The 1950s and 1960s were a time of rapid change in both the road and racecar world. Technology was advancing quickly and with this advancement, it became increasingly harder and harder for a lone individual—either engineer or visionary—to be solely responsible for a complete automobile. Yet, some amazing vehicles were given birth during this time by some of the last of these automotive prodigies. One such automotive savant was Italian Giotto Bizzarrini. A tenacious and talented engineer and development driver, Bizzarrini either created or played a major role in some of the most iconic cars of the 1960s, including several built under his own name. Any true understanding of Bizzarrini’s cars, however, first requires an understanding of the man, as the two are virtually inseparable.

Photo: Joon Lim

Born Survivor

Giotto Bizzarrini was born in June 6, 1926, in Quercianella, near Livorno, Italy. Born into a long line of engineers, it is perhaps not surprising that Bizzarrini would gravitate toward things mechanical. However, his early childhood years were more dominated by soccer and hunting, at least until World War II intervened. When the war broke out, Giotto’s father took up arms against the Germans, leaving young Giotto behind to fend for his family. During the war years, times were tough and much of what the Bizzarrini family had to eat ended up coming from Giotto’s hunting prowess. Bizzarrini would look back on these years of deprivation and state, “That period really influenced me for the rest of my life. It made me into a survivor, somewhat of a maverick.”

After the war, life again took on some sense of normalcy, resulting in Giotto enrolling at the University of Pisa to study airplane design and aerodynamics. Fortunately, his course work took something of a detour when, for his thesis project, he elected to adapt some of the aerodynamic principles he had learned onto a lowly Fiat Topolino. The result was a lowered and more streamlined machine that benefitted not only from better aerodynamics, but also a much improved chassis and fine-tuned engine with Siata OHV head. His instructors were mightily impressed with his car and thus granted him a degree in mechanical engineering in July 1953. Just four months later, he would marry his girlfriend, Rosanna Mancini.

Photo: Casey Annis

Alfa Romeo

While Bizzarrini worked briefly for a weapons manufacturer, by the summer of 1954 he had landed a job working in the experimental department at Alfa Romeo. It was here that he was taken under the wing of Consalvo Sanesi, the famed Alfa test driver, as well as Alfa’s Chief Engineer, Orazio Satta. Bizzarrini also developed a friendship with another fellow Tuscan engineer who would figure prominently in his later work, Carlo Chiti. Despite the deep pool of engineering talent at Alfa, it was his work with Sanesi, in particular, that would forever change the arc of Bizzarrini’s career, because it was Sanesi who really taught him how to drive a car, how to test it. Once Bizzarrini was able to meld this specialized skill, with his formal engineering training, he became part of a very small and exclusive automotive club. As an engineer, he didn’t need to interpret the feedback from a driver who might not fully understand the engineering principles of what he was experiencing. Bizzarrini could push a car to its limits and immediately come back and modify and improve it himself. Like contemporaries Colin Chapman and Rudolph Uhlenhaut, this combination of talents would carry Bizzarrini far.

Modena Beckons

Bizzarrini only got to work at Alfa Romeo for three years, before he received a fortuitous phone call from his cousin, in 1957. As luck would have it, his cousin was a good friend with Andrea Fraschetti, who happened to be chief engineer at Ferrari at that time. Fraschetti let his friend know that one of Ferrari’s test drivers had been killed and that the Commendatore was looking for a replacement…preferably one with an engineering background. After interviewing with Ferrari himself, Bizzarrini was hired and was even able to bring Carlo Chiti to Modena for good measure.

At Ferrari, Bizzarrini shined, resulting in him becoming the director of production and testing control by 1958. During this period, he worked together with Chiti on the V12 engine for the fabled Testa Rossa, as well as doing extensive development work on such notable Ferraris as the 250 GT Ellena, the 250 SWB, the 250 California Spider and the 250 GT 2+2.

However, by the spring of 1961, Enzo Ferrari had grown worried. Jaguar had just unveiled their new E-Type and the Commendatore was concerned that this new cat might become a real threat to his dominance of the GT categories. With this in mind, Ferrari took Bizzarrini aside and instructed him to assemble a handful of technicians to help develop a new and improved version of the 250 GT that could see off the E-Type. Bizzarrini was admonished to keep this project secret, so much so that he wasn’t to tell even Chiti about it!

Starting with an SWB (chassis #2053), Bizzarrini set about completely re-envisioning the car. He moved the engine back, lowered the center of gravity, gave the car a lower nose and a fastback silhouette and went to work on the suspension. Since the outer bodywork was crudely cobbled together, Bizzarrini nicknamed the prototype Il Mostro or The Monster, and while it may have looked like a monster, on the track it performed like a beast, consistently posting lap times several seconds faster than the 250 SWB that it sprang from—but then the purge intervened.

Everyone Out

As Bizzarrini settled into the work of sorting out his 250 Mostro, in November of 1961, trouble was brewing in the front office. For some time, Ferrari’s head of sales, Gerolamo Gandini, had been concerned with the amount of “meddling” that he felt Enzo Ferrari’s wife Laura was doing in the business’ affairs. In November, this came to head when he told Enzo that either she had to back off, or else he would have to leave. As might be expected, Enzo promptly showed him the door.

Unfortunately, Gandini was not only a major architect of Ferrari’s postwar financial success, he was also well liked by his colleagues, including Carlo Chiti, team manager Romolo Tavoni and administrative manager Ermanno Della Casa. When word spread that Gandini had been let go, the trio entreated Bizzarrini to join them in presenting a unified front to convince Enzo that he should re-hire Gandini…for the good of the company. Surely, once Ferrari saw that all his top management and engineering staff were in support of Gandini, he’d have no choice but to reconsider? In fact, he fired the lot of them on the spot! As a result, a very young engineer by the name of Mauro Forghieri was given the task of doing the final fettling on Il Mostro, which would go on to be renamed the Ferrari 250 GTO.

A New Beginning

Somewhat bewildered by the suddenness of their ouster, Chiti, Bizzarrini and Gandini quickly found their feet. By February of 1962, the Ferrari refugees secured funding from two industrialists, Giorgio Billi and Count Giovanni Volpi, to start their own company, with the goal being to beat Ferrari at his own game. This new concern was dubbed Automobili Turismo e Sport (ATS) and had the lofty goals of creating both a world-class GT car for the road, as well as a competitive Formula One program.

However, right from the very beginning there were fundamental differences in opinion on both strategic and engineering goals. Chiti favored focusing on a V8 powerplant, while Bizzarrini preferred a V12. Likewise, at the investor level, Volpi and Billi also disagreed on the best direction for ATS, resulting in two separate political camps forming within the company—Chiti and Billi on one side and Volpi, Gandini and Bizzarrini on the other. After barely six months, Bizzarrini lost patience with the battling and left ATS to go out on his own. This would neither be the first nor last time that Bizzarrini would fall out with co-workers or investors. According to Bizzarrini himself, “I cannot tolerate being bossed around, being told to do something. I never used diplomacy. I like to be free to express what I want, so diplomacy does not work.”

Shortly after Bizzarrini departed, Volpi and Gandini took a buyout offer from Balli and they, too, left. ATS, under Chiti and Billi, descended into bankruptcy by 1965.

Autostar

Bizzarrini returned to his ancestral roots in Livorno and set up his own shop, which he called Austostar. Here, he began taking on projects on a contract/consultancy basis with one of the first being a redesign of the Ferrari 250 GTO for Count Volpi, which famously became known as the “Breadvan.” During this same period, Bizzarrini also took on development work for Autocostruzioni Societá per Azioni (ASA) on their diminutive 1000 GT project. It was through his work with ASA that Bizzarrini was introduced to Ferrucio Lamborghini, who was looking for someone to design a V12 engine for his new sports car, the 350GT. Fortunately, for both Lamborghini and Bizzarrini, Giotto still had his design for the V12 engine that was never developed at ATS. While Bizzarrini did deliver a 3.5-liter, V12 engine that surpassed Lamborghini’s horsepower specifications, the duo had a falling out over final development and specifications, resulting in another less than amicable parting of the ways.

Rivolta

In the early 1960s, Renzo Rivolta’s Iso Company was successfully manufacturing a wide variety of products, everything from scooters and refrigerators to motorcycles and the Isetta “bubble car,” under license. Like Lamborghini, Rivolta also felt that there was a market for a new Italian GT, though he felt it should be built around much simpler and more reliable mechanicals than the temperamental engines favored by Ferrari and Maserati.

Rivolta was intrigued by the British-built Gordon, which featured a stylish, Bertone-designed body, with a tried-and-true Chevrolet V8 engine sourced from the Corvette. Rivolta decided that this approach was the one he wanted to emulate for his GT, so he asked Bizzarrini to test the Gordon and then apply those principles to the new Iso GT. While Bizzarrini thought the Gordon had appalling handling characteristics, he was positively smitten by the power and flexibility of the Chevrolet V8 engine. For Bizzarrini, this initial contact with the Chevrolet V8 would become the foundation for much of his future work.

Over the next few years, Bizzarrini would work with Rivolta to design first the Iso Rivolta, a 2+2 GT car based around unit body construction that lent itself to mass production (Iso’s goal being 10 Rivoltas per day), and then the sportier 2-seat Iso Grifo. While Bizzarrini designed the Iso Grifo (also known as the A3/L) road car, he was also keen to develop it for racing. Bizzarini created the A3/C (“C” for corsa or race), which enjoyed a fair bit of success in long distance endurance racing, including a class victory at Le Mans in 1965.

Despite the Grifo’s success, by 1965, Bizzarrini and Rivolta also began to butt heads over direction. Rivolta wanted to concentrate on the mass production of the existing cars, while Bizzarrini was only interested in the racing and constant evolution of the line. As a result, in the summer of 1965, Bizzarrini went through another rancorous “separation,” this time with Rivolta, that ultimately left him with certain rights to continue production of the A3 Grifo, with parts sourced from Iso. After many years of struggling with partners and investors, Bizzarrini was now well and truly on his own, as a constructor.

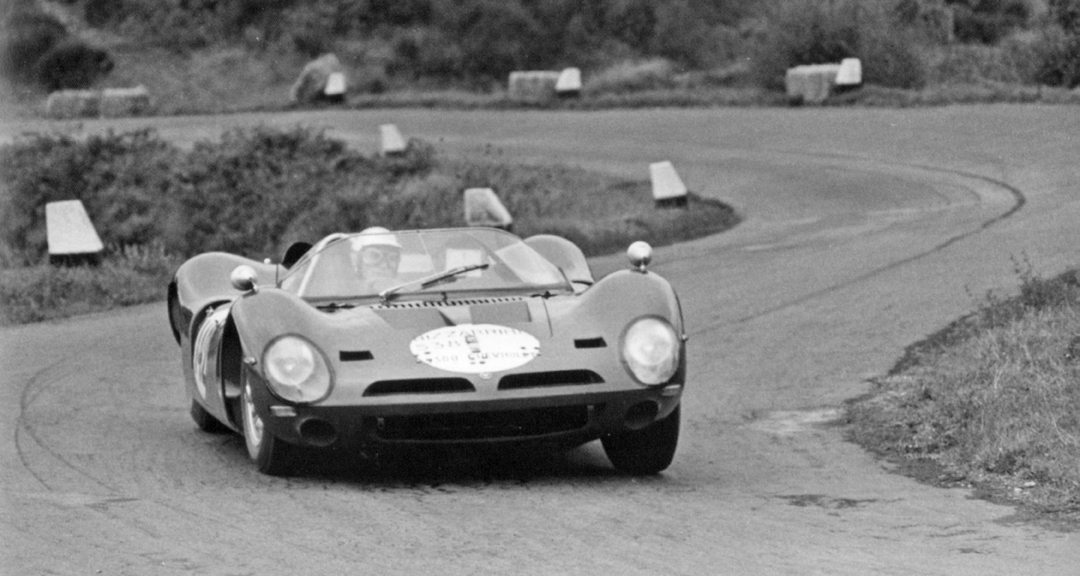

P538

Now out on his own, Bizzarrini was free to pursue what he felt was the best course. With his own production of the A3 underway (now dubbed the Bizzarrini GT Strada 5300), Giotto felt that continued success in endurance racing would, like Ferrari, secure his company’s future. As such, Bizzarrini dove right in at the deep end, electing to build a mid-engine prototype to go head-to-head with Ferrari and the Ford GT40, at Le Mans. Bizzarrini worked on the design of his mid-engine car—based around his preferred power plant, the Chevrolet 327 V8—in the beginning of 1965, with construction of the prototype starting in the fall and the first chassis being completed in November.

He designed his new racecar around a spaceframe chassis that included independent front and rear suspension, with unequal length wishbones at the front and a race-tuned Chevrolet 327 that breathed through four sidedraft Webers mounted on his own custom manifold and feeding power through a ZF 5-speed gearbox. For construction of his curvaceous fiberglass body, Bizzarrini farmed the work out to Vicenzo Catarsi’s boat building business in Vada-Cecina. The new car would be known as the P538, “P” for Posteriore or rear-engined, “5.3” for its displacement in liters and “8” for the number of cylinders. The plan was to construct two chassis to compete in that year’s 24 Hours of Le Mans.

However, before Giotto could install the Chevrolet power plant in the first chassis (001), Bizzarrini was approached by American racer Mike Gammino, who had raced an A3/C at Sebing in 1965. Gammino relayed that he had asked Ferrari for a mid-engine racecar to compete in the Can-Am series but was rebuffed. However, a chance meeting with Ferrucio Lamborghini at the New York Auto Show convinced him that Bizzarrini’s 3.5-liter Lamborghini engine might be the perfect power plant and would Giotto consider building him a racecar around it? Bizzarrini replied that he already had the car half built and that he would send him a P538, with the Lamborghini engine in it!

As a result, P538 Chassis 001 was completed in January 1966 and featured a chassis made of thick-walled, rectangular tubing and a race-tuned Lamborghini engine. Giotto himself gave the new car its first shakedown run, in February, at the nearby La Spianate e Castiglioncello circuit. He then handed the car over to Swiss racer Edgar Berney for more testing. Within five minutes, Berney lost control on a wet patch, flipping the car and badly damaging it.

Now faced with no time to complete a third chassis to satisfy his commitment to Gammino, Bizzarrini ordered Chassis 001 striped and the Lamborghini engine installed into Chassis 002, which was one of two Le Mans specification chassis built with more robust round tubing, instead of the heavy rectangular. With Chassis 002 sent to Gammino in the USA, this meant that Bizzarrini would only have Chassis 003 to enter for Le Mans. Since he had already registered for a two-car team, he elected to enter an A3/C for Sam Posey and Massimo Natili as well.

At Le Mans, the Swiss driving duo of Edgar Berney and Andre Wicky qualified the P538/003 (race number 10) in 40th position. However, when the French Tricolore fell, star-crossed Berney jumped into the Bizzarrini and stomped down on the accelerator, only to have the P538 spin out in front of the back half of the field—narrowly missing the Posey A3/C in the process! Luckily, Berney was able to recover and chase the tail end of the field, though he quickly discovered that a serious imbalance had developed in the car. On the seventh lap he came into the pits to have the tires changed, but in jacking up the car, one of the frame rails that carried the cooling water to the front of the car was damaged and the P538 became the first retirement of the race on the 54th lap. An inauspicious start to Bizzarrini’s Ferrari killer.

End of a Dream

Sadly, the P538’s on-track fortunes that year didn’t get much better. Gammino suffered a DNF, with a cracked sump, at Bridgehampton, the one and only Can-Am race that he competed in with the car. At Mugello, on July 17, Antonio “Beppe” Neri retired Chassis 003, while on October 30, G. Naddeo drove Chassis 003 to its one and only finish, a 4th place in the Trofeo Cittá di Orivetto.

For 1967, Giotto Bizzarrini attempted to enter Chassis 003 at Le Mans again, only now as an enclosed car since open cars were no longer allowed. However, the ACO rejected the car at scrutineering, without ever giving a satisfactory answer why. Some Bizzarrini fans believe it may have been the hand of Enzo Ferrari, seeking a little revenge, but most likely it was the inspectors seeing through the hastily constructed targa top to enclose last year’s open car!

Sadly, this would prove the end of the P538 saga for several reasons. First, the CSI ruling body subsequently declared that for the following year’s race, prototype engines would be limited to five liters, rendering the Chevrolet 327 ineligible. Theoretically, Bizzarrini could have run the P538 in Group 4, with the Lamborghini engine, but Group 4 required a production run of 50 cars, which the now struggling Bizzarrini could neither afford nor scale up to produce. While the P538 would not race competitively again, late in 1967, Bizzarrini did build a special, fourth chassis, as an enclosed road car for one of the heirs to the Italian House of Savoy, Amedeo Duca d’Aosta.

While Bizzarrini had gambled that his P538 design would be competitive throughout the ’60s, it’s all too brief and disappointing career ended up costing the fledgling manufacturer almost 20 million lira. This, combined with problems on the road car production side, ultimately led to Bizzarrini being dissolved by his creditors in 1968.

A Final Encore

After the dissolution of his eponymous company, Giotto Bizzarrini would continue to consult and do development work under the Autocostruzione name. And, in the 1970s, he was commissioned to build two more P538 chassis for collectors. But in 2005, Giotto was approached by Bizzarrini enthusiast Jack Koobs de Hartog about undertaking one final project. In honor of 2006 being the P538’s 40th Le Mans anniversary—and Giotto’s 80th birthday!—Bizzarrini was asked if he would consider building three, special “Anniversario” P538. At first, Giotto was hesitant, as he doubted many of the parts could be sourced to build a true P538, as it existed in 1966. But de Hartog and his partner Peter Opper convinced Bizzarrini that their company CCM GmbH, in Germany, was able to source or reproduce all the necessary components.

By December of 2005, Bizzarrini was nearly complete with the first chassis. All three chassis would be constructed using the Le Mans specification round tubing, rather than the rectangular tubing of the prototype. Giotto himself built all three of the chassis from original drawings, period photographs, and in some cases memory. Using the original moulds, sourced from Vicenzo Catarsi, Giotto’s wife Rosanna hand laid up each of the three fiberglass bodies.

When completed in 2006, one chassis (P538*V12*1) was built for the road and featured a Lamborghini V12, left-hand drive and a hard top reminiscent of the road going Duca d’Aosta P538. The other two chassis (P538*80*1LM/A and P538*80*2LM/A) were built to be exact re-creations of Chassis 003, as it raced at Le Mans in 1966. Our test car (P538*80*2LM/A) was built for a Californian car collector and featured a race-tuned 1965 Chevrolet 327 V8 with Bizzarrini manifold and four side draft Webers putting 420-hp through its ZF 5-speed gearbox.

Behind the Wheel

Sitting silently in the Southern California sunshine, the Bizzarrini looks almost fluid. Walking around the long, low slung machine, one can see a number of “Ferrari-like” styling cues in various parts of the car’s fiberglass body—a little Ferrari Dino here, shades of the 275 P there. However, the nose with its covered headlights and twin nostrils either side of the midline is pure Bizzarrini—a distinctive styling carryover from the earlier A3/C racing Grifos. Circling around the rear of the car, the P538 sports a slightly odd bulge hanging under the rear of car like some surreal insect’s pregnant abdomen, which houses the sports racer’s FIA-required spare tire (still a requirement at Le Mans in 1966).

Pushing the delicate pushbutton handle on the right-side door releases the latch and reveals an all black cockpit dominated by wide, vinyl-covered sills. Being a purpose-built, endurance racing machine, the pair of seats are centrally located, deep in the cockpit and require a certain amount of machinations to climb into. One needs to step over the wide sill, either placing the left foot in the seat itself or on the far side of the floor, bracing the arms with the roll hoop and the steering wheel, while swinging into the seat and under the wood-rimmed steering wheel! Once in the driver’s seat, one has the sensation of sitting deep within the racecar, as the driver literally sits on the floorpan, with the windshield fairly far forward and the side windows and doors a good distance away due to the wide sills. Since this is a 1960s Italian purpose-built racecar, driving position for a taller driver is somewhat challenging. For my 6-foot frame, I find that with my feet on the closely placed pedals, my legs are partially splayed around the steering wheel with knees pretty firmly “braced” or jammed against the bottom of the dashboard.

To the right of the steering wheel is a simple key, which is turned to the first position before reaching to the center of the dashboard to throw the first of three, unmarked toggle switches, which turn on the ignition and the two supplemental electrical fuel pumps. With the pumps whirring away in the sills, to either side of the driver, the key is then turned to the second position to engage the starter. After a second or two of deep mechanical cranking noises as the compound starter turns over the V8 lump behind your head, the 327 fires to life with a deafening boom. While the P538 visually embodies all the exotic sensibilities of a ’60s Italian Le Mans challenger, the basso profundo engine note is quintessentially American Muscle, and could just as easily be emitting from a F5000, Can-Am or Trans-Am racecar from the same period.

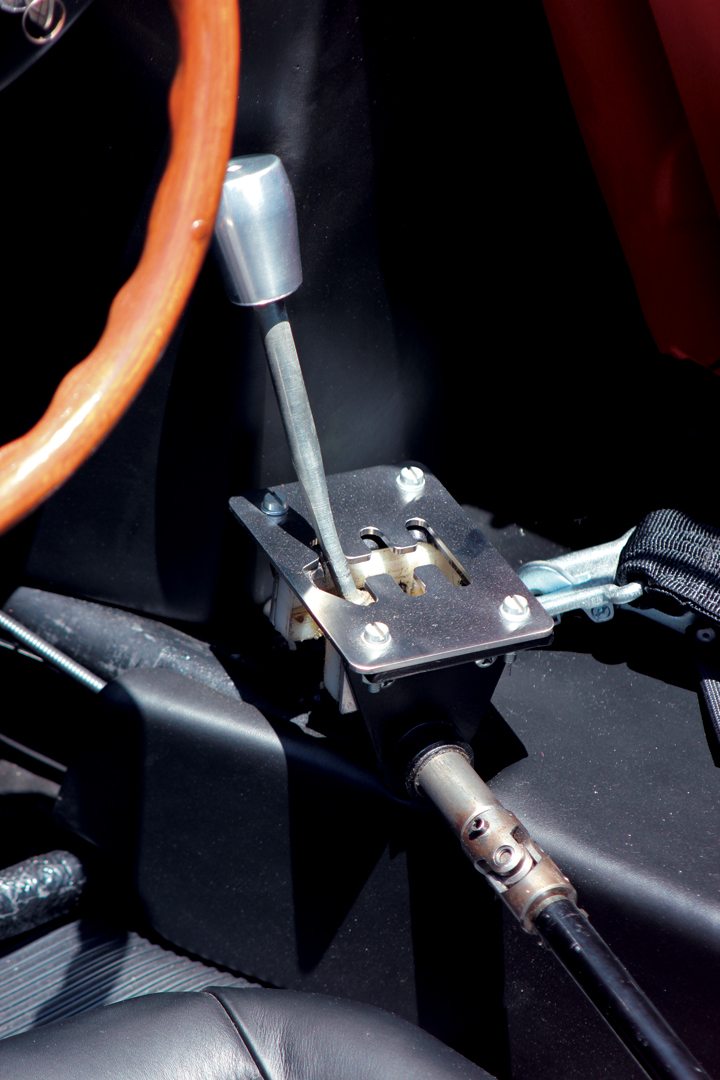

As mentioned earlier, the pedals are very closely spaced together, so one either needs small feet or very narrow shoes to ensure that when you depress the clutch or brake, you are not collecting another pedal in the process. With the clutch in, I select first gear by moving the right-hand shifter into the Ferrari-esque machined shift gate. Surprisingly, the lever goes right into gear without so much as a graunch or hesitation—unlike many purpose-built racecars, the P538 features an all-synchromesh ZF transaxle, which makes gear selection a far easier prospect.

After cracking open the four Webers behind my head and gently releasing the AP racing clutch, the Bizzarrini smoothly pulls away, without any of the shudder or roughness one would expect from a high-horsepower racing car. Once rolling, howeever, snap those eight venturis open and the P538 launches forward with a ferocity one would expect from a 450-hp engine propelling a 1500-lb fiberglass-clothed skeleton. As I work up through the gears, I’m truly surprised by how positive and “civil” the ZF gearbox is. Unlike a Hewland or other dog-ring boxes, the ZF can just be driven without worrying about matching rpms or the necessity of elegant displays of toe-and-heel mastery.

Winding my way up a hillside road, the P538’s handling is very lively and has a tendency to want to dart around a little, when it goes over bumps at high speed. This appears to likely be more an issue of suspension setup, than anything to do with the inherent handling of the car. However, powering through low and medium speed corners, the P538 demonstrates excellent turn-in and feels remarkably solid in the rear as it accelerates through the apex and out the other side.

Hauling the P538 back down from speed is easily handled by the AP Lockheed discs at each corner, though I would have liked to have been able to test these repetitively…from say, 150 or 160 mph, somewhere in France!

In the final analysis, Giotto Bizzarrini fell short in achieving the racing goals that he set for himself in 1966. However, with the P538, he did achieve his overarching goal of building a beautiful and fast sports racer that combined Italian style with a more reliable and powerful engine than the temperamental ones favored by his competitors. As his final encore to these unique racing machines, Bizzarrini’s “Anniversario” is a worthy final chapter to his amazing 50-year career.

The Bizzrrini P538 test driven and featured on these pages (P538*80*2LM/A) will go up for auction August 15-17, at Russo & Steele’s 13th annual Monterey Sports and Muscle sale, at Fisherman’s Wharf.

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis: Steel spacefame

Body: Fiberglass

Wheelbase: 2,500-mm

Track: 1,481-mm (front) & 1,486-mm (rear)

Weight: 1,543 pounds

Steering: Rack & pinion

Suspension: (F) Independent via unequal length A-arms, coil springs, Koni tubular shocks and anti-roll bar. (R) Independent via short and long radius rods, coil springs, Koni tubular shocks and anti-roll bar.

Brakes: AP Lockheed discs, front and rear

Engine: Chevrolet OHV V8

Displacement: 5,359-cc

Bore x Stroke: 101.6-mm x 82.55-mm

Compression : 10.5:1

Induction: 4 Weber 45 DCOE 14 carburetors on Bizzarrini manifold

Power: 450-hp @ 5,400 rpm

Transmission: ZF 5-speed 5DS25 transaxle

Wheels: Campagnolo 6.5 x 15 (f) and 9.5 x 15 (r)

Acknowledgements / Resources

Many thanks to Russo & Steele for facilitating the test drive of this unique racecar.

Goodfellow, Winston

Bizzarrini: A technician devoted to motor racing

Giorgio Nada Editore, 2004,

ISBN:88-7911-317-8

de Hartog, Jack Koobs

Bizzarrini: P538 Anniversario

CCM GmbH, 2011