The Korean War went on from 1950 through 1953 and is often referred to as the “forgotten war.” It is little talked about, though for those who lived it, the memories are still vivid. Also during that same period, another conflict was threatening our shores in the form of an invasion from

Europe, and it too has been largely forgotten. Small, fast, nimble cars from Great Britain, and later Germany and Italy, began appearing on America’s highways and at airport hay bale races. They called them sports cars. Everybody wanted one even though they were noisy, cramped and rough riding.

America had once produced its own very capable sports cars such as the Mercer Raceabout, the Stutz Bearcat and the Kissel Gold Bug during the Jazz Age, but the Great Depression brought the end of them. Sedate sedans and bargain basement business coupes dominated our markets after that, even in the early post-war years. Our returning G.I.s, however, craved the excitement of the more sporty cars from the British Isles, where so many of them had been stationed during the conflict.

As a result, Jaguar XK 120s, Triumph TR2s and MG TCs all became big hits in the States. In fact, they were so popular that American automakers soon began trying to move into the market niche these cars were creating. Most of our early post-war attempts at building sports cars were underfunded and abortive, but then Chevrolet brought out the Corvette, in 1953, and the race was on.

Only the Corvette was still standing in the end, but in addition to the Vette there was the Nash-Healey, Crosley Hot Shot and the Kaiser Darrin, plus Kurtis’ custom offerings, as well as the Muntz Jet; and all were exciting machines in their own right. And all of them are rare and much sought after today. Those who yearned for raw speed could get it in spades with a Kurtis or a Muntz Jet; and if continental elegance was seductive to you, the Nash-Healey or Kaiser Darrin were attractive options. But if you were looking for low-buck racing, the Crosley Hot Shot was irresistible.

Hot Shot

Powel Crosley made a fortune in the 1930s selling inexpensive radios and the first refrigerators with shelves in their doors, called Shelvadors. Flush with success, Crosley decided to try his hand at auto making in 1939. Again, he went for the low-buck end of the market with a tiny car powered by an air-cooled, two-cylinder, Waukeshaw industrial engine. At first, he didn’t market his new offerings through car dealers at all. Instead people purchased them at the local appliance store. The convertible coupe sold for just $325, making the Crosley the lowest-priced automobile in America.

Manufacturing continued until 1942 when war production stopped the building of automobiles, but during the pre-war years Crosley had sold over 2,000 of his tiny machines. And then when the war ended, an all-new Crosley was introduced for 1946 that sported a 44-cubic-inch, four-cylinder, Cobra engine featuring a cylinder block made of copper-brazed sheet steel. Because Crosleys were so small and light, they performed surprisingly well with these tiny, tinny power plants, though electrolysis made them rather short lived.

The Cobra engine was soon replaced by an updated cast iron version with five main bearings and an overhead cam that proved to be quite rugged and dependable. In stock form, these engines made only 26.5 horsepower, but they could propel the Hot Shot to 90 mph. Many of these later engines were breathed upon for use in dirt track midget cars and other racing applications.

Crosleys had a rather high, narrow, squeezed look about them that was dictated by the fact that Powel Crosley insisted they be shipped two abreast on rail cars to save money. In the post-war years, Crosley offered a two-door sedan, a convertible and a station wagon, as well as a sports roadster called the Hot Shot. All came with four-wheel disc brakes, which made it the first car in the U.S. to be so equipped. However, they proved to be trouble-prone in service and were later replaced with conventional drum brakes.

The Crosley Hot Shot looks like a smaller funnier version of Austin-Healey’s Bugeye Sprite. It has no doors, and its suspension is only slightly more sophisticated than that of a go-cart, but it weighs only 1175 pounds, so even though its engine displaces only 722-cc, it goes faster than a bad smell and corners as if it were on rails. In fact, a Hot Shot comported itself well in 1952, at Le Mans, until its voltage regulator failed; and another actually won in its class in the Index of Performance at Sebring in 1951.

A slightly more deluxe version of the Hot Shot, called the Super Sport, was also offered. It sported such decadent amenities as operable doors and a fold-down top. In both cases, the spare tire was mounted on the rear deck, and both the Hot Shot and the Super Sport rode an 85-inch wheelbase. Unfortunately, Crosley’s fortunes went the way of many of the independents, and the company ceased production in mid-1952.

Nash-Healey

Donald Healey came to the United States from England in 1949 to try to purchase some of Cadillac’s new overhead-valve V8s for a sports car he wanted to build, but came up empty handed. He was heading home on the Queen Elizabeth when he met George Mason—C.E.O. of Nash Kelvinator—over dinner on the ship. Healey explained his dilemma to Mason, who offered Nash’s 235-cubic-inch (3.8-liter) inline, six-cylinder engine and a Borg Warner electric overdrive as an alternative.

It appeared, as they say, to be a win-win situation because Healey needed a good engine and Nash was looking to give its rather sober practical line of cars a more glamorous image. The power plants were shipped to England and installed in a widened Healey Silverstone chassis, while the body, originally designed by Healey, was outsourced to Panelcraft sheet metal in Birmingham for the early models, though later Nash-Healeys were fitted with beautiful Pinin Farina bodies in Italy before being shipped back to the States.

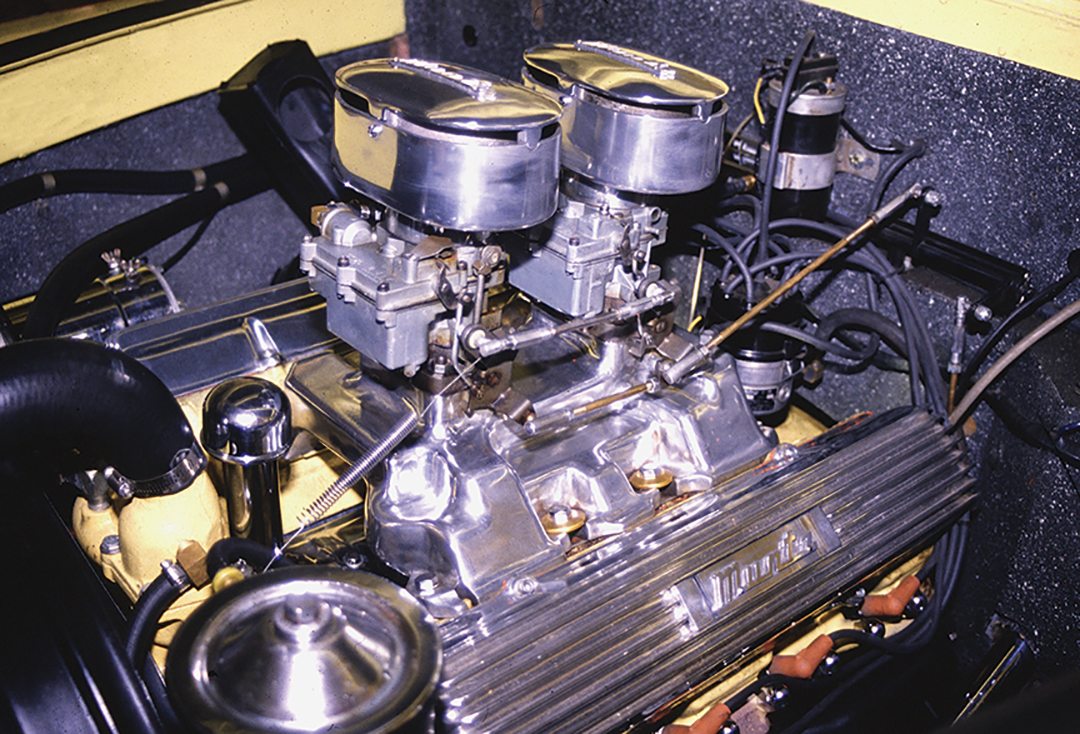

The rather mundane and heavy Nash engine was topped with a special aluminum head and twin carbs for a little more power, and the rolling chassis was then shipped to Italy beginning in 1952, where the body was installed. This made for a handsome sports car that actually acquitted itself well at Le Mans and Sebring, though it never became a big seller due to prices in the $5,000–$6,000 range. All of the shipping back and forth added up to a rather costly product.

The Nash-Healey was billed as America’s first sports car and became Nash’s show car, though it was not actually America’s first, and it did little to convince the buying public that Nash—who made cars driven by pharmacists and family men—was somehow glamorous, even though Superman himself drove a Nash-Healey disguised as Clark Kent on the popular television series of the day, and his love interest Lois Lane drove a Rambler.

When Nash merged with Hudson, in 1954, to become American Motors, the competition was heating up with Chevrolet’s new Corvette and Ford’s Thunderbird, which was in the works, so the Nash-Healey was dropped. Much like the Cadillac Allante in later years, all of the expense of shipping to and from Europe added to the price of the car to the point of making it uncompetitive.

Kaiser Darrin

Howard “Dutch” Darrin had been a custom coachbuilder in Paris during the days of the great classics. His styling graced Duesenbergs, Minervas and Hispano-Suizas, and later he custom-built sporty looking Packard 120 roadsters out of his shop in Hollywood, California. His Packard Darrins were so successful that the prestige automaker offered them in its catalog in the early ’40s, and Darrin is even said to have designed the sleek ’41 Packard Clipper.

Then, during World War II, Henry J. Kaiser, the great construction mogul, ship builder and steel magnate decided to toss his hat into the ring and build his own cars. Like all the American automakers of the time, he too was interested in producing practical sedans that would appeal to the family man or woman. His Darrin-designed, two- and four-door sedans sold well at first, but by the mid-’50s a series of financial setbacks, steel shortages and poor management decisions had combined to doom his foray into auto making.

From 1946 until 1955, the Kaiser-Frazer Corporation produced the Kaiser—a car intended originally to compete with Ford and Chevrolet—and the upscale Frazer intended to compete with Buick, Mercury and Dodge. And later, the Henry J was offered, though it was an ill-timed foray into the compact car field. Also during this period Kaiser Frazer merged with Willys.

Dutch Darrin was never really satisfied with how his passenger car designs had been adapted for production, so he decided to use his own money to produce a prototype Kaiser sports car of his own design. The result was long, low and elegant. It used a Henry J chassis and a Willys F-head, six-cylinder engine that produced 90 horsepower. And, thanks to the car’s rather light 2,175-pound weight, it was reasonably quick for its day. A few were even treated to McCulloch superchargers, making them one of the hotter offerings of 1954.

Henry Kaiser was miffed that Darrin would take such liberties until he found out that Darrin had built the car on his own time and with his own money. And then Kaiser’s wife saw the handsome, KD-161 convertible and fell in love with it. She remarked that it was the most beautiful thing she had ever seen. That was enough to get the car into limited production. The body was all fiberglass and the doors slid forward into the long front fenders. The trunk and tonneau opened rearward and was all one piece. The Darrin’s top could be partially folded to become a landau top, or folded into the tonneau for a sleeker look.

The problem, though, was the Kaiser Darrin was too little too late. Apparently, the last 100 of them were left out in the elements when production stopped at Willow Run in 1955. Dutch Darrin couldn’t bear to see his creations languish, so he bought up the whole remaining lot of them and later powered several of them with Lincoln engines, making them truly quick, as well as graceful-looking.

Kurtis Kraft

How would you like to own a race-winning early ’50s Indianapolis car with fenders and headlights so you could take it out on the street? Well, that is the exciting reality for a few lucky owners of the remaining Kurtis 500S series sports cars. They are a bit wider than the Indy racers from which they were derived so two people can ride in them, but otherwise they are basically street legal Indianapolis roadsters capable of 142 miles an hour in street trim running a stroked Mercury flathead.

People who know the history of the Indianapolis 500 know that Frank Kurtis’ cars dominated the event in the late ’40s and early ’50s. Nothing could touch them. In 1954, Kurtis Kraft entries took 1st, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 8th, 9th and 10th places inn the 500! To finance his racing, Kurtis decided to field a line of sports cars built using the same basic design as his racecars. Nothing could touch Kurtis cars in competition on the ovals, and the same was true on the sports car circuits.

You got American muscle in a lightweight tubular space frame, with a fiberglass body, torsion bar suspension and beam axles; but only the bare minimum of creature comforts, which made for some extremely quick machinery. These were really, as much as anything, very sophisticated hot rods much like the British American hybrid Cadillac Allards of the same period.

Kurtis’ early street offerings were available with super-tuned Mercury flathead engines, as well as Oldsmobile, Cadillac and Chrysler Hemi V8s, and all of them went faster than Ivanka Trump’s clothing budget. Unfortunately, Kurtis’ Indy cars were soon copied and improved upon by builders with bigger bankrolls, so by the late ’50s they were no longer competitive. And Frank Kurtis didn’t have the resources to compete in the manufacture of sports cars with the likes of Jaguar, Corvette and Porsche either, so he, too, ceased producing them by the mid-’50s.

Kurtis? That’s what the Muntz Jet really was.

Muntz Jet

Earl “Madman” Muntz’s story is as fascinating as the sports cars he produced in the early to mid-’50s. He started selling used cars in Chicago and then gave himself his trademark nickname when he was a car dealer in post-war Southern California, where he would go on television and radio and rave that he was completely mad, and that he wanted to give the cars away, but Mrs. Muntz wouldn’t let him. “WE’RE CRAAAZY!” he would scream. He even stated in his ads that if he didn’t sell a certain car by the end of the day, he would smash it with a sledgehammer. He was also famous for strutting around his car lot dressed in red long johns and a Napoleonic three-cornered hat, which was an obvious allusion to his madman image.

Muntz amassed a fortune in just a few years selling automobiles, and also had the most successful Kaiser Frazer dealership in the United States. He then turned his attentions to making and marketing television sets just as that market opened up in the late ’40s. Muntz televisions sold like Big Macs and made yet another fortune for him. But one venture that didn’t make him any money was his foray into auto making with the Muntz Road Jet.

In 1950, Muntz had a falling out with Henry J. Kaiser, so he purchased all the tooling and dies for one of Frank Kurtis’ sports cars and then—along with Kurtis and race driver Sam Hanks—set about reworking the car to give it wider appeal. There were 39, two-seat cars built with Cadillac engines and Hydramatic transmissions, the wheelbase was lengthened 13 inches to allow for a back seat, and numerous suspension tweaks were added to make the car more roadworthy.

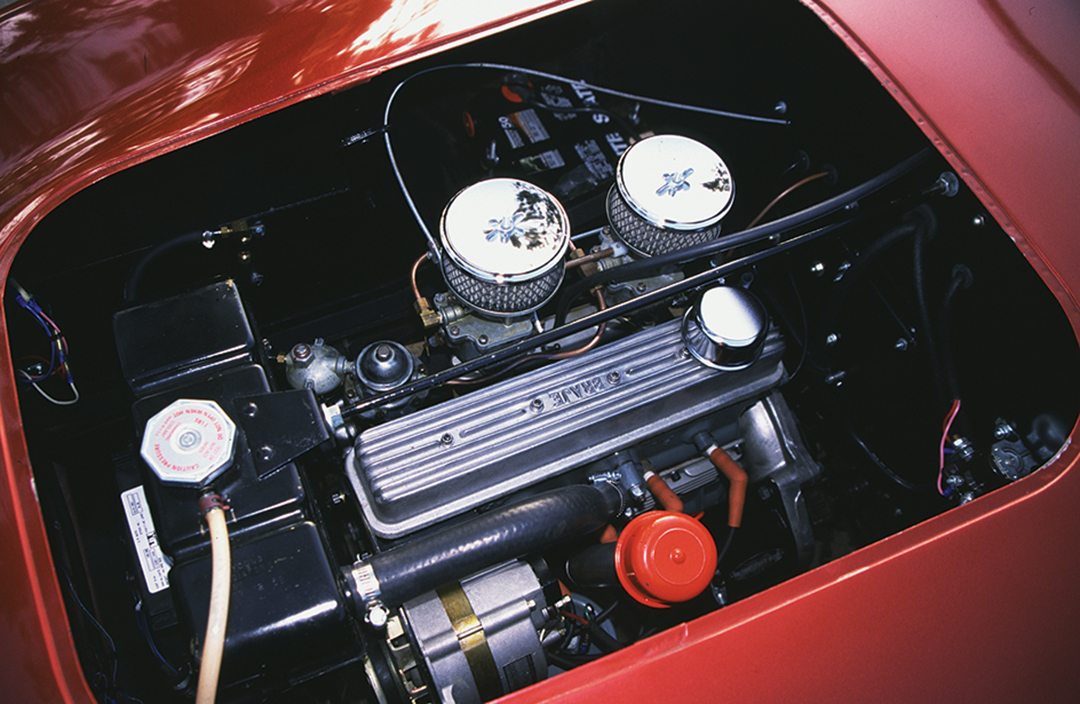

Early Muntz Jets were Cadillac-powered, but later, super-tuned Lincoln engines were used.

The early Muntz cars were built in Evansville, Indiana, and came with 5.5-liter Cadillac V8s, but later, production was moved to Chicago where Lincoln’s flatheads, and eventually their overhead valve engines, were installed. Much of the Muntz consisted of Ford components, and Ford dealers even agreed to service them.

The first Muntz Jets equipped with Cadillac engines and Hydramatic transmissions could do 0-80 mph in 9 second,s and it is said that the Cadillac equipped Muntz could cruise at 125 mph with plenty of revs to spare. Later, overhead valve, Lincoln-powered cars were even quicker.

Muntz Jets built from 1950-’54 were very popular with Hollywood celebrities who had them accessorized to the hilt with padded dashes, bars and zebra or emu skin upholstery. And most Muntz Jets were painted bright colors such as pink, baby blue or lemon yellow. Also, aftermarket speed equipment could be ordered installed at the factory, making the Muntz even quicker. Even so, success was limited by the $5,500 base sales price.

Even at that price, Muntz claimed to have lost $1,000 dollars on each one he made. The flow-through body design required a lot of custom fitting and leading, and the small total production didn’t allow for any economy of scale by mass discount buying of components. In fact, by 1954, Muntz was in a bad way financially, having lost money on his cars; and not having prepared for the advent of color television had cut into sales in that area too.

Muntz filed for Chapter 11 that year, but went on to pioneer four- and eight-track stereo, along with other creative endeavors that made him yet another fortune. Earl Muntz died in 1987, and at that time he was poised to do it all again by pioneering cell phone technology. Muntz claimed that there were 394 Jets built, of which only 49 are known to have survived.

All of these pioneering post-war sports cars were innovative, and most of them were under-funded, and ultimately doomed by the major manufacturers. Their visionary builders, however, could see where the future lay, and their efforts inspired successes such as the Corvette, Thunderbird (which was said to be inspired by the Muntz Jet) and later the Mustang and Shelby Cobra.

Today, any one of these early American sports cars in restorable condition would be a great find, and a rare and wonderful machine to drive.