Words by: Glen Smale. Images by: Virtual Motorpix/Glen Smale

First of all, it would be worthwhile to recognise the significance of the event that took place at Goodwood this last weekend. This year marked the 75th year since Goodwood Motor Circuit opened its doors to the sport back in September 1948. Adding to that important milestone is the fact that this year also marked the 25th running of the now famous Goodwood Revival, the finest and most characterful automotive garden party in all the world.

Then there were the other anniversaries such as the 75th birthday of Lotus, it was also the 100th year since the birth of the legendary Carroll Shelby. In addition, the Fordwater Trophy was this year dedicated to the Porsche 911, marking 60 years since the launch of that evergreen sports car model back in 1963.

Over the years, the Lavant Cup has been dedicated to a variety of different cars such as the D-type Jaguar, and the MG-B, but this year the honour fell to the Ferrari brand, specifically the GT cars that raced between the years 1960 to 1966. As if to recognise the closeness of the action on the track, the weather delivered three of the most glorious warm, sunny and bright days that could be wished for.

Official practice for the Lavant Cup took place on Friday at 11h45 on Friday, followed by the race on Saturday at 14h15. Eighteen cars in all were on the entry list, and a stroll through the paddock revealed pit after pit of the most striking cars from the Maranello brand, with a seemingly constant stream of enthusiastic admirers milling around. There were the inevitable ‘selfies’ being taken, along with proud parents taking innumerable snaps of their offspring standing next the father’s (or mother’s) favourite Ferrari.

Some History

GT racing in the early 1960s was almost the sole domain of Ferrari’s greatest and star-studded family of road and race cars. Starting in the mid-1950s, the 250 GT Competizione (better known as the ‘Tour de France’) set the stage for the GT onslaught from Maranello, and this was followed by the 250 GT SWB in 1959 and the 250 GTO in 1962. This latter model was dominant in competition around the world, but when Enzo Ferrari constructed the 250 LM in 1963 and tried to get it approved as a GT car and successor to the 250 GTO, the FIA would not hear of it. Ferrari argued that it was powered by the same engine, but by moving the engine from the front of the car to behind the driver, in the eyes of the FIA, this made it a different car altogether and it would be considered a new model. The 250 LM was a truly striking mid-engined race car, but the body sported a completely different and new body design.

The FIA was, however, familiar with Ferrari’s tricks. Incensed by the FIA’s attitude, he had to re-engineer the 250 GTO and using some of the design cues from the 250 LM, the beautiful 250 GTO/64 was created. The body of the new GTO/64 was both shorter and lower, but a fraction wider.

As it happened, the 250 LM was a very different machine, too different in fact for the FIA’s liking to be considered as a development of the 250 GTO. It was shorter and significantly lower and lighter than the 250 GTO on which Ferrari had tried to get the new model homologated for the 1963 season. It was powered by a 3.3-litre version of the GTO’s engine, and as a result, with the car’s characteristics and low production numbers, the FIA required this race car to be treated as a new model, forcing it to race as a prototype and not a GT. As it happened, the Ferrari 250 LM would go on to become a very successful racer in its own right.

Giotto Bizzarrini was one of the engineers fired by Ferrari during the ‘palace revolt’ of 1961, and being an engineer of such talent, he was immediately hired by Count Giovanni Volpi. Still seething following his mass firing of employees, Enzo Ferrari stubbornly refused to sell a GTO to Count Volpi. Volpi wanted to compete with a new 250 GTO, as without one he would be at a disadvantage, and so he hired Giotto Bizzarrini and Piero Drogo to modify an older Ferrari 250 GT SWB Competizione so it would be competitive. The result was the distinctive ‘Bread Van’ which is still highly competitive in today’s historic racing circles.

In 1963 Ferrari launched a new GT model, the 330 LMB, also sometimes referred to as the 330 GTO.The 330 LMB used the 250 GTO chassis and body, but it was fitted with the larger 4.0-litreengine as used in the 400 Superamerica. The car was as a result longer and wider, but the much bigger engine was more than capable of handling the added weight.

The Entry List

The Lavant Cup was a 25-minute race for Ferrari GT cars that raced between 1960 and 1966. On the race card were no less than ten 250 SWBs,one250 GTO,a 250 GT Lusso, a 330 LMB and a 250 Drogo, as well as the ever-popular 250 GT SWB ‘Bread Van’.Arguably three of the most muscular looking sports racers of the era, the 250 LM, were to be seen in the paddock, but only one would actually take to the circuit. The No. 26 250 LM of Gary Pearson was not able to take to the track due to an engine issue that the team discovered after practice, and that sadly wasn’t fixable in time for the race.

The Race

Rob Hall was on pole in the No. 526 250 LM with the No. 73 250 GT SWB Competizione of Emanuele Pirro alongside. Despite the 250 LM possessing a significant performance advantage over the older 250 GT SWB, it was Pirro who got away first, and led the 250 LM into Madgwick. It looked as though Pirro might head the field onto the back straight, but Hall was having none of it and quickly regained his number one spot.

Due to a technical infringement the 250 GT SWB ‘Bread Van’ had to start from the back of the grid, but this extremely fast car had a storming start, and was up to seventh by the time the field had all made it through Madgwick on the first lap. It continued to slice its way through the pack and after a couple of laps was lying third.In their eagerness to get a good start, the Nos. 7 and 21 250 GT SWBs were penalised ten seconds each for jumping the gun.

A few laps later, Rob Hall spun out onto the grass to the left in the area of St. Mary’s dip, the back of the car striking the tyre wall a glancing blow. A small amount of oil had been deposited on the track, and the Rob Hall car hit it first, and faster than anyone else. It was an excellent ‘save’ by Hall, and he guided the 250 LMsafely back onto the track almost without losing a breath, but it had slipped down the order and he was now in seventh place. During this time Pirro, always ready to pounce, took the lead in the No. 73 250 GT SWB Competizione, but before Hall’s misdemeanour with the tyre wall could have a lasting effect on the race, he had brought the 250 LM back into contention and soon retook the lead.

On the ninth lap, about half distance, the No. 156 Ferrari 250 GTO of Karun Chandhok suddenly locked up going down the back straight. A huge flame burst from under the car as the £30-million Ferrari performed a 360 degree spin and as Chandhok gathered himself, he somehow managed to control the car by steering it onto the grass, whereupon he exited the car very quickly. By now the flames had subsided but smoke was still coming from under the car, and as the marshals arrived, any remaining fire was quickly doused with an extinguisher. The cause was an engine failure which resulted in a hole in the block, and the escaping oil is what caught fire. Fortunately, the onboard fire extinguisher system did its job, and Chandhok was praised for his quick reactions and for keeping the car out of the way of those competitors following him. He escaped the fiery incident but was mightily disappointed that he couldn’t complete the race, and suffering no more than a melted racing boot, he also very relieved that both he and the car were safe.

There were two further retirements, these being the No. 11 Ferrari 250 GT SWB driven by Ben Cussons and the No. 6 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C of Martin O’Connell which were both out with ‘mechanical’ problems.

While the remainder of the race went off without too much drama, this in no way infers that the racing was processional. Despite the extremely high value of these cars, the drivers did not hold back and drove their steeds with enthusiasm and commitment, sliding around corners and really pushing the cars to their limits. This is of course what the paying public had come to see, their favourite race cars being driven at full chat.

Race Results

Pirro stayed in touch with the lead 250 LM but in reality he was not going to beat the more powerful Ferrari for pace. It came then as no surprise to see Rob Hall cross the line first in the 250 LM, followed closely by Pirro in the No. 73 GT SWB/C, with the No. 16 250 GT SWB ‘Bread Van’ in third place. These top three finishers were separated by just five seconds, but the gap to the fourth place No. 14 GT SWB/C was a further thirteen seconds. To the drivers, winning is everything, but to the spectators, just seeing these prized gladiators on track was everything.

Author’s Note

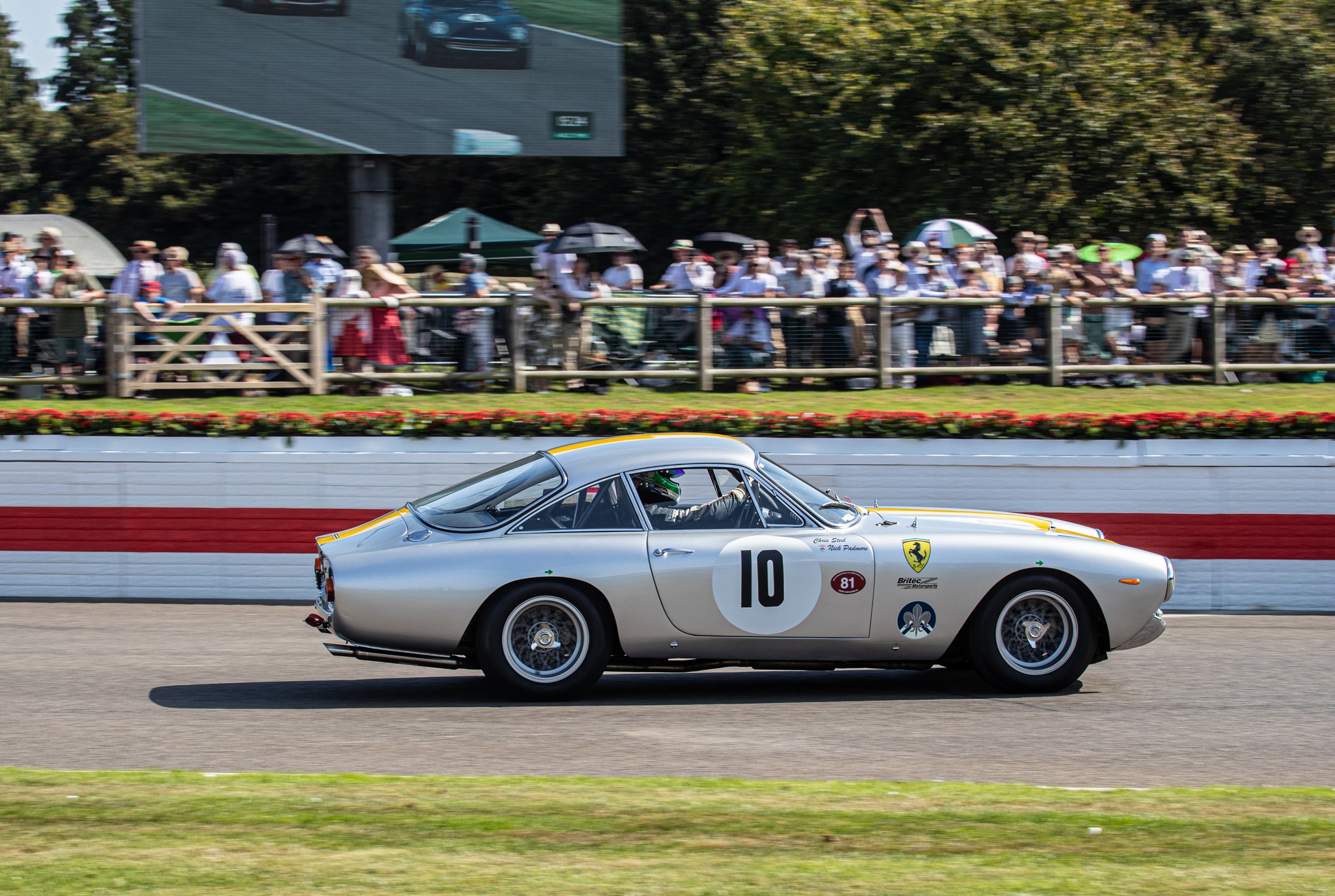

Spectators will have noted three other beautiful Ferraris were languishing in the paddock, that were not entered in the race, these being the red/white No. 8 Ferrari 250 LM, the white No. 10 250 GTO and the familiar red/blue 250 GTO/64.The fact is that none of these three cars were due to race, they were present in order to lead the field on the formation lap.

The first was red/white No. 8 Ferrari 250 LM which is the ex-John Surtees, Jochen Rindt, LorenzoBandini, David Piper, Umberto Maglioli car that, among other results, came second in the 1964Reims 12 Hours in the hands of Surtees/Bandini. The next car was the white No. 10 250 GTO, this car originally being owned by John Coombs and raced in period by a Roy Salvadori, Graham Hill andJack Sears, among others. The third car in this group was the 250 GTO/64 “APB 1” in its familiar red with light blue flashes. This car was in fact the reason why Goodwood held this race, to celebrate 60 years since a Ferrari GT car won at Goodwood for the last time in period, when Graham Hill won the TT back in 1963.