The name of Noel Macklin is writ large in the history of British sporting cars. Marques such as Eric-Campbell, Silver Hawk, Invicta, Railton and Fairmile all owe their very existence to Macklin. Back in the March 2013 issue of Vintage Roadcar we looked closely at a very delectable 1929 Invicta 4.5 Liter—a marque that could hold its head high against the likes of Bentley and would go on to win the 1931 Monte Carlo Rallye with a young Donald Healey at the wheel.

The first Invicta went on sale in 1925, fitted with a three-liter Meadows engine but it wasn’t long before this was increased to 4.5 liters. In this guise, the Invicta was exactly what Macklin was looking for as it not only provided the excellent roadholding and handling so desired in Europe, but also provided the power of the many American cars that he so admired. Macklin repeatedly stressed, during the early days of Invicta, that it should have the build quality of Rolls-Royce and performance equal to any Bentley.

Photo: Vince Johnson

Unfortunately, Invicta, like so many marques, was a victim of the Great Depression. While Macklin reacted to the economic times by introducing a smaller 1.5-liter version and lowered prices all through the line, it was not enough. The last Invicta left the factory in October 1933, but as will be seen, Macklin was a shrewd operator as he had managed to sell the company earlier in that same year.

Hudson

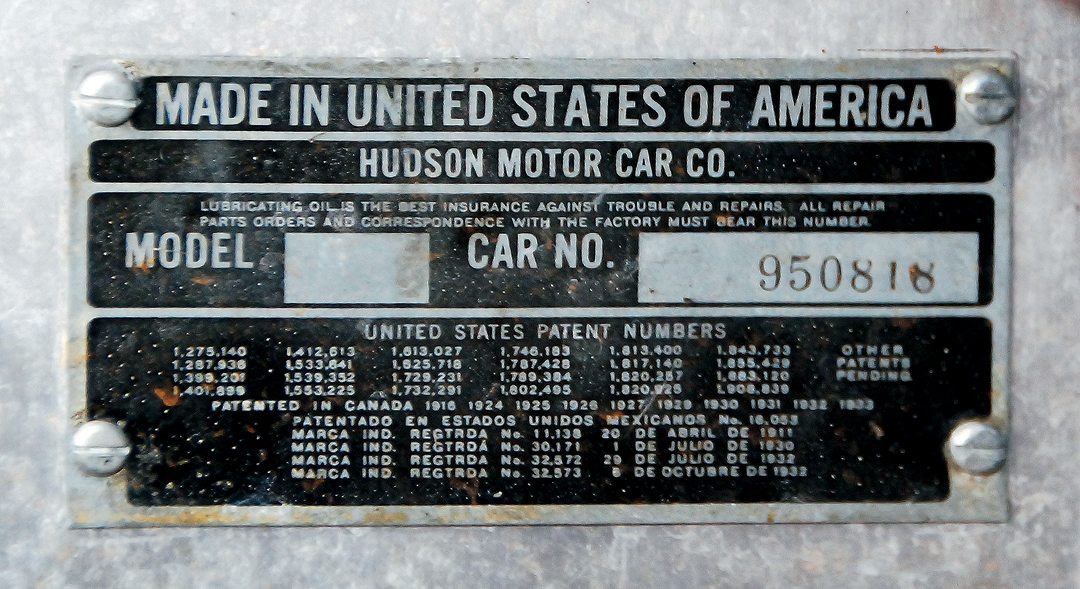

The Hudson Motor Car Company was formed in 1909 with the initial idea to market a car at a set price less than $1,000. The name itself came from Joseph L. Hudson, who founded the Hudson department stores. While not directly involved with the automotive company, he did provide his name, as well as the all-important capital. Just one year after its formation, the production of the Hudson Motor Car Company was 17th among all U.S. motor vehicle manufacturers.

In 1919, the Essex Motor Company was formed, wholly owned by Hudson. Like the Hudson, the Essex was designed to be moderately priced, and within 10 years was the third highest seller behind Ford and Chevrolet. Essex cars were also popular in motorsport, with examples used in hillclimbs and endurance events. In Australia, the marque was likewise popular for inter-city events especially in the hands of Norman “Wizard” Smith who would later seek to break the world land speed record in a car built from a Cadillac chassis and a Rolls-Royce aero engine.

However, due to the Great Depression, the life of the Essex marque was destined to be short. While 1932 brought the introduction of the Essex-Terraplane, just two years later the name was dropped completely. The name Terraplane was derived to capture the public’s fascination with airplanes. Using aviatrix Amelia Earhart in the launch was a sure sign of the connection between the new marque and the airplane.

The Terraplane was intended to be an inexpensive marque and, by U.S. standards, quite small in size with a wheelbase of 106 inches, yet it was fitted with a powerful 3.2-liter, six-cylinder engine.

New models were introduced in 1933, being slightly longer in the wheelbase and powered by an even more powerful four-liter, side-valve, straight-eight engine. The model was thought to provide the greatest power-to-weight ratio of any car being produced, anywhere in the world, at that time.

While the Terraplane car remained in production through to 1937, the following year brought the introduction of the Hudson-Terraplane and, at the same time, a new model Hudson was released that was virtually the same, but carried different badging. There was some talk that there was quite a degree of inter-marque rivalry between Hudson and Terraplane, resulting in the latter ceasing to exist at the end of 1938. Because of their popularity, however, Hudson, Essex and Terraplane vehicles were also assembled/manufactured in the UK, Australia and South Africa. During the 1920s and ’30s, more than a 1,000 Hudson cars were being sold annually in the UK.

Photo: Vince Johnson

Hudson itself merged with Nash-Kelvinator in 1954 to become American Motors, and the last Hudson-badged car was built in June 1957. American Motors, or AMC, was eventually absorbed by Chrysler in 1987.

Reid Railton

During the early 1930s, a man called Reid Railton had become virtually a household name in the UK, especially among those with the slightest interest in automobiles, motoring and motorsport.

Armed with a science degree, Railton commenced employment in 1915 as an assistant designer with truck manufacturer Leyland Motors. There he met John G. Parry-Thomas who would influence him greatly. While there, both Parry-Thomas and Railton designed the Leyland Eight car.

Railton left Leyland in 1923 and, along with Parry-Thomas, set up their own business to manufacture the highly advanced Arab car. Parry-Thomas went on to break the land speed record, but in 1927 was killed while trying to improve on it. Following Parry-Thomas’ death, Railton became disenchanted with the Arab car and, after just 10 had been built, the business was closed and he became technical director and chief designer for Thomson and Taylor at Brooklands.

Famed for their motor-racing engineering and car-building, Thomson and Taylor, under Railton’s responsibility, constructed John Cobb’s Napier Railton car, that would go on to capture the outer circuit record in 1933, and also the Bluebird land speed record cars and boats of Sir Malcolm Campbell. Railton also designed the ERA racing cars that were built between 1933 and ’34.

Photo: Vince Johnson

It was Railton who introduced Cobb to the Bonneville Salt Flats, and who would accompany him for record attempts. During one visit, in 1939, Railton stayed in the U.S. and accepted a position with engine manufacturer Hall-Scott Motor Company and spent the war years on defense projects. Following hostilities, he left Hall-Scott to work as a consultant to Cobb and others.

Railton went on to work as a consultant to Hudson and remained in the U.S. until his death in 1977, at the age of 82.

British

While it may have seemed that the British motoring industry was a large one, it’s clear that there were strong connections between the major players. Information is scant as to just how the Railton motor car came about, but there is no doubt it was through friendships and acquaintances.

It’s known that Noel Macklin and Reid Railton were friends, and the latter would have been fully aware that Invicta sales were dropping due to the difficulties experienced during the Great Depression. What is not known is the influence that Railton had on Macklin to sell the company in 1933.

Both were greatly impressed with the more powerful American cars that were available on the UK market, and during the early ’30s Railton started to develop contacts within the U.S. automotive industry. In 1932, Railton was loaned a straight-eight Essex-Terraplane and was highly impressed by its effortless performance and expressed his opinion to Macklin. Not long after, Macklin bought a Terraplane 8 and gave it to his sister-in-law, Violette Cordery, who ran it as part of the Terraplane team in the 1933 Scottish Rally where they won the team prize.

Macklin had his fingers burned toward the end of Invicta production as after all, apart from the drivetrain, it was assembled in the factory of the Fairmile Engineering Company located in the garden of his private home in Kent. Very little was actually made in house, as all the components were sourced from outside suppliers. An expensive exercise.

Potential

Clearly Railton could see the potential with the Essex-Terraplane, and he would have expounded on its value to Macklin who was looking to recover earlier losses. The idea was formed to obtain a supply of Essex-Terraplanes from Hudson, rejig the suspension and refit them with a suitable English-style body.

Being as astute as he was, Macklin saw the simplicity of the idea in comparison with the multiple and expensive steps in the production of the Invicta. Macklin could also see the marketing potential in lending Reid Railton’s name to the whole project.

It is at this juncture that the arrangement becomes confusing, as many contemporary motoring writers stated that the new Railton motor car was based on a redesign of the chassis by Reid Railton along with many other aspects. As mentioned, Macklin was astute and the misnomer was in many ways down to him, as during the early days of the marque he said nothing to discount the involvement of Reid Railton. Of course, he had good reason to do so, because the average motorist would have been well aware of the Railton name.

Over time the truth came out. The extent of Railton input was that the radiator/grille would be more streamlined (and Invicta looking) and the chassis would be fitted with a full set of hydraulically controlled Andre Telecontrol friction dampers. Of course, the use of the Railton name was of prime importance and for this he received a royalty payment of £6.10 for each vehicle.

Once operational, Railton production was straightforward, with chassis being sent from Hudson in Canada, to Hudson in the UK, as a right-hand-drive CKD kit. Assembly would be undertaken by Hudson (UK) and driven in batches to the Railton plant. At the Railton plant, the Hudson radiators were replaced by the Railton units and the damper sets fitted. Once completed the rolling chassis were then shipped to various coachbuilders for the fitting of a lightweight body, and the Hudson radiators returned to Hudson (UK) to be used in the next batch.

Macklin would have been delighted with the arrangement as it has been said that apart from the cost of buying the rolling chassis from Hudson he spent only an additional £12 on each car before it was despatched to have its body fitted.

Railton production continued until the outbreak of WWII in 1939, and while the majority were powered by the straight-eight, a couple were fitted with a six-cylinder to incur a lesser government tax. In 1938, a smaller Railton was produced based on a Standard chassis and powered by a 1,267-cc, four-cylinder engine.

While a handful of Railtons were made after WWII, the marque really didn’t survive into the post-war era. During the war, Macklin devoted himself to the construction of gunboats and torpedo boats. Afterward, he was appointed to oversee the disposal of surplus small boats and was knighted for his contribution to the British war effort. Sadly, he died not long after, in 1946.

In total, 1,460 Railtons were built, most fitted with complete bodies, but some were sold overseas as rolling chassis to receive local bodywork. Prior to the outbreak of WWII, Macklin sold the Railton business to the Hudson Motor Car Company.

As an aside, the Terraplane chassis and engine was also used by George Brough who, with his father, had been building Brough Superior motorcycles since the end of WWI. It is thought that around 80 Brough Superior cars were produced with either eight- or six-cylinder engines, the latter fitted with supercharging.

South African GP

It was news in the motoring press of the day. A race titled “The Border 100” was scheduled for December 27, 1934, and was to be the first serious attempt to hold a road race in South Africa. The location was the Marine Drive Circuit that was constructed as a scenic road on the west bank of the Buffalo River, at East London, on South Africa’s east coast. It was an event that has since become known as the inaugural South African Grand Prix.

The race was to be six laps of the 16-mile Marine Drive Circuit, with a total prize money of 430 guineas (a guinea was equal to one pound and one shilling) plus the Barnes Trophy—said to be worth a further 100 guineas—going to the winner.

Reid Railton was very friendly with wealthy American-born racing driver Whitney Straight, and the former was heavily involved with the Straights’ team of Maseratis. It may be conjecture that Straight was approached to compete actively in a Railton, but he was coming to the end of his racing career so he declined. This doesn’t mean that he wasn’t impressed with the car, as he spoke positively about the Railton to his younger brother Michael who did buy one that was fitted with a Sports Tourer body by Berkeley.

However, he had heard of the Border 100, and the thought of racing in South Africa certainly appealed. So, when he was invited, he formed a team that included Dick Seaman with his MG K3 Magnette, him in his own Maserati 8CM and he convinced brother Michael to run the event as well in his newly acquired Railton.

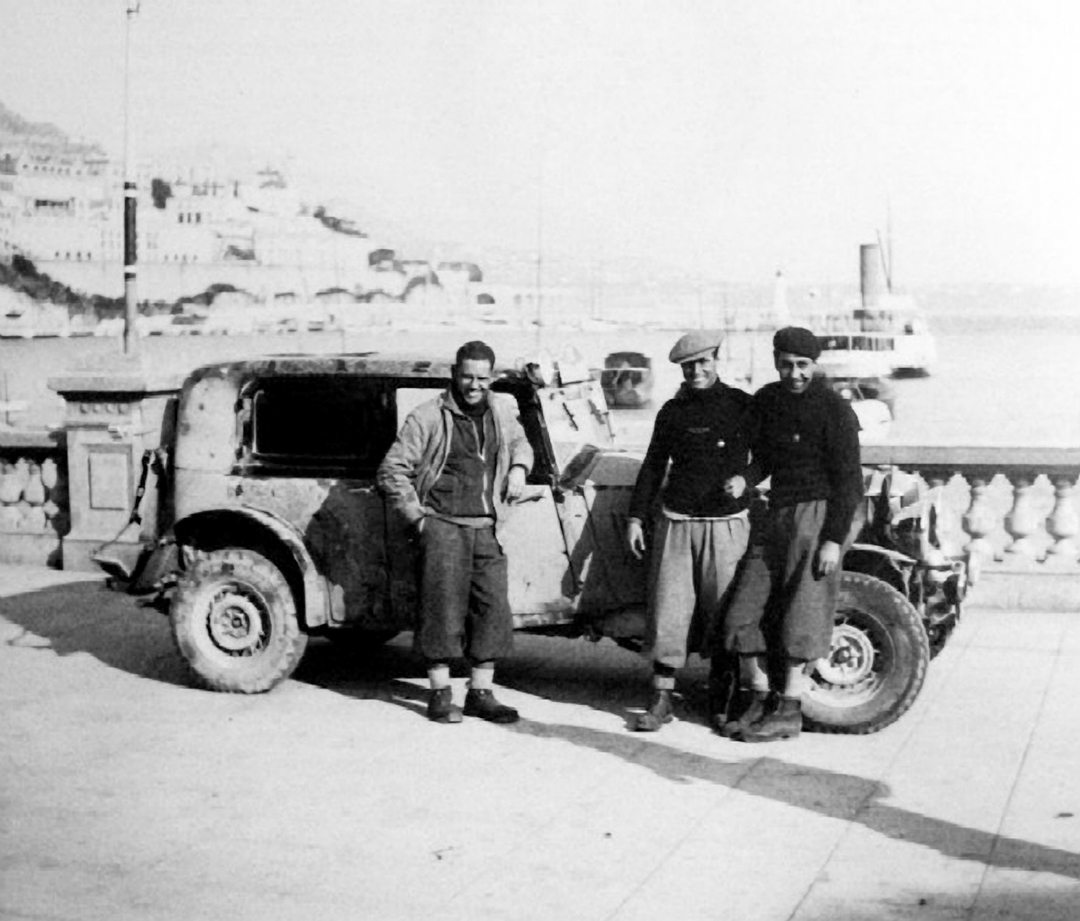

Whitney Straight then offered well known Italian automotive engineer Giulio Ramponi the role of manager, chief mechanic and tester for this newly formed team. It was agreed that the cars would be sent by ship, along with Ramponi, while the Straight brothers and Seaman would fly, as Whitney was a highly skilled pilot.

At the time, Whitney Straight was 22 years of age, Dick Seaman was 21 and Michael Straight was just 18. They hired a brand-new de Havilland Dragon Rapide that had a top speed of around 100 mph and perhaps 60 mph into a headwind.

In his 1983 book After Long Silence, Michael Straight said that they flew most of the way at 500 feet. The journey took them all of five days,with the scenery toward the end consisting of such wildlife as hippopotamus clambering out of a Nile River mud hole and stampeding elephant herds. Later, they had lift problems due to the hotter and thinner air around Salisbury (now Harare, Zimbabwe) and sent a herd of gnu scattering due to unexpected take-off problems. They finally arrived, however, at East London and were greeted by large banners saying “WELCOME.”

![The results of Noel Macklin’s ingenuity and influence are embodied in both the Railton-Terraplane (right, pictured with full road gear) and the 1928 Invicta 4.5-Liter, featured in Vintage Roadcar [March 2013].](https://www.supercars.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/RACEpro201603-p10.jpg)

Handicap Race

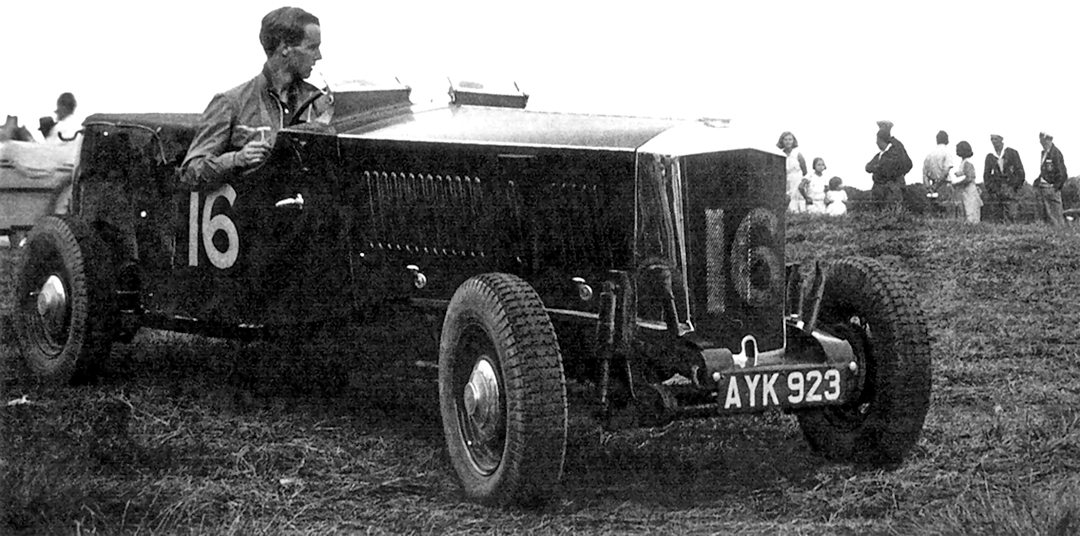

On the day of the race, more than 35,000 spectators lined the circuit. The race itself was a handicap event with the Railton starting in 16th position, the MG in 17th and the Maserati backmarker in 18th.

Ramponi had prepared the three cars, with the Railton stripped of its fenders and any other unnecessary weight. The rest of the field consisted of quite a range of cars including Riley, Austin, MG, Ford V8, Frazer Nash and Terraplane.

Needless to say, Whitney Straight ran through the field and, at an average speed of 95 mph, was first across the line. Seaman was running 2nd but retired with oil problems, leaving a Ford V8 to finish 2nd with the Railton of Michael Straight 3rd. Ramponi was ecstatic and said to Michael Straight that he had a great future as a motor racing driver; however that was not to be as it was his first and last attempt at any form of motor sport.

The next morning the three set off back to England in the Dragon, eventually arriving much to the relief of Whitney and Michael’s mother!

Whitney Straight would go on to be a much decorated WWII pilot, later managing director of British Overseas Airways Corporation until his death in 1979, at the age of 66. Dick Seaman died during the 1939 Belgian GP, while driving a Mercedes-Benz. He was just 26 years of age.

Michael Straight went on to university at Cambridge, studying economics, where he became part of the student communist movement. He could see the problems forming in Europe caused by Adolf Hitler, and he thought that being involved with the movement was a way of resisting Hitler. However, he found himself under close scrutiny by secret agents of Soviet intelligence, especially as some of his friends—such as Anthony Blunt—would later form the most daring Soviet spy ring of the post-war period.

Disillusioned, he returned to the U.S., and while keeping secret his earlier involvement with the communist party became a speechwriter and adviser to President Roosevelt. He served in the U.S. Army Air Force and later, after being a target of Senator Joe McCarthy’s anti-Communist campaign, went to the FBI with his story. As a result, the spy ring headed by Blunt was unmasked, causing a huge furor in the British House of Commons. Michael Straight died January 2004, in Chicago, aged 87.

In Australia

So how does the Railton driven by Michael Straight in the inaugural South African Grand Prix find its way to Australia?

I first heard about Jim Scammell a few years back, when he was organizing the Collingrove Vintage Speed Hillclimb, held every October at Angaston in the Barossa Valley, in South Australia. Organized by the Sporting Car Club of South Australia, the event is restricted to pre-1941 vehicles. If you have a newer car you have to be really nice to the organizers and you might receive an invitation.

Jim was running a 1934 Railton and as I hadn’t long beforehand finished the Vintage Roadcar article on the Invicta, I was interested.

Much earlier in his life, Jim spent a considerable amount of his time pouring over various sports car and hot rod magazines, as well as joining with friends in attending vintage car events. Eventually, Jim’s father took note of his son’s interest and they went looking for a car. Just $30 later an Amilcar was part of the family, but it was discovered to have a cracked cylinder block. That was replaced by a 1927 Chevrolet Capital Fisher-bodied coach and again after $30 that was brought home. At the age of 14, Jim then spent every weekend of the following year restoring the car while using his father’s money. Once Jim turned 16, he got his driver’s license and it was used as an everyday car. It still takes pride of place in his garage.

“By that stage restoration was in my blood,” Jim said. “I was still at school and couldn’t spend every weekend chasing sheilas, so I started looking for another car. That turned out to be a 1924 Essex Four sedan that was quite rare in Australia. Then I saw a photo of Wizard Smith breaking records in his Essex, and from then I was fully focussed on building one just like it. Not long after, I mentioned it to some blokes at the Sporting Car Club and one said that he knew where the original engine was. Anyway after tracking down a shed full of vintage stuff I paid a visit and was just amazed about the amount of stuff in it.

“Right down the back was this racing Essex engine and I asked the old bloke who owned it if he would sell it to me. I was just 17 and had my very first checkbook in my back pocket, having never written a check before in my life. I offered him $120, and he couldn’t move fast enough to get the engine out for me. That was in 1967, and it took me until 1994 to finish that car because life gets in the way sometimes. I’ve still got that, too!

“Then there was a Jaguar MkIV,” Jim added. “A few years back I started building a replica of the 1923 Pikes Peak Essex Four, and was doing well until the Railton came along.

Previous Owner

“It was Ray Pank who brought the car in from the UK,” Jim continued. “Ray is in his 100th year, and has been a car nut for most of his life, especially Hudson and Essex. Ray bought the Railton in 1982, in the UK, and brought it out to Australia. It just happened to be the ex-Straight Railton.

“Since then, he did quite a bit of work on the car especially to do with engine cooling that he was quite obsessed about. The good thing is that he kept all the original stuff that I will refit over time.

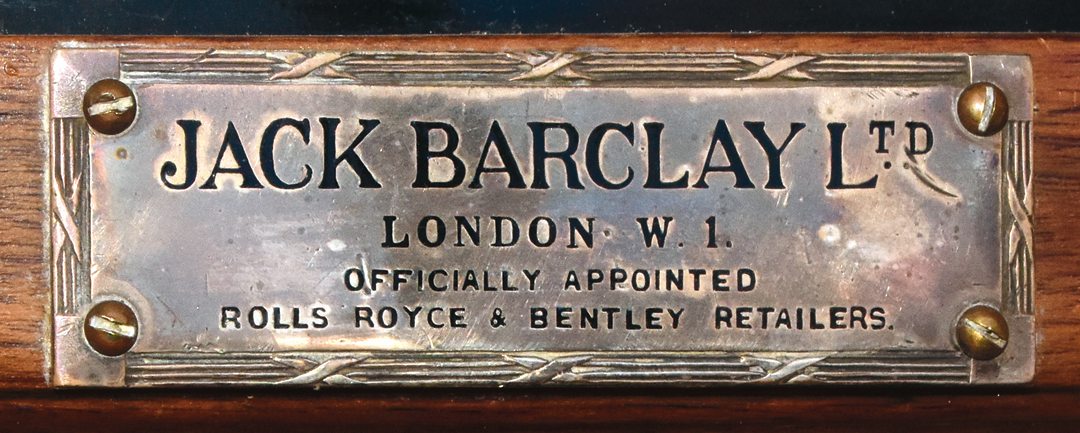

“I knew Ray had the Railton, but I didn’t know all that much about its history. I bought it from him in November 2014, but throughout the year prior I did some research for him on the Internet and found the one and only photo there is of Michael Straight sitting in the car at the 1934 South African Grand Prix. At that stage, I had no idea that the car would eventually be mine. Plus, I didn’t know that he was divesting himself of quite a bit of his collection. I did find out that he had been giving stuff to the Birdwood Mill Museum, including a 1922 Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost, along with a Bentley that used to belong to Mike Hailwood’s father. He was getting tax credits for each car, as donations to the museum are tax deductible.”

“What I didn’t know was that Ray was negotiating with the Museum on the Railton, and they wanted to see some evidence that it was the Straight car. Of course, the photo I found was exactly what he was looking for as it showed the English registration number. When I found out that he was giving it to the museum I went straight home and wrote him an impassioned letter saying that I wanted to buy it. I dropped the letter into his letterbox in the middle of the night and called the next day. That’s when the negotiations between us started and I ended up buying it.

Exploits

“I like the South African GP story,” Jim added. “Despite it being Michael Straight’s very first race, he must have been a mean steerer. In the book that he wrote later about his spy exploits, he did include something on the race. He said that Giulio Ramponi rushed up to him after the race and kissed him saying that he was a fantastic race driver. Ramponi put the car back together when it was back in England and Straight kept it for a few more years.

“He mentions it in the book, and that he was on the French/Spanish border when the Spanish Civil War broke out. As far as I know, when he came back he sold the car, but between him and Ray there have been only three or four owners. Ray had been trying to buy a Railton for a couple of years. He had joined the Railton club and thought that he could find one through the magazine. What happened, however, was that by the time the magazine had traveled from England to Australia, any cars for sale were sold. So Ray made contact with the editor and asked him to ring him when one came up for sale. It just happened that the Straight car came up next and Ray ended up buying it over the phone in 1982 and then picked it up the next time he was there.

“While Ray had the car, I had never seen it on the road,” Jim noted. “Since I bought it, I have always been keen on it being seen, and one way is through competition events like Collingrove Hillclimb. It was the provenance of the car that I wanted to get out in the open, such as that amazing trip to South Africa by those three young lads in the Dragon Rapide, which then was a state-of-the-art passenger airliner.

“Not long back I took the Railton across to Victoria by train to spectate at the Rob Roy Hillclimb, and while there have a new set of tires fitted to the car. I think I had driven it around 20 miles beforehand and I thought the tires that were on it were as old as Ray. So I had new tires fitted and headed to Roger Rayson’s home where the Invicta was that was in Vintage Roadcar a couple of years back. It was interesting to put them next to each other and compare. Fitted with new tires, I drove the car home with a mate along the Great Ocean Road. A wonderful trip!

“I want to leave the car stripped like it is for the next couple of years so it gets known. I’m pleased to say that my son is starting to get interested, and he ran it at Collingrove and was quicker than me. He just loved it! So, I am looking to add a Hudson Railton special to my collection for further competition work.”

Straight-Through

In this politically correct day and age, the opportunity to drive a car on the road with a straight-through exhaust pipe doesn’t happen very often. What a wonderful booming sound Jim Scammell’s Railton makes, and it’s there right through the rev range. When Jim told me about his early days of avidly reading hot rod magazines it all just made sense. With its fenders removed and open exhaust, it’s a mid-’30s hot rod—and just wonderful.

Thankfully, I wasn’t driving as we slowly motored past a member of the local police Highway Patrol, our hearts fluttering.

The car itself was surprisingly comfortable—nothing out of the ordinary—with its steering (heavy), normal pedals and center, three-speed shift. Not too sure about the modern tachometer, but Jim assured me that the original instrument was soon to be refitted. The lack of synchromesh on any of the gears just wasn’t a problem, as the gears just seemed to slip into place without any crunching at all.

Acceleration was what I would call brisk—in fact more than brisk. The car must have been a sensation in the 1930s. As mentioned, the gear change was smoother than I expected and once into third, or top, the car just kept on accelerating. Sure pleased that the Highway Patrolman wasn’t nearby! The brakes? Well, I knew they were there and proton pills were certainly needed, even with the mechanical drums being changed over to hydraulic.

Being a road-registered car, we were not restricted to just a few laps around a circuit, so we headed off to the Fleurieu Peninsula, south of Adelaide, which Jim assured me was akin to the landscape around South Africa’s New London—barren, brown vegetation, the ocean and lots of sand! Fifty miles later, the smiles had not left our faces as the car boomed along.

What was amazing about the Railton was the torque of the straight-eight engine. The Railton is a true top gear car that allows you to stay in top gear for the slowest corner or intersection, but if booming acceleration brings on the smiles, it’s down a gear and hard on the accelerator.

Truly a most enjoyable car, and perfect for vintage competition. History tells us that the Railton is now seen as the first of the “Anglo-American Sports Bastards,” which was followed by such cars as the Brough Superior, Jensen, Allard and the AC Cobra. Certainly, all in good company!

Thanks to Jim Scammell for allowing us to enjoy his 1934 Railton-Terraplane.

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis: 1934 Hudson-Terraplane pressed steel cruciform frame.

Body: Timber-framed, aluminum-paneled body; Berkeley Coachwork by Motor Bodies & Engineering Co., Ltd.

Wheelbase: 116 inches (2,946 millimeters).

Track: 56 inches Front & Rear (1,422 millimeters).

Weight: 2,227 pounds (1,010 kilograms) (stripped for racing).

Suspension: Front: I-Beam Elliott-type drop-forged carbon steel axle with semi-elliptic springs and telescopic shock absorbers. Rear: semi-floating axle (ratio 4.11:1), with semi-elliptic springs and telescopic shock absorbers.

Steering Gear: Gemmer worm and sector type; Ratio 15:1.

Engine: Straight 8-cylinder 254 cubic inches (4,168 cc).

Power: 121 hp @ 3,000 rpm.

Carburettor: Carter Downdraft 1¼ inches

Clutch: Single-disc, cork insert type (108x), operating in oil.

Gearbox: Unit type with helical gears.

Gears: 3 forward, 1 reverse.

Foot Brake: Bendix mechanical type, single anchor drums (modified to hydraulic, will return to cable actuated).

Hand Brake: Gearbox-mounted.

Wheels: Drop Base 16×4.00, four-bolt wire, Front & Rear.

Tires: Coker Excelsior Stahl Sport Radial 600R-16 Front & 650R-16 Rear.

Resources / Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Noel Macklin: From Invicta to Fairmile. by David Thirlby. Published by The History Press. ISDN 0752438794

After Long Silence by Michael Straight. Published by W W Norton & Co Inc. ISDN 039301729X