Formula One, by its very definition, is often seen as the pinnacle of motorsports. This holds true in many aspects, especially in the fact that the circuits that the cars race are some of the best in the world. Many tracks have been on the calendar for decades, and are world renowned, such as Spa-Francorchamps, which shares its status as a mecca of speed with the Temple of Speed, aka Monza. There are other tracks that have been built and certified by the FIA to Grade 1 status, which is needed for Formula One to race there.

Yet, through economics, mismanagement, or simply bad timing, many tracks have come and gone throughout the decades of the world championship. Some were dropped for safety reasons, such as the “Green Hell” that is the Nurburgring Nordschleife, or the old Kyalami circuit in South Africa, which saw multiple injuries and even a fatality occur on its slithery, snaking tarmac. Others, however, have simply been forgotten, lost to the annals of time and rarely, if ever, talked about, even amongst F1 enthusiasts.

Today, then, we shall look back at four recent tracks, all within the last 20 years, that time has already seemed to have forgotten.

Abandoned: Valencia Grand Prix Street Circuit, Spain

There was one race on the Formula One calendar that could be run on any circuit within continental Europe. That race, naturally, was the European Grand Prix, which has been hosted at various tracks such as the Nurburgring Grand Prix circuit in Germany, the Jerez Circuit in Spain, Donington Park Circuit in the UK, and all the way back when it was first run in 1983, at the famous Brands Hatch circuit in the UK.

In the mid-2000s, however, Valmor Sport Group, an entity headed by former motorcycle champion Jorge Martinez and billionaire owner of Villarreal Club de Futbol Fernando Roig, lobbied successfully to have the European Grand Prix moved from its current home at the Nurburgring to a new, specially designed and built street circuit in the city of Valencia. This, despite F1 CEO Bernie Ecclestone stating that no country should host more than one grand prix in a season. It became official when a deal was signed between the FIA, Formula One Corporation, and Valmor Sport Group on June 1, 2007, with the first race to occur the next season.

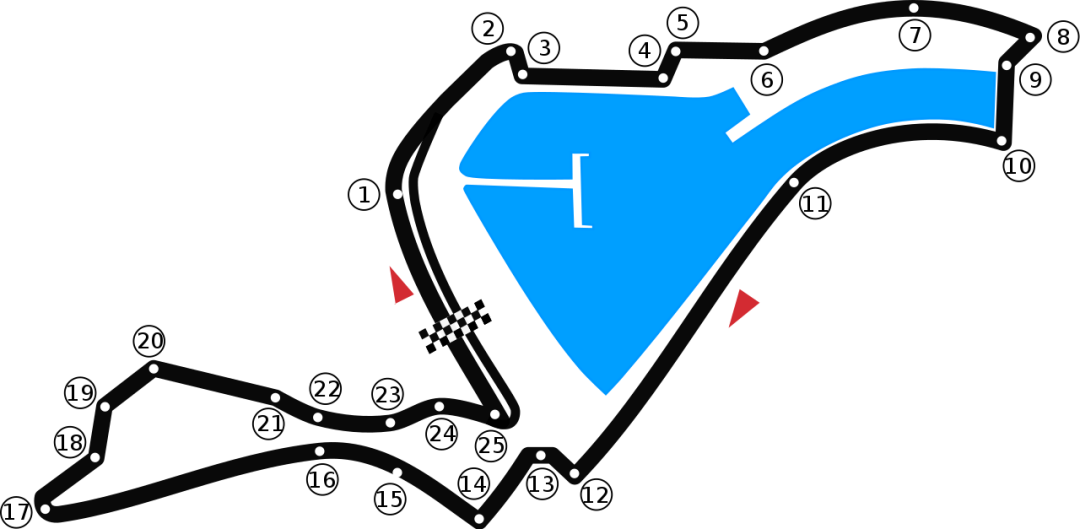

For most new tracks, it takes a few years after the deal has been reached to build the track itself, yet by using a lot of already existing city streets, the special portions of the Valencia circuit that needed to be built were able to be completed at a breakneck pace. The only part that really needed to be built specially to handle Formula One was the section that ran down to the turn 17 hairpin and its return to the marina area where the start/finish straight was located. The track was officially opened and used for the first time just over a year after the deal had been signed, hosting the Spanish Formula 3 and International GT Open races on the last weekend of July 2008.

At a length of 5.419 km (3.367 miles), it was a relatively short track, despite the cars hitting 200-205 MPH down the back straight. It had 25 turns in that distance, making it a very technical track, with 11 left hand corners and 14 right handers. Despite being wider and less technical than the other famous street circuit on the calendar at the time, Monaco, during the first European Grand Prix hosted there in August 2008, it was criticized for not having many passing opportunities.

The crux of this was that the straights were not really straight, and the corners, despite the width of the track, were very slippery off the racing line due to fine dust and sand brought onto the surface from the beach that was adjacent to the marina. This was also compounded that for the television audience, at least, the racing was processional and “boring.” In fact, the Valencia circuit, along with the complaints of boring racing, sped up the introduction of DRS into the sport, to add more excitement and overtaking on tight, twisting circuits.

The race highlights from the last year of Valencia, 2012

That isn’t to say that there weren’t a few epic or controversial moments that occurred in Valencia. One of the few times in the past decade a car has been launched completely airborne and flipped in the air happened in 2010, when Red Bull Racing’s Mark Webber moved to pass Lotus’ Heikki Kovaleinen, ducking to the inside after slipstreaming down the back straight. Kovalainen, however, braked before Webber expected it, as the RB6 F1 car was renowned for its monstrous brakes, and before he could react, he was looking straight up at the sky and then at the tarmac. Thankfully, the roll hoop did its job, the car rolled back onto its wheels from the inertia, and the tire barriers took the brunt of the impact when he hit the wall.

Valencia was also the site of one of the most emotional, powerful victories by Fernando Alonso in 2012, when he was driving for Scuderia Ferrari F1. There has been a rule in the FIA regulations from 2013 onwards stipulating that if a driver gets out of their car at any point during the in-lap after the checkered flag, they are considered to have abandoned their car and disqualified. This was implemented because of the celebration that Alonso did, getting out of his car, standing on the safety cell, and celebrating his win with the packed Spanish fans.

However, after the 2012 race, while negotiating a new deal to move the European Grand Prix back to Germany and alternate the Spanish Grand Prix every other year between the Barcelona-Catalunya circuit and Valencia, talks broke down. Formula One wanted just one race, consistently, at one track in Spain, while Valmor Sport Group, who had put several hundreds of millions into the track and the maintenance needed to keep it at FIA Grade 1 condition, wanted to make sure their investment was not in vain.

In the end, Barcelona-Catalunya, as a bespoke, well-known track that also hosts MotoGP, International GT, Spanish Formula 4 and Formula 3, won out over the Valencia circuit, which, being a street circuit, was realistically viable for only one week per year. In the end, after those hundreds of millions of dollars and five seasons on the F1 calendar, for 2013 the track was quietly shuffled off to the side and, after the FIA then removed the Grade 1 classification from the circuit, Valmor Sport Group abandoned the upkeep and maintenance needed to keep it pristine, and walled off the specially built sections.

The repercussions reached beyond Spain too, as Germany, which was set to see the return of the European Grand Prix to the Nurburgring, instead had to choose between having the German Grand Prix at Hockenheim, or the European Grand Prix. They chose to keep the German Grand Prix, so the European Grand Prix was shelved in name, only emerging again once in 2016 for the first race in Azerbaijan before it became the Baku Grand Prix.

You can still find the abandoned track sections in Valencia today, as the land has never been reclaimed by any developments, so nature has started to take over. It is run down, the tarmac is cracked and falling apart, and if you know where to look, you can still find the anchor points for the grandstands, which were removed and sold off as scrap. As to Valmor Sport Group, somewhere between 2012 and 2022, it too seems to have been quietly shuffled aside, although the two co-founders are still in business together with other ventures.

Reduced Then Quietly Removed: The Hockenheimring, Germany

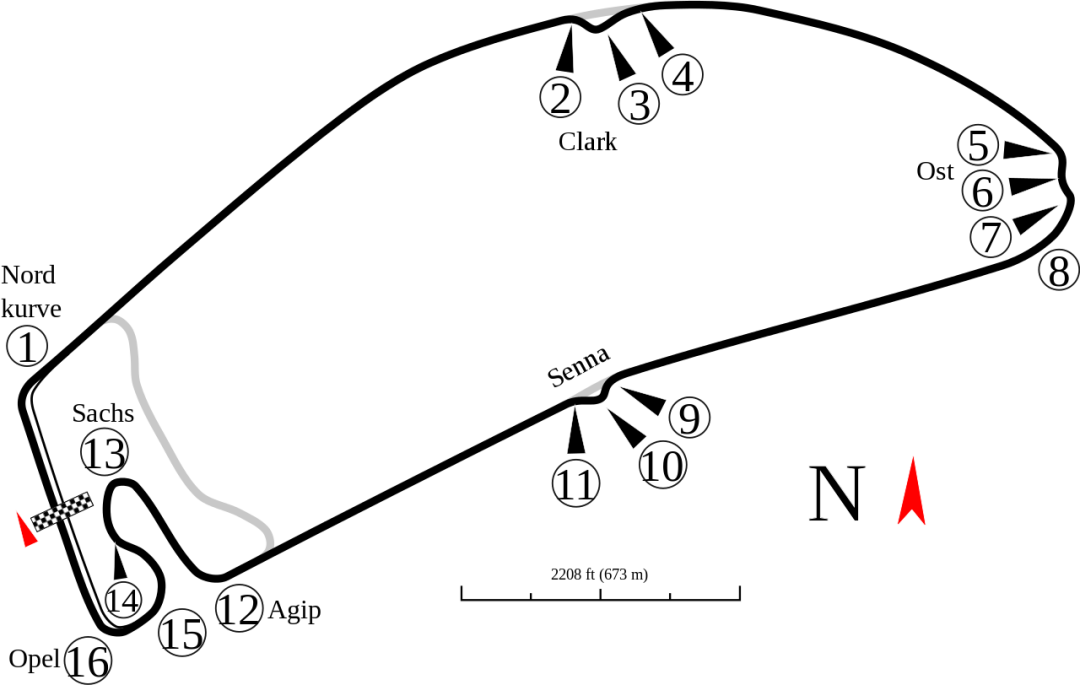

You can tell when someone started to watch Formula One by asking them which version of the Hockenheimring they watched the cars scream around. If they started in the V10 and V8 era, they watched the racing take place on the short, 4.574 km (2.842 mile) version of the track. If they had started watching during the days of Senna, Prost, Schumacher, Hakkinen, and Jacques Villeneuve, they would have watched the racing on the epic, 6.823 km (4.240 mile) “car killer” version, which called the current circuit the “arena section.”

The “Alt Hockenheimring” (literally, “Old Hockenheim”) was so large, in fact, that like with Spa-Francorchamps today, you could have varying weather across the entire circuit. It gained the reputation as a car killer, however, because it was brutally hard to set up a car for. There were kilometer long straights that needed the cars to be as low downforce as possible to max out their top speed, but there needed to be enough downforce produced to maneuver around the three chicanes in the forest section, and the tight and technical arena turns.

One thing that Old Hockenheim produced in spades was drama. Looking at the track layout above, it may seem to be quite simple, but the reality is that with those huge straights, slipstreaming allowed for last minute dive bombs in the braking zones. More than once, the risk was rewarded with a fairly dramatic crash, while other times, some of the greatest passes of the year happened when a driver that could balance their brakes right on the verge of locking took the chance.

The track also earned the name of car killer because of the fact that for 90% or more of the lap, the engines were howling away at the 18,000 RPM rev limiter in 6th gear as the car tore down the straights. Ever the fickle pieces of machinery, if an engine lost even a small amount of cooling, or blew a tiny gasket somewhere, that was it, the engine blew up in a big cloud of white smoke chugging out of the exhausts as the driver pulled off the circuit.

Michael Schumacher during qualifying in the last year of the Old Hockenheimring, 2001

However, there were a few glaring issues about the track, least of which was its size and location. Buried deep in the Baden-Württemberg forest, there are only a few grandstands at the far end of the track around the second chicane, with many more grandstands in the tight, twisty arena section. For a good 60% of the lap, then, no one except the marshals, the TV crews, and the drivers themselves saw much of what happened in the forest.

Also, due to the need to balance the car between speed and grip, cars would approach the forest chicanes at near maximum speed, and even the slightest error could cause devastating crashes. It was simply too fast, too big, and too scary for the FIA to continue racing there, and they revoked the certification of the track, effective after the 2001 German Grand Prix until and unless the track was reprofiled to a short circuit. That reprofiling was completed in time for the 2002 season, and the German Grand Prix was once again held at the “New” Hockenheimring.

As to the old forest section? After it was walled off by the new track profile, and having grandstands installed where the first straight passed through, the track was simply left to the passage of time. In the past two decades, while you can still see the gap through the trees, the track surface has been almost completely overgrown and replaced with nature. You can do a hike around it, but the interest in Hockenheim as a whole has diminished.

That last fact is because after the 2019 Formula One season, under F1’s new owners Liberty Media, no new deal was signed to continue racing there. It was quietly removed from the calendar, and has not returned since, leaving no Formula One race in Germany whatsover. However, the track itself is still used by the German DTM championship, and multiple Porsche Carrera Cup and ADAC GT Open races still happen there, as it still holds an FIA Grade 1 certification. It’s not abandoned, as Valencia was, it’s just now a local German track for German race series, and a quite popular one at that.

Unfortunate: The Korean International Grand Prix Circuit

Formula One Management, the company owned by Bernie Ecclestone, was looking to leverage the growing interest in the sport in mainland Asia during the start of the new century. They found two interested nations with the finances to be able to build and maintain a Grade 1 classification facility in China and South Korea. After working out the finer details, it was announced on October 2, 2006, that starting from 2010, South Korea would host Formula One as the to-be-built Korean International Grand Prix Circuit in Yeongam, a city along the Southern coast of the nation.

Part of the deal that was signed was that the circuit would have 7 seasons worth of races, with an option to extend it by 5 more, taking it to 2021. However, when the provisional season schedule for 2010 was released in the latter half of 2009, Korea was listed as tentative for October 17, 2010, later in the season than expected by many. The reason for this was that the track was still under construction, with the organizers and management of the track itself confirming in December 2009 that they were on schedule for their expected July 2010 completion date.

There were a few kinks in the hose, however, as the grandstands were taking longer than expected to complete, as well as the VIP accommodations for both spectators and teams alike being behind schedule. As such, July 2010 arrived and while the circuit tarmac itself was laid and ready, most of the grandstands, the hospitality buildings, media center, and the like were not completed. The reason was that the rainy season on South Korea’s coast had nearly twice the rainfall expected, which led to soil degradation that made it exceedingly difficult to build large, weight bearing structures. The FIA wanted to send their inspectors as soon as viable to certify the circuit to Grade 1, and to give the organizers time to finish the circuit, the race was pushed back one week to October 24.

Summer passed, and the circuit was still not fully completed, and as September 2010 rolled around, most of the buildings and grandstands had been built to spec, but there were still appliances, wiring, and the like to be installed. Finally, on October 11, 2010, the FIA was able to inspect the completed track, a scant 13 days before the race was scheduled to take place. Charlie Whiting, Race Director and man who literally had the final say on each Grand Prix taking place, confirmed on October 12 that the race would go ahead.

Unfortunately, while the race itself was a roaring success with packed grandstands and action on every lap, the scheduling overruns had racked up quite the bill, and the fee imposed by Formula One Management to sanction the event, agreed upon four years before, put severe strain on the organizers. While they were able to pay it, they expressed dissatisfaction over the steep price. Ecclestone fired back that the organizers had been aware of the costs for four years prior, and was not willing to renegotiate the terms that the Korean organizers had signed to.

Sebastian Vettel’s pole lap during qualifying at the last Korean Grand Prix in 2013

The back-and-forth continued throughout 2011, with the race still taking place, but under the shadow of a threat that it would be removed from 2012 if the organizers were not able to pay the sanctioning fee. After the season opening round in Australia, both Formula One Management and the Korean organizers announced that they had reached a new deal that would cut costs by a staggering $20.5 million for the race weekend. However, Kang Hyo-seok, the director and CEO of the Korean organizing committee, openly stated that they were still expecting to be in the red by $26 million for the race weekend, despite hosting other races throughout the year.

The race still went ahead in 2012 and 2013, with net losses for both years combined totalling just over $55 million USD, with 2013 being the more devastating of the two years as there were visible gaps in the crowds at the grandstands, some of them even appearing half empty. As it stood in December 2013, the organizing committee was barely hanging on by a thread, able to keep the circuit in Grade 1 condition by the tightest of margins. A preliminary date was provided for 2014, but the final calendar, released in the first few weeks of 2014, saw the Korean Grand Prix removed. At the end of the year, Bernie Ecclestone released the tentative 2015 calendar, with Korea still listed, but he openly stated that it was on there for contractual reasons only.

Halfway through the 2015 season, the organizing committee informed the FIA that they would not be able to host the grand prix, citing extraordinary costs that would probably bankrupt the circuit. There were plans to honor the original contract and host a last race in 2016, but those plans never came to fruition as the circuit did not pay the sanctioning fees for the third year in a row. As such, with the original contract terms completed, the race was removed from any future plans for F1.

The truly unfortunate part of the whole Korean saga was that it was a track that the drivers enjoyed, had excellent sightlines for all the grandstands, and was wildly popular with the South Korean fans, who sold out the race all four years it ran. However, the long construction time had led to cost overruns in the tens of millions, and without a way to recoup the money that had been shifted from the budget for the FOM fees, the race simply sputtered out when the choices were bankruptcy and liquidating the track, or keeping the circuit without having Formula One race there anymore.

Today, the track is still used for most of the year for local races, including the Asian Touring Car Championship, the South Korean Superrace Stock Car Championship, Korea Speed Racing, and is an on-again-off-again circuit used for the Porsche Carrera Cup Asia and the International GT Asian Championship. It still maintains an FIA Grade 1 certification, and is finally making money each year, but will likely never see another Formula One car turn a wheel in anger on its tarmac.

Politics: The French Grand Prix At Magny-Cours

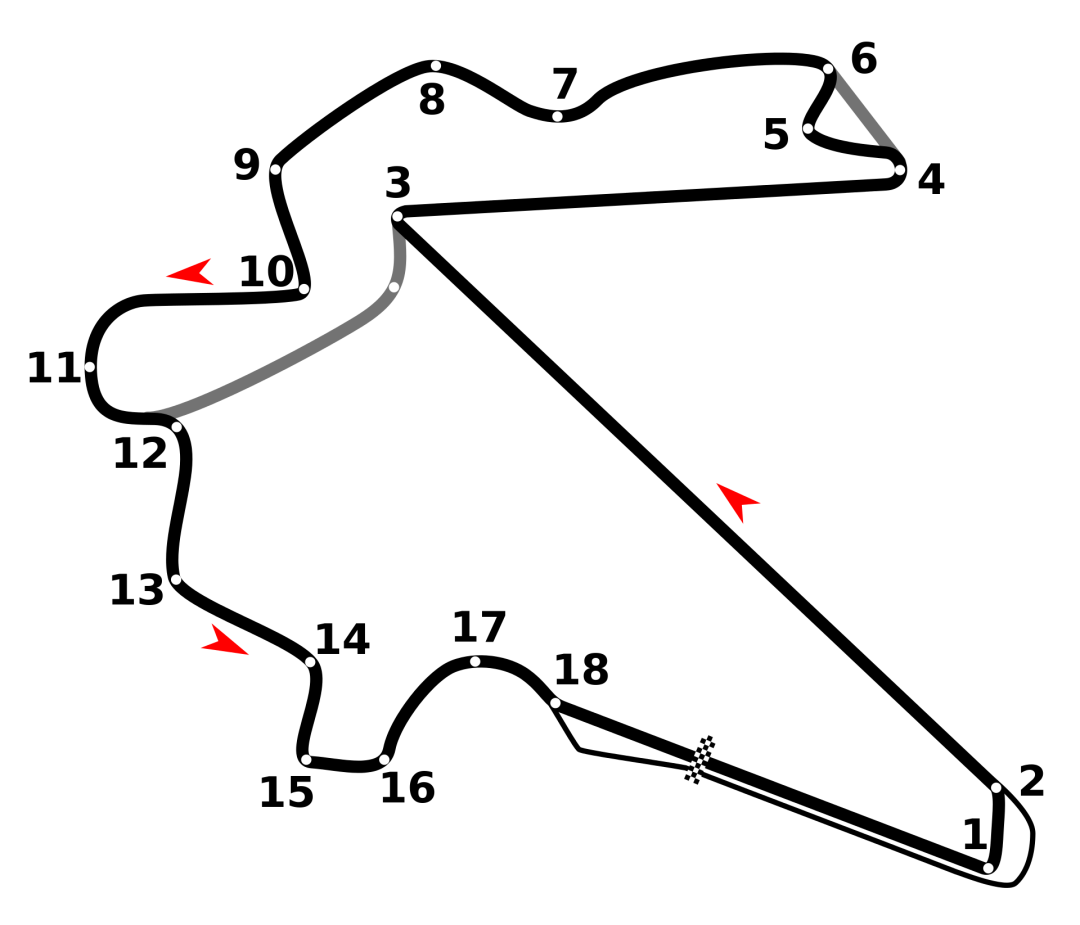

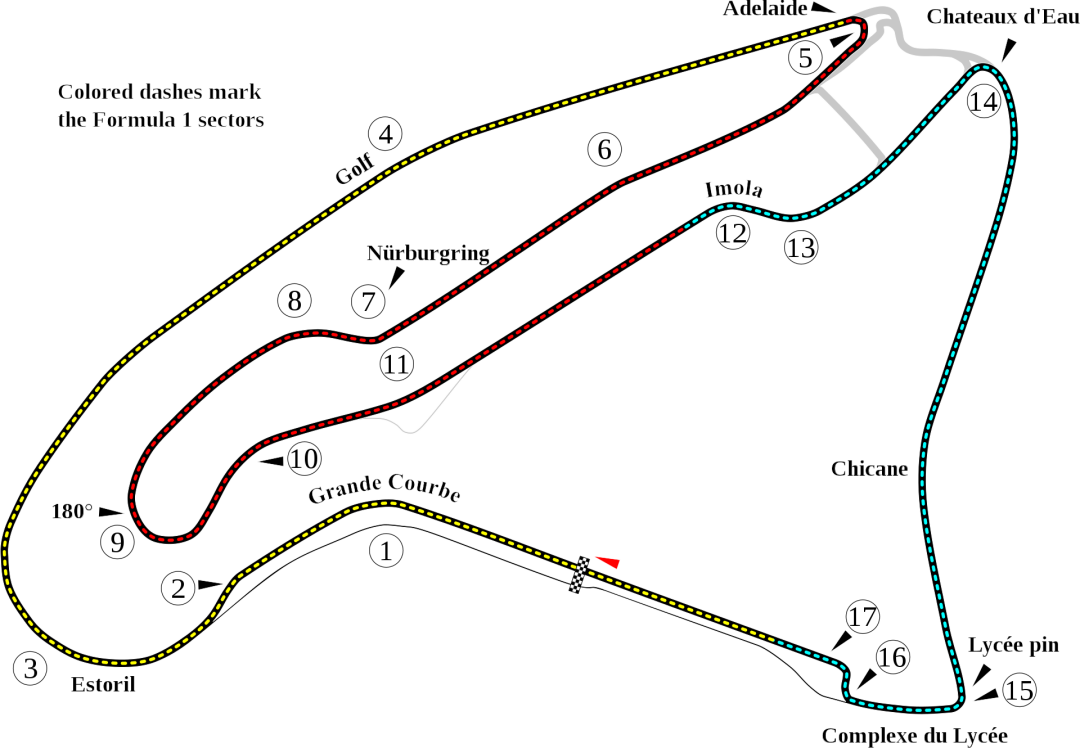

Also known as the Circuit de Nevers Magny-Cours, anyone that watched Formula One between 1991 and 2008 knows of this extremely fast, technical track that doubles back on itself halfway through the lap. While the racing that occurred on its legendary tarmac was fast, tight, and often exciting, many in Formula One did not like the track for one specific reason: It is smack dab in the middle of nowhere.

Set between the major cities of Paris and Lyon, the towns of Nevers and Magny-Cours are not even on the main expressway system, instead located at the midpoint of a tertiary highway that was difficult to get to with large trucks carrying the cars, spare parts, garage setups, and the like. However, the organizers of the French Grand Prix moved the race there in 1991 away from Le Castellet, home of Circuit Paul Ricard, to stimulate the local economy and make the quaint little townships a tourist destination.

At first, the plan succeeded, and the last decade of the 20th century saw the French flock to the track to watch several legendary races. National hero Alain Prost won at Magny-Cours in 1993, the last time a French driver won a French Grand Prix. It saw the mid-season battles in 1998 and 1999 between Mika Hakkinen and Michael Schumacher jousting with each other down the long, flowing straights and through the tight corners. It also saw Schumacher set the record for the fastest any driver has secured a world championship, after only 11 rounds, the 11th taking place at Magny-Cours.

Fernando Alonso in his Renault years, showing just how fast and flowing Magny-Cours was, and why it was a fan favorite with the drivers needing absolutely pinpoint precision and a hefty sense of courage to brake as late as possible after huge straights.

The track was also the home base for the Ligier F1 Team, before it was bought by Alain Prost and became Prost F1. Both versions of the team did much of their pre-season testing at the track, as it has a combination of long straights and tight corners that reflected a lot of the circuits in use at the time.

However, by 2004, the interest in the track started to wane, as it was still a long drive away from the major expressways. The local economy suffered slightly, but the track itself started to tread water, keeping afloat through hosting extra races and events throughout the year. The same happened in 2005, which saw the schedule of races for the year expand, with races being held in neighboring countries such as Germany and Spain that were more accessible.

2007, however, was when the politics of Formula One, often whispered about but never truly discussed openly at the time, reared its ugly head. The FFSA, the organizers of the French Grand Prix, said that the race for 2007 had been funded, but that the 2008 race was on an indefinite “pause,” due to the financial situation and ever increasing fees needing to be paid to be sanctioned by Formula One to have a race at the circuit.

Bernie Ecclestone and Formula One Management fired back that the 2007 race was going to be the last time Magny-Cours hosted the French Grand Prix, because the track was “buried deep in the wood” and not easily accessible for the majority of teams and fans. In a bit of counterpoint, the FFSA was able to generate enough revenue to pay the sanctioning fee for 2008, in essence rubbing Ecclestone’s statement in his face, to the point that he met with the French Prime Minister to see if the race could be secured by the government for 2008 and 2009.

While there was an agreement in place where the French government would subsidize the 2009 race, it was ultimately canceled in October of 2008, as part of the deal was that the track would generate most of the sanctioning fee, with the government helping with facility costs and subsidizing part of the sanctioning fee. To keep FOM’s interest, the FFSA announced that it would reprofile the circuit into a “Magny-Cours 2.0,” but after repeated attempts to get things moving, that too was ultimately canceled after the budget for the circuit had no way to support it and pay the now extremely expensive sanctioning fee that was in the tens of millions of dollars.

Ultimately, the FFSA broke with the management of Circuit de Nevers Magny-Cours, looking to secure another track to host the 2010 French Grand Prix. However, with his face still sore from the having the 2008 race rubbed in his face, Bernie Ecclestone did not reach an agreement with the FFSA to have a 2010 French Grand Prix. It was not because he was spiteful or an evil man, it stemmed from the fact that the FFSA and the Circuit had both struggled for years to secure funding for the sanctioning fee, while other nations and tracks were literally waving millions of dollars in the air to get his attention.

The French Grand Prix did not run for nearly a decade, until a new deal was inked between FOM and the FFSA in 2015 for the race to return to its “home,” Circuit Paul Ricard at Le Castellet. While the track is well known for its hundreds of layouts, as well as being the proving ground for hundreds of race cars each year during their development cycles, the complaint from fans this time is that the race is relatively boring and processional. Nothing like the fast, tight racing that took place on the black stuff at Magny-Cours, yet, that bridge was burned and it is very unlikely that Formula One will ever return to the little sleepy towns of Nevers and Magny-Cours.

In a twist of irony, however, Magny-Cours is used by a lot of race teams to iron out the bugs in their cars, as it is less expensive to rent the track there than it is to rent Circuit Paul Ricard. As well, the circuit hosts a round of the French F4 Championship, a major race in the GT3 World Challenge Europe, as well as the Alpine Cup one-make series, and its highest profile race as host in September of each year of a round of the World SBK Championship, one of the top two tiers of motorcycle racing.