Inspired by J.G. Parry Thomas and Reid Railton, the Brooklands Riley—the sporty member of the Riley 9 series—was introduced for 1926. Upon its arrival, this great little car became “the” competition car for the Riley marque, and during the following years proved successful around the world. The Riley Brooklands was comfortable at the track with which it shared its name, on the roads of France at La Sarthe or, in the case of this car, the roads and tracks of New Zealand. The Riley Brooklands was a hit—a real globetrotter.

RILEY, FROM CYCLES TO CARS….“AS OLD AS THE INDUSTRY”

Photo: Pete Austin

The cycle craze was sweeping Britain at the turn of the century, and many manufacturers of this mode of transport were springing up all over the place—some more successful than others. William Riley who had business interests in the weaving and textile industry purchased the Bonnick Cycle Company in the closing years of the 19th century and under his guiding stewardship the company flourished. On May 23, 1896, the Riley Cycle Company was formed in Kings Street, Coventry, and for the next 40-plus years the Riley name became one of the finest and most respected in motoring.

Riley proved to be an innovative company from the start, developing such innovations as the first constant-mesh gearbox and the first detachable wheels (indeed, over the years their wheels were fitted to many cars including Austro-Daimler, Hispano-Suiza, Mercedes, Napier, Rolls-Royce and others.) Even the record-setting “Blitzen Benz” wore Riley wheels, all from a company that started with cycles and a family that built their first car in 1898.

One early design was the “Royal Riley,” a quadricycle that was exhibited at Crystal Palace in November 1899, at the National Cycle Show. This particular vehicle had a forecarriage in which a passenger rode, and it was powered along by a 2¼-hp engine. That same year, Riley products also entered into competition, and through many versions of powered vehicles the marque would become a force to be reckoned with. This continued all the way through to, and beyond, what many regard as the highlight for Riley on the track when, in 1934, Riley cars finished 2nd, 3rd, 5th, 6th, 12th and 13th at Le Mans!

Photo: Pete Austin

Riley scooped the 1500-cc and 1100-cc classes along the way during that year’s 24-hour classic. The team prize was secured and also the Rudge-Whitworth trophy in a race won by the Alfa Romeo 8C of Luigi Chinetti and Philippe Etancelin. The 2nd-placed Riley 6/12 of Jean Sebilleau and Georges Delaroche may have been some 13 laps back, but this was a triumph for Coventry! Miss Dorothy Champney and Mrs. Kay Petre finished 13th in their Ulster Imp, recording the fastest drive ever by a female team, and after the race, all six Riley cars were then driven back from La Sarthe to Britain under their own power!

With the company, and family-owned associate companies formed early in the 20th century, the manufacture of motoring components expanded alongside the core product of the cycle. In 1903, Percy Riley set up the Riley Engine Company, building a range of three engines with 2¼, 3 and 3½ hp. The latter was available as water or air-cooled, and all featured a patented Riley valve gear, incorporating a single cam and two rockers operating the inlet and exhaust valves, while also providing valve overlap. The 6-hp tricar also used a three-speed constant-mesh gearbox, and very quickly a 9-hp unit followed. This range of engine was a commercial success and victories in events for Victor Riley and Stanley Riley were commonplace.

In 1906, Riley introduced a 9-hp, V-twin four-wheeled car. Using a tubular frame, this vehicle also boasted the ability to have its wire wheels removed. These items became standard fitments. The 12/18-hp variant followed, and this vehicle was triumphant in the Aston Hill Climb of 1908, and continued with class wins in the much-valued Scottish Trial. By 1911, the Riley company had become fully focused on the production of motor cars, and this continued strongly until war broke out in 1914.

The Riley Engine Company greatly aided the war effort, with the manufacture of the tools used for war during the period of terror in Europe, with Riley refusing to profit from the works handed from the British Government at this time. The war also brought some work with aero engines, but after the Armistice, the motorcar returned to the forefront and at Olympia, in 1919, a new model was displayed.

The Eleven was shown to the public at the Motor Show, where Riley also introduced its now famous blue diamond logo. The Eleven was fitted with a side valve, 4-cylinder engine of 10.8-hp. Winning in competition was again possible for Riley, and the Sports Two Seater of 1922 did just that. However, in 1923, the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders banned its members from direct competition, and so cars were passed into the hands of privateers for use. Soon, the range increased and the foundations were laid for the cars that followed in 1926.

Photo: Julian Sutton

A fabric-bodied, four-seat sedan, powered by the famous 9-hp engine was introduced, becoming the first Riley Monaco, and it was joined by the San Remo sedan and a couple of open-top examples. When the cars arrived, racing and speed breaking legend, J.G. Parry-Thomas, quickly sat up to take notice of the engine. Parry-Thomas made a chassis, and with a Riley engine fitted, Reid Railton drove it with much success at Brooklands. As a result, Riley soon put into production a Speed model, which simply became known as the Riley Brooklands Nine.

It was a Riley Brooklands that won the Rudge-Whitworth Cup at Le Mans in 1934, and is detailed in this profile. Throughout the 1930s, Riley gained notable on-track success, much of it courtesy of Freddie Dixon. In 1935, Dixon won the Ulster Tourist Trophy in a 1½-liter car and he was able to repeat a famous double by taking victory again in 1936. Dixon also won the BRDC 500 at Brooklands—an event organized by the British Racing Drivers Club with its roots set back in 1929 when the race was started as a British equivalent to the Indianapolis 500.

Dixon’s speed at Brooklands was a superb 116.86 mph and he only missed out on a “500” double, when he was pipped to the flag the following year by the Bentley-powered Pacey-Hassan Special. Dixon and Riley also took the BRDC Gold Star in 1934 and a Brooklands 130-mph badge in 1935, confirming their place in the history books, and as a result the name of Freddie Dixon will always be displayed on the BRDC Gold Star “Roll of Honour” in the Clubhouse at Silverstone.

Photo: Julian Sutton

As an independent company, Riley continued until 1938 when it finally lost its bid for survival and was sold to Lord Nuffield. Riley (Coventry) Limited was gone, but the name would live on, and the Riley logo would be seen on sedans and family cars right up until the 1960s. The Riley name is now dormant, but owned by BMW—which has successfully rebuilt the Mini brand into a multi-million car operation for the 21st century.

Photo: Julian Sutton

Having just witnessed the Vintage Sports Car Club’s celebrations at Silverstone to mark the 80th anniversary of English Racing Automobiles (ERA), I feel any Riley article must touch on the fact that those superb English “uprights” were powered by a much-modified version of the Riley 6-cylinder engine.

Raymond Mays created ERA after driving the “White Riley,” which was a car fitted with a 6-cylinder engine and a supercharger. This car acted as the development tool for the famous ERA cars that were so successful in period, and are so loved today. A race for ERA cars took place at the VSCC Spring Start, and made for a wonderful sight. For any enthusiast who has been able to enjoy watching an ERA attack a track on “full noise,” however, it is the sound of the Riley-derived engine that sends a shiver down the spine. Riley and ERA—perfect!

Photo: Julian Sutton

C 8075

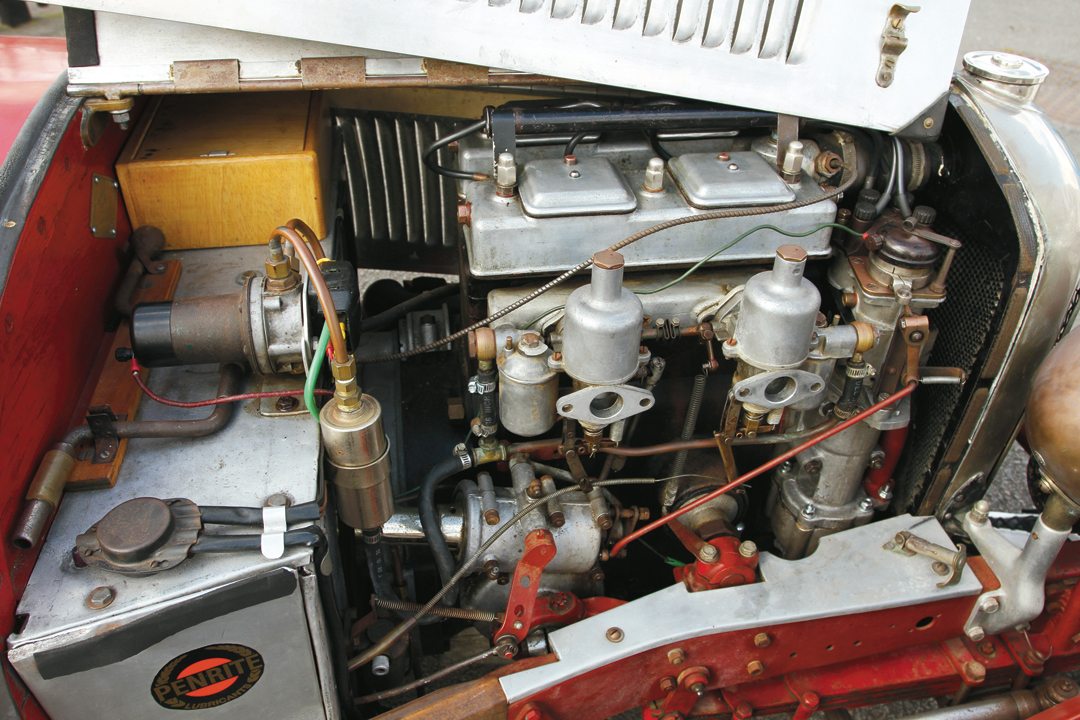

Introduced as the sports model of the Riley 9 series, the low-slung Riley Brooklands was a highly successful car. A major factor in this being the 1087-cc, 32-hp, 4-cylinder engine, with twin high-mounted camshafts controlling the valves through short pushrods. The engine also had hemispherical combustion chambers in the specially designed head that carried the initials of PR after Peter Riley. The modified unit could attain around 50-hp and had a good top speed.

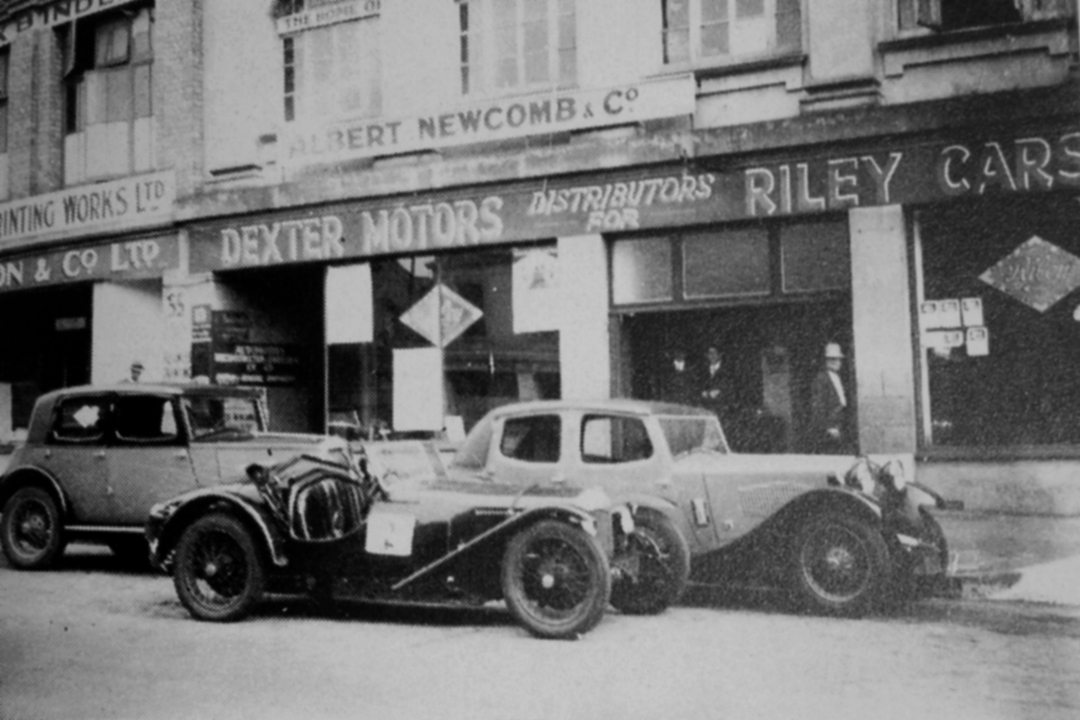

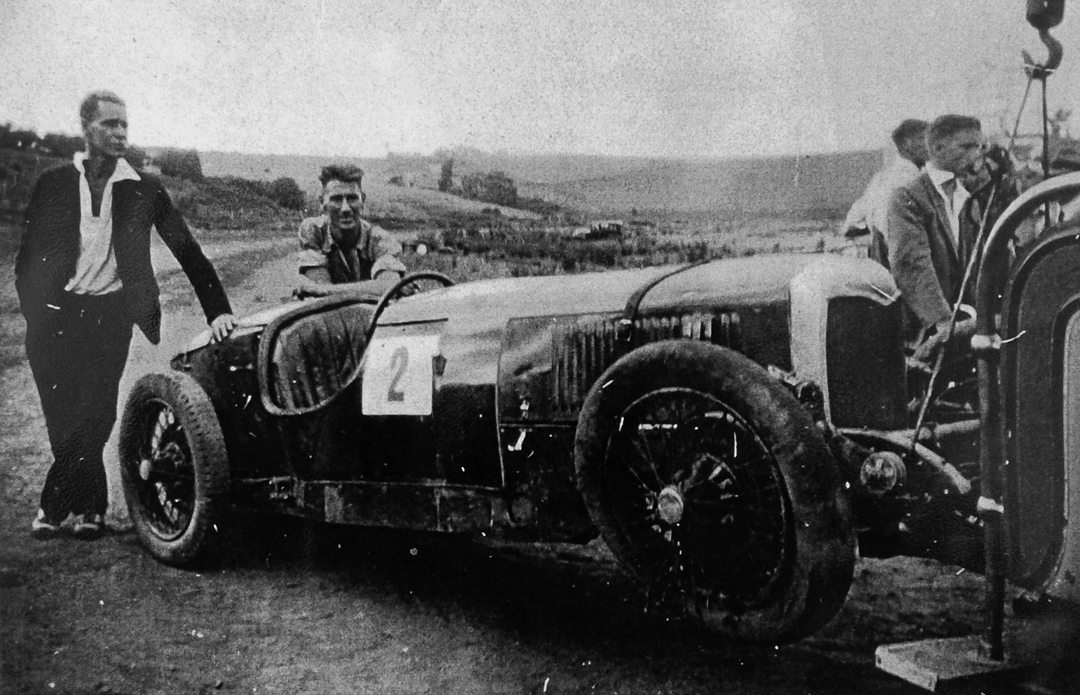

This car (C 8075) was ordered at the London Motor Show and exported to New Zealand as a 1930 model. It was bought through Seabrook Fowls, second hand, and sold to Auckland furniture manufacturer, Harry Butcher.

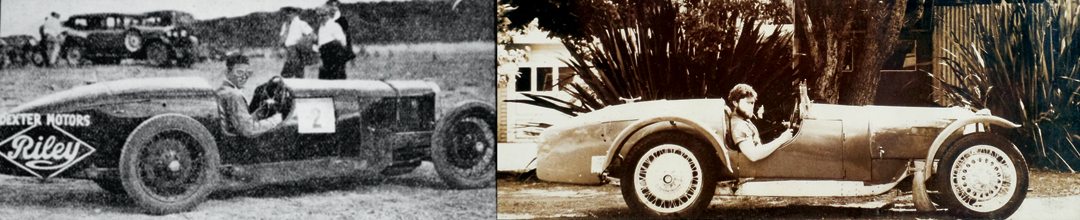

The car first appeared in competition at the Hennings Speedway, near Auckland, where Butcher put Reg Grierson behind the wheel. Grierson scored four 2nd-place finishes and a 4th with the car—quite a successful day!

Photo: Julian Sutton

For the 1931 season, George Smith became the car’s preferred driver, instantly gaining placings at Hennings and again in the New Zealand Beach Handicap at Muriwai. In 1932, Smith again was successful with the Brooklands, taking two wins, a 2nd and a 4th at Muriwai, while also setting FTD at the Bell’s Hill Hillclimb.

After using the car for a couple of seasons, Butcher took the difficult decision to sell it, and it passed to Arthur Dexter late in 1932. Dexter was the son of the Riley distributor in Auckland, Reuben Dexter, and as soon as he took ownership of the car he started to race it. Dexter took victory in the Hennings Championship and Consolation Handicap, although on one occasion he managed to crash the car during a victory lap amid wild celebrations!

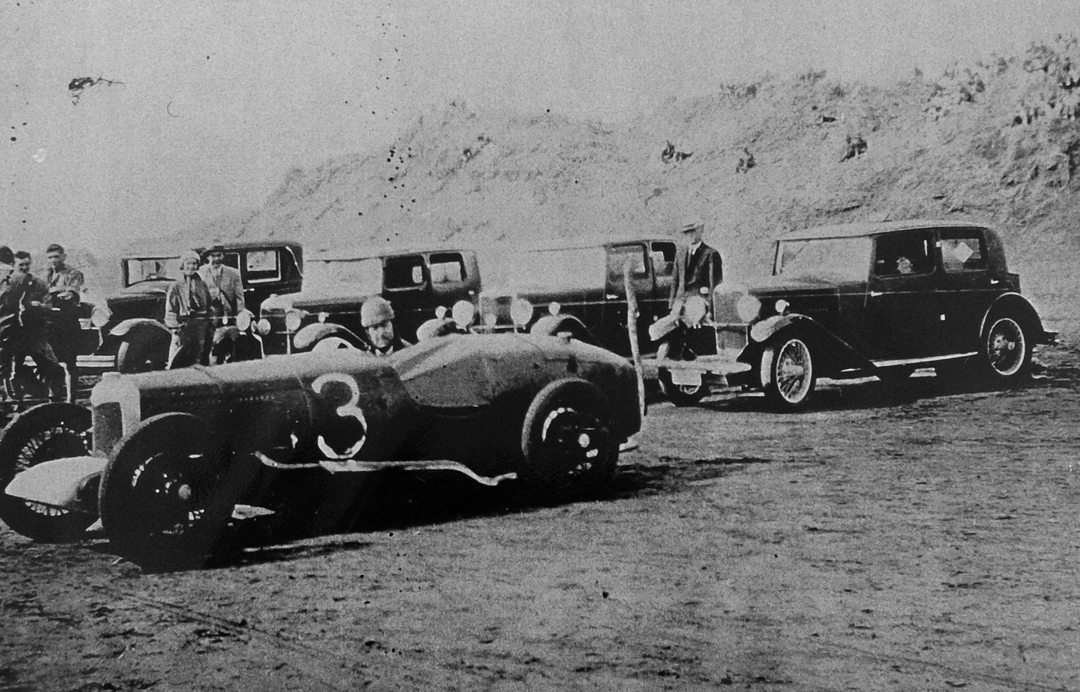

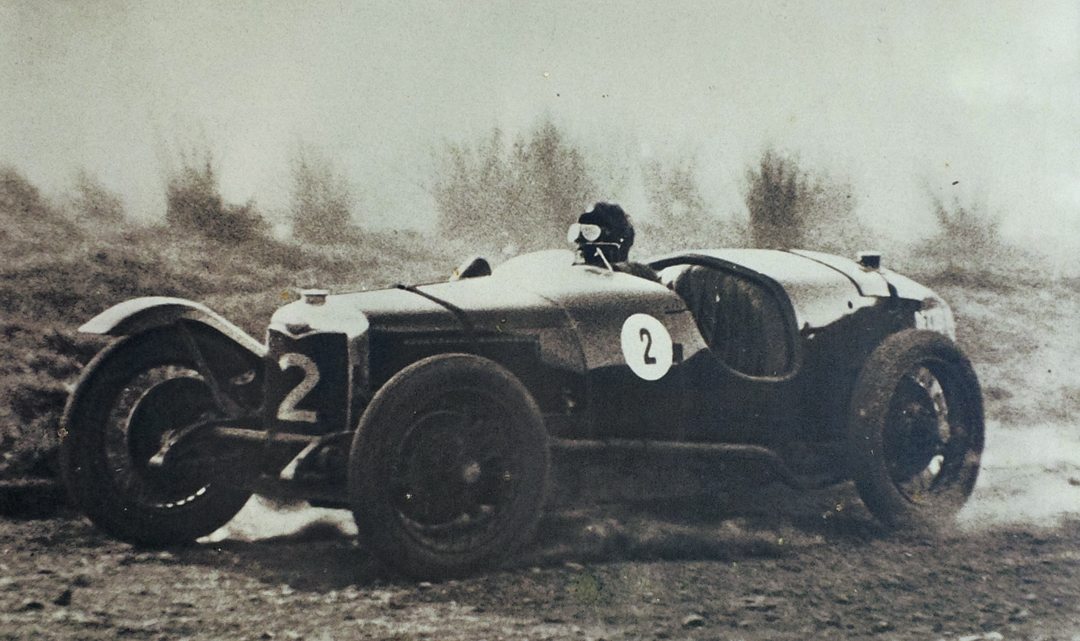

Dexter survived a “big moment” on the gravel roads of Orakei to carry on and win the 1933 Prosperity Grand Prix after quite a battle with Reg Grierson, who was driving an Austin Ulster. In November, after winning at the Auckland track, Dexter blew his engine when the crankshaft snapped, but he repaired it for the February meeting at the 1¼-mile Speedway. Throughout 1934, Dexter had numerous battles with Bill Galpin, who was at the wheel of the “works” Riley. Dexter finished ahead of Galpin on four of nine encounters, although he scored only one victory, which was at Muriwai.

In the final meeting of the season, Dexter took a 2nd and two 3rds before managing to bury the nose of the car into a solid earth bank. Dexter was ejected from the cockpit by the accident, but was unharmed save for a cut and bruise or two, althought when the car returned to competition it appeared as an offset single-seater with modified “hot rod” components.

During 1934, the Brooklands ran in its modified form and, with Dexter driving well, won a heat of the Ebbett Motors event, but was 2nd in the final. Three victories at the Gloucester Park opening were certainly highlights for the car in this guise, as was a 2nd-place finish to Holm Kidston’s Mercedes-Benz in the New Zealand Beach Championship.

Further wins came in 1936, including the coveted Michelin Cup, while Dexter also set a lap record of 40 seconds at the Hennings Speedway. During 1937, the car was converted into a midget racer, using a Brescia Bugatti chassis, but the engine from the Brooklands. Although not all Riley Brooklands, those parts still in competition carried on winning—including the Light Car Cup of 1938.

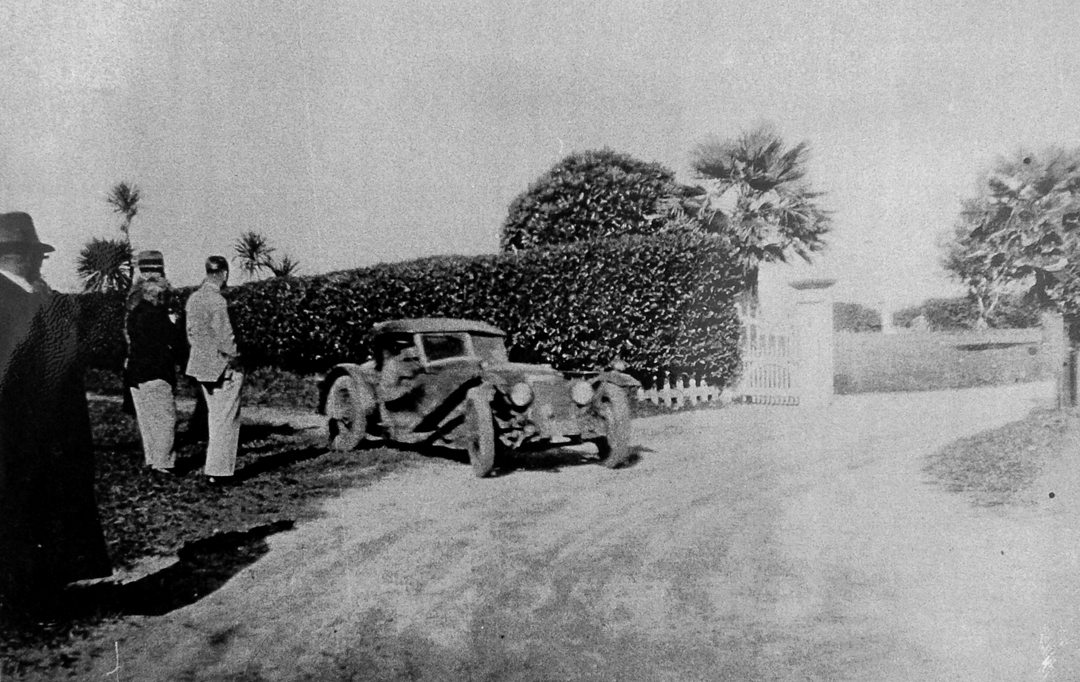

In 1939, Dexter suffered a shooting injury and didn’t compete much, so Bert Raper drove the Brooklands-engined vehicle to victory in the Robinson Trophy and to 2nd in the New Zealand Beach Championship. After the war, the car and its components became slightly entangled, various parts going in different directions, but eventually the car came back together to be enjoyed by new owners. Dale Court took custody in Auckland, back in the area it had first travelled and been successful, around 1969, before it transferred to John Hearne in Mairangi Bay. Well over 80 years since it was exported, the car is now back in the UK, and if you would like to be its new owner, I have been told it is for sale.

TIME TO TAKE A SEAT

I have long been an admirer of these little Coventry-manufactured cars, and the Brooklands model in particular is somewhat iconic. When I was the Assistant Club Secretary of the British Racing Drivers Club, I spent much time in the archives looking at material from the BRDC 500 and events when Freddie Dixon was “the man to beat” in a Riley.

My drive in this particular Riley Brooklands came courtesy of Julian Sutton and the Historic Sportscar Collection, and knowing that the car is currently for sale, I came to the quick conclusion that this would probably be my only opportunity to drive the car that I have researched and understand to have a pedigree and to have lived such an interesting and active life in New Zealand.

My drive was arranged to take place at Silverstone on the day prior to the opening Vintage Sports Car Club meeting of the 2014 season. On arrival at the “Home of British Motor Racing” I was greeted by a paddock full of vintage and historic racers, all at the track for the annual test day organized by the Historic Grand Prix Cars Association (HGPCA), and I had fun looking through all the pit garages as I hunted out my drive for the day.

Meeting Julian I was given a quick tour of the car. My first impressions were good, the car looked like it was a true period vehicle, no modifications and in very period condition. The word patina is often used, sometimes too often, but in this case it was absolutely the right word to use. The whole car had a wonderful feel to it and I was pleased to climb aboard.

Instructed on how to “fire her up,” the Riley’s small engine burst into life easily and had an enjoyable engine note as I gently blipped the throttle. Getting used to the surroundings, I realized how close I felt sitting to the steering wheel, but actually this also gave me a feeling of security. The leather bolster seats of the car also felt secure, keeping me firmly in place and with a good degree of comfort as well.

Releasing the handbrake I then selected first gear—located forward in a reverse-style box (where third gear would normally be) and when given the signal by Julian, rolled the car forward out of the Silverstone pit box and onto the pit apron road. Accelerating down the pit lane, I selected second gear and started my drive!

The car pulled keenly as I pressed the throttle pedal, as I have already indicated my position in the snug little cockpit was very much “near the wheel,” and if a driver of above average height tried to drive a Riley Brooklands, then probably some alteration to the seat would be required, but for this drive I was comfortable enough, and my feet were able to access the pedals easily.

Despite having spent a quiet last few years, the Riley has undergone some recent mechanical workings, and as a result it felt like it wanted to be driven. There was slight play in the steering, but that was more down to the steering wheel mounting than any sloppiness in the steering itself, and for the speed I attained, the brakes were sharp with no drag.

The car revved nicely and the gears slipped in well, although the short gear lever away and in front of my left hand took just a small amount of getting used to. Once I had gained the confidence of driving a “back to front” box, as I had in the Bond Formula Junior for a recent profile, I was more than happy as I completed the test drive. After my time on the track, we carried out the obligatory car-to-car tracking shots and then the car was placed by the “Brooklands” gates outside the BRDC Clubhouse for some static images. It was here we replicated the Riley photograph from period when the driver was able to reach out of the cockpit and place his hand on the ground. Now, my arms are not short, but those present at Silverstone in our little posse think that the Riley PR department did a good job back then with their images, and probably removed the driver’s seat to allow him to sit slightly lower in the car. It was only a fingertip touch on the ground for me!

Driving away from the BRDC Clubhouse for my last turn behind the wheel of the Riley, I found myself reflecting on this car’s early pioneer antics in New Zealand. On a track as smooth as Silverstone one can imagine how difficult and arduous it must have been to race a car like this on dirt tracks for long periods of time. The car had a solid ride, and was fun to drive, and it felt like it wanted to be urged along. Really, I could say that this particular example felt very at home, but I think also that in many ways it did not! If the car could have spoken out to me then I believe it would have told me that it had heard of great feats by siblings on the tracks at Brooklands and Le Mans, but its heart was to be found chasing along the rugged roads of New Zealand. Back then in a golden era of competition it was tough, thrilling, exciting and speed meant fast. That was a time when this Riley Brooklands excelled and its drivers were heroes to many.

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis: Front engine and transmission, rear drive, on ladder frame chassis, with coachbuilt two-seater body. Evolved from Riley 9 family car.

Suspension: Beam front axle, semi-elliptic leaf springs, torque tube location, with friction type lever-arm dampers. Worm-type steering.

Wheelbase: 8-ft. 0-in. (243.9-cm)

Track: Front: 47.75-in. (121.3-cm) Rear: 47.75-in. (121.3-cm)

Engine: 4-cylinder in-line, with inlet and exhaust valves overhead, and opposed at 90-degrees.

Transmission: Single, dry-plate clutch, and four-speed manual transmission. No synchromesh.

Brakes: Drum front and rear brakes, actuation by cables and rods.

Wheels: 19-inch diameter

Tires: 27 x 4.40-inches front and rear

Fuel Tank: 10 imperial gallons (45.4-liters)

Acknowledgements / Resources

The author would like to thank Julian Sutton and The Historic Sportscar Collection for allowing me to drive this Riley Brooklands at Silverstone during the HGPCA Test Day. Julian was also most kind in allowing access to his extensive archive and collection of photographs.

Brooklands Volume II by W. Boddy – Grenville Production

Parry Thomas—Designer-Driver by Hugh Tours – Batsford Books

Riley—As old as the Industry by David G. Styles – David G. Styles Books

Riley Sports Cars 1926-1938 by Graham Robson – Haynes Publishing

Sporting Rileys—The Forgotten Champions by David G. Styles – Dalton Watson Books

The History of the Brooklands Motor Course 1906-1940 by W. Boddy – Grenville Publishing