Goodwood Lady

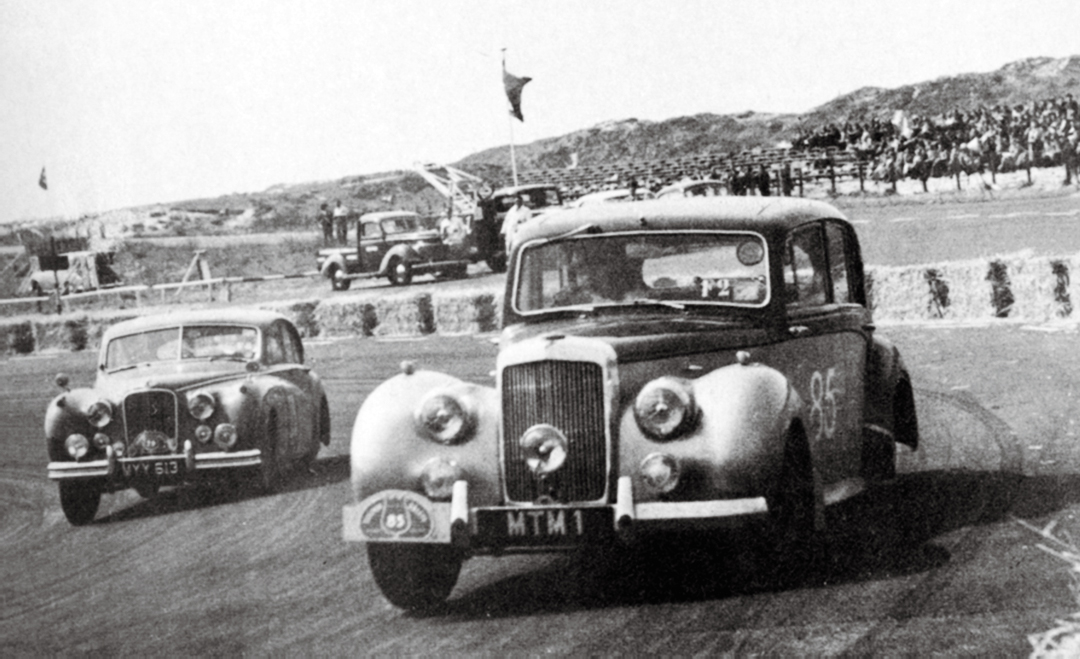

At the 2004 Goodwood Revival, a most unlikely machine quickly became the large crowd’s favorite as Ivan Dutton and the late Gerry Marshall pedaled Dutton’s rather majestic 1954 Alvis Grey Lady to a 2nd and 4th in the two heats of the St. Mary’s Trophy race. Not only did the car and drivers perform spectacularly, but this was the Alvis’s race debut. We were very pleased when Ivan agreed to bring the car back to Goodwood for us to have a serious opportunity to examine it at close quarters.

Alvis—A long, racing pedigree

The very first Alvis, the 10/30 four-cylinder, was produced in 1920 by the Coventry, England firm T.G. John Ltd., which had been founded the previous year. The new car’s designer, one G.P.H. de Freville took a silver medal at the Edinburgh trial. A few weeks later another 10/30 took fastest time of the day at the Rhiwbina hill climb in Wales, while company director T.G. John himself competed successfully throughout 1921 and 1922 in hill climbs and trials. Major C.M. Harvey was an Alvis-works driver in 1921 and he won two races at a Brooklands’ meeting which was something of a test for an attempt at the Coupe Internationale des Voiturettes at Le Mans. Racing had been taking place at Le Mans sometime before the 24 Hours started in 1923. A modified car was in 4th at that event when a cracked sump forced retirement.

That was the start of a long-term commitment to British and international competition which continued for another 30 years. While the 10/30 and 11/40 models took part in hill climbs and trials in 1922, the following year saw the debut of the 12/50 with its four-cylinder 1,490-cc, 50-bhp car in a number of sprints. The name of the company had now been changed to the Alvis Car and Engineering Company. Engineer and designer G.T. Smith-Clarke developed two 12/50s with streamline bodies, a higher compression engine and lighter parts for the major 1923 Brookland’s 200 Miles Race meeting. Major Harvey had his best result when he won the prestigious race for Alvis. Similar cars did well in that race in 1924, while a single-seater had also been built and considerable advances were being made with front-wheel drive. One of the 1924 Brooklands cars was used to set 39 records at that circuit and some of those British records stood until the 1960s. For 1925, front-wheel drive had been improved and was to feature in all then-current Alvis competition cars. A 12/50 with duralumin chassis appeared at the Kop hill climb two months before the American Miller FWD raced at Indianapolis. Harvey took the Alvis to a class win at the Shelsley Walsh hillclimb running unsupercharged, and finished 2nd overall to Henry Seagrave’s blown Grand Prix Sunbeam. For 1926, a straight-eight engine replaced the four-cylinder, still with 1.5-liter displacement. Harvey’s car crashed in the Brookland’s 200 and the second car retired. The engines were redesigned for 1927 with DOHC layout, but the Grand Prix cars were not successful and Alvis decided to concentrate on using their limited funds on sports car racing, where they were much more successful.

The year 1928 saw Alvis take 6th and 9th overall at the Le Mans 24 Hours, winning the 1.5-liter class with a four-cylinder sports car, and then took 2nd at the Ulster TT. Other cars set even more records at Brooklands. The straight-eight returned in 1929 in both sports car and single-seater form and a number of additional records were set. In 1930, the final year for a works racing team, they took the first three spots at the Tourist Trophy in the 1.5-liter class. With the auto industry in Britain experiencing serious financial woes, racing was left to privateers like Michael May to compete throughout the period right up to the outbreak of the war. May won the 1939 Irish Grand Prix at Phoenix Park in Dublin…the only Grand Prix win for an Alvis. In the UK, the Dunham family had begun a long association with Alvis cars. Dunham and Haines of Luton were Alvis agents from 1921 and they started racing a beam axle Speed 20 in 1932. They then built a lightened 12/70 in single-seater form and C.G.H. Dunham won the Brookland’s Outer Circuit Trophy in 1939. That car set the fastest lap in the last-ever Brookland’s race. Dunham won the Manx Cup in the car in 1951. After the war, Alvis sports cars appeared at Le Mans and new 3-liter cars ran in production car races and rallies in the early 1950s.

The Grey Lady

During the 1930s, the Speed 20 was the Alvis Company’s most important car, able to challenge Rolls Royce in sales. The company had started in very modest circumstances and by this time was very much at the high end of the market with numerous quality models including the Firefly, the Crested Eagle and Speed 25. Many people thought the Speed 25 was the best British pre-war car. As WWII drew nearer, Alvis was seriously involved in producing military vehicles for the Ministry of War. This made the firm a major German bombing target and the original car factory was destroyed by a Luftwaffe attack in November 1940. All production had been moved to another Coventry factory so Alvis was able to continue working throughout the war. The company had also become a major aero-engine supplier and built the Merlin engines for the Lancaster bomber. They also produced armored vehicles, and after car production ceased in the 1960s, Alvis continued to specialize in lightweight tanks and special military equipment.

Postwar car production for Alvis had become mainly a prestige activity, resulting in the car division making no profits after 1948. The TA21 model was produced for the 1950 Geneva Motor Show, and while plans were being discussed for an “upcoming” 8-cylinder car, the TA21 used the straight-six engine and evolved over the next few years, with the 8-cylinder never appearing. The TA21 had all new mechanicals, and was in fact a brand-new car, but it had a body that was some 10 years out of date. Essentially the TA21 was, outwardly, a prewar TA14 with headlights smoothed into the fenders and a better-looking rear section. Mulliner built the body with less wood in the construction than earlier models. It was stiffer than the TA14, and the TA21 was mechanically conventional, with independent front suspension and unequal length wishbones, telescopic dampers and a rubber-mounted antiroll bar. Alvis’s new hydraulic braking system operated four-wheel drums.

The car’s most notable feature was the latest 2,993-cc engine, an in-line six with seven main-bearing bottom end and a highmounted cam driven from the rear of the crank by a Duplex chain. This engine had good low and mid-range torque, as well as positive top gear performance. It produced a modest 86 bhp with a single carburetor. This was increased to 93 bhp with twin Solex carbs in later models. The TA21 could manage 90 mph—one of the few British cars able to do so at the time. In 1952, the TA21 became the TC21 with standard twin carbs. It also had a larger fuel tank and smoother bodywork. While traditional Alvis owners liked the handling and top-end power of the TC21 with its quality interior, sales were limited by an essentially old body shape, a relatively high price and increased purchase tax. With the intention to produce a V-8 by 1955, it was important that Alvis kept customers and dealers as happy as possible until the new car arrived. Thus for 1953, Alvis announced a higher-performance model, the TC21/100, which was known more popularly as the “Grey Lady.”

The Grey Lady featured a higher 8.2:1 compression ratio, an improvement over the 7.2:1 of the TC21. This produced 100 bhp and 100 mph, thus the title TC21/100. Alvis also decided to tweak the “ordinary” TC21 to produce the same power output but the two cars had different axle ratios. The Grey Lady had a number of interesting options including Dunlop center-lock wheels and twin bonnet scoops for better breathing (these scoops also helped reduce engine temperature.) Some, but not all, TC21/100s were badged as Grey Lady, for reasons that are not apparent. Doors and windows and other body elements were tidied up in 1953 to make the rather heavy car look a good deal sleeker. Reviews of the new car were very positive, the 100-mph capacity welcomed in a postwar world of many dull saloons. The Grey Lady was pretty impressive in top gear from 10 to 100 mph. Some 400 Grey Lady models were built by the end of 1954, but the end came when Mulliner announced it would no longer produce bodies for Alvis, switching loyalty to Standard-Triumph while the company’s other body supplier, Tickford, went to Aston Martin. Thus production ended for this now-aging model. The Swiss firm Graber supplied bodies for a new but not very successful TC108 saloon, and everyone thought the Alvis car days were over. In fact, the three-liter engine powered a range of Alvis cars for another ten years.

The Grey Lady in Racing

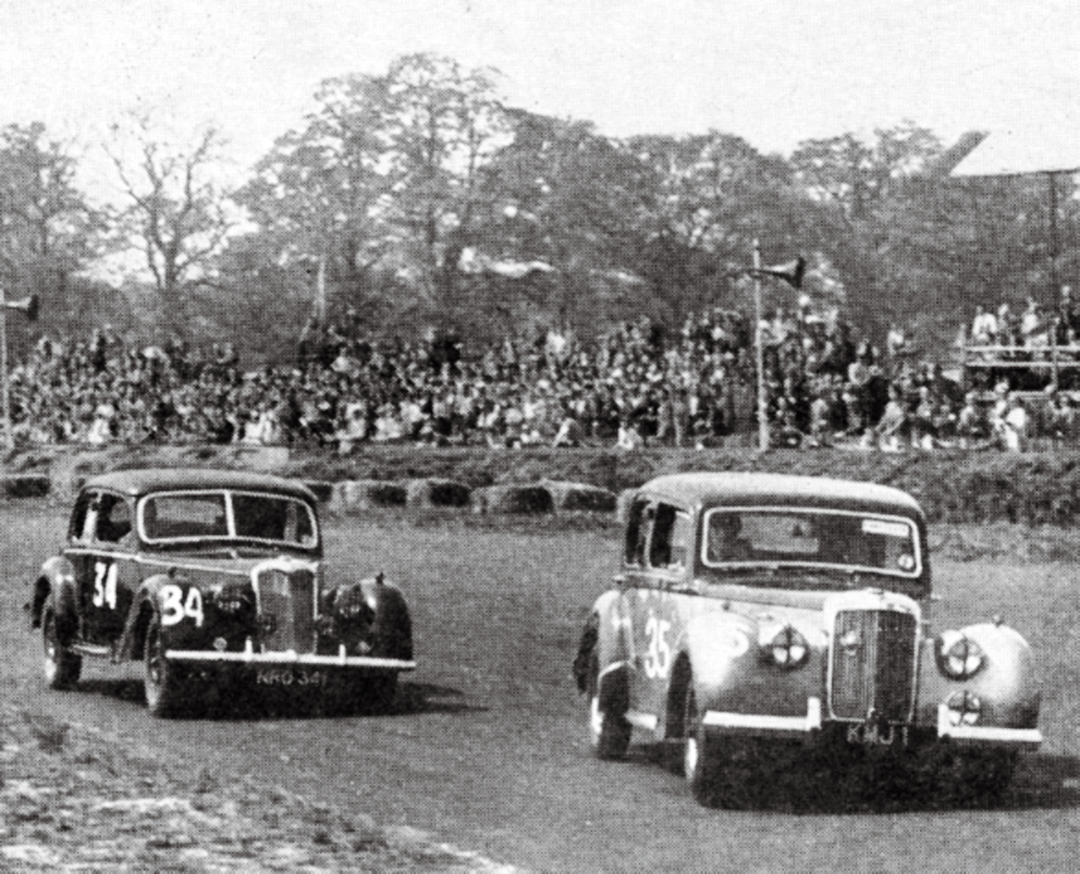

Motor racing prospered in postwar Britain. As we mentioned earlier, Dunham and Haines were Alvis dealers and entered races over a long period. One C.G.H.F. Dunham, better known as Gerry, was a very active competitor. He raced the family Alvis in several Manx Cup races, as well as a DHS-Rover in the Silverstone International Trophy and the Dundrod TT in 1953, and in races at Goodwood and Crystal Palace in 1954. This special became the DHS-Alvis in 1954, when Dunham raced it at a second meeting at Crystal Palace. He was also an enthusiastic touring-car driver in the early 1950s and brought the Dunham and Haines-entered Grey Lady in many events of the period. While competing in the 1953 International Trophy race at Silverstone, he was entered in the saloon race in the Grey Lady.

This race was headed by Stirling Moss in a Jaguar Mk VII and featured Alvis, Riley, Bristol, Jowett Javelin, MG, Morris Minor, Austin A40, Panhard, Renault and Simca Aronde cars. Future F1 constructor Harry Ferguson dropped the Union Jack for a Le Mans start, and a huge number of cars silently glided away with Stirling Moss quickly in the lead. Squealing tires were heard over the hum of silenced exhausts through Copse Corner, while Moss came through first, having just crashed his C-Type Jaguar in practice for the sports car race. Then Gerry Dunham in the Grey Lady was next ahead of Grace’s Riley 2.5 followed by a pair of Bristols and then a long string of cars. Vic Derrington was at the rear in a stately 750-cc Renault.

The best battle of the race was between the Riley and the Alvis of Dunham, which was out-handled by the Riley but Dunham could use the Alvis’s power to catch him on the straight. Dunham would pass and then the Riley would be glued to the rear of the Alvis. On the 11th lap, Grace’s Riley got back ahead of the Luton driver’s Grey Lady. Moss won the 17-lap race with the Riley a minute behind and the Alvis on his tail for 3rd. This race did nothing but good for the unlikely-looking Grey Lady’s reputation as a racer. Dunham would become a regular in this car around Britain for the next few years.

The Grey Lady Returns

Ivan Dutton and his son Tim have been leading Bugatti dealers and restorers for many years. A few years ago Ivan had been asked to bring a Bugatti to be displayed at a local village fete, which he did. At this event he encountered a woman who appeared towing a Grey Lady behind her Range Rover. The Alvis had been in the family since 1964, but her husband had died and she was loath to part with it. As Dutton had just been contemplating finding a car for Julius Thurgood’s new Top Hat Historic saloon series, he handed over $1,500, but soon realized that he was about to restore what was essentially a 1930s car rather than something more modern. The Grey Lady’s evolution from the TC21, and further back the prewar 12/70, meant this was not a more modern monocoque but a separate chassis and wooden floors. Thus the mounting locations for the body were all in wood. As the car was going to be a serious racer, it would need a rollcage and as Dutton says “you can’t bolt a rollcage to wood…especially if it’s all rotten.”

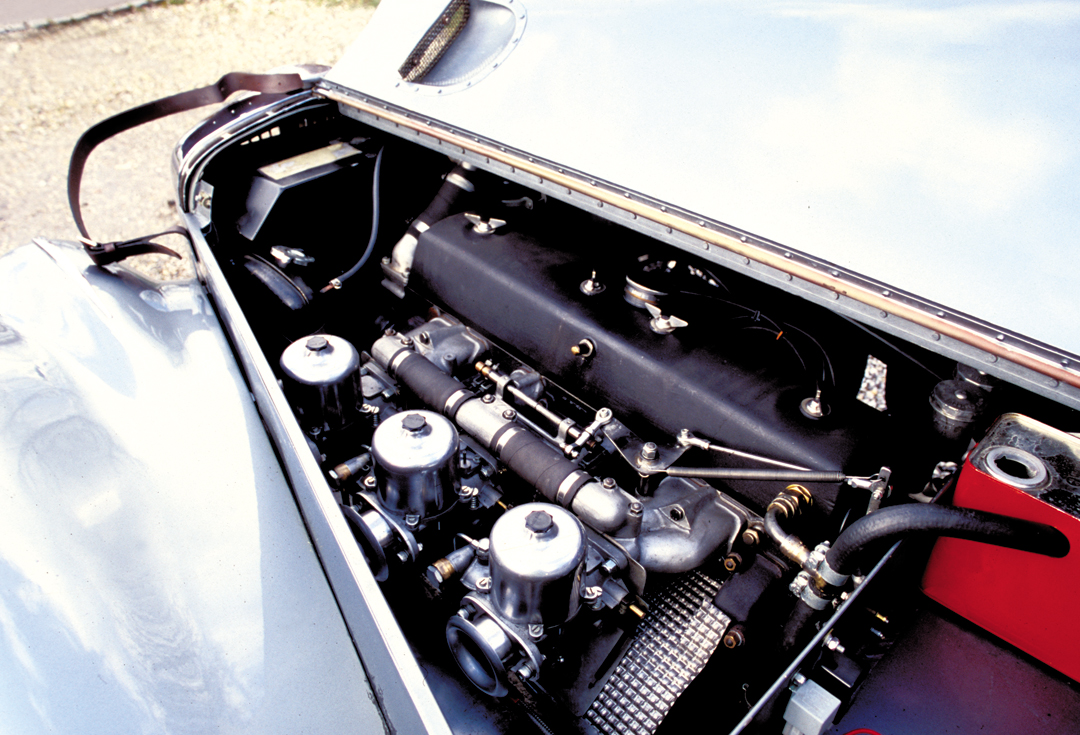

The key to the Alvis Grey Lady’s success in period was its reasonable power output and resultant good performance. Reliability was always an issue with the production cars that raced, so considerable effort went into resolving this. Dutton found that the basically prewar crankshaft design had weaknesses, with “holes in it by the ends and mains and copper pipes where the holes are.” Dave Woods took on the task of designing a new crank which retained the existing larger holes and added bearing holes, rather like the Cosworth DFV. This was an expensive operation at some $7,000, but easily-available Zetec-forged pistons were used, which are just a millimeter larger than the originals. The block was overbored to give 3,065-cc with an increase in compression to 10:1. This was accomplished by using a later head from the TD21 model. With triple two-inch SU carbs and a standard exhaust with a straight through pipe, the power is now around 185 bhp. The cast-iron and heavy radiator was remade in aluminum, and more complex mods were made to allow a switch to dry sump lubrication. The gearbox was remade to something much along the lines of the Ford Capri’s close-ratio box.

In order to meet Goodwood’s requirements that the car look original in appearance, the wooden dash and door trim is retained along with the early bumpers, though they are much lighter now. The car sits on seven-inch-width wire wheels, which are the original 15″ in diameter. They are offset, as in 1954, but all the width is within the arches and the 1953-54 shape is thus retained.

Driving the Grey Lady

I had witnessed the Alvis’s magnificent performance at the Goodwood Revival and like many others wondered how such a “stodgy” looker could go so quickly. Well, we now know a lot of work has gone into all aspects of the Grey Lady’s restoration and transformation into a more modern racer. This meant a great deal of ingenuity went into it as Dutton was keen to stay as original as practical. His description of finding a way to adjust castor in the front suspension is evidence of his approach: “We wanted to keep the standard suspension, so we cut the front of the chassis on each side and just tilted it up before re-welding so it had two and a half degrees of castor. On all the other cars of this era, like the Jaguars, you can move and alter the castor, but you can’t do that with what is really a 1930s car.”

With Ivan’s blessing, it was straight out onto the fast-flowing Goodwood circuit to see just what the “Old Lady” was like. I was impressed. Not only was it immediately possible to drive it quickly, but the handling and braking were superb… yet the feeling of a ’50s saloon was not lost. This is clearly a big car with significant weight, in spite of many changes. After a few laps to get everything bedded in, I was told that 6,500 rpm was the limit, though the engine would not do much beyond 6,000. This was quite accurate and even 5,500 was enough to get a very quick lap under one’s belt. The 4-speed gearbox was ever so flexible and gave no problems whatsoever. In fact, with a short throw it was simplicity itself. Peak revs could virtually be achieved in third gear, though I opted to go easy and went for fourth at about 5,000. The revs rise quickly and between 3,500 to 4,000 rpm, the power comes on strongly. Keeping the triple carbs in tune is something of a challenge but once a rhythm is established, it gets easier and easier to keep the rev counter needle at the productive end and concentrate on sliding the big machine through Goodwood’s slower and medium speed corners. I think it took four, possibly five, laps to take Madgwick Corner flat, with all that mass straining toward the outside of the track. But the handling is inspiring, and with little roll, the Grey Lady can be kept neatly to the fast line through the corner.

The beautiful Alvis interior of the period has been neatly recreated to reinforce the sense of the 1950s and the habitat of people like Gerry Dunham. The cockpit is very spacious…well it had to be for the late Mr. Marshall’s considerable bulk. The Corbeau seat is comfortable and everything is easy to get at. New pedals have been relocated and there is a tidy aluminum sheet floor-pan. All of this makes the task of driving and getting focused on speed a lot easier. Once it was clear that the handling was up to the power increase, and that the brakes were superefficient, I had a chance to push closer to the car’s limit, especially at the high-speed Madgwick and tricky St. Mary’s Corner, as well as the twisty entry to the Lavant Straight. In fact, the brakes didn’t seem to need much attention at all, and that is definitely not 1950s! The secret of Goodwood’s chicane is to carry as much speed as possible into the very tight little complex, use hardly any braking and keep the revs up. The Grey Lady is superb at providing plenty of feel at the back. The tail slides on the exit but is fully under the driver’s management, and revs are maintained to make good use of top-end power up the pit straight.

The totally forgiving nature and predictability of the Grey Lady makes it a real pleasure to drive fast, even at a daunting circuit such as Goodwood. All that torque and power is just the thing to make this a serious driving experience…wonderful 1950s nostalgia with a few mod cons!

Buying and Owning a Grey Lady

There are a number of these lovely cars still in existence, mainly in Britain, though whether you would want to take on the type of project Ivan Dutton committed himself to, I am not certain. This car was not only a restoration of a well-worn road car, it was the construction of a first-class racecar. With Dutton’s knowledge and resources behind you, you might try such an ambitious project but there would be easier cars to do it with, and most enthusiasts for 3-liter cars will go for the better-known Jaguars. That’s what makes this Grey Lady so special. They were rare as racecars and they are even rarer now. With a value of some $50,000 to 60,000, it’s not a cheap saloon racer but it is certainly a good one.

Specifications

Suspension: Front: independent via wishbones/coil springs with optional roll bar; Rear: Solid axle with semi-elliptic springs and Panhard rod. Telescopic dampers front and rear.

Engine: Straight six cylinder

Capacity: 3,065-cc

Valves: Two overhead valves per cylinder

Carburetion: Triple SU HD8 carburetors

Power: 185 bhp @ 5,000 rpm

Torque: 190 lb. per foot @ 4,500 rpm

Transmission: Four-speed gearbox with limited slip differential

Brakes: Front: solid disks; Rear: drums

Top speed: 120 mph

Resources

Sincere thanks to the ever helpful Ivan Dutton.

Alvis Owners Club

Autosport, May 15, 1953

Georgano, G.N. (Editor). The Encyclopedia of Motor Sport. Ebury Press, 1971