If there’s one thing that sets a vintage racing car apart from a modern one, it’s the use of aluminum. The material had its own aura. Everyone knew the fastest XK-120s, the lightest Austin-Healeys and the quickest of the Ferraris, SL’s, Astons and Masers were distinguished by their lightweight skins formed from sheets of aluminum that had been pressed, rolled, formed or otherwise violently pounded into submission by gifted craftsmen around the world.

Aluminum had a number of things going for it besides being lightweight. It wasn’t particularly expensive and, in the right alloys, was relatively easy to form. On the downside, it hardens as it is worked and can get brittle. Many early aluminum bodies were attached to a steel framework with steel rivets, resulting in extensive corrosion problems down the road. Damaged areas were frequently patched with a dollop of Bondo rather than a time-consuming reshaping. By the time vintage racing came into being, most of the aluminum bodies from the 1950s were in need of some corrective surgery. However, there were only a few bodymen around the country that were familiar with the idiosyncrasies of working with aluminum, and those that could master the art became much in demand. One of the best of these craftsmen is Kent White, a.k.a. “The Tinman”.

Photo: Harold Pace

After studying at Bill Harrah’s fabled collection in the 1970s, White opened his own shop and began working on some of the highest-profile restorations of the cost-no-object 1980s.

By the 1990s, White began looking for new horizons to explore. Two things he never lost his love for were handforming aluminum and working with the acetylene welding torch. White felt the lowly gas torch had been given an unfair reputation and was superior for most applications to TIG (GTAW) welding. Not only was it much cheaper, but most amateur craftsmen working on vintage cars and homebuilt aircraft already had the basic rig sitting in a corner of their shop, just rarin’ to go. In 1989, he started a new company, TM Technologies, to revive the materials and processes of a bygone era.

Photo: Harold Pace

So how did he do it? First he developed effective eyewear to allow the welder to see through the yellowish flame that aluminum gives off when heated. Previous cobalt blue eyewear had been difficult to use and ineffective in preventing eye damage. The TM Green lenses soon became the standard for aluminum welding. He also found that many important fluxes and fillers were no longer in production, and he set about finding new suppliers for them. Soon he had a thriving business, providing tools and materials for all facets of sheet metal work, as well as acetylene welding processes. All that remained was to spread the gospel!

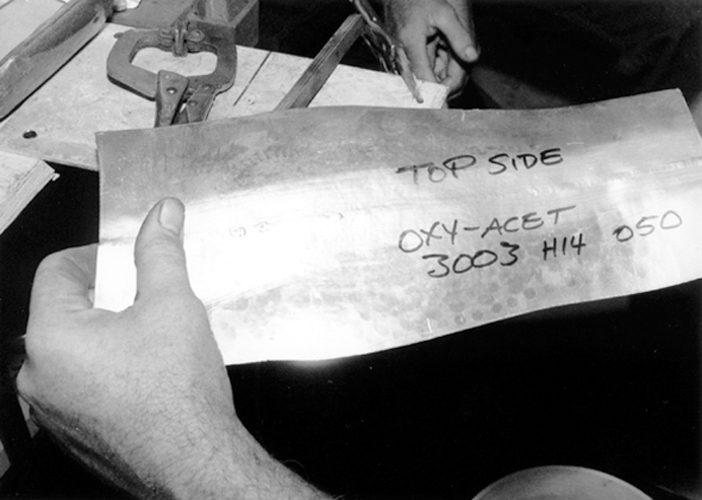

First question that comes up: Why oxy-acetylene instead of TIG? White says torch welding is faster, more economical, has superior penetration and workability, and the small, flat weld bead requires less finishing for a professional appearance. In order to get the same penetration with TIG welding, expensive back-purging (which involves flooding both sides of the weld area with gas) must be used to prevent contamination of the back side of the weld. Advantages of TIG? It will weld thick (over .090) materials better than a torch.

Photo: Harold Pace

However, most of us VRJ readers are not professional fabricators. We’re probably not going to fabricate suspension arms or aluminum roll cages from scratch. We’re looking for ways to weld up tanks, brackets, body panels, ducting and cooling/oiling system lines on a reasonable budget and with the control and pride that comes from doing it ourselves. Few will be able to rationalize a professional-level TIG system for the amount of aluminum work we do each year. But since gas rigs are common, inexpensive and versatile, they can be easily worked into the budget. After all, when it’s not welding up some lightweight doohickey, a gas welder can be joining mild steel, annealing a body panel for reworking, brazing up headers or loosening rusty hardware. Which brings up one of the cardinal virtues of oxy-acetylene welding – its versatility.

Recently, a group of expectant faces greeted White at one of his Houston stopovers. After the obligatory donuts and juice, White began by giving us the ground rules. For starters, not all alloys of any metal, including aluminum, are weldable. However, the most common types (like 3003 H14) used for race car fabricating are. White points out that different fluxes are needed for brazing than welding (some inexperienced welding supply dealers may try to tell you otherwise). Brazing fluxes contain zinc chloride, which will make the parent metal weak and brittle. Use only the best WELDING fluxes, like the revamped Alcoa fluxes sold by TM.

Photo: Harold Pace

A variety of torches can be used, although White recommends avoiding ones that are too large (“shipyard” torches) or too small (like jeweler’s torches). His personal favorite is the Meco Midget, an unusual torch shaped like a cigarette pack with the regulator controls on the top instead of the bottom. Very convenient, but White says the Victor torches are excellent as well. Start with a tip one size up from what you would pick to weld steel sheet the same thickness (metal thickness = tip orifice diameter).

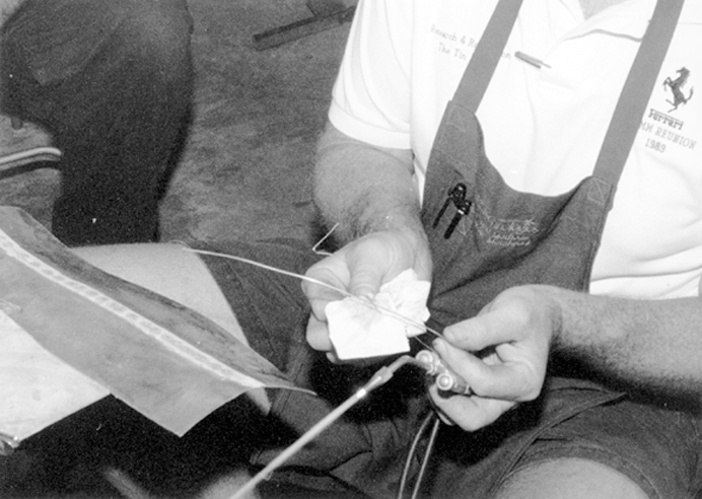

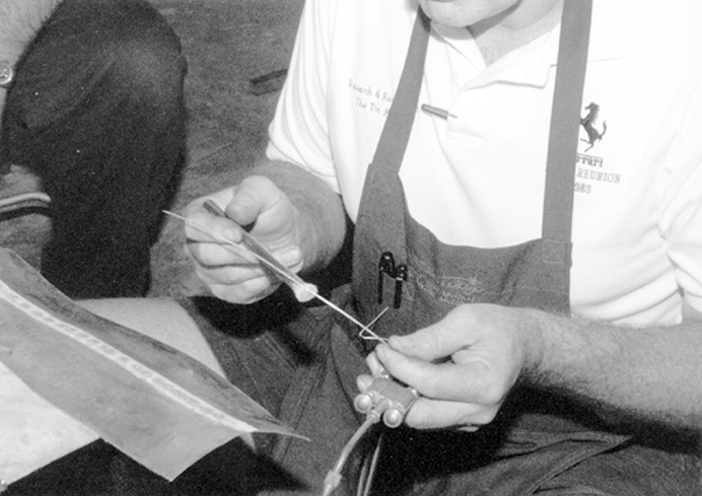

Now it’s cleaning time. If the aluminum is oily, clean with solvent, lacquer thinner or denatured alcohol (cheaper and more user-friendly than MEK). Then use a clean stainless toothbrush to scrub off the invisible layer of oxide from both sides of the metal. Then add flux powder to really clean water (in many areas this means bottled) and mix into a paste. This is coated onto the filler rod and/or the pieces to be joined. Choose a proper filler metal for your application that is no thicker than the panel to be welded. And don’t even THINK about those swap-meet rods that are supposed to weld anything together. According to White, they tend to crack as they cool and are actually intended for use on cheap pot metal.

Photo: Harold Pace

Make sure the regulators on your bottles are fully closed, then fully open both torch controls. Slowly open the acetylene bottle control until you can just feel a gentle breeze on your cheek. Light the torch (away from your cheek, natch) and slowly add oxygen at the bottle until you get a loud flame (more “hiss” than when welding steel). Now fine tune the size of the flame to the thickness of the material with the torch controls.

Now we are ready to tack the two parts together. Don your green goggles, set the flame a little hot, brush on flux and apply tacks about 1” apart, the length of the weld. If some tacks crack due to distortion, don’t worry about it. Then weld the joint together from one end to the other through the tacks. The welding itself is just like steel, except that the metal does not change color as it is heated. Your first warning of a burn-through is when the aluminum takes on a shiny, “molten” look. Ouch. Make sure there is nothing flammable/anatomical under the weld area, just in case! Distortion can be controlled by clamping, joint design, hammering or prying as you go.

Photo: Harold Pace

Now that your weld is completed, it must be cleaned to remove the flux. Start with hot (180°F) water and a stainless steel brush immediately after welding, followed by a liberal rinse with fresh water. Any flux left in pinholes will turn into a painter’s nightmare in about six weeks. If in doubt, play a torch (set at a neutral flame) over the weld area and look for the telltale, yellow-orange incandescence given off by flux residue. An invisible layer of oxide forms instantly on aluminum, and proper scrubbing with an etching solution will prevent paint problems down the road. Congratulations – you have gas welded your first aluminum part! Turn it over and check for penetration through to the back side. Practice, practice, practice is what makes perfect.

For those who can’t make it to a seminar, White also sells a 1-3/4 hour video on gas welding aluminum, shot through his green lenses so you can see what the flame is doing. TM also sells starter kits with the appropriate brushes, fluxes and filler materials for a variety of metal working projects.

TM Technologies

17167 Salmon Mine Rd

Nevada City, CA 95959

530-292-3506