Harry Arminius Miller (1875–1943) was the greatest individual designer and builder of racing cars and engines of the 20th century, a statement I write advisedly, fully aware of the many brilliant individuals who have contributed to the sport of speed over the previous 100 years.

Harry Miller began his career as a riding mechanic with Buick’s Vanderbilt Cup team in 1906. He died in Detroit during World War II, after working on an engine for an ill-fated fighter plane being peddled to the Air Corps by Preston Tucker. In between, he built the fastest, most sophisticated and clearly the most beautiful racing cars ever to turn a wheel. One car that he built in 1928 held the one-lap record at Indianapolis for an amazing nine years. His 8-cylinder engines won at Indianapolis nine times between 1922 and 1933 and in 1930 he designed a 4-cylinder twin-cam engine that—only moderately updated and renamed “Offenhauser”—won at Indianapolis 32 times until racing politics did it in after its 1976 victory.

And Miller accomplished all that with a Los Angeles company based on a carburetor he invented, with a design staff of but two men, draftsman Leo Goossen and master machinist Fred Offenhauser. So talented was the Miller shop that in less than three months in 1931 he, Leo and Fred designed and built from scratch a complete new 16-cylinder speedboat engine for Gar Wood.

In the early 1930s Miller built two four-wheel drive Indianapolis racing cars for the FWD Company, manufacturer of heavy four-wheel-drive trucks. Mauri Rose drove one of them to 4th place at Indianapolis in 1936. This design would linger in Harry’s fertile mind.

The Miller-Ford

Miller’s business became tangled in the changed formula for racing at Indianapolis after 1929 and as a result, he struggled in the early years of the Depression, finally going bankrupt in 1933. However, by this time Harry was world-famous, even if he was broke. He left California and sought to regain his fortunes in the east. In Los Angeles, Fred Offenhauser, his shop foreman, picked up the pieces, mildly revised the 4-cylinder Miller engine and carried it on under his own name.

Miller first moved to New York City, where he had worked during World War I, and set up an office at 1560 Broadway where he designed V-8 and V-12 aero engines on the one hand and, at the same time, designed a team of 10 highly advanced racing cars for Henry Ford—cars Preston Tucker had sold Ford long before Miller had even begun to put pencil to paper.

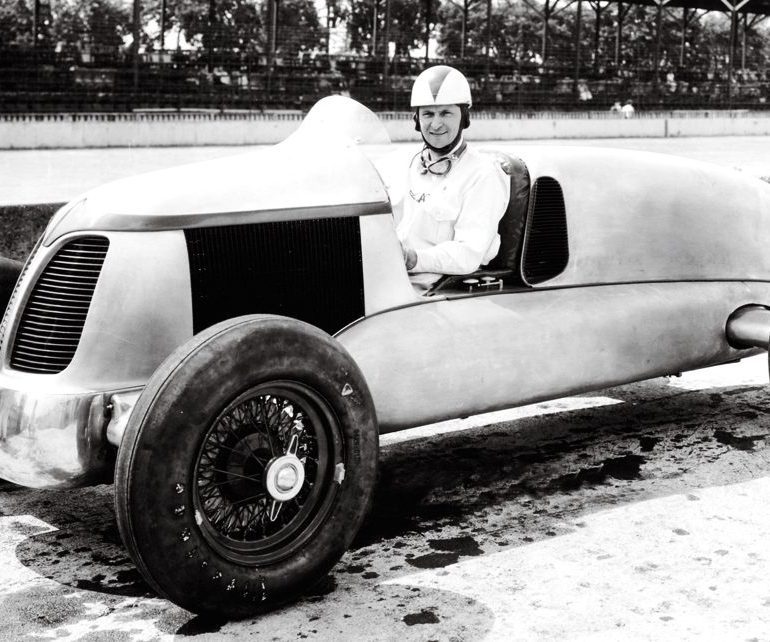

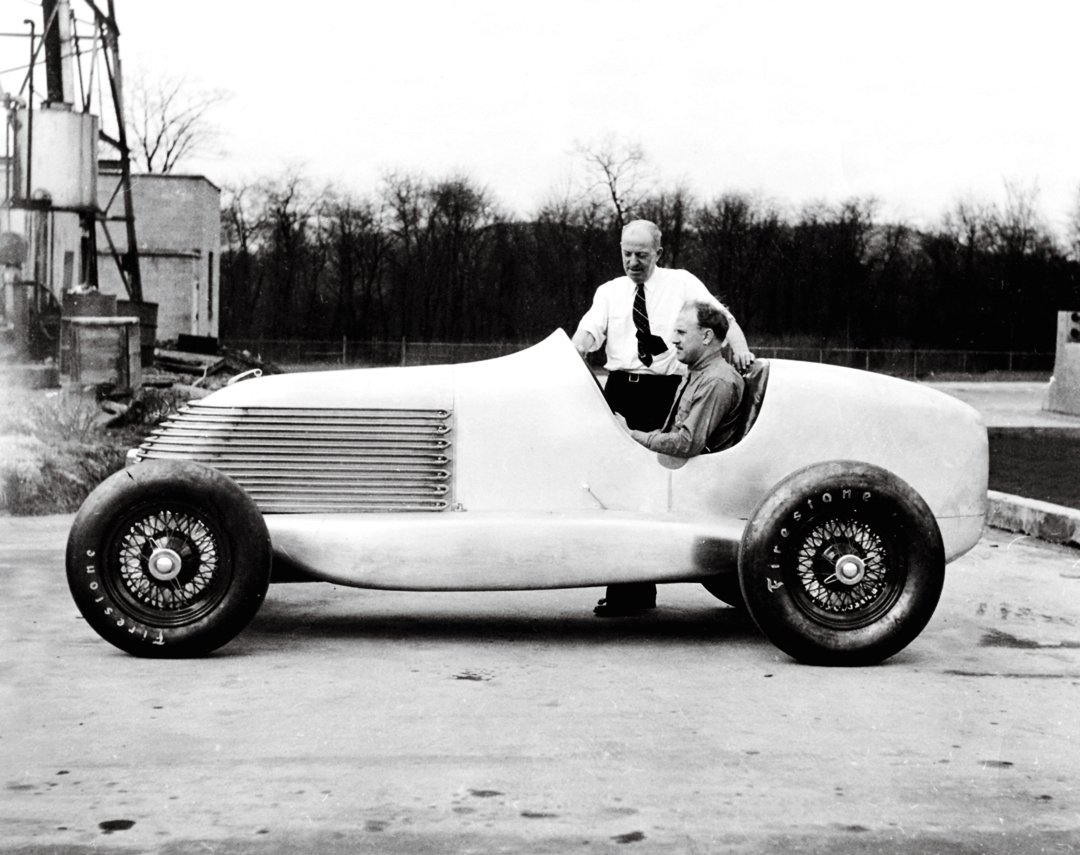

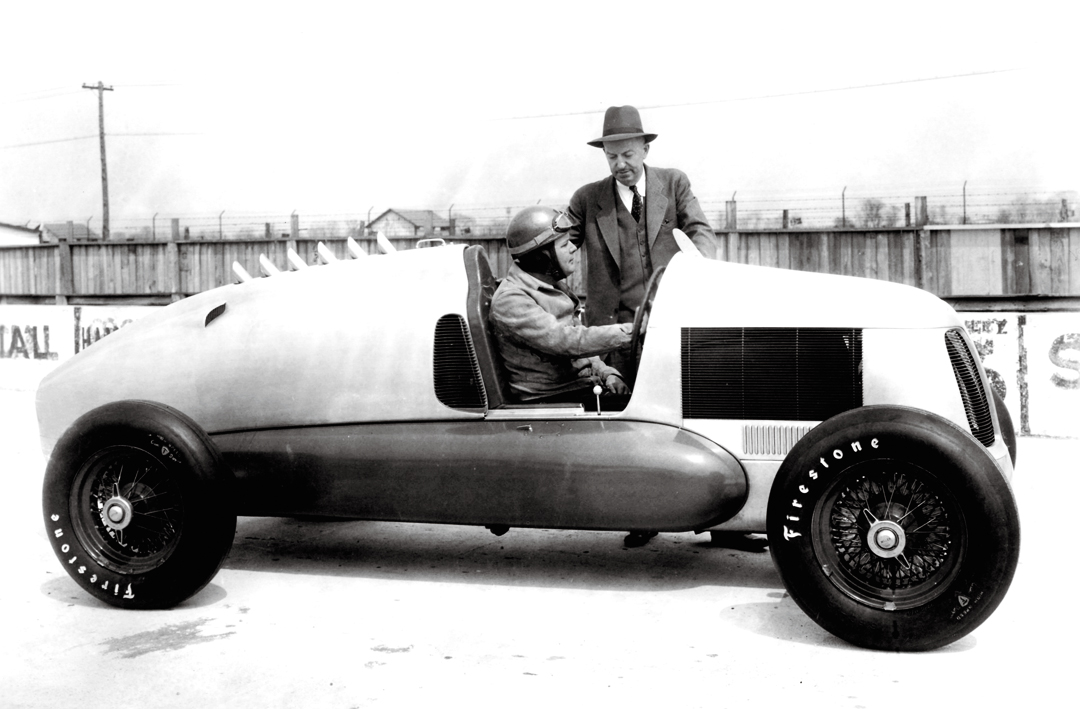

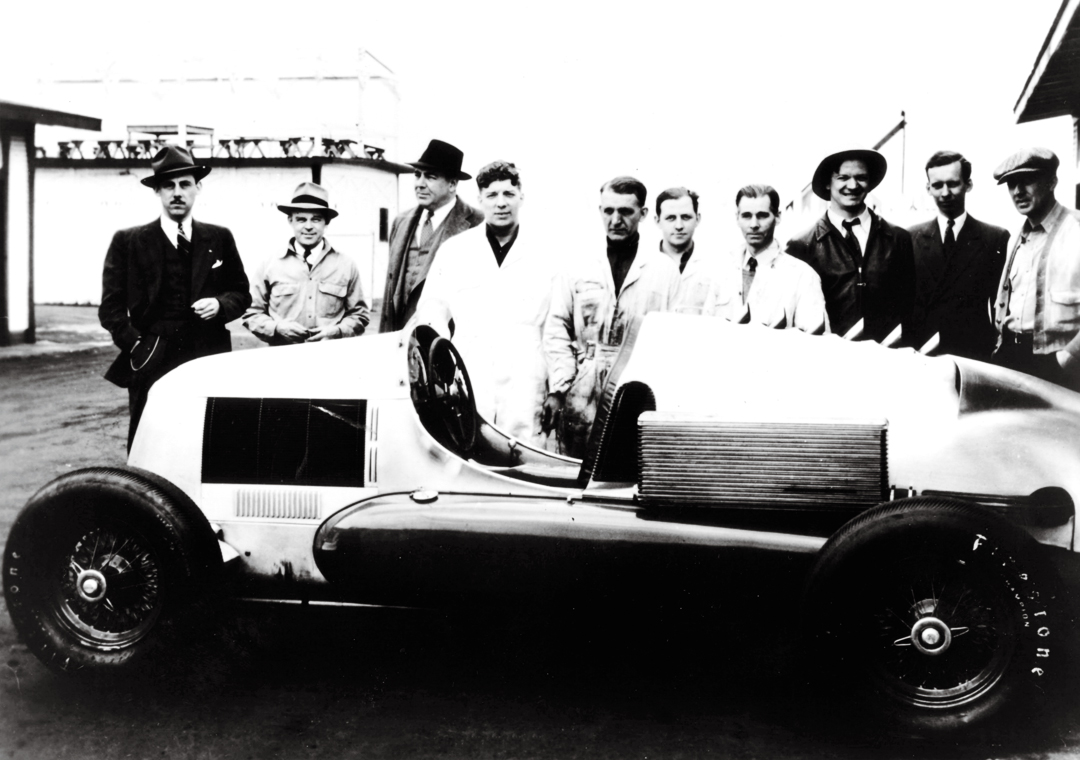

The 1935 Miller-Fords were aimed at promoting Ford’s new V-8 engine and carried slightly hopped-up flathead Ford engines that could only be competitive against the thoroughbred twin-cam Offenhauser engine if their chassis were light-years ahead of the competition. That they were, with front-wheel drive and low, aerodynamic lines that were far more modern than the standard racecars of the 1930s. Unfortunately, time was short and only four of the cars made it to Indy in time to qualify, though none had had thorough testing. All four cars fell out of the race with their steering “frozen” by overheating as their gearboxes had been bolted to one of the exhaust manifolds.

Next, Miller designed a speedboat engine for Gold Cup competition and was enlisted by Tom Darrin of LeBaron, the custom-car builder, to work on the design of a sports car. Miller had his draftsman, R.E. Stevenson, draw up a sporty little car that greatly resembled the current-day Plymouth Prowler. Automotive entrepreneur Roy Evans hired Miller and Hibbard to redesign the American Bantam car at the American Austin plant in Butler, Pennsylvania. Miller and Hibbard designed a beautiful car, but one far too expensive for the time and as a result it was never built. Instead, Miller put together a neat little four-wheel-drive job that greatly resembled what, four years later, would become the World War II Jeep, manufactured in the 1940s by Willy and Ford because the Bantam Company did not have the facilities to turn out the quantities the War Department required.

While Miller was at Bantam’s Butler plant, racing promoter Ira Vail asked him to design an advanced racing car for Indianapolis. Harry came up with a rear-drive, independent-suspension chassis, based roughly on his Miller-Ford design, powered by a 255-cubic-inch, twin-cam four but, unlike the barrel crankcase of Offy-cum-Miller, the new engine had its crankcase split at the midline of the crankshaft.

Miller gave the car the first disk brakes used in American racing, though unlike modern “spot” brakes his in 1937 were more like a hydraulically-activated clutch with pressure applied to the entire 360-degree surface of the disk. They were highly efficient at first, but because the brakes were closely shrouded inside the wheels, they tended to overheat and fade.

Butler was located in Western Pennsylvania, which led to the fact that Miller attracted the attention of James Drake, chairman of the board of the nearby Pittsburgh-based Gulf Oil Company. Drake looked at the Vail cars and persuaded Ira to sell the project to his very-well-heeled oil company as a means of advertising Gulf’s No-Nox Gasoline.

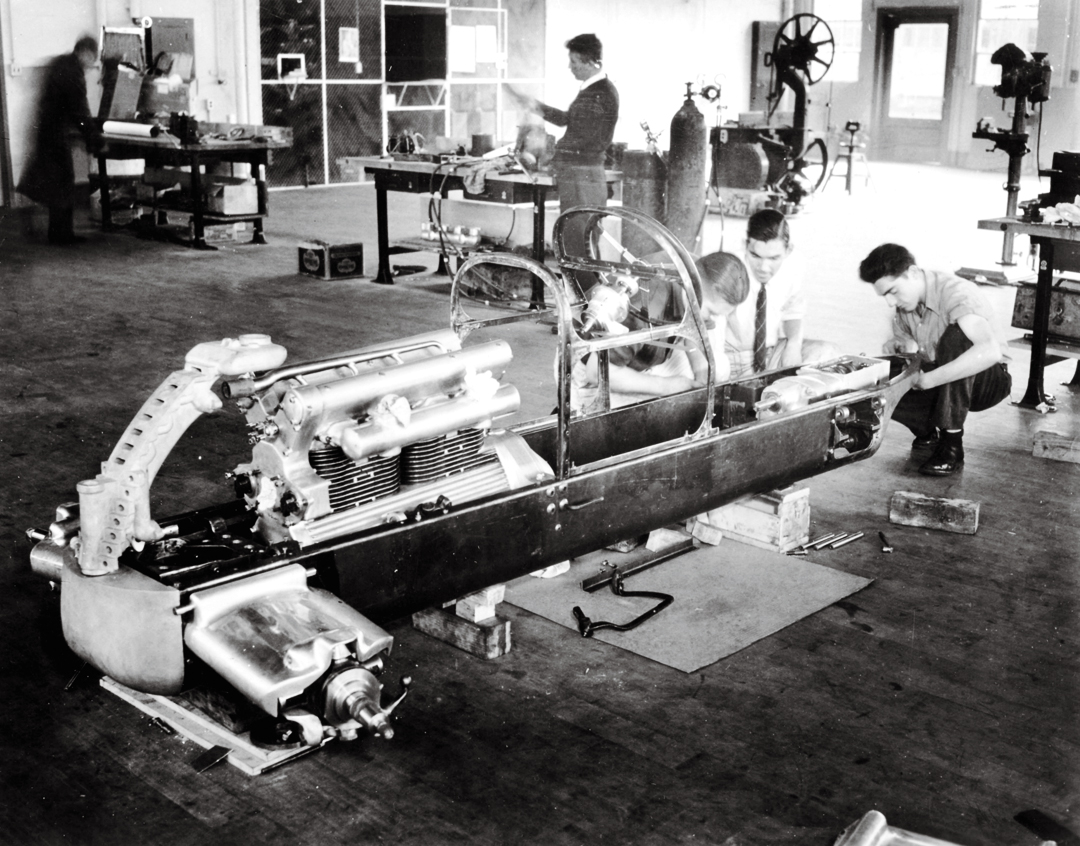

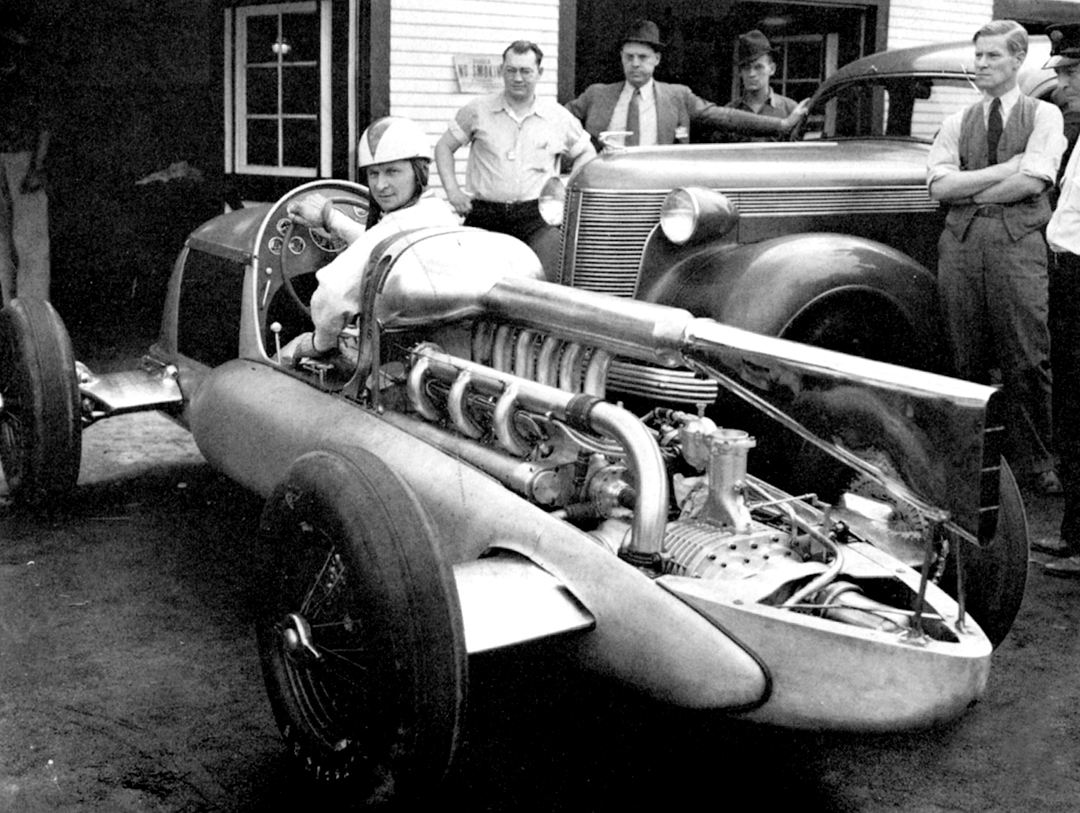

Soon the project was moved to the nearby Gulf laboratory at Harmarville, Pennsylvania, where the cars were completed. They were incredibly advanced and their engines exceedingly complex, particularly compared to the much-more-simple, 4-cylinder Offenhauser engines that were dominating American racing at the time. Unfortunately, the Gulf engineers and machinists were so impressed with the credentials of the great Harry Miller that they built what he dreamed up without much checking of his figures.

One of Harry’s ideas was to use as a radiator, coils of chrome-plated but unfinned copper tubing that curved around the nose of the car, somewhat in the style used on the British Supermarine seaplanes that had won the Schneider Trophy. What worked for 200-mile-an-hour aircraft didn’t necessarily work on 100-mph racecars, and thus the new Millers had overheating problems from the start. It was the kind of error that in Miller’s old days, Leo Goossen would have caught. The cars and engines were also difficult to build, the parts hard to machine, a problem Fred Offenhauser would have dealt with before the patterns went to the foundry to be cast.

Interestingly, all these problems were correctable save one—for advertising reasons Gulf insisted on using its 80-octane pump gasoline in the cars. By then racers were using a great deal better fuel on the track. Many were burning methanol and those still using gasoline were doping it with great quantities of tetraethyl lead and other additives. That decision by Gulf essentially doomed the Gulf-Millers in competition.

Miller took the cars to the mile dirt track at Langhorne, in Eastern Pennsylvania, to test them and immediately discovered the overheating problem. As a result, the array of tubing was replaced by conventional radiators mounted on each side of the hood. A normal radiator could not be easily put inside the nose of the cars because the design had a curved, cast aluminum beam down the centerline, though much later that would be changed.

The four-cylinder cars were entered at Indianapolis in 1938 with veteran Billy Winn as their driver, but he was unable to get either one into the lineup. The cobbled-together cooling system still overheated and there were other problems that kept Winn from reaching qualifying speed, in that year just over 116 miles an hour (far slower than Leon Duray had driven his Miller in 1928).

The four-cylinder Gulf-Millers never raced again. Preston Tucker acquired the engines, which he used in a prototype of a military landing craft to be built in New Orleans by Andrew J. Higgins. After WWII, they were bought by a collector in Chicago who kept them for many years, finally selling them in 2003 to the late Chuck Davis, who, using fragments of the chassis, built a reconstruction of one of the cars, a monumental job completed just before Chuck died in 2005.

Surprisingly, even before 1938, Gulf had given Miller the go-ahead to design an even more ambitious car, a six-cylinder, supercharged pinnacle of racing technology. Harry let his imagination run wild, and Gulf, still starry-eyed over what the great man might conjure up, let him have his head.

Beginning of the End

While lesser lights were re-working the Gulf four-cylinder cars in the fall of 1937, Miller began work on what would be the final cars and engines of his brilliant career. No experienced racing mechanic, no Leo Goossen (a draftsman of automobiles for three decades), no long-time master machinist like Fred Offenhauser would cast an eye on his plans to startle the racing world with what the late Griffith Borgeson would call “the cars from Mars.” No, Harry Miller would design the ultimate racing car on a very clean sheet of paper.

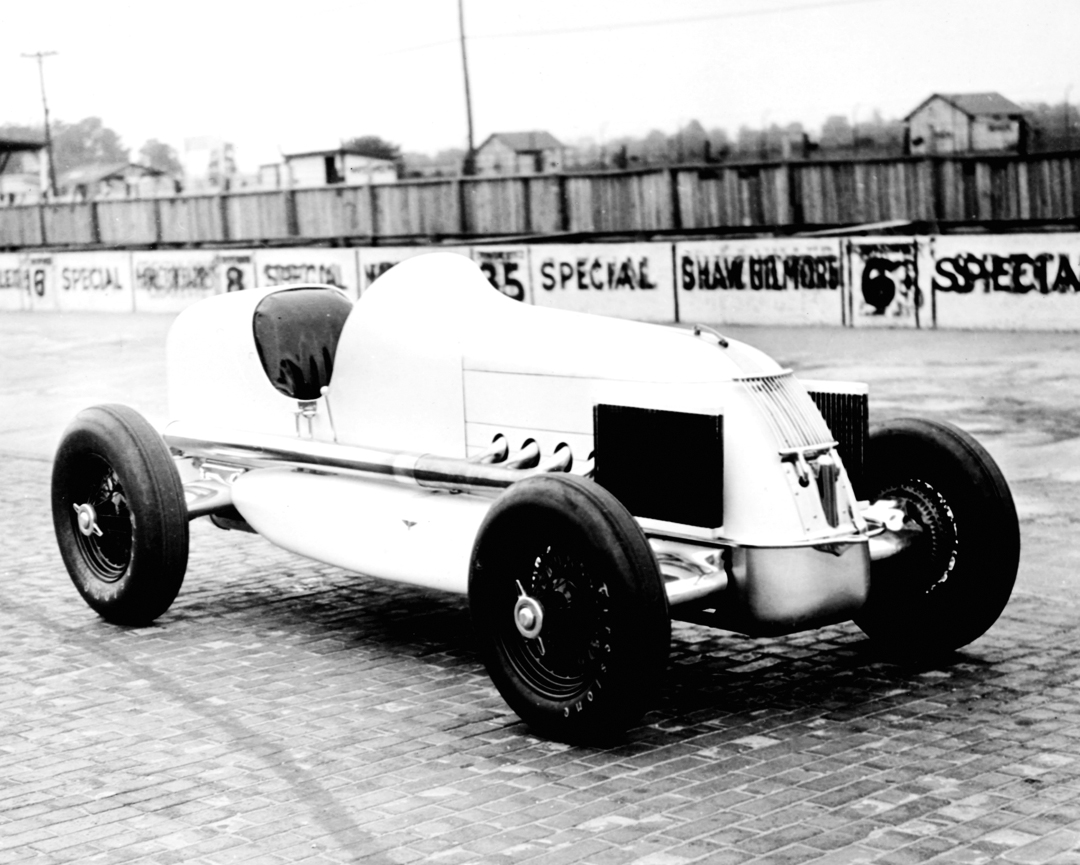

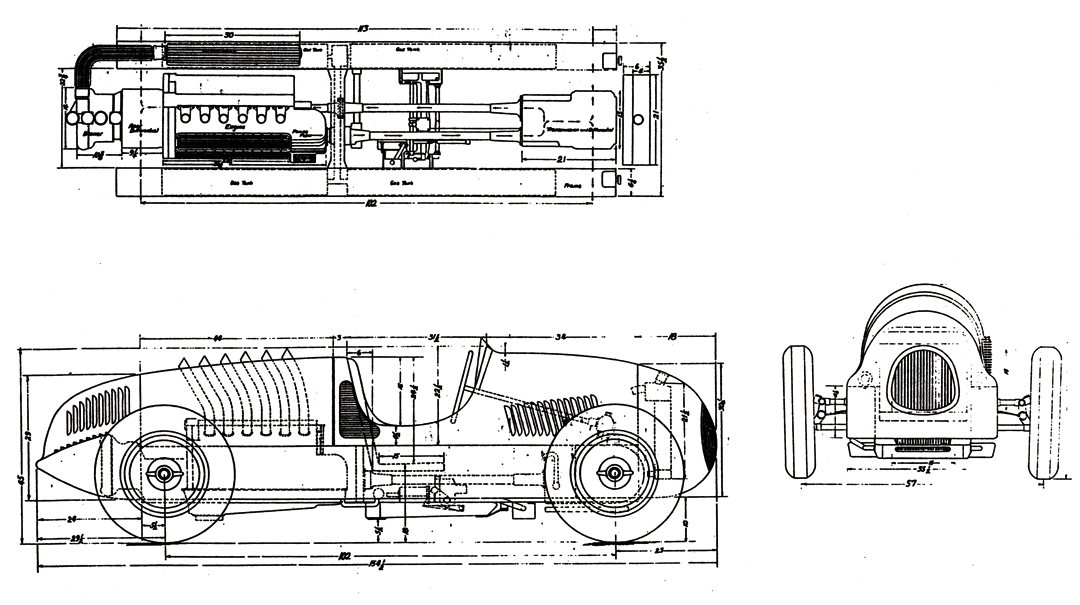

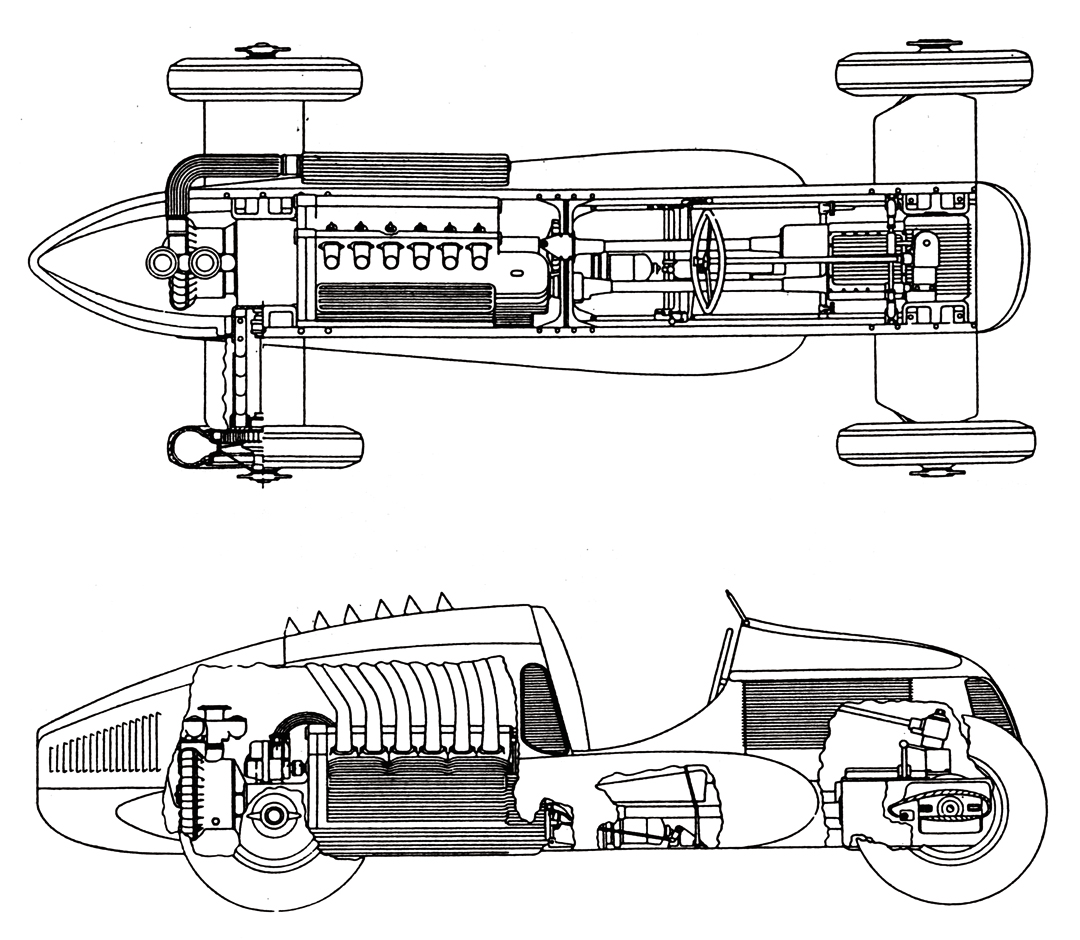

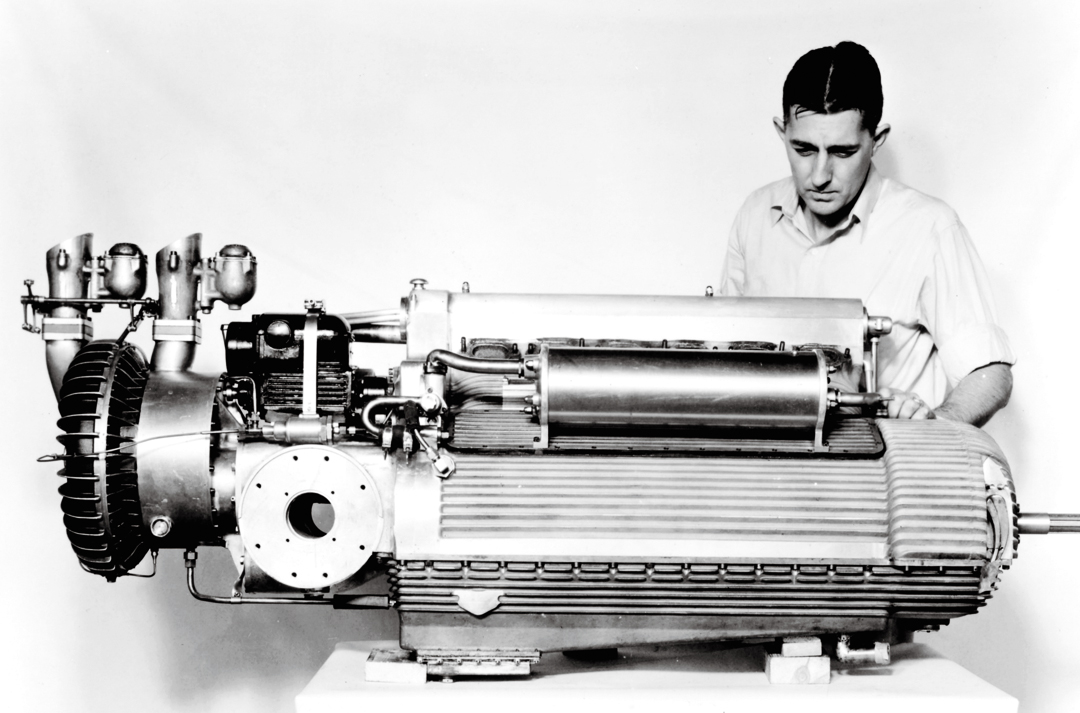

The last Gulf-Millers—three were built—had four-wheel drive, disk brakes, highly advanced suspension and a supercharged six-cylinder engine mounted in the rear of the vehicle. The only racing man present at the creation of the final Miller was Riley Brett, a journeyman mechanic of some talent, but without the prestige to sway the master. Against Brett’s advice, Miller designed a tall car that forced the driver to sit conventionally over the driveshaft.

The four-wheel-drive system differed significantly from the layout of the earlier Miller four-wheel-drive cars of 1931–’32 and was far more complex than it needed to be. Miller’s biographer, the late Mark L. Dees, described it as “a marvelous example of how something out of Rube Goldberg’s nightmares can be made to look sophisticated, and to work reliably if it is executed well enough in every detail.”

There were change gears in the power transfer box, a differential in the front axle, one in the drive line between the axles and a third in the rear axle housing that was integral to the engine, from which was hung at the extreme rear, the supercharger. The first blower was a Roots-type, more suited to road racing than to a speedway like Indianapolis. Its carburetor was a special design by Miller flowing into siamesed downdraft intake throats. The exhaust system was double-ended, designed to allow the slipstream to help draw out the exhaust gas. The engine was brought to life by an aircraft “Coffman” starter that used a blank shotgun shell to turn it over.

At Indianapolis in 1938 the one car that was entered was plagued with problems, including difficulties with the oiling system, as the oil foamed badly in the dry-sump tank. The engine, running on Gulf pump gasoline, overheated and was down on power.

Back at Harmarville, the exotic exhaust system was replaced by six short, curved stacks extending from the top of the body. The Roots supercharger was replaced by a more conventional centrifugal blower with a planetary drive and the blocks were re-cast to provide individual intake ports.

Gulf took the three cars to Indianapolis in March of 1939 for extensive testing with Eddie Offut, an experienced and practical racing mechanic to help work out most of the more obvious bugs. Veteran driver George Bailey qualified one of the Gulf-Millers in the 6th starting position at a respectable 125.8 mph. The driver of the second car, Johnny Seymour, hit the wall in practice and his car was destroyed by the subsequent fire, though Seymour was uninjured. Zeke Meyer drove the third Gulf-Miller but was unhappy with its handling and did not attempt to qualify. In the race, Bailey ran with the leaders until the engine lost a valve spring and swallowed a valve on lap 46.

Dark Days

During the summer of 1939, Miller and Gulf came to a parting of the ways. Harry was not a man to accept the organized ways of a large corporation and, in his way, he had other plans afoot.

Offutt took over the development of the racing team and continued to work on engine performance. According to test figures from the Gulf laboratories, a dynamometer run in November 1939 produced 243 horsepower at 6,850 rpm on 80-octane gasoline—a far cry from the 400 horsepower Art Sparks’ Thorne “Little Six” of the same displacement was getting on alcohol fuel at the same time.

Gulf took the two surviving cars back to Indianapolis in 1940, and in practice, Bailey hit the wall, one of the exposed side fuel tanks (Miller’s Gulf cars carried their fuel in airfoil-shaped tanks on each side that were capable of providing downforce) exploded and he burned to death. The American Automobile Association’s Contest Board, which controlled all things at Indy, demanded that Gulf withdraw the cars until the fuel tanks could be relocated.

That summer, seeking to salvage something from the disaster, Gulf took the cars to the Bonneville Salt Flats where they were run for class speed records in wide-open spaces where there was nothing to hit should a driver lose control. Driver George Barringer began test runs in early July and quickly found that the 4,200-foot altitude at Bonneville was killing the engine’s power. Higher-compression pistons were installed (6.24:1 for the No-Nox gasoline Gulf was using) and a faster-turning supercharger mounted on the engine. There were other failures, some repaired at the Bonneville base at Wendover, Utah, and others requiring more complex work in Los Angeles.

Finally, at dawn on July 30, 1940, Barringer gunned the car both ways through the measured mile at 156.965 miles an hour. Barringer came back a day later, after a few more tweaks, and turned the mile at 157.498 mph, giving him an American record for a 180-cubic-inch car. His 5-mile mark of 158.207 constituted an international Class D record for that distance.

Gulf had Barringer continue to 500 miles on a 10-mile circle laid out on the salt for Ab Jenkins’s Mormon Meteor and set an international 500-mile class record of 142.799 mph. Gulf repeatedly refused to allow use of alcohol fuel to boost the performance.

Back in Harmarville, Offutt oversaw the replacement of the external fuel tanks with new ones, inside new frame rails. Journeyman Indianapolis racecar builder Herman Rigling built new bodies to accommodate the redesigned chassis.

Gulf returned to Indy in 1941, only to find that Rigling’s bodies were aerodynamically unsatisfactory, their drag slowing the cars compared to their 1939 speeds. Observers felt the Rigling bodies were simply ugly, but ugly doesn’t count at Indianapolis if you go fast. On the Gulf cars they had neither beauty nor speed.

Nevertheless, both cars qualified. Barringer put his in the field 16th fastest at 122.299, while Al Miller drove the second car, qualifying 13th fastest at 123.478 mph. On race day, however, leaking gasoline fumes from the Gulf garage were ignited by welding sparks from the next bay, destroying Barringer’s car and burning down half a block of Gasoline Alley, delaying the start of the race by two hours. Several crews lost tools, Frank Kurtis among them.

Miller’s car survived to finish 28th when the transmission linkage failed on lap 14. The fire may have cost Wilbur Shaw a fourth Indy win, as a faulty wheel was installed on a pit stop and subsequently collapsed. It had been marked “DO NOT USE,” but firemen fighting the fire washed off the marks.

World War II halted racing in 1942 and by 1946 Gulf had had enough. The company sold the surviving car to Barringer. He re-sold it to Preston Tucker who entered it at Indianapolis as a promotion for his rear-engined passenger car, the Tucker Torpedo. Barringer qualified it at 120.628 mph, even slower than it had turned in 1941. In the race, the transmission failed again, on lap 27. Barringer was subsequently killed in another car at the Lakewood track in Atlanta, Georgia, in the same dust-plagued race in which 1946 Indy winner George Robson died.

Clay Ballinger entered the Tucker Torpedo at Indy in 1947 with Al Miller driving and the car qualified at 124.848, the best speed a Gulf-Miller ever achieved at the Speedway. The car ran 33 laps before the magneto failed. At Indianapolis, in 1948, Miller was driving in practice when a rod failed, destroying the crankcase of the last Gulf-Miller six.

Gulf Remains

The surviving Gulf-Miller four has been restored in California. The owner of the original engine refused to sell it, so it is powered by one four-cylinder bank of the L-510 aircraft engine Miller designed for Preston Tucker’s XP-57 pursuit plane project. The engines are nearly identical, though the L-510 consisted of two supercharged dual overhead cam fours.

Harry Miller continued to work on the L-510 after the Air Corps pulled the plug on Tucker’s airplane, hoping to put it into another aircraft or a boat. He also designed a completely different flat-twelve cylinder engine for Walter Christie for a “combat car.” Despite support from George S. Patton, who was on the evaluation committee, the Army rejected Christie’s design and Walter went on to sell his patented design for a tank suspension system to the Soviet government for its famous T-34 tank, the best armored vehicle of World War II.

Before he died, Chuck Davis had his restorer, Dave Hentschel, build a recreation of the Gulf-Miller four from bits and pieces, and one of the original engines.

The last six-cylinder Gulf-Miller car now rests in the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum, a poignant monument to Harry Miller and the hubris of his later dreams—and next to his far more successful racing creations of the 1920s and 1930s as well as the plain, perhaps even mundane but highly successful four-cylinder Offenhausers that dominated the Speedway for three decades.