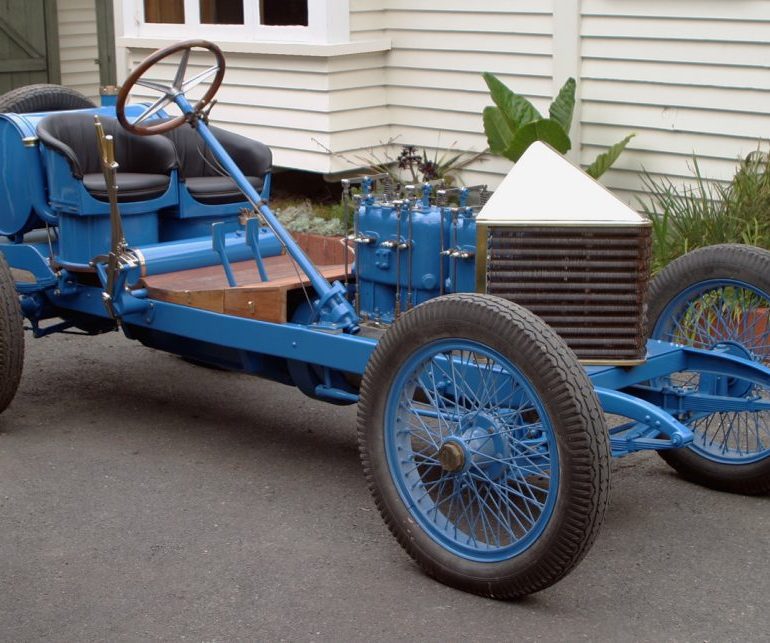

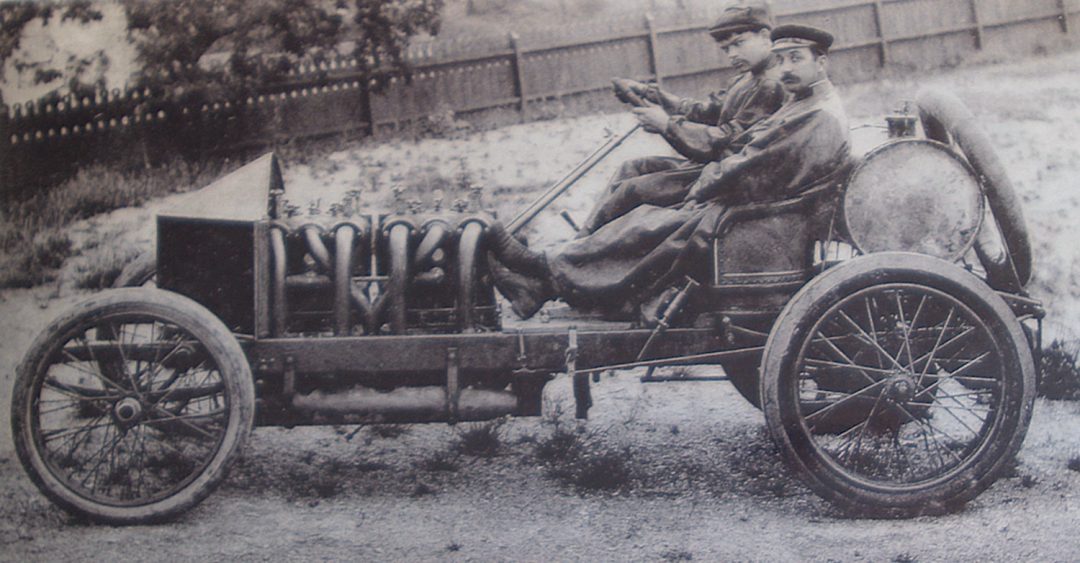

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]eeing the Darracq 120 racer that Louis Wagner (also a pioneer aviator) drove to victory in the 1906 Vanderbilt Cup race in Wallace McNair’s shed in Hamilton, New Zealand, felt a little like finding a Rembrandt at a garage sale. The car ranks up there with Ray Harroun’s Marmon Wasp, the first Indianapolis 500 winner, for historical significance.

Unlike Harroun’s Wasp though, which has been lovingly cared for at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Hall of Fame museum over many years, this historically pivotal machine wound up half a world away from its home in France and long forgotten. And sadly, so is the story of how the car got to New Zealand in the first place.

More often then not, a racecar that is a few years old is just regarded as obsolete, and relegated to a shed somewhere. They are generally not worth much, and they can’t be driven on the street, so no one cares until they age a bit, and their historical significance becomes more apparent.

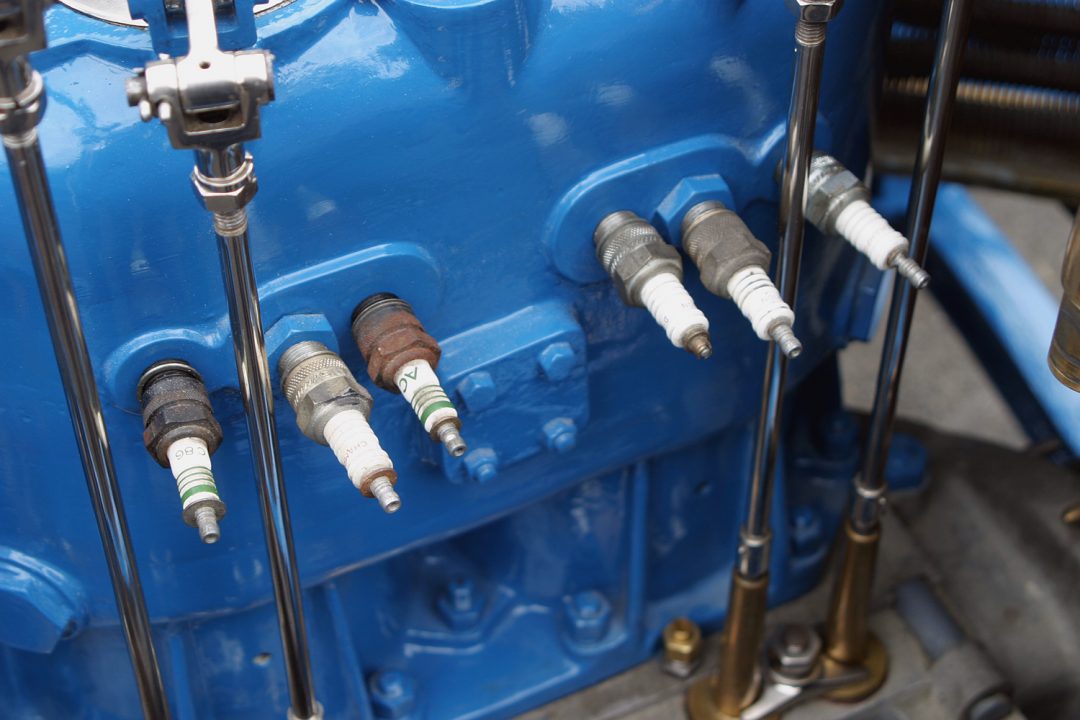

But in this case, if winning the Vanderbilt Cup weren’t enough to make the car important, another bit of information that is well documented makes the racer even more illustrious, and that is the fact that it was also land-speed-record-setter Sir Malcolm Campbell’s original Blue Bird! He named the machine after a play he had seen. Of course, the car’s French racing blue paint job may have been an inspiration too. It was Campbell who added the third sparkplug on each cylinder, no doubt to try to get a more complete burn out of the low octane fuel across the huge pistons of the machine.

You can see the third plugs on each cylinder in some of the photos I took back in 2004, but restorer Wallace McNair removed them later as you can see in more current pictures. And today the car has been modified in minor ways, such as the pan under the engine to collect the oil from its total loss system in order to make it usable on modern tracks, but in all but the most minor details it is as it came from the Darracq works originally.

This legendary Darracq also competed in the very first French Grand Prix, at Le Mans, on June 26-27, 1906. The rules stipulated that the car could weigh no more than 1,000 kilograms (2,200 pounds) plus a seven-kilogram allowance for magneto and dynamo. The event was run on a 64-mile circuit and consisted of six laps on each of two days. The Darracq was up against the likes of Fiat, Clement Bayard, Mercedes and Locomobile but had to retire with engine problems after two laps. That race was won by Ferenc Szisz in a Renault AK 90CV doing an average speed of 62.88 miles per hour.

Two years previous to the first French Grand Prix, in the United States, W. K. Vanderbilt II had established the Vanderbilt Cup race to promote the sport of automobile racing in America. Vanderbilt did this after he set a land speed record of 92.30 miles per hour, in 1904, in a Mercedes on the beach at Daytona. The Vanderbilt Cup race was run on Long Island over mostly unpaved public roads, so all the dust combined with the oil expelled from the primitive engines with their total loss oiling systems soon made for a slick, toxic gumbo in which the drivers had to compete.

And if that weren’t dangerous enough, crowds lined the raceway circuit without benefit of safety barriers, often creating hair-raising hazards as the racers thundered by. In fact, in the 1906 event, won by Louis Wagner in the Darracq, a spectator stumbled onto the course and was killed by one of the competitors. This tragic accident caused such a stir that the event was not held again until 1908, and it inspired Vanderbilt to devote himself to road safety in New York in later years.

The rules for the Vanderbilt Cup race were that drivers began at timed intervals, with the car doing the fastest time from start to finish being declared the winner. An astounding 250,000 fans attended the 1906 running of the race, which was America’s most prestigious automobile event at that time. (The Indianapolis Speedway didn’t hold its first race until 1908, with the first 500 mile event coming in 1911.)

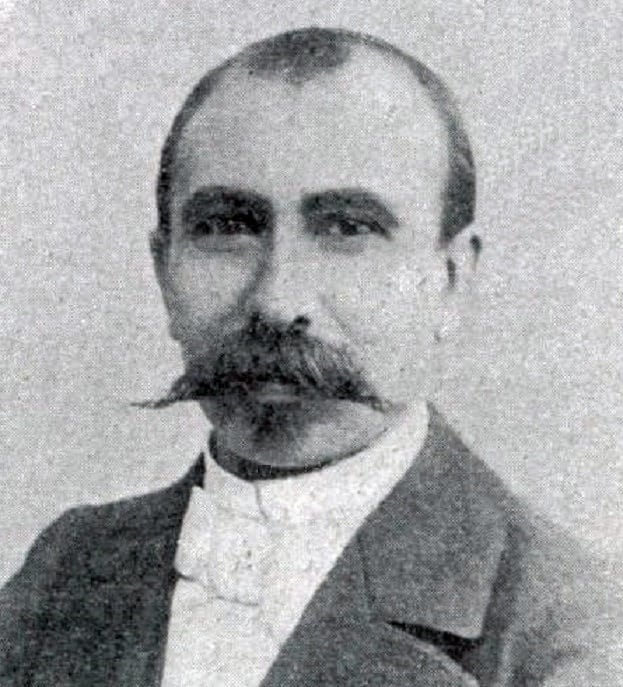

Here, in Louis Wagner’s own words, is how the event progressed:

“Starting in tenth place my time for the first lap, 28:36, enabled me to overtake and pass Nazzaro and Luttgen, then Heath and Le Blon, on the initial circuit, and Shepard at the tape. The leading cars were behaving with wonderful consistency. But the crowd! On rounding the Hairpin Turn for the second time, directly in the road were at least fifty persons as we approached the turn. They swiftly made way, but my car must have brushed at least a dozen coats while taking the turn. I actually shut my eyes and piloted the machine by blind instinct – expecting any moment to mow down several lives. That no one was slain was nothing less than a miracle. For the oil-sodden roadstead, to one traveling faster than a mile a minute, was nothing but a very narrow ribbon fringed at brief intervals with blotches of humanity. As for the eleven sharp bends in the course, it was impossible for me to know from my own vision just when and where they may be met. For this knowledge I depended entirely upon my companion who directed the way with his hand.

“As we swung into the stretch leading to the treacherous Bull’s Head Turn, and while going fully eighty miles an hour, one of the rear tires struck a broken glass bottle which had been thrown into the road and collapsed with a terrific detonation. My hopes collapsed with the tire. Some two miles farther on was our emergency station and, without slackening speed, though at the imminent risk of disaster, we got there. Every second was a century. Without realizing what I was doing I took a glass of champagne and two raw eggs, while the emergency crew wrestled in a frenzy with the tires.

“It seemed but a fraction of a moment before a vague speck appeared two miles away on the course. It swiftly became a cloud, then a dreaded outline, and with a sudden rush and roar. Lancia thundered by and was gone. There was no more stopping or slackening at turns, no further fear or concern over the reckless crowd. A mile from the finish it became evident that the dense mass of spectators was beyond control. Lancia had finished. But how long ago? As in a trance a bugle sounded and the next moment, with a flash and volley, the Darracq was over the tape – the winner.” from: “Early Adventures with the Automobile,” Eye Witness to History, www.eyewitnesstohistory.com (1997).

After 1906, all that is known for sure is that Sir Malcolm Campbell purchased the car in 1910 and raced it at Brooklands in England; but exactly how, when, and why it came to the Antipodes is lost to history. It is said that in 1914 an Irish immigrant New Zealander purchased the car, imported it, and took its engine out to use in a speedboat, but nobody knows for sure.

Sadly, The Great War intervened before he could complete his project. After World War I, the fellow’s widow offered the car and motor for sale, and another New Zealander who also intended to use the engine in a speedboat, purchased them in 1919. But in the end the motor out of the old racecar wound up powering a stand-by generator at a Christchurch newspaper while the chassis languished in a barn.

New Zealand, a century ago, was much as it is now, a picturesque and prosperous country demonstrably in love with cars, boats and speed. Keep in mind that over the years this little island nation of four million people has produced great champions such as Bruce McLaren, Denis Hulme and Chris Amon, as well as the young four-time Indy car champ, Scott Dixon (who we’ll also see has a relationship with this car).

Cars were imported to New Zealand as soon as they began producing them in Europe and the U. S., and a number of speed and hill climb meets were held in the country even before World War I. Road racing developed early, and cars and motorcycles were common even in those early days.

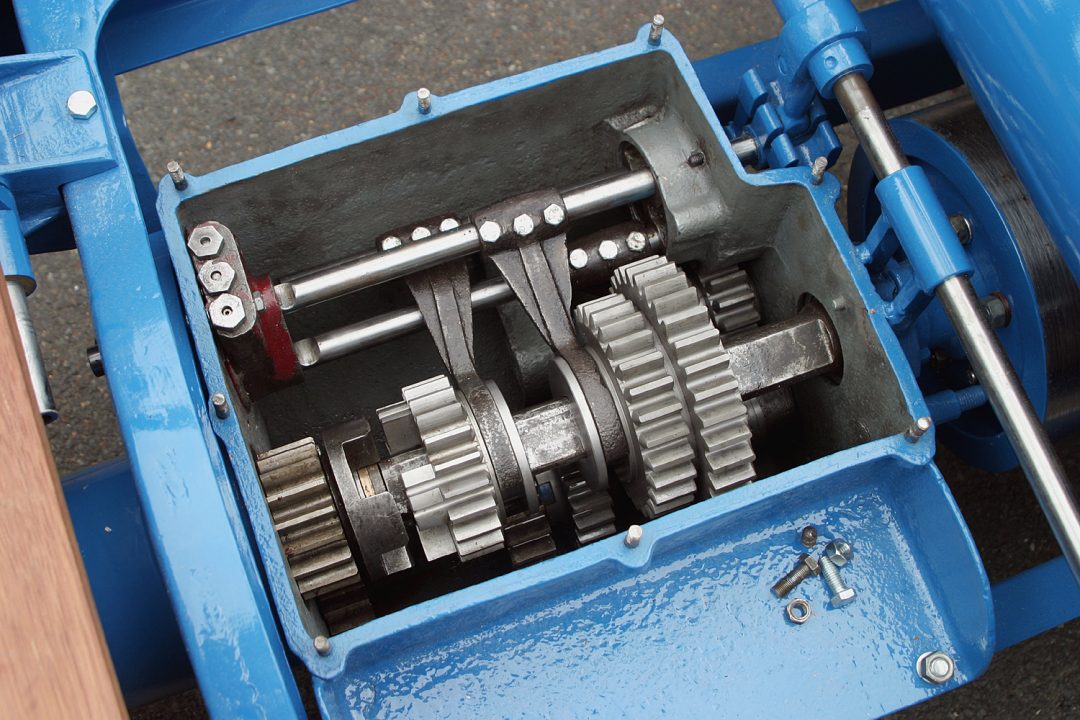

Though some of this car’s history is now lost, its pedigree is indisputable. A casual inspection would be enough to convince most of us. There is no mistaking that technologically advanced intake and exhaust system, that huge 14-liter, overhead valve, four cylinder engine with its cylinders cast in pairs, the swept back V-shaped radiator, and that monumental, remarkably advanced slider gear transmission.

When we first photographed the car in 2004, Wallace McNair had a few more details to attend to, such as hooking up the spark plug wires, before he was ready to light it off and experience the bark of this famous 100-year old racer. But after that, as soon as he was able to complete the car and do a few test runs, his wife began demonstrating it in historic races at major road courses in New Zealand, such as Pukekohe south of Auckland, and later, Hampton Downs.

Alexandre Darracq (1855 -1931) originally manufactured sewing machines in France. He then founded the Gladiator Cycle Company in 1891 and began making Millet motorcycles. These ventures paid off so handsomely that he went into the manufacture of automobiles in the 1890s. His first cars were electric, but as the internal combustion engine began proving itself more versatile, he switched to that form of propulsion.

Remarkably, even though Darracg himself never learned to drive, he founded one of the first schools for racing drivers. But then, in 1908, Darracqretired to the French Riviera where he invested in the Hotel Negresco in Nice. He died a wealthy man in 1931, some 20 years after his foray into auto manufacturing.

The company may now be all but forgotten, but Darracq was the most successful manufacturer of automobiles in 1904, producing 1,600 cars under the Darracq, Talbot-Darracq and Talbot trademarks, using mass production techniques well before Henry Ford’s merry-go-round got started. An early Darracq also set the world land speed record in 1904 at 104.52 miles per hour, eclipsing Vanderbilt’s brief brush with glory.

Then, in 1905, Victor Hemery upped the ante to 109.65 miles per hour in another Darracq. After that, in 1906, Louis Chevrolet built a Darracq 25-liter, V8-powered car in which Victor Demogeot, his mechanic, set a world land speed record of 122 mph.

Also in 1906—the same year as our feature car— Societa Anonima Italiana Darracq began building automobiles in Italy under license. The original factory was in Naples but the operation was later moved to Milan and its name was changed to Societa Anonima Lombarda Fabbrica Automobili or ALFA for short. This Italian branch of Darracq also built several race-winning cars in the early years. Then, in 1915, Nicola Romeo took over the company and dubbed it Alfa Romeo.

This 1906 Darracq Vanderbilt Cup winning car weighs less than the 2,200 pound limit for Grand Prix racers at the time, but produces 120 horsepower, so it is quite capable of speeds of over 100 miles per hour. Wagner won the 1906 Vanderbilt Cup race averaging 61.43 miles an hour— an incredible feat when you consider the conditions.

At the time I first noticed the ancient Darracq in McNair’s shed, I thought it was still incomplete because it was undergoing restoration. I assumed the cowl and hood were off the car temporarily, but I was wrong. The original machine actually had no cowl or hood. It was just as you see it in these photographs.

There were a few more details to be dealt with back then as you can see in some of the earlier photos, but McNair’s Darracq was essentially complete, and about as Spartan as any race car ever built. Even the driver’s seat does double duty in a sense, because it is perched on top of the water reservoir for the cooling system.

Driving such a car without even a toe board on which to prop your feet under braking must have been absolutely harrowing. But maybe the brakes didn’t matter much since all you had was a hand brake and tiny rear wheel mechanical binders that— given the combined footprint of the narrow tires— don’t look like they could even slowthe machine down from above 20 miles per hour.

The Darracq Grand Prix car also has a leather-faced cone clutch that is either engaged or disengaged. There is no feathering it. On the floorboard are just the conventional brake and clutch pedals. Tiny, bicycle-like levers attached to the steering column control the throttle and spark.

We were there for one of the inaugural shake-down spins around McNair’s neighborhood back in 2004, and when he started the engine, car alarms in the area went off, causing a a stir among the neighbors, even though they were fairly used to Wallace’s shenanigans because he also occasionally fires up a vintage Sunbeam land speed record car he also restored that is equipped with an immense World War I Handley Page bomber engine.

In more recent years, Anne Thomson— restorer Wallace McNair’s wife— has exhibition-raced the car in New Zealand. And during that time she took a fellow automotive journalist for a ride around the Hampton Downs road course. All he could say was that it was “Terrifying! There is no cowl, nor even a toe board, there are no seatbelts, and the seats are no more than tiny buckets.”

This ancient Darracq did 108 miles an hour when it was built, and was clocked at over 100 at a local track recently with Ms. Thomson at the wheel. I have personally witnessed the car at full chat on track several times over the years, and was amazed that such a primitive basic early machine could go so fast.

Like everything else on the car, the gearshift and hand brake are sturdy and made to last.

Oil is fed to the engine via a small tank and hand pump mounted in front of the seats. There is no protection from the heat, fumes, and splattering oil emanating from the motor, save the dusters worn by the driver and mechanic. Nor is their anything to keep the dirt, dust and oil on the roads from clouding the driver’s goggles. We seem like sissies today with our helmets, roll bars, fireproof suits, paved tracks and safety belts.

Water circulation in the cooling system is by thermo-siphon, which relies on the fact that water rises as it gets warmer, causing it to flow through the rather large cooling system. Evaporation is also part of the cooling process, necessitating a large reservoir of water under the driver’s seat. The big engine is thirsty for fuel too, and needs a barrel-shaped 30-gallon gas tank behind the driver that is gravity fed to the carburetor.

Wallace McNair and Anne Thomson sold their Darracq racer a couple of years ago to rally legend Rod Millen, who puts on an event each year in New Zealand called the Leadfoot Festival. No one knows what Millen paid for the car, but it was offered for a cool million dollars, and in today’s market that would certainly be a fair price for one of the very first Grand Prix racers, and the winner, and last surviving Vanderbilt cup car from 1906.

Recently Scott Dixon—four-time world Indy Car champion, now working on his fifth—drove the Darracq in the Leadfoot Festival put on in February every year at Millen’s ranch on the Coromandel Peninsula in New Zealand, and had this to say about the experience: “It is much harder to drive than an Indy Car. You have to brake with the hand brake if you want to slow down at all, and you have to do the advance as you accelerate. It is a real handful.”

Scott also said that: “It was good to be home,” and that: “You have to leave this place to appreciate it.” His contract would not normally allow him to drive other racecars due to insurance problems, but a special dispensation was granted in this case.

They call Dixon the iceman because of his calm understated style, but it is my experience that Kiwis are as given to understatement as we yanks are given to overstatement. When you see Scott on track, he is all pro, and all business. And that was true in the 1906 Darracq too. As he made his runs that weekend, his times came steadily down, and in the end he was throwing this ancient racer around like Louis Wagner himself. It was Scott’s chance to experience a true Grand Prix racer.

SPECIFICATIONS

1906 DARRACQ 120 RACER

Wheelbase: 96”

Track: 53”

Weight: 2,156 pounds

Engine: 14-liter (854 cubic inches), Overhead-valve four-cylinder,cylinders cast in pairs.

Oil system: Total loss

Cooling: Water-cooled by thermo-siphon

Horsepower: 120

Top speed: 108 mph

Fuel capacity: 30 gallons