing and the funeral after his death, and the death of his widow, Clara, three years later. The week surrounding his death would have made an interesting story, but I wanted to give the reader a sense of who Henry Ford was, what he had become during the end of his life, and how his wife carried on after he was gone. Some of this material has been written about before in articles or a few pages of a book, but never in such detail.

“In my 40 years of studying Ford history, I have known that there is plenty of material available pertaining to Henry Ford’s last day. Interviews of Ford employees conducted in the 1950s provide some of that material, particularly the Reminiscences of Robert Rankin, Henry and Clara’s driver, who spent most of that last day with Ford. But it was the interviews of Floyd Apple, a worker at the powerhouse at Fair Lane (the Ford estate), and of Rosa Buhler, the Fords’ maid, that provided the almost hour-by-hour account of Henry Ford’s last hours. Both of those series of interviews were conducted by Ford aficionado Richard Folsom, in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Buhler lived in the mansion with the Fords, and was in the Fords’ bedroom with Clara when Henry died. She told Folsom the sad story in great detail.

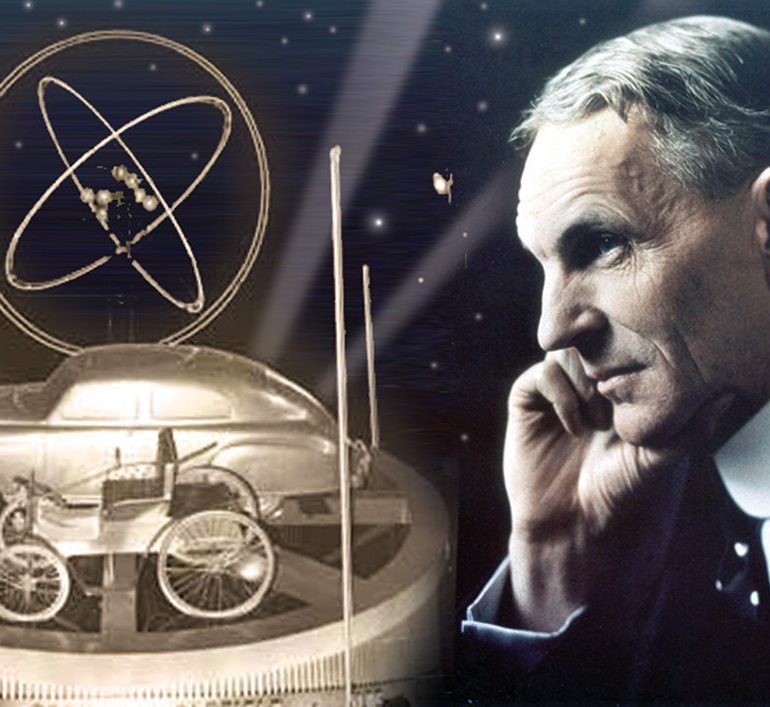

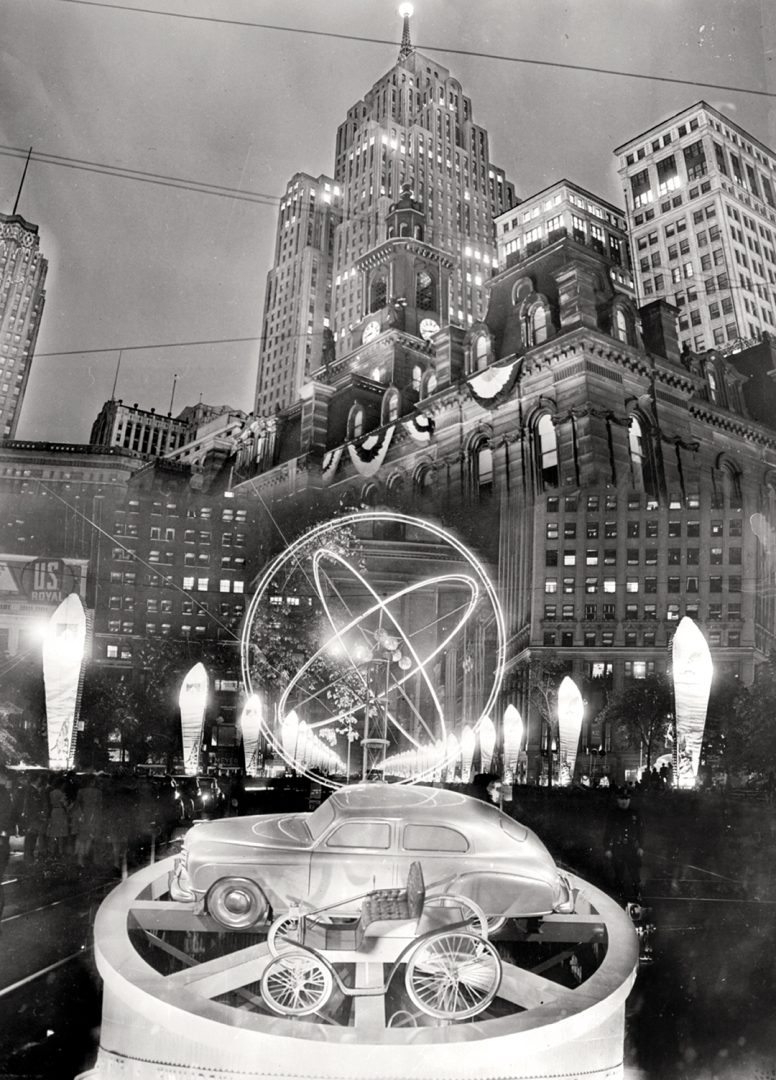

“One of the more important events that Henry Ford attended in the year before his death was The Automotive Golden Jubilee, in May 1946—a weeklong event that the city of Detroit put on to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Charles Brady King and Henry Ford taking their first cars out on their maiden voyages. Not much has been written about that extravaganza, but the National Automotive History Collection (NAHC) at the Detroit Public Library has a vast set of newspaper accounts, publications, and photographs pertaining to the Jubilee. Interestingly, in the accounts of the 1946 Jubilee, these records were made for posterity and were intended to be listened to 50 years later, for the automobile’s 100th anniversary, in 1996. But they had been forgotten, and were not listened to for 65 years, until April 2012.

“The information that these records held in their valleys and grooves turned out to be precious to my research. In crystal clear quality, a reporter can be heard giving a minute-by-minute account of the awards ceremony at the Jubilee. If all of my work on this book had come to naught, just listening to that recording would have made all my effort worthwhile. Fortunately, it didn’t turn out that way, and I was able to describe Henry Ford’s last major public appearance in my chapter on the Jubilee.”

During a Detroit city council meeting in March 1946, the idea was brought up to celebrate the city’s sesquicentennial along with the one-year anniversary of the end of World War II and the 50th anniversary of the automobile in Detroit. While the city’s birthday and the end of the war were included, the celebration ended up concentrating on the automobile, since the motorcar industry had become such a powerhouse for the region.

The city council appointed former Detroit Mayor Edward Jeffries as Honorary Chairman of the Jubilee Committee and they allocated $1 million to stage the event, which they called The Automotive Golden Jubilee.

On the evening of Friday, May 31, an event occurred that would never be duplicated again. For the first and last time, 14 pioneers of the automobile industry were brought together so that their contributions could be recognized and celebrated. Fortunately, the event was held then, and not one or two years later, for by then most of these men were gone. Already, a number of famous pioneers had died. Henry Leland, founder of both Cadillac and Lincoln, had died in 1932, at the age of 89. Walter Chrysler had died in 1941, at the age of 63. Benjamin Briscoe, president of the Briscoe-Maxwell Motor Company, had died in 1945, at the age of 78. James Couzens, one of the original 12 stockholders of the Ford Motor Company, had died over a decade before.

A few automotive pioneers were, however, still around, and they were all brought to the majestic Masonic Temple that evening to celebrate their accomplishments and to be inducted into the newly created Automotive Hall of Fame: Edgar Apperson, Frank Duryea, George Holley, Charles Brady King, Frank Kwilinski (factory worker), Charles Nash, Barney Oldfield, Ransom Olds, Charles Snyder (an early dealer), John Van Benschoten (another early dealer), John Zaugg (another factory worker) and, of course, Henry Ford. General Motors founder William Durant and then-chairman Alfred P. Sloan were also to be recognized, but regrettably both were ill and could not attend. One-by-one they were dying off, these men who had created a great industry and put America on wheels. Henry must have felt fortunate to have outlasted most of them.

All of the pioneers were assigned an escort to guide them through the activities of the day. Henry’s escort was his own grandson, Henry II. Dinner was to start at 6:30 p.m. in the Fountain Room of the Masonic Temple. Before that, however, all of the pioneers were taken to a smaller room next door to sign special white cards, from which their signatures would be emblazoned on a bronze plaque for posterity. One by one, the pioneers entered the room, anxious to sign their card so they could spend more time reminiscing with their fellow pioneers. The room was full of chatter when everyone suddenly noticed that one of them was missing. Where was Henry Ford?

Then they heard the door open, and there was Henry, on the arm of his grandson, slowly walking in. Everyone stopped talking, as if there had been a call to order, and there was an awkward silence.

It took King only a matter of seconds to recognize the situation. He raced across the room with his hand out, saying, “Hi, ya, Hank!” Everybody was dumbfounded—and Henry II was a little perturbed—for no one ever called Henry Ford “Henry,” let alone “Hank.” But King had known Henry before he had become rich and famous, and he had called him Hank back then, so he saw no reason to change. Henry smiled and shook King’s hand. “Hello, Charlie.”

The pioneers were just catching up when they were asked to make their way to the Fountain Room for the tribute dinner. The room was jammed to capacity with automotive executives, government officials, and close friends.

“I went on into the dinner with Henry Ford on one side of me and Charles King on the other,” recalled Holley. “Mr. Ford didn’t seem to have the memory that he had ten years before that period, but he recognized different people that evening. He still had a humorous side.”

The pioneers were directed to a long table and sat in alphabetical order. Henry sat between Frank Duryea and George Holley. While he had never met Duryea before (although he certainly knew of him), he and Holley were friends from way back.

Henry passed on dinner, ordering only two glasses of milk. And when the waitress asked Holley what he wanted to drink, he ordered milk as well. “Here we are,” Ford told Holley, “two old buddies growing old, and drinking milk together.” Holley laughed.

Then the finale began. The conductor struck up the orchestra, lights flooded the stage, and the curtain rose. The audience’s applause was thunderous as the 14 pioneers came into the spotlight. They were seated in alphabetical order on a dais, on either side of which were the present executives of the various automobile and truck manufacturers. For the next two hours, the pioneers were paid homage before an admiring audience.

The MC for the evening was the Automobile Manufacturers Association president (and future American Motors president) George Romney who said: “After each individual citation is read…, and I’m going to ask each of the pioneers to stand as his name is called, and stand while the citation is being read, and remain standing until our beloved friend and great benefactor, General William S. Knudsen, presents them with their individual award….”

Then it was Henry’s turn. He was the pioneer that the entire audience had been waiting to see. Romney stepped up to the microphone: “Mr. Henry Ford! Will you stand up, Mr. Ford?” As Henry slowly stood up, recalled Robert Rankin, he was “greeted by a thunderous ovation as the capacity audience rose to their feet. I looked up to see if the roof was going to go off!”

When Knudsen walked over to the dais and handed the master of mass production the award. In his typical fashion, Henry did not say a word—not even “Thank you.”

As the ovation continued, Romney pleaded with the audience to let him go on. Finally, everyone settled down and allowed the show to continue. But the rest of the presentations were anticlimactic compared to Ford’s. The committee should have seated the pioneers so that Ford was last. As it was, the remaining 11 pioneers were upstaged by Henry Ford once again.

After his own presentation was over, Henry quickly lost interest. He “kept looking at his watch,” said Rankin, wondering how much longer this was going to take. He didn’t mean to be disrespectful; it was just that “he was a restless man. He wanted to be going all the time.”

The highlight of the evening, at least for the pioneers, was the reception after the awards ceremony, when they would get to spend some time with each other. Except for Apperson, Duryea and Nash, Henry was well-acquainted with the other pioneers. He was alert again after the awards ceremony, and he was delighted to talk with his old friends, Oldfield, Holley, King and Olds.

The last time he had seen Barney Oldfield was at the 1932 Indianapolis 500 race. Oldfield had had a cigar in his mouth then, and he had a cigar in his mouth now. Henry walked up to him and shook his hand.

“Well, Barney,” he said, “I made you, and you made me.”

“No, Henry,” Barney replied, ashes dropping off his cigar, “old 999 made us both.”

Tall, lithe and nattily dressed, Charles Brady King was a healthy 77-year old. He was seated on the other side of George Holley, and all through the awards presentation he could be seen leaning across Holley, talking to his old friend, Henry. Obviously, there was so much the two could have reminisced about that evening, and they would not have much time after the ceremony, with Henry talking to the other pioneers. Unlike Henry’s other friends on the dais that night, King had kept in touch with him over the years. Whenever he saw Henry’s name in the newspaper, announcing another one of his accomplishments, King would write him a congratulatory letter.

After building his first motorcar, King went into business building marine engines. After several years, he sold the business to Ransom Olds, who hired him to oversee production. In 1902, King joined the Northern Manufacturing Company—makers of the Northern automobile—as its chief engineer. He held that position for six years, and then spent two years in Europe, studying art and automotive design. When he returned to Detroit in 1911, he founded the King Motor Car Company, and produced his namesake motor car for five years. He did quite well in the automobile business, and in 1924 bought a large estate in upstate New York, living a life of leisure.

In 1929, King had read about the magnificent museum and village that Henry had built, and made plans for a trip to Dearborn to partake in their grand opening festivities that October. While he was in town, he planned to see the old Bagley Avenue house where he had been the witness to automotive history.

Before building the Quadricycle, Henry had built a rudimentary gasoline engine so that he could prove the operation that he had only read about in magazines. He made it out of a piece of metal pipe and other scraps of metal, and mounted everything to a board. When it was ready on Christmas Eve 1893, he asked King to come over to help him start it for the first time.

Clara was displeased. It was Christmas Eve and it was late. Couldn’t Henry wait at least until tomorrow to test it?

Henry could not wait. He and King carried the rudimentary engine into the kitchen, clamped it to the sink, and got electricity for the “ignitor” from the light receptacle hanging above the sink. Then Henry spun the flywheel while King carefully poured gasoline into the engine. It would pop, spit fire out the intake, and blow smoke throughout the house. Henry had thought that it would start up right away, but it took them well into Christmas morning before they were able to get the little engine running with any consistency.

Clara finally gave up. Edsel was too wide awake and excited now to get him to sleep, so she took him upstairs and they played together.

An hour later, Henry and King finally got the engine to run smoothly, and Henry was elated. Now he could turn to building a horseless carriage.

“This was his first gasoline engine,” King recalled, and that’s why King wanted to find the house again.

When he wrote Henry of his plans to visit the house, Henry wrote back, “There is no picture or record of this house. It was torn down and destroyed and nothing left. The Michigan Theater is on the site. I have a small photo of the small shop in rear, and that is all. The house had a second story. I remember that.”

King asked Henry for a copy of the photograph of the shop.

“C’mon out and get what we have,” Henry replied.

When King arrived at what had once been 58 Bagley Avenue, it appeared that Henry was correct: the old homestead had been torn down. But then King went around to the back of the theater and was surprised to see the old house standing there! The historic building had not been torn down after all, but simply moved from Bagley Avenue to Grand River Avenue. The front parlor of the old house had been turned into a “modern store front,” recalled King, but the back of the house remained as it had been when the Fords lived there.

When King realized this, memories began flooding through his mind. “Before me was that kitchen where we tested the first little engine into the small hours of the morning,” he recalled. King well understood the significance of what had taken place there: “What

if Wreford was unable to collect the rent, and what if Strelinger’s tool bill had not been paid?” But Henry did pay his bills, and was able to complete his Quadricycle, “and with it came riches such as no one man ever knew before,” recalled King.

For the next few days, King made detailed architectural drawings of the old Ford home, and took them to show Henry.

“I have found Bagley Avenue!” King exclaimed. “I can’t believe it!” Henry said.

In time, Henry bought the brick from the old home, replacing it with new brick, and used the original brick to recreate the little coal shed workshop on the grounds of Greenfield Village.

“There was luck in every brick of old 58 Bagley!” exclaimed King.

“Yes!” replied Henry.

That was the last time King had seen Henry until the night of the Jubilee. King never begrudged Henry’s success. “I knew him as an engineer in the Edison power plant,” he recalled, “and I know him as one who later associated with the highest authorities, here and abroad. To me, he is the same Henry Ford of simple taste, direct action and forceful thinking.”

Of all the pioneers present that evening, Henry probably admired Ransom Olds the most. If it hadn’t been for some unfortunate business decisions that Olds had made early on, and just plain bad luck, his name could have been the four-letter word that became synonymous with the low-priced car for the masses. Henry and Olds were not close friends, but they had kept in touch over the years.

Tonight, the bespectacled Olds, short and stocky, with thin white hair and white mustache, looked good for a man of 82 years. He was sporting that perpetual smile for which he was famous, thrilled to be honored for his accomplishments and near-accomplishments.

While Henry was diligently building the Quadricycle, Olds was already in business, building gasoline engines—not for automobiles, but for marine use. Two months after Henry had taken his Quadricycle for its first ride, Olds had driven his first gasoline-powered motorcar; and just a few months later, the Olds Motor Vehicle Company was founded.

By the end of 1897—almost two years before Henry had started his first business—Olds had sold ten vehicles. “I have made a careful study of the business for a great many years,” he said, “and predict that the automobile business will be one of the greatest industries that the country has ever seen.”

By early 1900, the company, now called the Olds Motor Works, had a new plant, probably the first building in the United States constructed specifically for the manufacture of motorcars, on the outskirts of Detroit on Jefferson Avenue. “The Largest Automobile Factory in the World” read the sign atop the building, in which a hundred men were employed.

The Olds plant was only about three miles from the Fords’ home, so Henry often rode his bicycle by there, dreaming of the day when he, too, would have such a grand facility. Charles King, who was now working for Olds, kept Henry informed of the goings on in the plant, gave him tours of the facility, and eventually introduced him to Olds.

“At the time,” recalled Olds, “Mr. Ford was an engineer at the Edison plant. He had his afternoons free and was therefore much interested in my production of the little Olds Curved Dash. I advised him that I thought it was going to be a great business, and he ought to get into it. At that time, he said nothing about having ever made a car.”

The first time Olds became aware of how involved Henry was in building automobiles was in October 1901, when he read about the upcoming competition between Ford and Winton at the Grosse Pointe Township racetrack. Olds closed his automobile factory on the Detroit River for the day, so that he and his men could watch the well-publicized race.

By 1903, when the Ford Motor Company was founded, Olds was already on the verge of applying mass production techniques to automobile manufacturing, and had, in fact, already produced nearly 10,000 machines! “Why there is no limit to them,” Olds said. But just as he was making these monumental steps, his factory burned down. He rebuilt it, not in Detroit, but in Lansing, as a sign of a new beginning. But the new factory and the new location did not change Olds’ luck. He soon ran into financial difficulty, and lost control of the company in 1905. The new managers could not pull the company out of its dire financial straits, and sold it to Billy Durant for a song in 1908. Perhaps to erase any demons, Durant changed the company’s name again, this time to Oldsmobile.

While Olds was suffering these dilemmas, Henry’s business was thriving, and in the same year that Durant brought Oldsmobile into his fold, Henry introduced the Model T.

Now, in 1946, Henry made his way through the crowd and grabbed Olds’ hand, congratulating him on his award. The last time they had seen each other was in 1939, when Henry and Clara attended the 50th wedding anniversary of Olds and his wife, Metta. Unfortunately, Henry and Olds didn’t have time to recount all of these historic events on the night of the Jubilee. They were just glad to see each other once again, in the twilight of their lives.

By now it was getting late, and the stories had been told and retold. Fortunately, photographers were there to record the momentous event. In one of those photographs stand Henry, Olds and King—three of the earliest makers of automobiles. Ten months later, Ford would be dead.

Rankin took Henry’s arm and escorted him out of the auditorium, with Clara walking right behind them. They were halfway out to the car when Rankin realized that Henry had left his award on the dais, and had to go back to get it for the old man.

As they were driving back to Fair Lane, Henry and Rankin made small talk, recounting the evening’s events. “Why’d you keep looking at your watch?” Rankin asked.

“They talk too long!” Henry replied.

Nearly a year later, as the pallbearers carried Henry’s coffin down the steps to the waiting hearse, its rear door already open, a lone policeman saluted. Just as the pallbearers lifted Ford’s coffin into the hearse, the car started to roll away! A quick-witted newsman, almost dropping his camera, flung open the driver’s door and pulled up on the parking brake. As Rufus Wilson once said about his old boss, “He was always in a hurry to get someplace.” And it appeared that his last ride was going to be no different.

Excerpted by Sarah Morgan-Wu from “The Last Days of Henry Ford” published by Racemaker Press, www.racemaker.com.

“Uncle Henry”

Henry was very generous with his grandchildren, nieces and nephews throughout the year, not just at Christmas. “Uncle Henry,” recalled Grace, “gave me my first bicycle and my first car, and he taught me how to drive.” He began the lesson by taking her out to a sandy road and having her get stuck so that he could show her how to get unstuck. “Keep it straight,” he told her. “Don’t race the motor.”

Teaching her how to drive on the streets was another matter, because the man who put the nation on wheels did not drive very well, as we know from close family members. “He was absolutely the worst driver who was ever born,” recalled niece Frances ImOberstag. And Grace noted that “he’d bump a curb, or go over a curb.”

It wasn’t that Henry couldn’t drive, he just couldn’t stay focused long enough to drive safely. “He was so busy looking at other things,” Grace said. Carol Lemons agreed. “I went for a ride with Uncle Henry one sunny

afternoon,” she fondly recalled, “and boy was that scary! My uncle was a terrible driver because he was always experimenting while he was driving. All the time, he was figuring out things. We had to cross Telegraph Road, one of the busiest roads around, and my God, I thought we wouldn’t make it! Oh, it was really scary! But we made it. We didn’t wreck!”

To make matters worse, Henry “used to really drive fast,” recalled his cousin, Arthur Litogot. One time, Henry was riding along with Arthur’s father in his new Model A, and they were “going wide open.”