1976 March 76B

I have a confession to make. When I was but a pubescent young man, I used to lie in bed at night and fantasize…that I was Gilles Villeneuve. In an era before in-car cameras, I could close my eyes and visualize a complete lap of the U.S. Grand Prix course at Long Beach, with me behind the wheel of a Ferrari 312 T4—Villeneuve’s T4 to be precise. I’d like to think that we all have particular cars and drivers that, for some inexplicable reason, captured our imagination at a particularly impressionable time in our lives. Regardless of how odd or irrational it may be, these early impressions can stick with us for a lifetime.

For me, it was watching Villeneuve for the first time at Long Beach in 1978. Even to my young eyes, I could tell that he was driving at—and often over—the limit, lap after lap, around a completely unforgiving, concrete-lined, temporary street course. His driving seemed impassioned, sometimes reckless, and completely mesmerizing. As the years progressed, his on-track exploits became legendary. To this day, I would still contend that there has been no more exciting piece of driving, in any race series, than the multi-lap battle between Villeneuve’s Ferrari and Rene Arnoux’s Renault in the closing laps of the 1979 French Grand Prix. Look it up on YouTube, and if it doesn’t get your heart racing, nothing will.

Photo: Jim Williams

Sadly, my hero worship came to a crashing halt on May 8, 1982, when Villeneuve, in consummate style, made a final banzai qualifying lap for the Belgian Grand Prix and got tangled up with a slower car, rocketing Gilles into the air and an early grave. The candle that burns twice as bright, burns twice as fast.

Flash forward 35 years and as a middle-aged man, I recently get a call, “Would you be interested in test driving the March that gave Gilles Villeneuve the 1976 Atlantic Championship and launched his Formula One career?…Are you still on the line??” It didn’t take the paramedics more than a few minutes to resuscitate me.

Ides of March

Photo: Jim Williams

By end of 1968, the era of the “Garagiste” (as Enzo Ferrari used to call them) was in full swing. That is to say, a couple of blokes could buy a Cosworth DFV, a Hewland gearbox and some of the off-the-shelf suspension pieces available from Lotus or Brabham, and if they were handy with sheet metal, could fashion themselves a Formula One car in any one of a million tiny garages across the UK. Many soon to be great names in Formula One started out in just such a manner.

At this same time a barrister named Max Mosley was deciding what to do with his motor sport life. He had raced in Formula 2 for several years with limited success and after realizing, according to Mosley, “…it was evident that I wasn’t going to be World Champion,” began looking for other outlets for his motor sport passion.

Photo: Jim Williams

At the same time, designer Robin Herd was also at a crossroads. Having designed a special Cosworth 4-wheel-drive Formula One car for Jim Clark (who perished before completion) and having been chief of design at McLaren, the brilliant designer was entertaining offers from nearly every F1 manufacturer but Ferrari. While he could work for nearly anyone up and down the pit lane, he yearned to have a stake in his own team.

While the two tangentially knew each other while studying at Oxford, they met one fateful night at Frank Williams’s tiny garage, hit it off and during the ensuing meal together mutually agreed that the world could do with another racecar manufacturer.

Unbeknownst to Mosley, Herd had been having similar discussions with two other friends, Alan Rees a retired driver who now worked in team management, and Graham Coaker, an F3 driver and engineer. In the end, Herd came to the conclusion that if he were to start his own company he would need a man with Rees’s management abilities, an engineer like Coaker who understood the production side of building racecars and a smooth frontman like Mosley, who could handle the legal and commercial aspects of the business. By May 17, 1969, the four had formed MARCH (Mosley, Rees, Coaker, Herd).

Marching Orders

At the outset, March’s intentions were to build and sell production racecars as way to finance the construction and campaigning of a Formula One car. With this goal in mind, the first March was an F3 car, which made its debut in 1969. This initial racecar was known as the 693 and set the groundwork for March’s simple nomenclature system, whereby any particular car’s name incorporated first the year, and then the formula, i.e. the 693 was a 1969 F3 model, whereas the 701 was a 1970 Formula One car and the 752, a 1975 F2 car, etc.

March’s 693 was a fairly straightforward design featuring a square-tube spaceframe that utilized numerous suspension parts (uprights, etc.) sourced from Lotus and Brabham. In its racing debut, Ronnie Peterson drove it to an impressive 3rd place at Cadwell Park. While the 693 did not ultimately enjoy enormous success, it got March off the ground and, from a design perspective, formed the foundation for the F2, F3, Atlantic and Formula Ford production racecars that would follow over the next 10 years.

Photo: Jim Williams

For 1970, March built its first Formula 2 car, the 702, as an evolution of the 693. However, its tubeframe design and resulting heavy weight made it uncompetitive. As a result, the following year Herd designed an all-new, monocoque chassis for the 712, which featured a semi-stressed engine supported by a tubular subframe. In the hands of Peterson, the 712 handily won 10 races and swept the 1971 European F2 championship.

While the success of the 712 was a boon to March’s image, its finances were a different story. The year 1970 brought March’s introduction into Formula One with the 701. Though the 701 showed promise, if not moments of brilliance, in the hands of drivers like Peterson, Stewart and Andretti, the cost of development was high. With only one win and a 3rd place in the championship, March did not enjoy the tide of sponsorship it was hoping for, resulting in the F1 program draining the company’s extremely limited resources. These early financial difficulties created no small amount of stress between the four founders. Mosley and Herd had their passion and focus based in the Formula One program, and so felt that all other aspects of the company needed to subserve the F1 car. Alternatively, Coaker and Rees felt that without a solid production racecar business first, there would be no March and therefore no Formula One program to support. By the end of the 1970 season, this internal conflict reached a high enough pitch that Coaker resigned only 12 months after March was founded. Just a year later, Rees would follow.

Atlantic Dawn

Photo: Fred Lewis

In addition to winning the F2 championship, 1971 also brought about a new development that would influence the fortunes of March for the balance of the ’70s. That same year, Brands Hatch promoter John Webb unveiled a new, national-level racing category designed to provide F2 level performance, on an F3 budget. Webb’s new category was called Formula Atlantic and was, in many ways, an extension of the Formula B category that had been popular in the United States since 1965. Webb reckoned that by putting 1600-cc, twin-cam engines, in existing F2 and F3 chassis, an exciting, high-performance open-wheeler could be created without the extreme expense associated with the more sophisticated F2 engines of the period.

That first season an ambitious schedule of 24 races was held with Australian Vern Schuppan taking home the inaugural championship driving a Palliser. However, at the second race of the season, the March 21st event at Oulton Park, American Bill Gubelmann won at the wheel of a March 71BM, which was a variation of the 712 F2 car intended for the American FB championship. A week later, Dave Morgan won the Mallory Park round driving a 702 with Vegantune-prepared Ford twin-cam power. And finally, in the season ending Yellow Pages Trophy Race, John Nicholson claimed victory at the wheel of another converted March 702. For March, clearly there was a future in this new Atlantic category.

March Everywhere

Photo: Fred Lewis

By 1972, March was building cars for Formula One, F2, F3, FAtlantic, FB, F5000 and FF. For 1972, the new 722 F2 car received updated bodywork and a chisel nose, but it could not replicate the dominating success of the 712. However, in Atlantic guise, Gubelmann drove the 722—now equipped with the new Ford BDD engine—to the 1972 British Yellow Pages Atlantic championship.

With the next year’s 732, March went back to a closer variation of the 712. Thanks to the driving of Jean-Pierre Jarier the 732 proved almost unbeatable, as he chocked up seven of March’s 11 F2 victories that season and swept to the title. In the British Atlantic series, four of the top five championship finishers drove Marches, with Colin Vandervell claiming the crown at the wheel of a 73B.

In 1974, March tried something new and developed a “factory” 742 car that featured side-mounted radiators, revised suspension geometry and a full-width, bluff nose cone, while the “customer” 742 was merely an update of the 732. The factory cars of Depailler and Stuck swept 1st and 2nd in the F2 championship, but March created a legion of angry customers in the process. In the Atlantic arena, two separate series formed in the UK, one sponsored by Southern Organs and the other by John Player. In the Southern Organ Series, Australian newcomer Alan Jones looked to have the championship tied up, in his March 74B, until the final race when Scot Jim Crawford (who drove a March for part of the series and a Chevron the balance) won the final race which counted for double points. By this time March chassis occupied over a quarter of the grid, in either series.

Marches and Snowmobiles

Photo: Marc Sproule

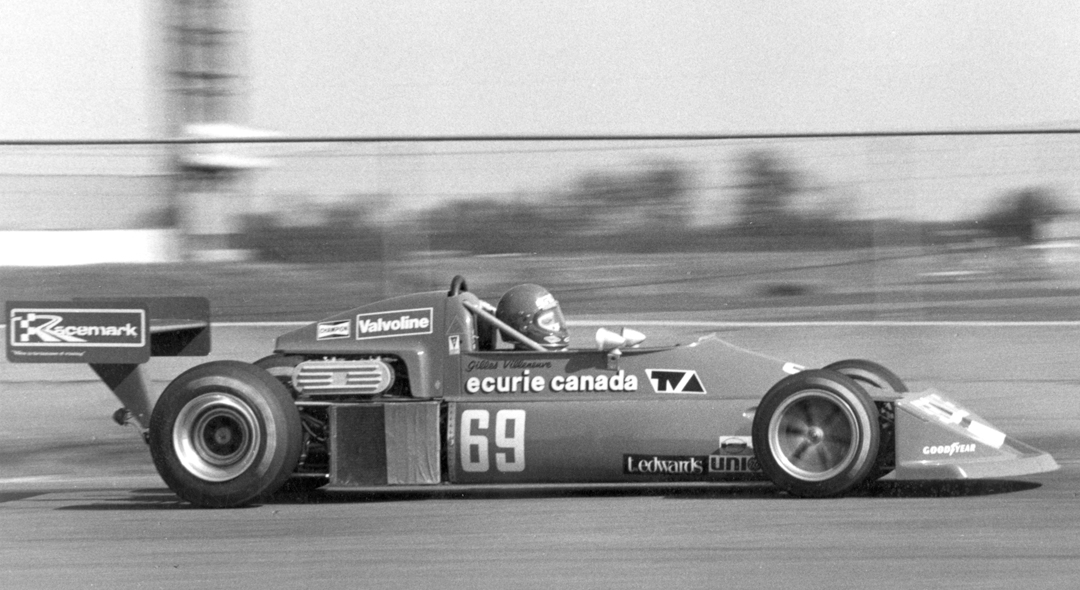

Perhaps due to the SCCA’s hesitancy to abandon its closely related FB category, Atlantic didn’t make its North American debut until 1974, when Canada’s CASC launched the Player’s Challenge for Formula Atlantic. That first year’s championship was claimed by Canadian Bill Brack, in a Lotus 59/69, while the majority of the field was made up of either Lolas, Lotuses or Chevrons. However there was a new team campaigning the March 74B that first year. This team, Ecurie Canada, was owned by a Montreal-based racer and entrepreneur named Kris Harrison. One day a young French-Canadian came to see Harrison at his shop. According to Harrison, “This kid walked in, introduced himself, and ordered a driving suit and some gear. Then he said he wanted to drive in Atlantic and asked me what it would cost. I told him I wasn’t interested in anyone who wasn’t experienced. Before he left he told me to call Jacques Couture.”

Couture was the head driving instructor at the Jim Russell School at Mt. Tremblant. Couture went on to tell Harrison that this kid named Gilles Villeneuve was a multiple-time snowmobile champion and a recent graduate of his course. While he had only competed in 10 Formula Ford races total, up to that point, Couture told Harrison to sign him, as he was sensational. A week later Gilles was on the Ecurie Canada team as a paying driver, though according to Gilles, “I didn’t have a penny. When I think about it I wonder how I made it.” Of course he made it by selling his house, which did not go down well with his wife, Joann, when he informed her!

Photo: Marc Sproule

Villeneuve’s season started off well enough, with a 3rd place at Westwood, but the following five races of the series he either crashed, or DNF. Though Harrison invited Villeneuve to return for the 1975 season, problems raising the necessary sponsorship in time meant Villeneuve missed out on the drive as Harrison signed Bertil Roos and Craig Hill instead. Completely despondent and on the verge of throwing in the towel, Villeneuve’s wife told him to order a car as she couldn’t stand to see him so depressed. Just three weeks before 1975 Player’s Championship was to start, Villeneuve ordered a new March 75B and a Ford BDD engine. He was now not only going to be the driver, but the team manager, mechanic and truck driver as well. Fortunately, just a week before the first race, Villeneuve worked out a sponsorship deal with his old snowmobile manufacturer Skiroule to allow him to pay for the car and a mechanic to help on race weekends.

The first race at Edmonton Villeneuve finished a lowly 15th, but for the next race at Westwood he was able to improve that to 5th. Then the show moved to Gimli in Manitoba, where Gilles struggled with mechanical problems that left him an unfortunate 19th on the grid. Then something happened that would forever change the arc of Villeneuve’s life…rain began to fall.

Not only did it rain, but it poured. Whether through desperation, determination or training from racing snowmobiles in blizzard conditions, Villeneuve drove like a man possessed as he charged his way up through the field. According to Gilles, the conditions were “worse than a nightmare. I’ll never forget that race. I felt I was given a chance that would never happen again.” Despite slewing off the track several times, Villeneuve went on to a commanding 15-second win over the 2nd place finisher, a young American up and comer named Bobby Rahal. Villeneuve backed this virtuoso performance up at the next race at St.Jovite, where he finished 2nd to Elliott Forbes-Robinson. Capping off this breakthrough season, Villeneuve qualified a stunning 3rd for the end of season non-championship race at Trois-Riviéres, Quebec, despite the presence of Formula One drivers like Vittorio Brambilla, Jean-Pierre Jarier and Patrick Depailler. At the start of the race, he shot past Depailler and proceeded to hunt down leader Jarier until his March’s brakes expired on the 60th lap. While he didn’t finish, he put everyone on notice that he would be a force to be reckoned with in the years to come.

Magic Season

Photo: Z Collection

With his electrifying performances in 1975, Gilles received numerous offers for rides in 1976. Among these were offers from Ecurie Canada and Doug Shierson Racing. While Shierson’s offer was attractive, it involved Villeneuve being teammate to Bobby Rahal, but Villeneuve decided he wanted to go to a team where he would be the full focus. As a result, Gilles re-signed with Harrison’s Ecurie Canada during the October 1975 Watkins Glen Grand Prix weekend. Another key factor in Villeneuve’s decision was the fact that Harrison was bringing former March race engineer Ray Wardell, who had worked in both March’s F1 and F2 programs, into the team.

For 1976, a second North American Formula Atlantic championship was added when IMSA scheduled a six-race series to run complementarily with the Canadian CASC Player’s series. The year’s first race was at Road Atlanta on April 11, where Villeneuve —driving the chassis you see on these pages, March 76B-3—claimed the pole and stormed off to a 13-second victory over runner-up Tom Pumpelly. Several weeks later at Laguna Seca, on May 2, Villeneuve started from 3rd on the grid, but again ran away from the competition to finish over a minute ahead of 2nd place finisher Elliott Forbes-Robinson. Results were much the same a week later, when the IMSA series stopped at Southern California’s Ontario Motor Speedway. This time Villeneuve chocked up pole, fastest lap and another victory over Forbes-Robinson. According to Vileneuve, “I think three things have made me better this year. The car is better prepared, I have had a chance to drive a lot more often than last year, and with not working on the car I am more rested and have more time to think about what is going on while I am at the track.” Gilles added, “My team manager, Ray Wardell, and I are beginning to understand each other more and more with each race. We are improving our relationship.”

The racing now moved back north to Canada, and much to the competition’s chagrin, Villeneuve and Wardell did indeed seem to understand each other more and more with each race. Gilles claimed the pole and the win at Edmonton on May 16. At Westwood, on May 30, Gilles again took the pole but suffered, according to him, an uncharacteristic sticky throttle that relegated him to a lowly 19th position finish. However, that was the last break his fellow competitors would receive the balance of the year. Villeneuve went on to take the pole and the win in the next two rounds at Gimli on June 13 and St. Jovite on July 11. However, after St. Jovite, Villeneuve and Ecurie Canada had a scare when Villeneuve’s sponsor, Skiroule Snowmobiles, declared bankruptcy and bounced one of their sponsorship checks. Despite their dream season, team principal Harrison was adamant that without sponsorship they could not finish the season. Fortunately, just a week before the August 8 Halifax round, a savior came through in the form of Montreal businessman Gaston Parent. With his March repainted from Skiroule green to white with a fleur de lis (a logo designed by Parent’s company for the city of Montreal), Villeneuve returned to the track and his usual form by taking pole and the win, and in so doing capturing the 1976 CASC Player’s Championship.

Photo: Z Collection

On September 15 Villeneuve and company returned to Trois-Riviéres for the season-ending, non-championship street race. Like the year before, numerous Formula One hot shoes were flown in to spice up the caliber of the field including Alan Jones, Patrick Depailler, Vittorio Brambilla and soon to be World Champion James Hunt. Hunt and Depailler were to run Marches prepped by Ecurie Canada, while Villeneuve’s car would now run with sponsorship from Direct Film, which had contributed money to help Villeneuve make the event. Despite struggling with an ill-handling car Villeneuve took the pole and on race day shot out to a commanding 10-second lead that he never relinquished. Villeneuve won ahead of 2nd place finisher Alan Jones and 3rd place finisher James Hunt. Hunt was so startled by Villeuenve’s speed and daring that when he returned to England he told McLaren principal Teddy Mayer and sponsor Marlboro, “Look, I’ve just been beaten by this guy Villeneuve and he’s really magic. You really ought to get hold of him.” In December of that year, it was announced that Villeneuve would become a part-time driver for McLaren, a move that would launch him onto the Formula One scene and set the stage for his historic move to Ferrari.

The only piece of unfinished business left on Villeneuve’s 1976 plate was to wrap up the IMSA Atlantic championship, which he intended to do at the September 19 round at Road Atlanta. This left Villeneuve the final round, at Laguna Seca, as insurance in case something went wrong. However, the trip west would never be needed as Villeneuve claimed pole, fastest lap and handily beat 2nd place finisher Tom Gloy to the checkered flag. Interestingly, Villeneuve’s year-long ride, chassis 76B-3, would go on to take an unusual detour.

For the Road Atlanta round, Ecurie Canada gave the second team March to Howdy Holmes to race. Holmes had a major accident coming through the big downhill, right-hander. The damage was significant enough that the team had to go by Doug Shierson’s warehouse to get parts, as he was the U.S. March importer at that time. But much to the team’s surprise, when they got there, Shierson informed them that since Holmes’s chassis had been on loan to Ecurie Canada from him, he wanted a car back…and not the damaged one! With both championships wrapped up, and Villeneve’s winning car being the only whole car they had, they handed it over to Shierson.

The March Marches On

Photo: Fred Lewis

Shierson took chassis 76B-3 and promptly rented it out to Tom Pumpelly for the SCCA Runoffs, which were being held that year at Road Atlanta. However, after changing the engine, Pumpelly’s team neglected to tie off the rear brake line, which Ecurie Canada had routed beneath the engine. As a result the steel braided line dragged on the Road Atlanta asphalt until it wore through, resulting in Pumpelly having a huge “no brakes” shunt at Turn 6, essentially writing the Villeneuve championship car off.

Californian Jon Norman was also racing at Road Atlanta that fateful weekend. According to Norman, “I was looking at the wrecked car and Joe Grimaldi [Shierson’s partner] came up and put his arm around me and said, ‘I know just the guys who are gonna buy this car’ and proceeded to make us a deal to buy the wreck. I think I paid $3000 or $5000 for the wrecked rolling chassis.”

Norman and his crew at Norman Racing Group in Berkeley rebuilt the car, which Norman and teammate Dan Marvin campaigned as a two-car team in 1977 and 1978 in both SCCA Club and Pro races. However, when Atlantic eventually shifted to ground-effect cars in the early 1980s, the March became just another old racecar, so Norman sold it off to original Ecurie Canada team mechanic Graham Scott, who intended to restore it back to its Villeneuve-era configuration. However, the car languished for eight years until Norman repurchased it in 1988. At that point, it sat in his shop for the next 16 years until it was announced in 2004 that a newly formed historic Formula Atlantic group was going to race at Trois-Riviéres. This was the final impetus that Norman and Marvin needed to return the car back to the shape it was in when Villeneuve stunned the racing world at Trois-Rivieres, in 1976.

Since it’s rebirth in ’04, Marvin and Norman have raced the March in numerous historic race meetings around the country, where the car has continued to be a dominating player, even 30 years on, and oftentimes against much bigger machinery.

Driving a Fantasy

Photo: Jim Williams

I arrived at Infineon Raceway (nee Sears Point) on a cold, blustery Saturday when Northern California’s CSRG was holding its big season kick-off, honoring Alfa Romeo (see this month’s Photo Gallery). CSRG had generously offered to allow me the use of the track at lunch to test Norman’s March. While my adolescent fantasies usually revolved around Villeneuve’s Ferrari 312T4, the prospect of driving his all-conquering Atlantic ride was both exciting and a bit daunting. Why daunting you might ask? The trouble is this car races all the time with the unbelievably quick Dan Marvin behind the wheel. Dan raced Atlantic cars against Villeneuve in the day (and even outqualified Gilles in his debut race!) and has raced this car both in period and now in historic racing. People are used to seeing this car fly when it is on track! So it’s a fine line for me to dance, because on the one hand I want to drive fast enough that I don’t look like a total wanker, and on the other I don’t want to drive over my head and do something stupid. This isn’t the way I envisioned this unfolding when I was lying in bed 30 years ago!

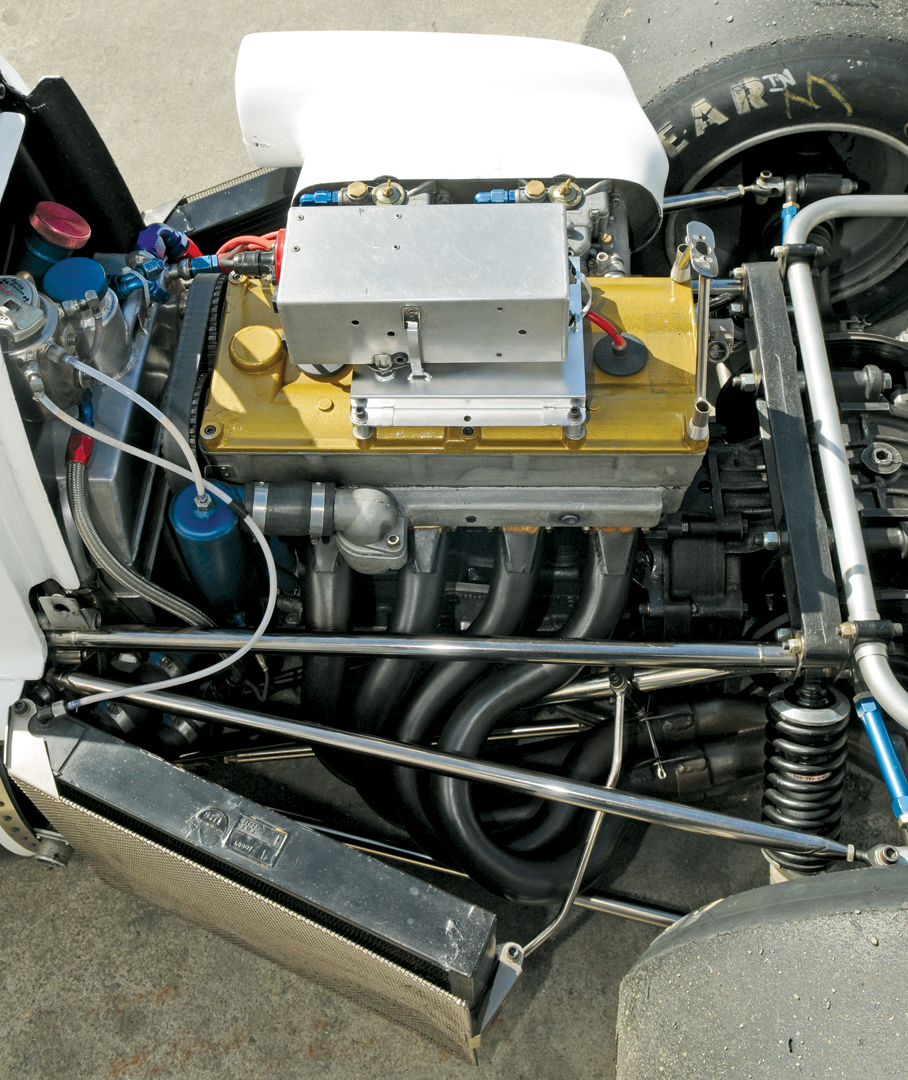

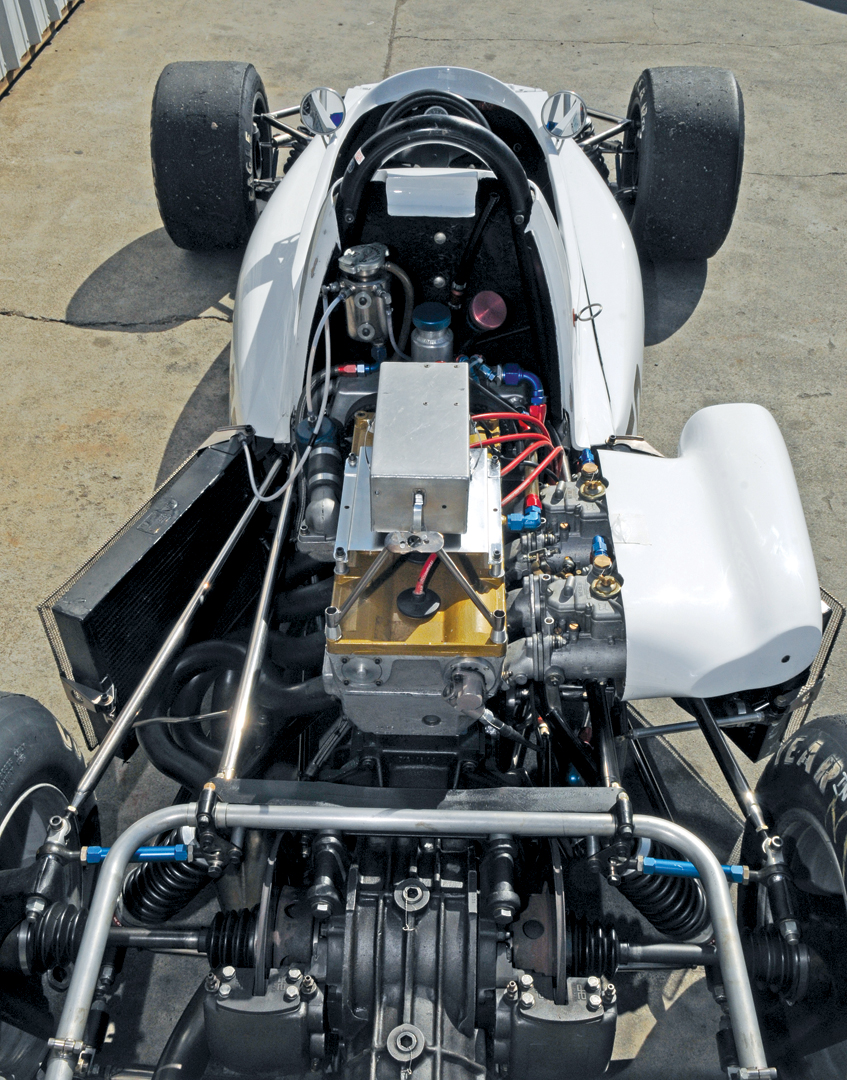

As I slide down into the upholstered plastic seat, the car swallows me whole like an oyster shooter. Is it my imagination or does this car fit me perfectly! The high-sided cockpit is remarkably comfortable both in terms of seating position and room to work. As with literally all single-seaters of this era, the cockpit is minimalism raised to an art form—small diameter steering wheel, center-mounted tach, oil gauge to the left, temperature gauge to the right and short and stubby shift lever that falls right to hand. After being strapped in, I flick on the ignition switch, make sure the Hewland is in neutral and give the starter button a jab…blattt!…the 1600-cc Cosworth BDD, undoubtedly the winningest engine of all time, fires obediently to life.

Having raced a Ralt RT-1 for some time, sitting in the March feels like coming home. With a newfound sense of confidence, I dip the heavy clutch pedal, pull the shift lever back and over for first gear, give it a gentle squeeze of gas and gently pull out down the pit lane. (I was pleased to learn later that one wag on the pit lane had commented that they were surprised that I didn’t stall it, like everyone else does!)

As I dodge and weave around our camera car for a lap or two, I can’t get over how right this car feels! It is solid, as if it were carved from a single billet of aluminum. There are no rattles or creaks, the steering is razor sharp and the throttle response almost telepathic. Now, March production racecars were somewhat notorious in the day, for having, how shall I put it, varying build quality, so I know a lot of this particular car’s character can be attributed to the exacting reskinning and full restoration that Norman and company have lavished on this particular example. In any case, the car felt superb and I hadn’t even gotten out of second gear yet!

Photo: Jim Williams

After two slow laps following the camera car, I’m chomping at the bit to see what the Villeneuve car will do. As the camera car pulls off into the Infineon pit lane I make a quick stab of the throttle for the Turn 11 hairpin. Hitting the apex, I squeeze on the gas and start rocketing up the front straight. A quick lift and I snatch third gear and go back hard on the throttle, the BDD is howling behind my head as I lift for another quick shift up into fourth as I exit the left-hand dogleg along the front straight they call Turn 12.

Turn 1, is a left-hand bend that transitions uphill toward Turn 2. The March devours this turn like it’s not even there and launches up the hill so quickly, I momentarily have to reset my depth perception. With the hill adding a little extra braking force (not that the car needs it), I quickly drop down two gears to go cautiously through the blind, off-camber Turn 2. Once over the brow, the March gently slides a little outside, but the moment I roll back on the gas, the butt end hunkers down and the car is chewing up the tarmac on its way to Turn 3.

Turns 3 and 3A are a quick flick, left to right uphill, followed by a short blast in third gear slightly downhill to Turn 4. Approaching 4, I get a good opportunity to jam hard on the brakes, which per M. Villeneuve’s insistence utilized 4-pot Lockheeds front and rear, as opposed to the commonly used 2-pot on the rears of other Marches. In a car this light (1050-lb), the 4-pots run the risk of launching my eyeballs through the front of my helmet. Needless to say, they are strong, firm and more than adequate for the job. Powering out of Turn 4, I get a good burst of pure, adrenal-gland-tickling acceleration before I lift for Turn 5 and then get back on the gas for, what is to me at least, the most difficult turn at Infineon, The Carousel, Turn 6.

Photo: Jim Williams

The approach to Turn 6 is uphill and totally blind. As you crest the top, you have to remember that the track goes left and starts a long, steep, downhill twist that really loads up the right side of the car if you’re on it. The tricky part, again for me, is the need to upshift about two-thirds of the way down the hill, while you have the right side of the car so heavily loaded. Botch that shift, and the weight transfer will have you backwards and careening toward the outside concrete wall faster than you can think, “Oh poopey!”

Once I’ve negotiated Turn 6, I’m hard on the gas on the back straight. Out of the turn in third, it was foot to the floor, quick snatch to fourth, foot back to the floor, hard snatch to fifth and another blissful squeeze to the floor as the March absolutely rockets toward the Turn 7 braking zone. The sensation is like someone turning up the valve on your narcotic drip, you really, really want to make it last a few seconds more. After a few fleeting glimpses of nirvana, it is hard on the brakes and a quick succession of downshifts and throttle blips back down to second gear for the pair of right-handers that lead back to the esses. Again, here the preparation this particular car has received shines through as the Hewland FT200 gearbox is about the most buttery smooth I’ve ever experienced, but I’ll save what few superlatives I have left for the end.

Infineon’s Esses (Turns 8-10) are deceptively tricky in that you are constantly accelerating through them, which if you’re not very careful and very precise have a tendency to throw you offline by the time you get to the last turn or two, which by that point are at something just shy of warp speed. However, the March felt glued to the road as it smoothly devoured each successive turn. Launching out of the final turn and onto the short chute that takes you back to Turn 11, I’m flying in fourth gear, though I’m sure Marvin is probably flat out in fifth at this point! However, discretion is the better part of valor! Finally, I get another immensely satisfying sequence of downshifts and blips to take me back to second gear and the start of another lap.

What is scary about this car is how comfortable I felt in it from the moment I pulled out. With each successive lap I was charging turns deeper, holding onto the accelerator a little bit longer and all the while the car communicates nothing but solid, “Oh, you can go faster through there,” feedback. In short, it is absolute magic to drive, not just because Villeneuve launched his career and dominated the 1976 Atlantic season with this very car, but because it is simply an amazingly easy car to drive very, very fast.

Now the only thing left for me to make my childhood fantasy complete is to sample Villeneuve’s Ferrari 312 T4…please?

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis: Aluminum monocoque, with rear tubular subframe.

Wheelbase: 97 inches

Front Track: 51 inches

Rear Track: 51 inches

Weight: 1050 lbs

Suspension: Front: Independent with unequal length wishbones with coilover shocks and adjustable anti-roll bar. Rear: Independent with unequal length control rods, coilover shocks and adjustable anti-roll bar.

Engine: 1600-cc, 4-cylinder, Cosworth BDD

Carburetion: Twin Weber DCOE

Transmission: Hewland FT200 5-speed

Brakes: Lockheed 4-piston disc, front & rear

Wheels: 13 x10 front, 13×14 rear

Resources

The author would like to thank the kind generosity of Tom Franges and CSRG for accommodating this test drive. Likewise, we would like to thank Jon Norman and Dan Marvin for their trust and support in letting us test drive this special racecar.

Donaldson, Gerald

Gilles Villeneuve, The life of the legendary driver

MRP, Ltd, Croydon, UK, 1989

ISBN 0-947981-44-6

Lawrence, Mike

March, The rise and fall of a motor racing legend

The Amadeus Press, Cleckheaton, UK, 1989

ISBN 1899870547

Zimmermann, John

Year Zero

Motor Sport, October 2005

Halsmer, J. Peter

March 76B

Formula, March 1976