1967 BRM H-16

Photo: Peter Collins

The history of Grand Prix racing is dotted with great and successful winning designs, and is equally littered with no-hopers—the Life Grand Prix, the Bellasi, Merzario, Coloni, Derrington-Francis—and then there were all those with potential which never quite made it: ATS, Beatrice, DeTomaso, Fittipaldi and many, many more. Some of the small outfits made some superb cars…Eagle and the Weslake V-12…and some big teams made some real losers…Ferrari and the 312B2 and Lotus and the Type 80.

BRM probably had as checkered a history as any racing team ever, creating immensely complex and totally unmanageable cars, then winning the World Championship and finally going back to producing some awful machines before closing down. BRM had moments of glory and moments of despair…in about equal measure. Just when the future looked rosy, something would come along to bring back the doldrums. The H-16 project was one of those somethings. Amazingly, when it all looked hopeless, the proverbial phoenix would again rise from the ashes, as did the V-12 Grand Prix winners of 1970–71. However, the H-16 was never going to be a phoenix, and with all that weight, could hardly rise from the paddock never mind the ashes. Yet, it somehow attained a sort of iconic status…the glorious failures that so many racing people love to hate, and then miss greatly when they are gone.

BRM in the Mid-1960s

Photo: Peter Collins

When Formula One adapted 1.5-liter rules for 1961, BRM was one of the teams caught with their heads in the sand, resulting in the two-year-old P48 having to do for many races with a Coventry-Climax engine. Then came the next version of the space frame chassis, a 48/57 with this Climax engine until Tony Rudd was given an ultimatum for 1962…make the P57 work or the team is finished. Rudd took this space frame and made a winner of it with a 1482-cc V-8 designed by Peter Berthon and refined by Aubrey Woods. The car won the Constructors’ Championship and Graham Hill the driver’s title, narrowly edging out Jim Clark and Lotus. The 1963 monocoque P61 wasn’t as good with the chassis tending to flex, but it still performed well enough to finish 2nd to Lotus. The P261 was essentially a P61 Mk.2 for 1964/65, and in true BRM style, 1964 also saw an attempt to build a four-wheel drive F1 car, the P67, which Richard Attwood was to race in the British Grand Prix. It didn’t work and wasn’t raced. Attwood admitted that, although he drove various BRMs, he often didn’t know what their designation was. Attwood says the BRMs were often known as the “V-8s” or the “H-16s.” BRM had several cars which tended to be referred to by their engine type…the H-16…rather than their chassis type, unlike the Lotus, which was the Type 25 or 33 or 49, using the chassis designation. As with many things BRM, this would cause some degree of confusion for historians later on.

Enter Complexity

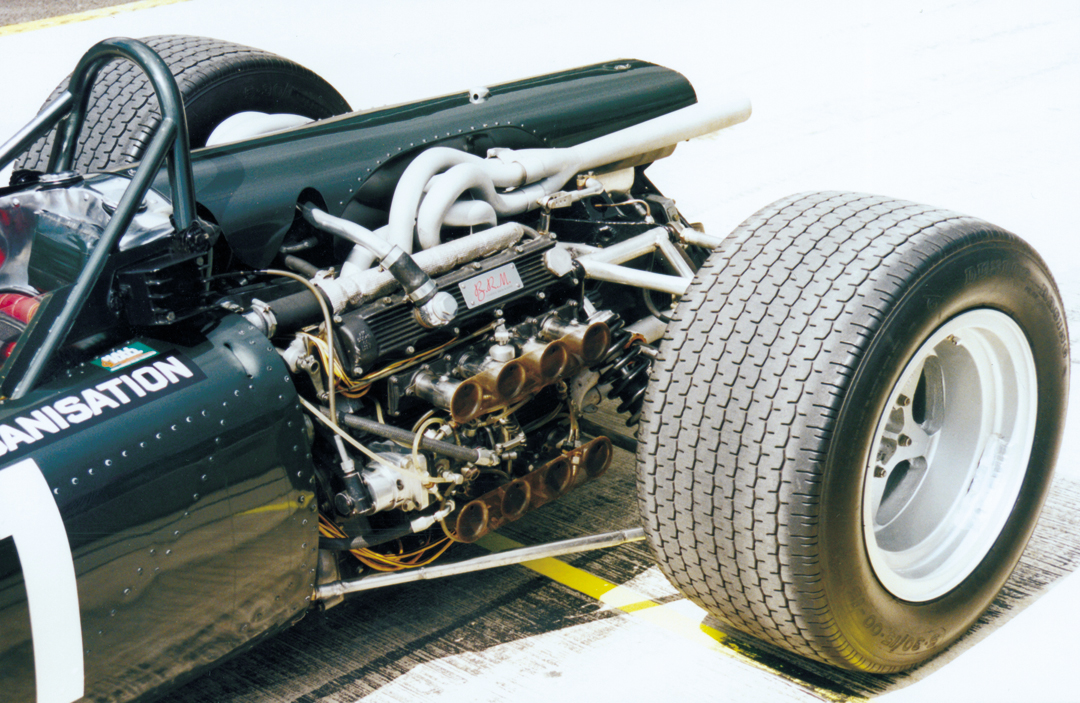

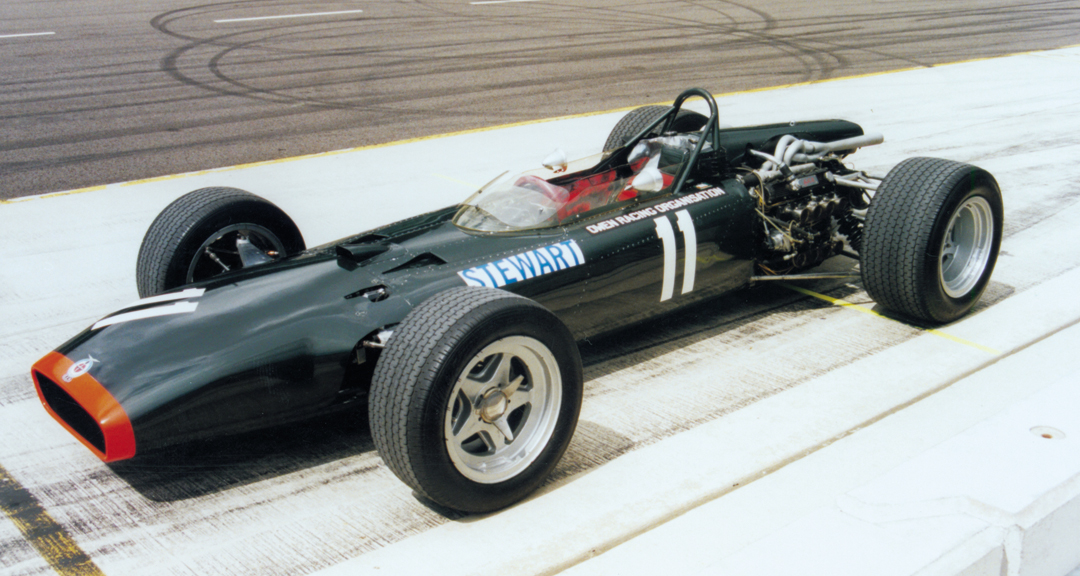

The P61 had been reasonably successful, and like the P48, carried on into the era of the 3-liter engine regulations, which started in 1966, though it used a 2-liter motor (or rather three variations of the bored-out 2-liter.) In fact, private teams used the P61 until 1969. However, at BRM headquarters in Bourne, the new rules saw a return to the old school of over-complex thinking. The new chassis for 1966 was known as the P83, but the car was virtually always referred to by the heavy old lump at the back…the H-16. In fact, that label was so effective, relatively few people knew there was a new chassis in 1967 which is, in fact, the car you see here. The car was simply referred to as the H-16 because the engine was the aspect of the car which dominated its performance, or rather lack of it. Indeed, there was even a third chassis type which hardly anyone knows about, but we will come back to that. Let’s stay with 1966 for the moment.

Photo: Peter Collins

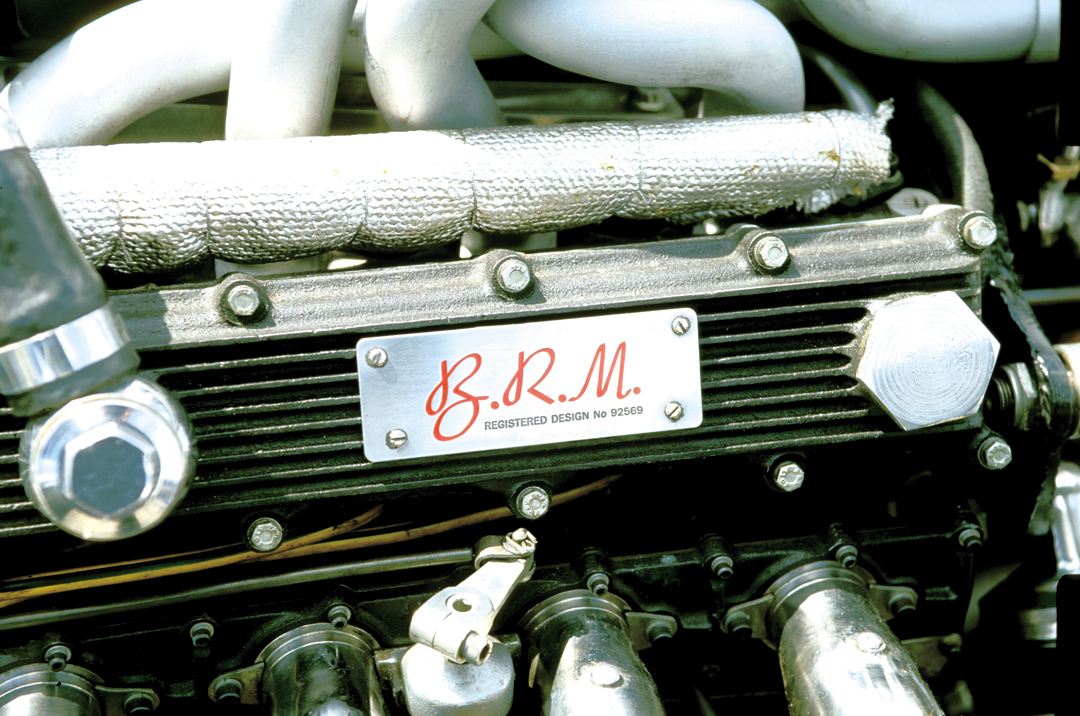

The BRM 1.5-liter V-8 which had been used in the 1.5-liter years of 1961–65 was the type P56 engine, and for 1966 Chief Engineer Tony Rudd took a pair of these engines with the cylinder banks laid horizontally and mounted them one above the other with the crankshafts geared together. The P83 forward monocoque is often thought of as having pre-dated the Lotus-Cosworth with the engine and gearbox bolted rigidly onto the chassis’ rear bulkhead. However, this had already been done the previous year with the Ferrari 1512. The BRM H-16 engine was quite heavy though it tended to look more compact behind the rather squared-off chassis.

Tony Rudd openly admitted to having “mixed feelings” about the H-16 from the beginning of the project, feeling that in some ways it was Alfred Owen’s desire to make up for the disaster of the V-16 in the early days that pushed the development along. It was Rudd’s view that BRM had achieved a near ideal target with the design of the two valves per cylinder, 1.5-liter V-8 engine with the center exhaust. He saw the 187.5-cc per cylinder as the best formula for a Grand Prix engine, and when the 3-liter regulations were on the cards, this meant 16-cylinders and two flat-eights lying on top of each other. At the time, BRM was “progressing” on two fronts, and while Rudd worked on the H-16, Peter Berthon and Weslake were designing a V-12. That project eventually fell apart, though the V-12 came back to replace the H-16, but it was sadly typical of BRM’s divide and rule philosophy, though it was seen at the time as “hedging one’s bets.” The Berthon/Weslake alliance over the 4-valve V-12 was a highly political action within the BRM organization. While the two projects were running, the notion was that the most successful would go in the GP car, that V-12s would be built and sold as sports car units, and that H-16s would be built for the Lotus team.

The H-16 engine was first run in February 1966 after sorting serious problems in getting the water from the lower to the upper cylinder heads. Then there were broken camshafts and ignition trigger disc drives, stripped teeth on the rubber belt drives for the injection metering units and endless problems with severe vibration in the crankshaft. Though the H-16 was longer and wider than the V-8, it was only marginally so, and it was lower, so the new car had a center of gravity two inches lower than the 1.5-liter car. Because there had to be a doubling up of the accessories, the compact unit soon became quite bulky for the chassis, and that is when the idea that it should be a stressed member occurred…really there was no other choice. The bulk was kept as minimal as possible and the resultant appearance was rectangular rather than square!

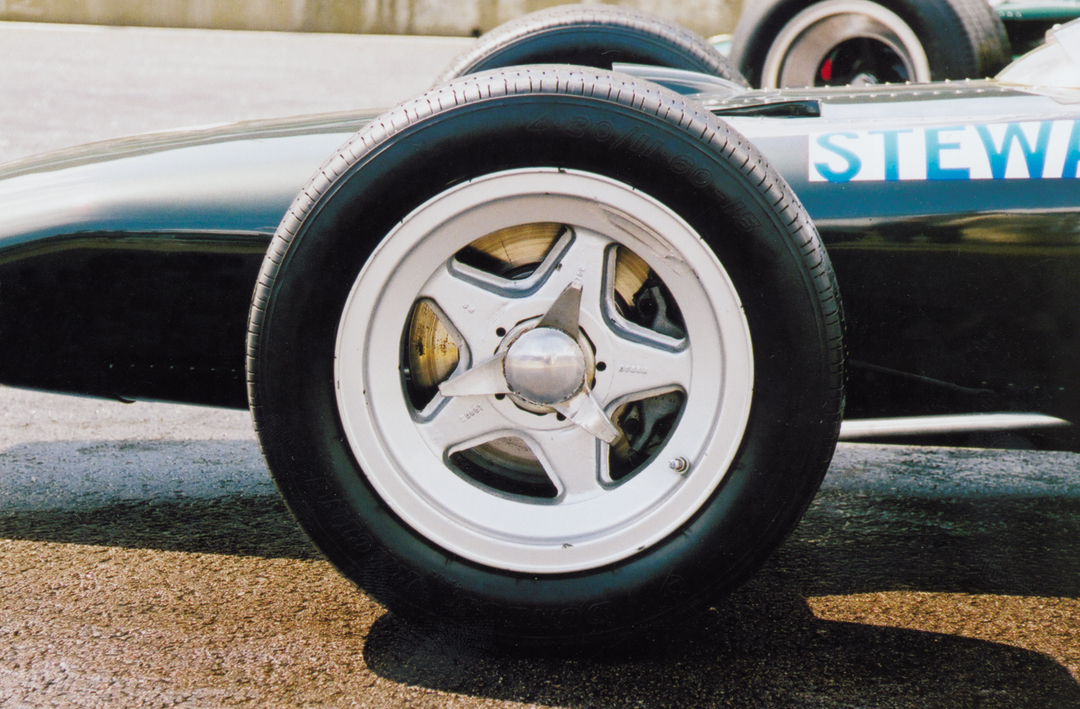

The rear suspension had been strengthened considerably and there were new cast wheels. The 6-speed gear-change was operated by aircraft cables, and in early testing these had a habit of stretching and thus the driver (Graham Hill) complained of not being able to find the gears, which ultimately resulted in over-revving. This arrangement was then changed to use a more conventional sliding pushrod control. The engine was overweight, and much work was done to shed weight wherever possible: the clutch was redesigned and lightened and weight was taken out of the brake calipers, which, in hindsight, was probably a mistake.

Photo: Ferret Fotographics

When Rudd first drove the new car, which was what he traditionally did, he found it surprisingly quiet at the exhaust end and surprisingly noisy in the engine department. He described the engine sound as being something of a “frenzy” and there was noticeable vibration, which was later substantially reduced, and as I discovered, the “frenzy” became limited to running when cool, as it took the oil to circulate. Nevertheless, the exhaust noise was far less dramatic than expected. In its early form, the engine was producing a disappointing 410 bhp and was capable of running up to 10,500 rpm, a figure much lower than had been predicted…by some 3000 rpm. At the early stages, revving beyond 10,500 rpm would result in the inertia weights, which had been bolted and welded over the crankshaft balance weights, to fly off and destroy the engine!

The decision was made for the car to be entered for the 1966 Monaco Grand Prix, but to be used in practice only. Rudd had also been pushed into working on a 4.2-liter Indy engine for Lotus, so it can be seen how BRM always managed to find itself over-stretched. Jackie Stewart and Graham Hill raced the P61s to 1st and 3rd at Monaco and Hill stretched the gear cables in practice in chassis 8301 with the H-16, which was designated a Type 75. Back at Bourne, Rudd soon designed a tubular, universally jointed gear-change. Around this time, BRM delivered a “customer” engine to Lotus, where Colin Chapman was shocked to find the engine weighed 555 pounds plus 183 pounds for the gearbox and clutch, which had been mounted wrong way round!

Photo: Ed McDonough Collection

In order to correct the gearbox problems, it was decided to delay racing the H-16 until Monza. P8301 went to Spa for practice, as it did at Reims in July along with the new car P8302. At Monza in early September, BRM entered 8302 for Stewart and the 3rd new car, 8303, for Hill and brought 8301 for practice, while Jim Clark had the Lotus 43/H-16, which he managed to put on the front row, while Stewart and Hill were on rows four and five. Graham had valve failure almost immediately and Stewart had a fuel tank leak and then a misfire and was out on Lap 6, while Clark ran well until the gearbox broke. The Clark performance was heartening, but all the component failures were BRM, so BRM were apprehensive as they went to Watkins Glen in October, where the author was present to see Jim Clark give the H-16 engine its first and only Grand Prix win in the back of the Lotus while Stewart in 8301 had his H-16 fail on Lap 53, one lap after Graham Hill’s 8302 had the crown wheel and pinion break. However, Hill and Stewart were much closer to Clark on the grid this time, less than a second slower.

Clark had blown up one H-16 in getting onto the front row at Watkins Glen but was at the front in Mexico without a repeat. He was, however, out with another gear change failure…not a BRM piece this time…while Stewart retired from 3rd place in 8303 with an oil leak when the scavenge connection came off. Graham left his tenure at BRM with a broken camshaft as a souvenir of his BRM days and Surtees won the race in the unlikely but now speedy Cooper-Maserati V-12. BRM had used 8301 in practice to try some modifications for 1967. At this point Graham Hill could not see the H-16 coming good, while Stewart could, something he soon changed his mind about.

Revisions for 1967

Photo: Nick Loudon

BRM and Tony Rudd spent the winter trying to make the H-16 a better car. Rudd designed a new crankshaft, which reduced the vibration but an increase in power continued to find weaknesses in the gearbox. The decision was taken to build a new, lighter and more compact chassis…Type 115…but the car was still 250 pounds overweight and this meant considerable shocks were going through the drive train. By the time 1151 was built, it was now clear that BRM was unlikely to build more due to the pressure of other projects. The first chassis, Type 83, was built in 1966 with Type 115 a year later—this meant that there were 32 other projects in between!

The rear suspension was improved on 1151…the only Type 115 to be built, as it turned out. The top trailing link was omitted and a variable length lower transverse link was added. Larger rear brakes were fitted with bigger master cylinders, and the discs were ventilated. 1151 was a full three inches narrower than the P83. At the South African Grand Prix on January 2, 1967, Stewart and Mike Spence were in 8303 and 8302, as the new car was not yet ready. Clark and, ironically, Hill were in Lotus 43s…still with the H-16 engine so Hill hadn’t gotten away from it yet. All four of the H-16s overheated and retired with related engine problems while Pedro Rodriguez took the Cooper-Maserati to another win. Tim Parnell ran Spence in 8301 at the Brands Hatch Race of Champions where he was 5th, and he and Stewart did well in the heats at Oulton Park’s Spring Trophy in the same cars. Jackie Stewart put 8303 on pole for the International Trophy at Silverstone but the final drive broke on Lap 16. Spence managed 6th at Monaco in 8302 while 8303 practiced but Stewart raced an older car. Stewart and Spence had 8303 and 8302 at the Dutch Grand Prix where the Lotus 49-Cosworth appeared, and the new H-16 1151 appeared in practice only. Jackie Stewart had a role in convincing Alfred Owen to advance the work on the V-12 that BRM itself was now building and the car was subcontracted out to Len Terry while most development on the H-16 stopped, though it would be raced until the V-12 was ready.

8302 and 8303 were driven at Spa by Spence and Stewart and Stewart did very well to finish 2nd to Gurney’s Eagle while Spence ended up 5th. Stewart was in the lead and would have won had fifth gear not broken, with Gurney overtaking him and winning by over a minute. 1151 came out again in practice at the French Grand Prix, but Stewart raced a Tasman car to 3rd, while Chris Irwin took 8302 to 5th with Spence retiring 8303. At the British Grand Prix at Silverstone in mid-July, Stewart and Spence again raced 8302 and 8303 while 1151 had suspension problems in practice in Stewart’s hands and was sidelined once again. Both P83s retired in the race.

Stewart made 1151’s race debut at the Nürburgring for the German Grand Prix in August. While the V-12 had its first test at home and was lighter and more powerful than the H-16, Stewart and Spence (8302) and Irwin (8301) were getting incredibly high in the air over the Ring’s bumps. Stewart’s 3rd on the grid was a full 11 seconds off Clark’s pole. Irwin finished 7th while the crown wheel and pinions broke on the other two cars from too much jumping. This was an inauspicious debut for the new 115 chassis.

Sheldon and Rabagliati report that the H-16 engine type in 8302 and 8303 was Type 80 rather than 75. Rudd says he was designing a lighter weight H-16 at the time so this must have been it, though it isn’t mentioned. I asked Richard Attwood and noted BRM expert Rick Hall what the difference between the 75 and 80 was and they both replied, “5!” Nevertheless it didn’t work. The BRM V-12 appeared in the back of a McLaren in Canada. Stewart drove 1151 again at Monza, qualified 7th and retired on Lap 45 when the engine blew. He qualified 10th in 1151 at Watkins Glen, got to Lap 72, when the fuel metering unit went. Stewart was then only 12th on the grid in 1151 in Mexico behind Spence in 8302, and a broken crankshaft ended Stewart’s days at BRM, as he then went off to Ken Tyrell and the Matra-Cosworth. When the author asked Stewart what his retrospective view of the H-16 was, he replied: “Well, I went to Ken, didn’t I?”

1151 made its final race appearance in period in Mike Spence’s hands at the South African Grand Prix on New Year’s Day, 1968. He was well down the grid, behind Rodriguez, now in the BRM team in the V-12 P126. Neither car finished the race. Rudd later said that he should have built the H-16 much, much lighter…and that if they had concentrated on the V-12, things would have been much different.

Driving the H-16

One of the P83 cars was turned into an F5000 machine, and one is in the Donington Collection, while Michael Burtt came into possession of the only 115 chassis, and has been using it sparingly for historic races.

When it came time to test this by-now venerable and revered machine, I approached it with considerable trepidation, because of its value and my perception that, based on history, it was going to blow up, or at best be an immensely difficult car to drive, and 16 cylinders would never all be working at one time. However, I had neglected to realize the impact of Hall and Halls’ influence on this car, where they had used their great BRM experience to do more sensible improvement to the car than had been done in period.

The test took place in a rather odd location, at Rockingham Motor Speedway in central England, where there is one of Europe’s two oval speedways, with a combination road course as well. Sadly, the attempt to get oval racing working in Europe failed but it left this great circuit, and I was about to use both the road circuit and the oval to try out the BRM; interesting in the light of BRM’s attempts to develop an Indy car for Lotus.

Squeezed into the tartan-decorated interior…a Stewart remnant I believe…the car is pure time warp, and what restoration has been done is immensely sensitive. There is a small wrench taped to the steering wheel “for emergencies.” The rev counter reads to 12,500 rpm and there are a few other gauges…that’s all. As I mentioned, I was wary of the engine and to some extent the gearbox. When the starter went, however, my preconceptions were proved totally wrong. The H-16 burst to life with ease and revved away without a miss. Though it is noisy in a clattering sort of way until it warms up, there was no fuss at all. The gearbox is BRM 6-speed, with no reverse and no gate, so it was a question of feeling my way, and that proved to be very straightforward. A few warm-up laps saw the engine noise drop and the exhaust begin to echo off the walls of the empty stadium. The cockpit is comfortable, the pedals well spaced and there is no grappling about. It was at this point that I knew that I hadn’t really grasped what it was about the BRM that no one liked, as the braking was more than adequate, the handling very neutral, and the H-16 smooth in delivering the 400+ bhp. The answer was, of course, that it was its unreliability that they disliked. Stewart later admitted to the author that it handled well, and indeed at one point showed potential, but against the background of failure and all the other things going on at BRM, he could see it was never going to really work.

Later that day, I stepped from the H-16 1151 into the Lotus 49-Cosworth for our test drive of that car which appeared here last September. That was when I knew the BRM was heavy, and miles less responsive than the Lotus, which was twitchy and urgently wanting to break loose. That was the difference between the old and the new worlds in Grand Prix racing…the steady, conservative BRM approach was completely overwhelmed by the Lotus and the Cosworth. None of that, however, took away from the pleasure and privilege of driving a true legend. When I told Jackie Stewart that I was going to drive it he said “better you than me,” and I agreed. More recently, he asked if I enjoyed it and wasn’t too surprised when I said “yes.”

Oh yes, that third chassis type? I came across a vague reference to a Type 109 H-16. This had me spinning until I discovered that this was a factory-built exhibition car which never ran but is now living in Australia!

Chassis: Monocoque with engine as a stressed chassis member, magnesium skinned

Engine: 16 cylinders in horizontal layout, equivalent to two horizontally opposed 8-cylinder engines

Crankshaft: Two four-throw counterbalanced single-plane crankshafts

Bearings: 5 plain main bearings

Cylinder liners: Wet liners in two alloy combined blocks

Camshafts: 8 overhead camshafts driven by gear trains from nose of lower crankshaft

Bore and stroke: 68.5 mm. x 50.8 mm.

Capacity: 2998 cc

Valves: 2 overhead valves per cylinder

Compression: 12.5:1

Lubrication: Dry sump

Power: 420 bhp @ 10,750 rpm

Gearbox: ZF 6-speed

Tires: Dunlop Racing 5.30/15.00-15 on the rear and 4.30/11.60/15 on front with original BRM wheels

Resources

Thanks to Michael Burtt, Hall and Hall, and Rockingham Speedway.

Hodges, D. A-Z of Formula Racing Cars 1945-1990 Bay View Books, Devon UK 1990

Rudd, T. It Was Fun Haynes Publishing, Somerset, UK 1993

Sheldon, P. and D. Rabagliati A Record of Grand Prix and Voiturette Racing Vol. 8 St. Leonard’s Press, Bradford UK 1994