1949 Kurtis Sports Car

Frank Kurtis and Custom Coachwork

Kurtis, the son of a blacksmith, was born in Colorado in 1908. His father repaired buggies and shod horses, but also worked on the automobiles that were growing in number. In 1922, the family moved to Los Angeles, where 14-year-old Frank lied about his age and got a job at the Don Lee Coach and Body Works, a company that specialized in building custom cars for movie stars. In 1919, Lee bought Earl Automobile Works, and Kurtis benefited from some tutoring in automotive design from Harley Earl, who worked with his father at Earl Automobile Works.

Kurtis built his first car, a 1916 Ford Model T with a custom body, for himself. In 1926, after being encouraged by friends, he began buying wrecked cars, rebuilding them with custom bodies, and reselling them for a profit. By 1930, he was gone from Lee’s firm and had started his own shop, although he continued to work for others. One of those he worked for in the ’30s was “Dutch” Darrin, but he only stayed there for a short time because his paychecks began bouncing. He built custom cars throughout the 1930s, including a three-wheeler for Joel Thorne, eclipsing the Davis. Possibly his first sports car was a Mercury-powered machine built for a Denver cattleman in the late 1930s. Significantly, he began building racecars in 1933.

Kurtis Kraft

Kurtis had observed that many of the Midget racecars were a handful to drive on the rough tracks of the early ‘30s. He speculated, correctly, that their problem was that they were too high and too tightly sprung. His design lowered the center of gravity and used softer springs. That way, he believed, the wheels would follow the track surface more closely, giving better traction and cornering. He also worked to reduce unsprung weight and installed adjustable torsion bars so his cars could be tuned for different track conditions.

In 1938, Kurtis built a Midget for Rex Mays. It was not only very successful, it was dominant! The demand for Kurtis Midgets resulted in the founding of Kurtis Kraft, Inc. In all, an estimated 550 complete Midgets were built, along with a similar number of kits. In addition to building racecars, Kurtis repaired them. He went to Indianapolis in 1939, where he was hired to rework and repair some of the racecars for the 500, and he decided to build his own car for the big race. His first Indy car was completed in 1941 for Sam Hank to drive. During World War II Kurtis produced materiel for the war effort, but he spent some of his time designing a new Midget that he would build once the war was won.

Kurtis was back at Indianapolis in 1946 with two of his cars—one for Ron Page and the other the famous Novi Special. While he continued to build Midgets, he would build a few Indycars for each year’s 500. He built one car, the Kurtis-Kraft Special, so that it could run on both dirt and paved short ovals, as well as the Indy 500. That car finished 9th in 1948. In 1949, now called the Wynn’s Oil Special and driven by Johnnie Parsons, the car took vitory, the first of many Indy 500 wins by Kurtis racecars.

Kurtis Sports Cars

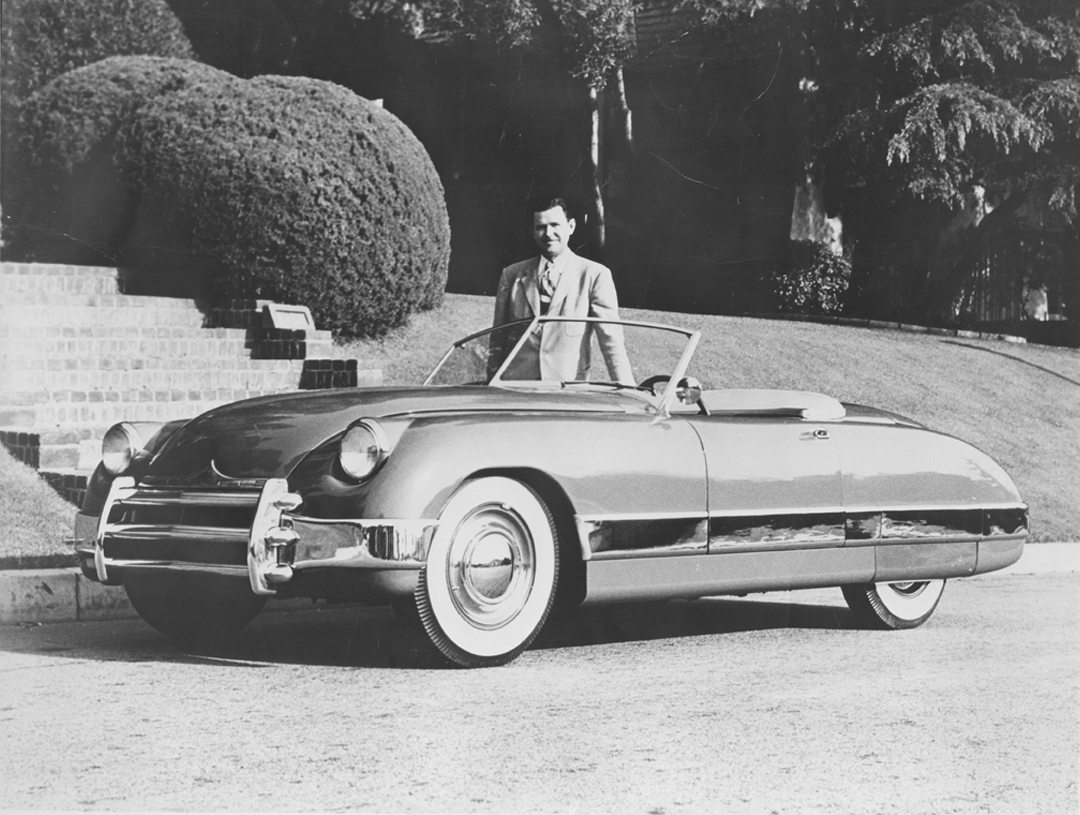

Kurtis built a customized Buick two-seater in 1948 and drove it to Indianapolis. The car made an impression on some significant people, including Benson Ford. Ford encouraged Kurtis to produce the car and even authorized the sale of parts to Kurtis for the car. The enthusiasm for his Buick special encouraged Kurtis to pursue building a production sports car. This wasn’t a new idea for Kurtis; he had long been interested in building a roadcar that had the power of an American engine and the handling of a European sports car. The dream became a reality when he partnered with Ed Walsh, a successful Kurtis Kraft racecar dealer. Together they formed Kurtis Sports Cars, Inc., a company operating separately from Kurtis Kraft. The modified Buick became the basis for the first Kurtis Sports Car.

The Kurtis Sports Car received considerable attention when it was announced. John Barclay wrote about it in the January issue of Speed Age magazine, saying, “It will be America’s first and really exclusive sportsman’s road car since the Stutz Bearcat. There will be no compromises…. Instead, they will be specifically designed for speed with the combined safety factor of a track racer…. The projected sportsman’s special will have a factory warranted speed of 150 mph….” When Tom McCahill of Mechanics Illustrated saw the prototype, he wrote “It has speed, safety, luxury and dazzling class.” Bud Winfield, a veteran racer, reported in the February 1949 issue of Hot Rod magazine that the car had “remarkable handling characteristics that may well compete with that of foreign sportsters.”

The car was produced as a kit and as a completed car in either a standard or deluxe configuration. The kit was priced at $1,495 and the complete car at $3,495, although a fully optioned deluxe model could cost as much as $5,000. Differences between the models included Ford gauges for the standard and Stewart-Warner gauges for the deluxe. Stock Ford crate engines were used in the standard, while there were performance options for the deluxe. Both models had a leather interior and padded top. Both were very nice road cars with plenty of power and a nice comfort level.

After two prototypes were built, Kurtis began the production run. Unfortunately, only 16 more cars and two kits were built, the last of which became a high school graduation present to Kurtis’ son Arlen, along with two kits. While Walsh had promised to provide funds for the venture, he never came through. Kurtis Sports Cars was a business for Kurtis, but apparently it was only a hobby for Walsh. Eventually, cash flow problems could not be overcome.

Enter Earl “Madman” Muntz. Muntz had been quite successful selling televisions; at buying used cars in the Midwest, shipping them out to California, and selling them for a profit; and as a Kaiser-Frazer dealer. Muntz wanted to have a car with his name on it, and Kurtis Sports Cars was available. Kurtis sold the rights and all the tooling for the Kurtis Sports Car to Muntz in 1950 for $75,000. Initially, Kurtis built the cars that were now called Muntz Jets, but the production was moved to Illinois where Muntz was based. Kurtis built 15 of the Jets and ten bare chassis. When Muntz took control in 1950, he made changes. The most dramatic change was lengthening the car by 13-inches to make it a four-seater. Muntz also decided to use steel instead of aluminum everywhere to save production costs and reduce the price of the car. To offset the added weight, Lincoln V12 or Cadillac V8 engines were installed in these larger cars. Kurtis served as a consultant to Muntz until he resigned because he could no longer tolerate the increased size, weight and poor workmanship of the cars produced in Illinois. While Muntz produced more cars than Kurtis, a total of 394 Jets, timing was not in his favor. The Kurtis Sports Car came out at the same time as the Jaguar XK120, an arguably more attractive car. While both Kurtis and Muntz believed that could be overcome, the Muntz Jets were subsequently faced with some significant American competition. Both Ford and General Motors had begun developing their own two-seat sports cars. Knowing this, Muntz decided to build the Muntz Roadster. Unfortunately, when the Corvette was shown at the 1953 Indianapolis Sports Car Show, the Vette got all the attention and the Muntz got very little. It was estimated that each Muntz Jet cost more to produce than its sales price. With an inability to compete with the Corvette and facing a loss for each car he built, Muntz eventually decided to end production of his version of the Kurtis Sports Car.

KB0003

The first production Kurtis Sports Car was given the serial number KB0003 when it was built in 1949. It was green with a tan top and tan interior. It had a Ford flathead V8 with a serial number B1 894. While KB0003 had a Ford engine and transmission, it used a 1949 Studebaker Champion differential and 1948 Studebaker Champion wheels and

modified front axle. It was a high-end deluxe model, so it had all the extras associated with that model. The car had the full array of Stewart-Warner gauges including a tachometer, adjustable leather bucket seats, Plexiglas side curtains and a floor shifter with Warner Gear overdrive. Kurtis was an expert when it came to designing a suspension for good roadholding, as he proved with his racecars. Spring rates, shock absorber settings and weight distribution were all considered when designing the suspension for his sports car.

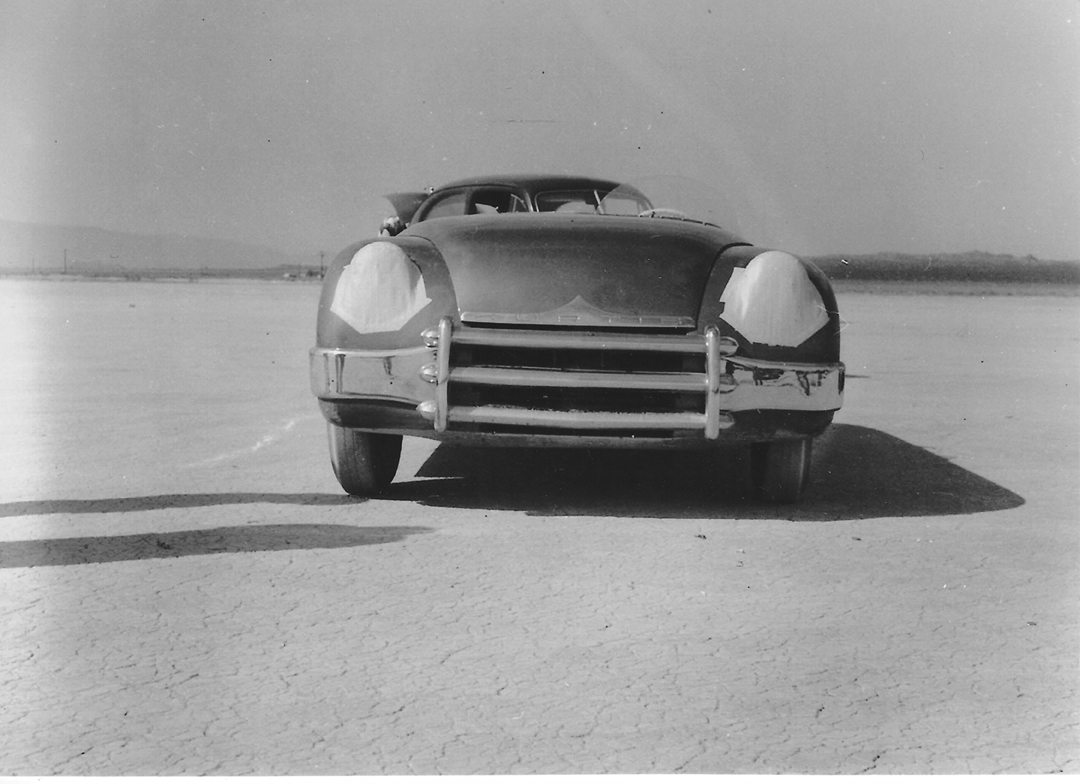

A first production version of any automobile is always significant, but this car is significant in other ways as well. It was the first cover car for the then-new Motor Trend magazine. It was also used to set a land speed record at the Bonneville Salt Flats, driven by Wally Parks, the first editor of Hot Rod magazine and founder of the National Hot Rod Association, NHRA. Parks drove the car to a two-way average of 142.515 mph on

August 27, 1949, beating a Jaguar XK120 by nearly 10 mph. Being faster than the Jaguar was important to Kurtis, who saw the Jag as the most significant competition to his car. Unfortunately, the record made little difference, as the Jag outsold the Kurtis by a lot.

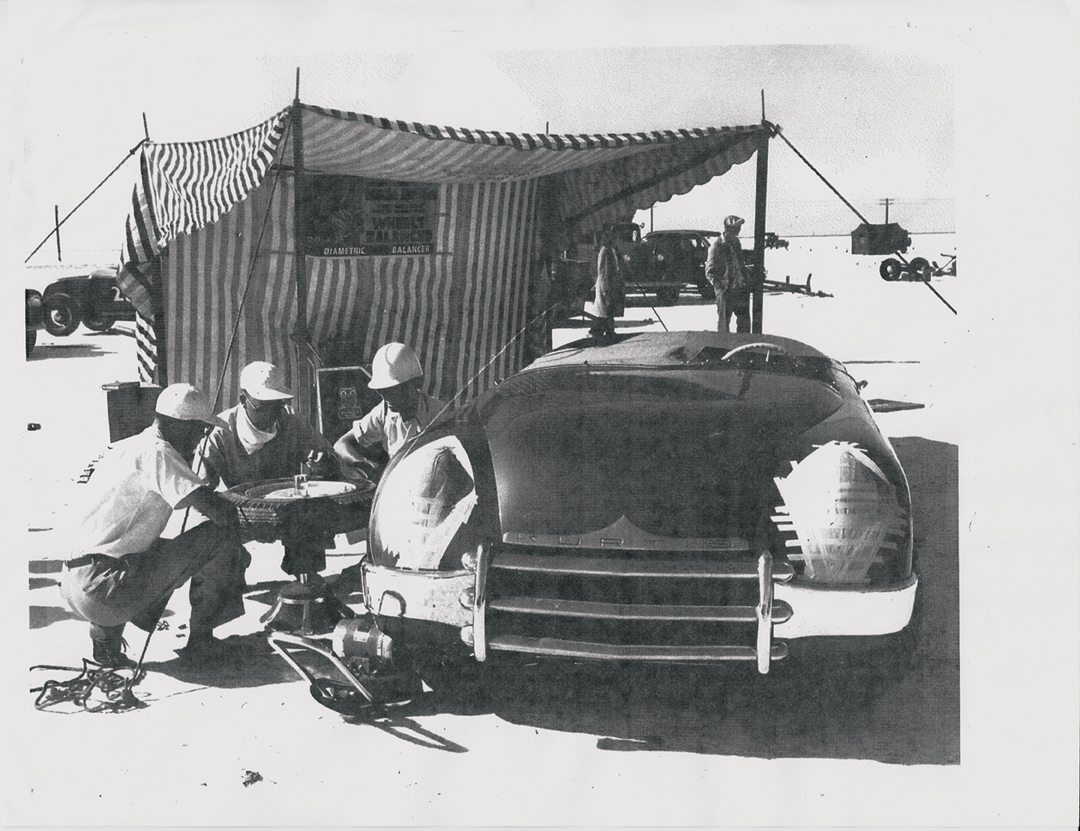

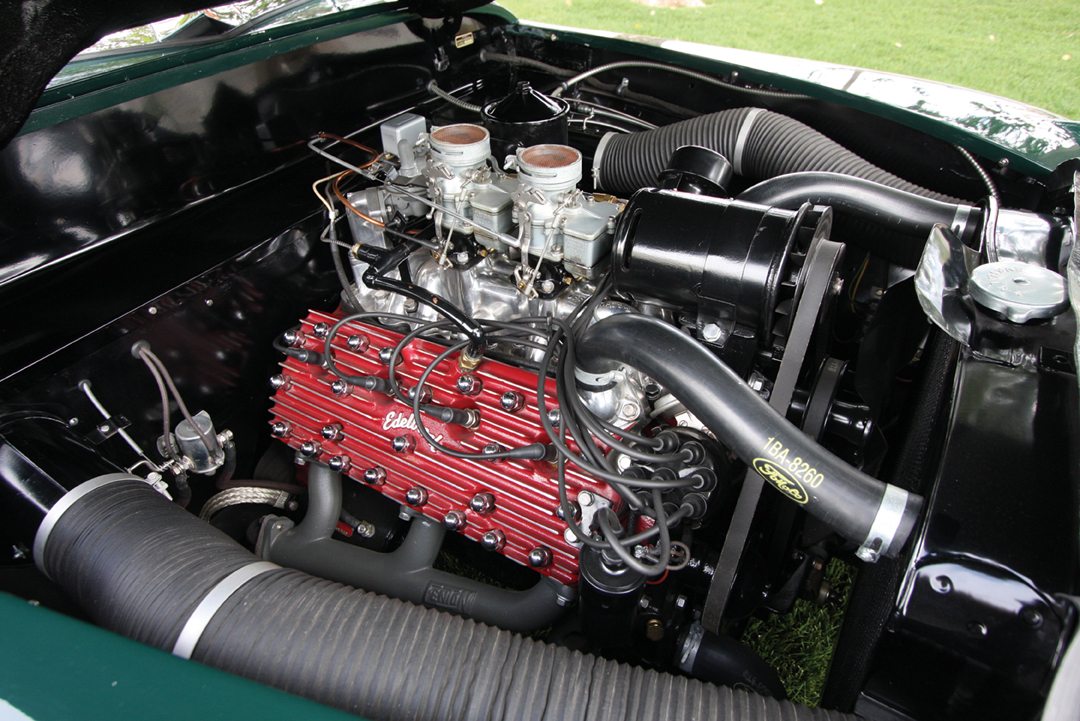

KB0003 needed a special engine to set the land speed record, so Kurtis had one built by Bobby Meeks, engine builder for Vic Edelbrock. The 239-cu.in. Ford V8 used Edelbrock heads and two Stromberg 97 carburetors on an Offenhauser intake manifold—Edelbrock had not yet designed his own intake manifold. It had a dual ignition by Spaulding, hotter camshaft and Fenton exhaust headers. Pistons and crankshaft were Mercury, bore and stroke were 3-5/16-inches and 4-inches, respectively, and the compression ratio was 10.5:1. An engine built to the same specifications later hit 380 bhp on the dyno. A Ford truck oil pan was used because it held an additional quart of oil. The car was equipped with a pressurized fuel tank mounted in place of the passenger seat and using the same bolt holes. Belly pans were also installed to help the aerodynamics.

The car was taken to Rosamond Dry Lake in California for a shakedown prior to going to Bonneville. Kurtis got it up to 130 mph, just short of the record set by Jaguar earlier that year. Kurtis wanted to beat the Jaguar record, however, so a team was created for the Salt Lake attempt. Wally Parks would drive, Meeks and Edelbrock would watch over the engine, and Frank Kurtis would watch over everything.

The first qualifying run on the Bonneville salt was disappointing. Parks only ran 128.57 mph. After returning to the pits, Parks learned that the car had overdrive, which he used for subsequent runs. His second qualifying run was at 131.19 mph. It all came together for the record run. His fastest speed was 143.08 mph down and 141.95 mph on the return, for an average of 142.515 mph and a new land speed record for the class. To add a bit more validation of the car’s potential, Dean Batchelor was able to run the car at over 140 mph after Parks set the record.

There was one other discovery after the record run. Parks had been told to keep the engine speed at about 6,000 rpm, but he reported that he could only get 3,500 rpm from the engine. It was then discovered that Kurtis had installed a marine tach drive that read half the true engine speed! Parks had actually been turning 7,000 rpm when he set the record.

After the record run, KB003 was returned to California, where it was kept by Kurtis Kraft as a promotional vehicle. Its hot engine was replaced by a Ford 8 AB flathead engine that was considered more “streetable,” and the original engine was stripped of its speed equipment for other projects. Arlen Kurtis used some of the engine’s internals to improve the performance of his car, KB018. Apparently KB003 was still impressive, based on comments in the car magazines of the time. Road & Track’s John Bond said he believed it could outhandle a Jag XK120, something Kurtis was pleased to hear. There were also favorable comments in Mechanics Illustrated, where McCahill noted that the car was “far more comfortable than most foreign cars and takes the bumps smoothly,” and Motor Trend said it had “all the fetures a sports car should have: Speed maneuverability, acceleration, power and sleek looks.”

After Kurtis sold KB0003, it had quite a few owners, some of whom didn’t take very good care of this historic automobile. Thanks to DeWayne Ashmead, the current owner and the man responsible for properly restoring this car, a pretty good history of the car has been developed. Harry Birdsall bought the car from Kurtis and raced it, overheating and destroying the engine. It then went to someone in Colorado who installed a Cadillac engine and registered it as a Cadillac because of a state requirement that a car be registered according to the engine it used. In 1960, it went to Kansas, where Bill Bottorff experienced a brake failure and crash that destroyed the windshield, hood and rear deck lid, and damaged the left rear and right front quarters. After the wreck, the car passed to a succession of owners who believed they could restore it. Unfortunately, they were all unsuccessful. It wound up with an automobile broker in St. Louis, Missouri, in 2004.

After reading an article about Kurtis Sports Cars, Ashmead decided that he wanted one. After searching for years, he got a call from the St. Louis broker. The broker had just bought one, and it was offered at a reasonable price. The car was supposedly 95 percent restored, although, as Ashmead discovered, it was closer to being a basket case than a restored car. Apparently, no one had researched the car’s history, so Ashmead began the effort to determine what was original on this car. He found the VIN, which led him to discover that it was the first production Kurtis Sports Car and the car that set the land speed record in 1949! Ashmead called it “dumb luck,” but luck is usually the result of hard work—work that Ashmead had done.

Ashmead contacted Arlen Kurtis and Wally Parks, who agreed to act as consultants on the restoration to 1949 land speed record specifications. He learned that it was the only green Kurtis built, found odd holes in the frame that were for the Bonneville belly pans, and learned that the Stewart-Warner tach was one that ran off the crank not the generator. The Peterson Automotive Museum had two Muntz Jets with the same interior that KB0003 once had, so he was able to copy them and have a new interior produced. Arlen Kurtis proved to be an important source of parts. He had an original windshield frame and hubcap rings that Kurtis had produced to hide the word “Ford” on the car’s hubcaps. Headlights from a 1949 Chevrolet truck were installed. Ford and Studebaker parts cars were cannibalized for driveline parts. Finally, the Ford engine was built to original specifications for the record run. When the car was done, Wally Parks signed the glovebox door,

something he never did on any other car. Both he and Arlen Kurtis were very pleased with the result Ashmead had achieved.

Driving Impressions

My first impression after sliding into KB003 was that this is all familiar. It is a very comfortable car, the gauges are familiar, pedals are positioned nicely, and your hand falls right on the shifter. Second impression was “oh my,” as the engine responded immediately to the key—what a nice sound the hot rod flathead Ford makes, and that’s at idle! Third impression was “Yeehaa,” as I got on the gas after pulling away from the shop. This is a relatively heavy car, so I can’t call the acceleration “neck snapping,” but it was enough to put a smile on my face. Fourth impression was “whee,” as I took the first corner at moderate speed. This car corners flat! Kurtis really knew what he was doing with his suspensions. The engine has plenty of torque, so acceleration is good in every gear, and from just about any engine speed. The ride, well it’s just nice and smooth. This would be a great car for a road trip, and it was built in 1949!

Road construction limited where I could drive the car, so most of the experience was though a new housing development, but this is a rare automobile I’m driving, so speeds had to be kept in check anyway. I never did get to use the overdrive, but there was a nice straight stretch between the shop and the development that allowed me to take the car up through the three gears to a speed “somewhat” over the posted limit. In the development, there were numerous opportunities to test the

handling on both left and right 90-degree corners.

This is a car that would be great on a tour like the Colorado Grand. It is quick, handles well and will not beat you to death. In fact, the only downside from traveling 1,000 miles in KB0003 would be the sore jaw muscles from smiling so much.

Epilogue

Frank Kurtis left Kurtis Kraft in 1956 to form the Frank Kuris Company, where he could operate without the interference of business partners. He still built racecars, but as the rear-engined revolution took hold at Indy, he decided to retire in 1968. His son, Arlen, took over the business and won a major contract with the U.S. Air Force to build the Start Carts for the SR-71 Blackbird spy plane. He also built high-performance boats for drag racing and water skiing. After selling the boat business in the ‘80s and the end of the SR-71 program in 1989, Arlen began building

reproductions of his father’s cars, including some of the unique parts for those cars.

Frank Kurtis built some incredibly important racecars. He also built a few significant sports cars, especially KB003.

Specifications

Body: Steel with some fiberglass panels

Chassis: Welded steel

Wheelbase: 100-inches

Track: 56 inches front and rear

Length: 170-inches

Height: 48-inches

Weight: 3780-pounds

Suspension: Independent with transverse springs in front

Engine: Ford Flathead V8 with Edelbrock heads

Displacement: 239-cid / 3917-cc

Bore/Stroke: 3-5/16 inches/4-inches

Compression: 10.5:1

Power: 100 bhp at 3600 rpm

Induction: Dual Stromberg carburetors on Offenhauser intake manifold

Transmission: Ford 3-speed with Warner Gear overdrive

Differential: Studebaker Champion

Brakes: Studebaker Champion drums

Wheels: Studebaker wheels with Ford hubcaps with special rings to cover the word “Ford”