We walk through Don Murray’s spectacular classic and exotic car collection and dealership called Mesa Concours Cars in southern California, past Ferraris, Porsches, Aston Martins and other automotive masterworks, to arrive at a tiny blue Bug Eye roadster parked at the far end, in the corner, in the dark. This is most assuredly not just any Bug Eye though. I am talking about a very special 1961 Sebring Austin-Healey Sprite Mk1 that finished 8thin the short four-hour race that year.

It was campaigned by none other than Briggs Cunningham as part of a team assembled by the famous racer and collector that also included Stirling Moss and Bruce McLaren, two giants of motor racing. However, physically, the aforementioned gentlemen were diminutive in stature. Why does that matter? I’ll get to that later. And by the way, Sir Stirling’s sister also participated in the short race in a specially prepared Sprite coupe, as did he.

The car’s perky Bug Eye headlights (Frog Eye if you are European) and smiling grille make it look like an eager puppy waiting for a treat. There is no way for it to know that I am about to give it a damn good thrashing. We push the minuscule machine out into the sunlight and Derek Boyks— Murray’s chief mechanic— cranks it up. It coughs and spits before launching into a buzzy, soaring hysterical scream.

Derek lets it warm up a little and then drives it a couple of miles over to a vast county fairground parking lot that happens to be in the vicinity, while we follow behind. I stay a few car-lengths back in my 1958 Chevrolet pickup so I can keep track of him. The Sprite is so small that if I get any closer it will disappear below the horizon of my hood.

Derek— who is a tall slim guy —stumbles out, stretches and motions for me to get in. I am then confronted with the problem of stuffing my own 6’2” 210 pound mass into this Lilliputian roadster. It is plainly not designed for a bloke of my displacement. It is a truly little car, more suited to little people.

I open the tiny frail door, wedge my tuchas onto the teensy tuffet that serves as a seat, and then swing my legs around—pulling up on my ankles with my hands into an embryonic position in order to get my feet past the A-pillar. The steering is on the British side. Once in, the car is tight but drivable, though spartan. It’s a racer after all.

There is some black trim over the dash panel, and there are the little bucket seats, but that is it in terms of an interior. Every other surface is bare sheet aluminum welded together to make the structure of the car. The insides of the doors are the outsides of the doors, and the flimsy framework that reinforces them makes a sort of de facto recess at the bottom for sunglasses and maps. There are no exterior door handles. There are just sliding knobs on the inside to open the doors, and there are no windows to roll up. Real men don’t need windows, and besides, glass is heavy.

The full array of Smiths analog gauges is big and easy to read. The steering wheel is big too, and a bit close to my torso. Also, as is typical of British sports cars, the pedals are no bigger than a lady’s thumb, and as close together as the fingers on her hand. It occurs to me that I should have brought a pair of pointy ballet slippers, because my 11½ C Nikes chafe and scrub against each other when I’m shifting and braking. Sir Stirling, and Bruce McLaren’s feet were very likely smaller than mine, and the proximity of the pedals undoubtedly made for deft heel-and-toe shifting for them, but they are awkward for my use.

The short-throw four-speed transmission shifts cleanly and precisely. The clutch is beefy and somewhat abrupt and the engine needs a bit of revving to make power, but then we are rapidly away. Acceleration is instant and we make 80 miles per hour before we reach the end of the immense parking area. I swing around and the little roadster corners obediently, with no lean and just a bit of understeer. The handling is nearly perfect.

As Sir Stirling himself said when interviewed about the Sprites: “They were very forgiving, and good for somebody just learning to race. They were also very stable in bad weather too.” When asked why he raced Sprites in the short race, even though he had landed a Ferrari for the 12-hour event, he replied that Donald Healey attracted a lot of “crumpet” which was the British equivalent of the contemporaneous American slang term “chicks” or the Australian “Sheilas.”

I am suddenly consumed by the uncontrollable passion to put my foot in it and slalom back through the big plastic barriers that divide the parking lot and all I can say is WOW! I have driven a lot of fast exotic sports and muscle cars in my day, but I have never had more unadulterated fun in any car than this piquant petit roadster.

Our Sebring Sprite is powered by a highly excitable 948-cc, punched out to 998-cc, Austin A series engine that is much like those used in the Morris Minors of the day, from which the Sprite running gear was adapted. These solid little engines were put into many small British cars in later years in one form or another, and could be tuned to nearly double their stock 48 horsepower. These pint-size power plants were designed to be sturdy, under-stressed and economical, so they had a lot of potential when it came to race tuning.

The first production model Sprite Mk1 offered in 1959 was steel bodied, but even then it only weighed 1,411 pounds. However, the Sebring racers, of which there were five built for 1961 at the Warwick experimental shop, were mostly clad in fiberglass with aluminum doors. And this combination lightened the car considerably.

The works Sebring engine sports an 1100 head, twin 1 1/4 S.U.s, 998-cc rods and nitrided pistons, plus a forged crank and a free-flowing exhaust header. All that and a hot cam turn this little Swiss watch of an engine into a one that is a danger to itself and others. And along with all this go-fast stuff, Girling front disc brakes, and eight-inch rear drum brakes were added to make the thing stop just as fast.

The Austin Healey Sprite made its debut in 1958 in Monte Carlo just before the Monaco Grand Prix. Donald Healey had been racing and designing race cars since World War I for Triumph and other British companies, and opened his own company in 1945 to produce sports and racing machines. Books could be written on the extensive crossbreeding and rebadging of British automobiles from the nineteen thirties on, but suffice it to say, there never was a purebred Healey automobile.

All of Donald Healey’s creations were assembled using engines and drivelines available from bigger companies such as Austin, Morris, Triumph and Riley. And then, in 1951, the company even produced a sports car using big Nash overhead valve, inline six cylinder engines and U.S. made Borg Warner three-speed transmissions with electric overdrive.

They were called Nash Healeys, appropriately enough, and they were rather dashing looking roadsters that competed successfully at Le Mans, where one took fourth place in 1950. They appeared also in the Mille Miglia, in which they took part over several years. But the Nash Healey turned out to be too expensive to be a commercial success.

And then, in 1953, Healey came out with his most successful sports car, the Austin-Healey 100, which evolved into the Mk 1 3000 in 1959 to become one of the most successful and sought after sports cars of all time. In fact, Austin-Healey 3000 roadsters are still being raced at vintage events here and abroad. But the Mk 1 was an expensive sports car also, which still left a marketing niche open for an inexpensive alterative for the average Clive or Nigel to enjoy a bit of competition on the weekends.

It was to that end that the Austin-Healey Sprite was developed. The goal was to produce a sports car, “that a chap could keep in his bike shed” and to do that they went with the humble Morris Minor drive train and steering gear, both of which were outstanding for what they were designed to do. The Morris Minor handles as if it’s on rails, and though its tiny engine makes meager power, it could be tuned to do amazing things, like propel Stirling Moss, Bruce McLaren and Briggs Cunningham to top slots at Sebring in 1961.

Unit-body construction was used, and the body shell essentially consisted of a one-piece bonnet and boot, as the British would say. The hood, fenders and grille, e.g. the front clip, lifted up as a unit from the cowl and was all one piece. The rear of the car behind the doors was also one piece, so to get into what would be the trunk, you had to pull the seat forward and tunnel in from the passenger compartment. A trunk opening would have cost more money and added weight. That was also true for the folding headlights that appeared originally on the prototype. They too were jettisoned to save both weight and money, resulting in the frog, or Bug Eye look.

The little roadster was such a success on the track and with the public that an MG badge-engineered version of the car appeared in 1961 as well, and was called the Midget – a name revived from the company’s depression era sports cars that ultimately used the Austin Ten motor of the time. Aficionados often refer to the Sprites and Midgets collectively as Spridgets.

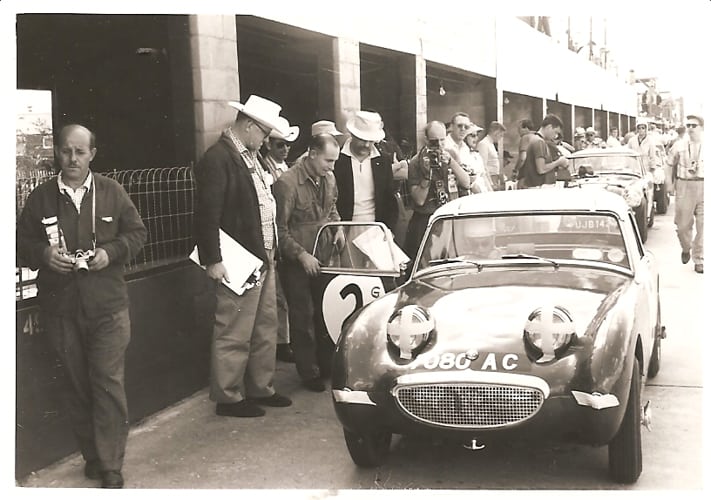

Seven Sebring Sprites were campaigned in the Sebring long-distance races of 1961. Five Healey-prepared examples were fielded for Ed Leavens, Briggs Cunningham, Dick Thompson, Bruce McLaren and Walt Hansgen. Sir Stirling and his sister Pat, who was Britain’s most successful female driver of the era, piloted two Sprite coupes built by John Sprinzel.

The Sebring Sprites finished in six of the top eight spots in the four-hour race for one-liter cars in 1961. The Bug Eye contingent took third through eighth with Walt Hansgen taking third and Bruce McLaren coming in fourth. Stirling Moss grabbed fifth with Pat Moss coming in seventh, with Briggs Cunningham finishing eighth in the example we tested.

In the 12-hour race the next day, Sebring Sprites driven by Ed Leavens, John Colgate, Joe Buzetta, Glen Carlson, Cyril Simson and future Formula I competitor Paul Hawkens did well too, finishing second, third and fourth in class, and fifteenth, twenty-fifth and thirty-seventh over all.

As with so many old racecars, after 1961, Cunningham’s Sebring Sprite was subjected to the usual indignities that come after being one of last year’s top competitors. It got handed down to lesser drivers and competed in lesser events, and was hopped up and bashed up in an effort to keep on winning. Our example was later purchased by Bill Wood, an avid Austin-Healey specialist, in Egremont, Massachusetts who restored it and then sold it to Jeff Brenner. Here is what Wood had to say:

“I purchased the car from a body shop in Springfield, Massachusetts as salvage, not knowing at the time it was a special car. My son was restoring a square-body Sprite and needed a motor for it, so the original Sebring motor went into his restoration and went the way of all flesh. I put the rolling chassis together and in so doing, found from Geoff Healey’s records which I still have, that it was one of the five 1961 cars. It had been sandblasted at the body shop, so I re-made all the aluminum panels for the doors and inner fender panels (I still have in the attic the original factory panels).

“I got a new right-hand dash, from Geoff’s garage while visiting at his home at Warwick, a steering wheel from California, and the original type brakes from England. The grille was re-done and re-plated and the two fiberglass panels for the front fenders were re-made by me personally. I got the large tachometer from England; the two hold-downs for the bonnet were reconstructed, a la 100S specs. This is all from memory of course.”

The car eventually made its way to the west coast, and finally to Don Murray’s collection where it has received a thorough freshening up so it runs and looks just as it did back in the day, and I can attest to that. Unfortunately, my moments of ecstatic unruly behavior at the fairgrounds had to end, and I felt a little like a kid leaving Disneyland at the end of the day; excited but a little reluctant because I could have gone on tossing that little racer around forever.

But all good things must come to an end. To eject myself from the Sprite, I place my right hand on the rear quarter and my left on the on the windshield frame, and then pop myself from the seat, thrusting my right hand briefly on the pavement to steady myself as I stumble away. I then dust of my hands off while giving Derek Boyks and our photographer a threatening look to say: “Okay guys, the fun is over.”