There are three people who you acknowledge as important to the marque when you see a Rolls-Royce. There is Charles Stewart Rolls, Henry Royce, and Eleanor Thornton. Who is Eleanor Thornton, you ask? Well, she is the “Spirit of Ecstasy,” more about that her later, since her significant contribution to “The Best Car in the World” comes a bit later than those of Royce or Rolls.

Royce and Rolls

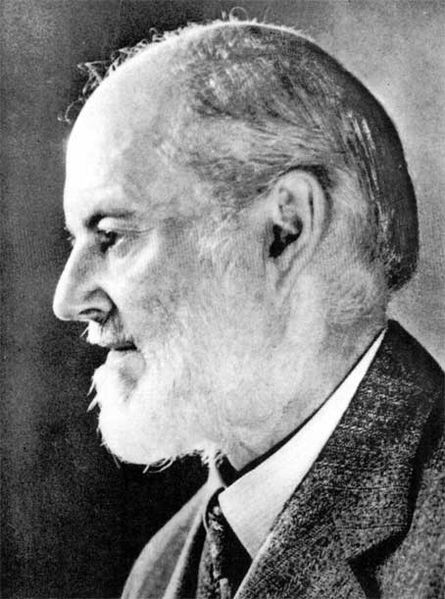

Henry Royce was an engineer who preferred to be called a mechanic. When his father’s flour mill failed, the family moved to London, where Royce, at nine years old, was sent out to make a living. He sold newspapers and delivered telegrams until an aunt paid for him to get an apprenticeship with the Great Northern Railway in 1878. That lasted for three years until his aunt was no longer able to pay the premiums to support his apprenticeship. He then worked for the Electrical Light and Power Company in Liverpool until the company failed. Tired of working for others and with savings of £20, he rented a small workshop in Manchester in 1884 together with his then partner, Ernest Claremont. They were primarily subcontractors for larger companies, making electric filaments and lamp holders. They also made electric doorbells, which were becoming fashionable and provided a nice profit to the company. In 1891, Royce patented a sparkless drum-wound dynamo, providing additional funds and allowing them to get into the business of building electric cranes. They were soon making a variety of lifting equipment, and F.H. Royce & Co. went public in 1894.

Royce’s first automobile was a De Dion-engined quadricycle, then he bought a Decauville automobile. It was powered by a vertical twin engine, which is a design he would later put in his own automobile. According to “The Beaulieu Encyclopedia of the Automobile,” Royce complained of the “terrible unreliability and bad design” of the Decauville. He decided to build his own automobile, but in order not to disturb the main business, he and two apprentices set up in the corner of their factory and developed the first Royce. Like the Decauville, it was powered by a vertical twin engine. The engine design used a two-throw crankshaft to better balance the engine, and the car had a larger “silencer.” Royce was apparently fanatical about the fit and finish of anything that moved, even how the teeth of the gears were formed. That fanaticism together with that silencer, made the Royce a very quiet car. The first production model was finished on April 1, 1904. Only a total of three were built. Royce kept the only two-seater, gave one rear entrance tonneau bodied car to his partner, and sold the other tonneau to Henry Edmunds, who introduced Royce to Rolls in May of that year.

Unlike Royce, Rolls came from a privileged background. His parents were wealthy, and he was educated at Eton and Cambridge, where he received a degree in engineering. He got his first automobile in 1896 when he was 19 years old. It was a 3½ horsepower Peugeot – possibly the first car in Cambridge. The “Encyclopedia” reports on a 180-mile Christmas trip he took from London to Monmouthshire: “A less adventurous soul would have left the car in London for the vacation, or put it on a train, but Rolls thought that cars were for driving, and although the journey took him two days, including many hours spent working on it by the roadside, he arrived in time for the family’s Christmas celebration.”

It didn’t take long for him to start racing. He raced a Panhard in 1899 and finished second in the Paris-Ostend race and fifth in the Paris-Boulogne. He received a gold medal in 1900 in the Thousand Mile Trial and was 18th the next year driving a Mors in the Paris to Berlin race. His father set him up in business in 1902 importing and selling a variety of cars, including Panhard, Mors, Minerva, and Gardner-Serpollet, as well as commercial vehicles. Rolls had heard about the Royce cars, but he was initially unimpressed.

Henry Edmunds, who had one of the three Royce cars, persuaded Rolls to visit Royce’s factory. Rolls was apparently impressed with the car’s silence and smoothness, so he proposed to take all of Royce’s production with a couple of conditions. The first was that four- and six-cylinder engines should be developed. The other condition was that Rolls name would be added to the name of the automobile – Rolls-Royce was born.

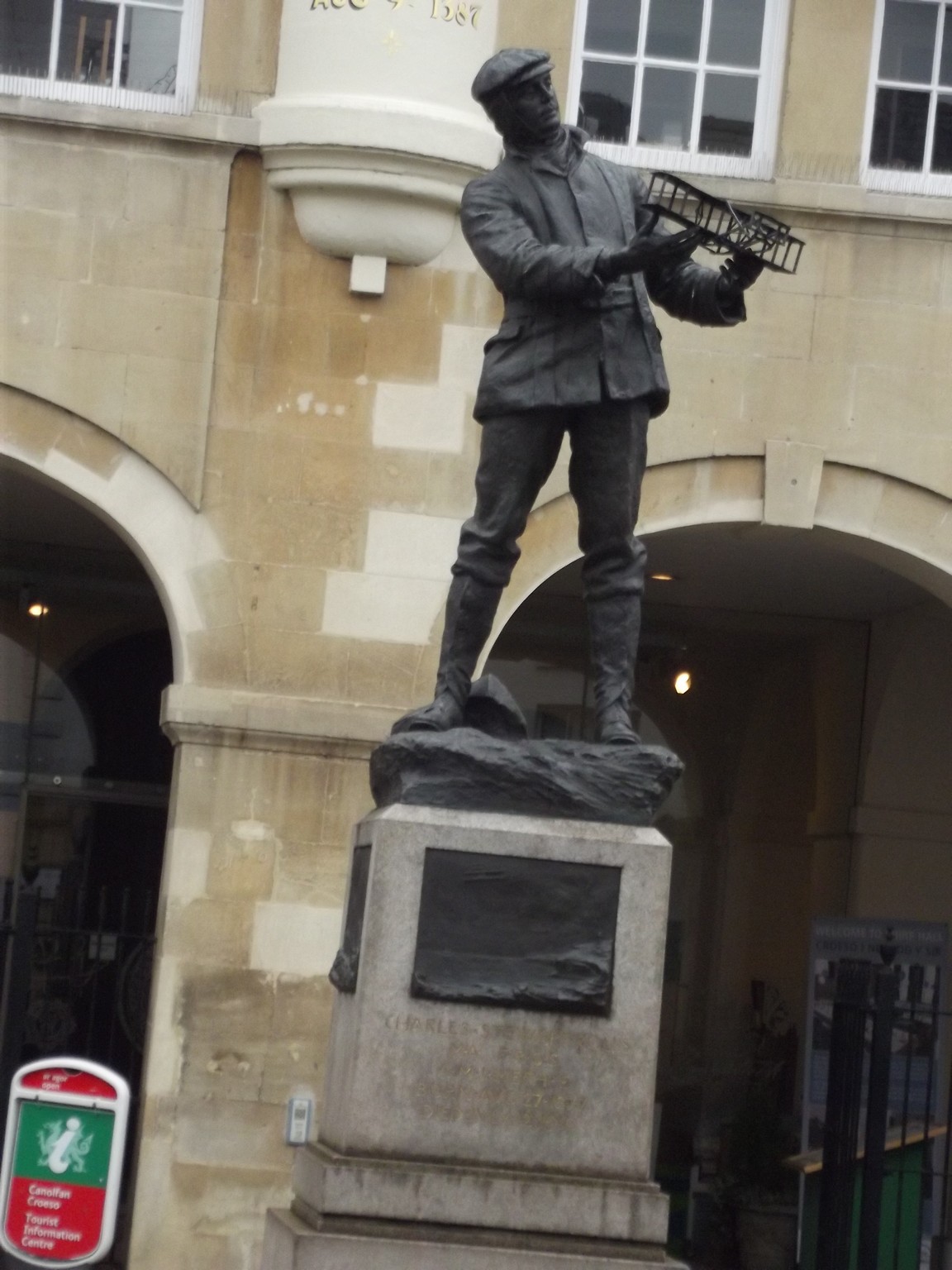

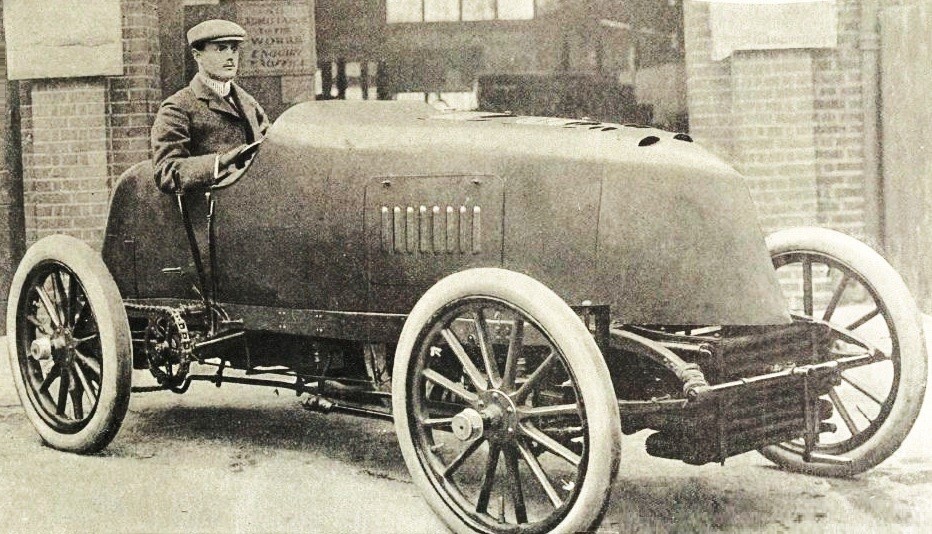

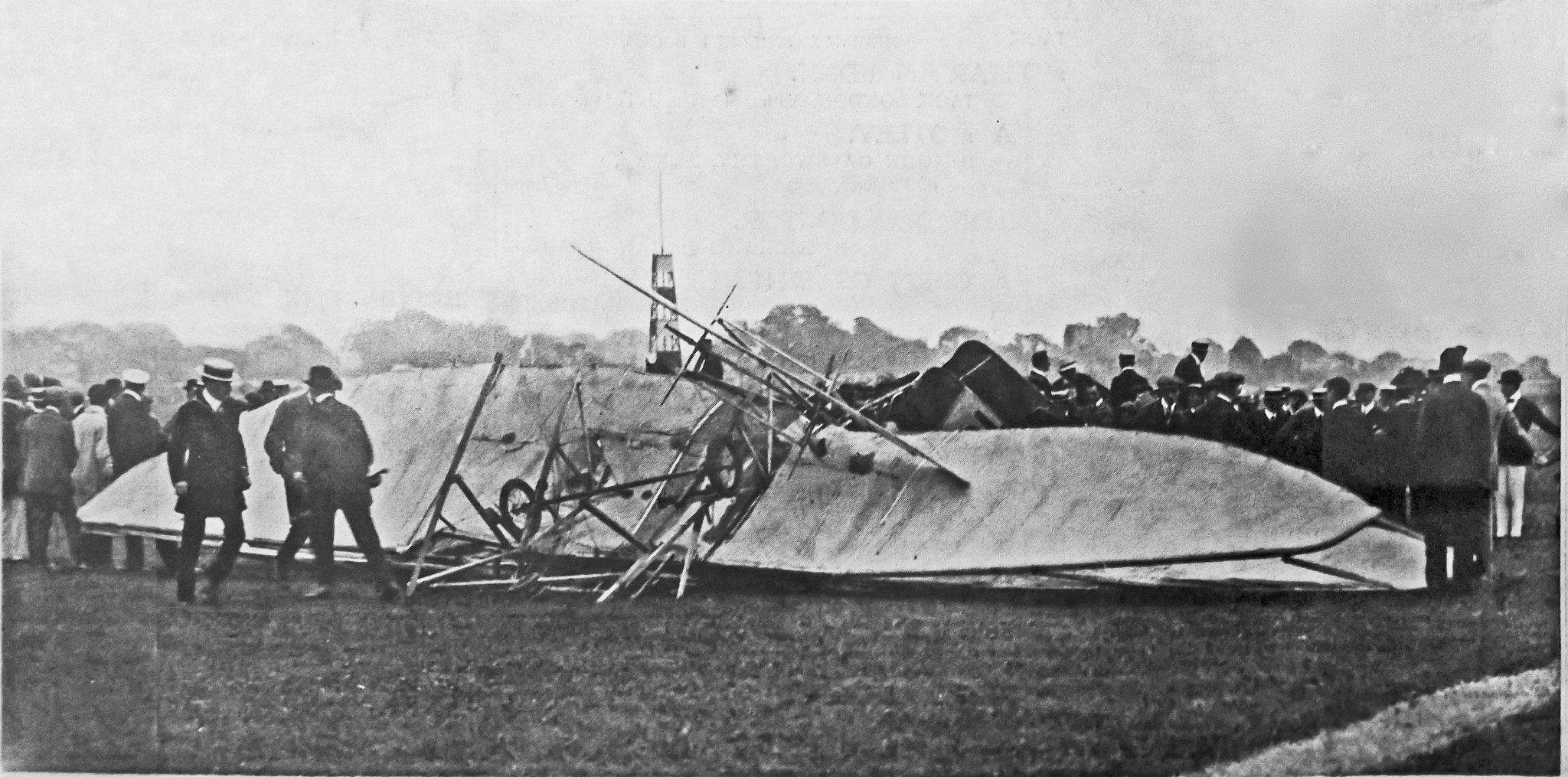

Rolls concentrated on selling the cars, but he also raced them, including a 20 hp in the Tourist Trophy in 1905 and 1906, when he won. Royce was less enthusiastic about racing and saw the future of Rolls-Royce in the “Dutchess trade,” emphasizing smooth, silent cars. By 1906, Rolls had a new fascination – aviation. First it was with balloons, then he bought a Wright Flyer. Rolls resigned from Rolls-Royce Ltd. in April 1910 and took on a role as a technical advisor. Sadly, on July 12, 1910, Rolls crashed his plane and was killed. Royce, who was a workaholic, ignored his health and became gravely ill. In 1912, he was given three months to live. He continued to work from home, where he supervised the design of several more Rolls-Royce models as well as aero engines. He lived until 1933.

Spirit of Ecstasy

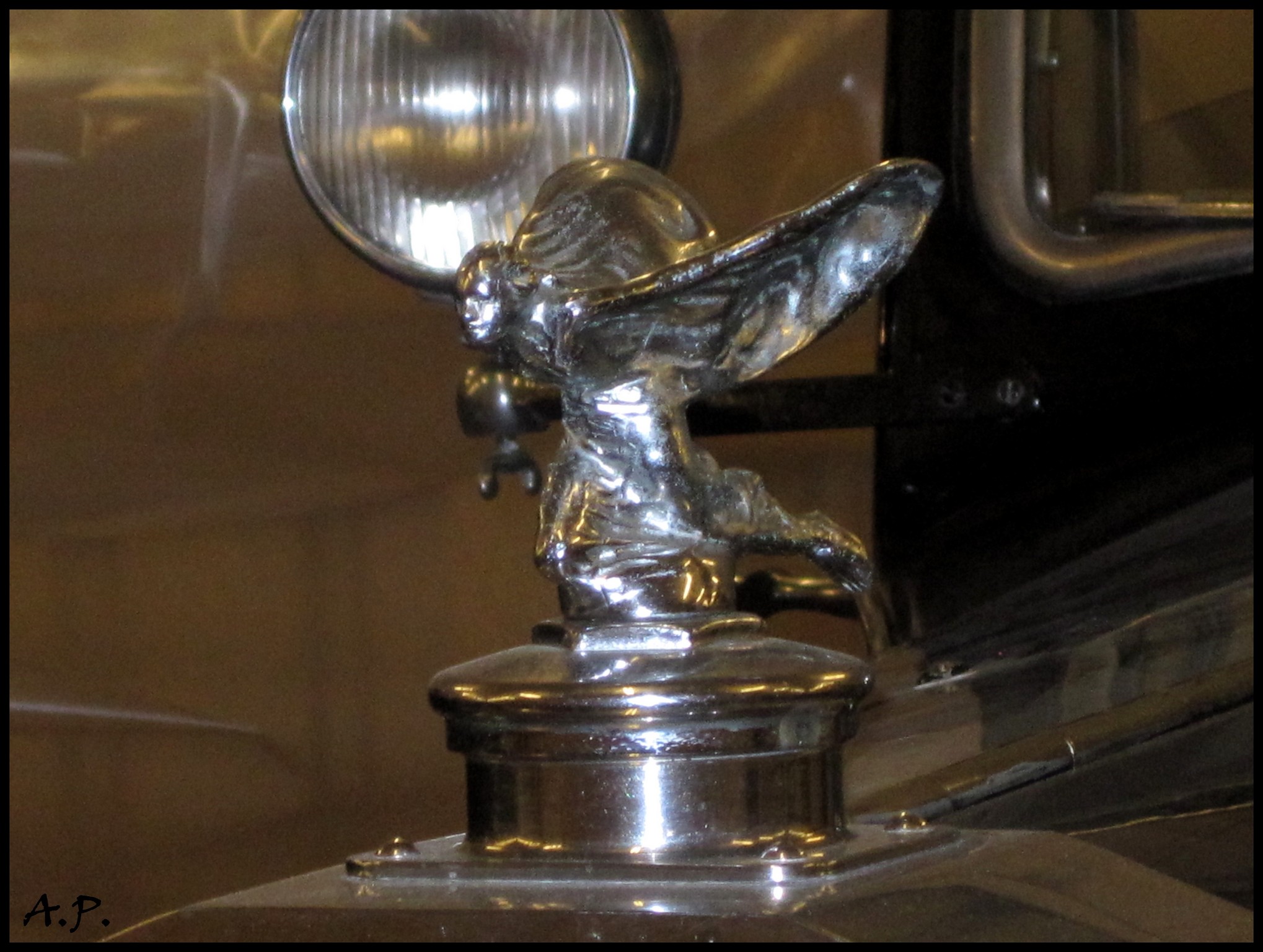

Eleanor Thornton’s involvement with Rolls-Royce came about because of her boss’ fascination with the autos. Her boss was John Walter Edward Scott-Montagu, Second Baron Montagu of Beaulieu. His son, Edward John Barrington Scott-Montague, Third Baron Montagu of Beaulieu, wrote in Automobile Quarterly, Volume V, No. 1 in an article titled “Spirit of the Flying Lady,” that, “. . . behind the story of the ‘Spirit of Ecstasy,’ as the flying-lady mascot was called, lies a series of links, involving a pioneer automobilist and the secretary who was his closest friend and companion, a sculptor of distinction who contrived to cross the bridge to commercial success without sacrificing[,] and the celebrated partnership, forged in Manchester in 1904, that led to the evolution of ‘The Best Car in the World.” Speaking of Ms. Thornton, Edward Scott-Montagu said, “She was. In fact, very much more than a secretary, but throughout her long association with John Scott-Montagu she acted with consummate dignity….”

The Second Lord Montagu and C.S. Rolls were the first British drivers to race on the European Continent in the Paris to Ostend race in 1899. Lord Montagu was an ardent supporter of automobiles, encouraging Parliament to approve the first motor race in Britain, pushing through the first bill to register motor vehicles, and arguing for better roads. He was a friend of Rolls, a fellow Etonian, and “he performed the opening ceremony at the Rolls-Royce’s new Derby plant in July 1908.” His son said, “. . . henceforth there was always at least one Rolls-Royce in the garages at Beaulieu.”

The earliest Rolls-Royce cars had no mascot. Lord Montagu wanted an elegant mascot for his Rolls, so he commissioned Charles Sykes, a well-known sculptor, to create one. His creation was called “Whisper,” and it would adorn all of Lord Montagu’s Rolls-Royces. When “Whisper” was rejected as the mascot for all Rolls-Royces, Sykes designed the “Spirit of Ecstasy,” describing her as a girl who “has selected road travel as her supreme delight and has aligned on the prow of a Rolls-Royce car to revel in the freshness of the air and the musical sound of her fluttering draperies.”

In his article, Edward Scott-Montagu notes that there may have been more than one model for the “Spirit of Ecstasy,” but the “features are unmistakenly those of Eleanor Thornton.” Sadly, Ms. Thornton’s life was cut short. In 1915, voyaging with John Scott-Montagu from London to India, the “S.S. Persia” was torpedoed by a German U-boat. Both were sucked under by the sinking ship, but an explosion propelled him to the surface. Only eleven survived. In a tribute to Thornton, Edward Scott-Montagu said, the “Spirit of Ecstasy” is “a fitting tribute to a girl who bought efficiency into my father’s professional life and serenity into his private life, and she handled an equivocal situation with dignity.”

Rolls-Royce

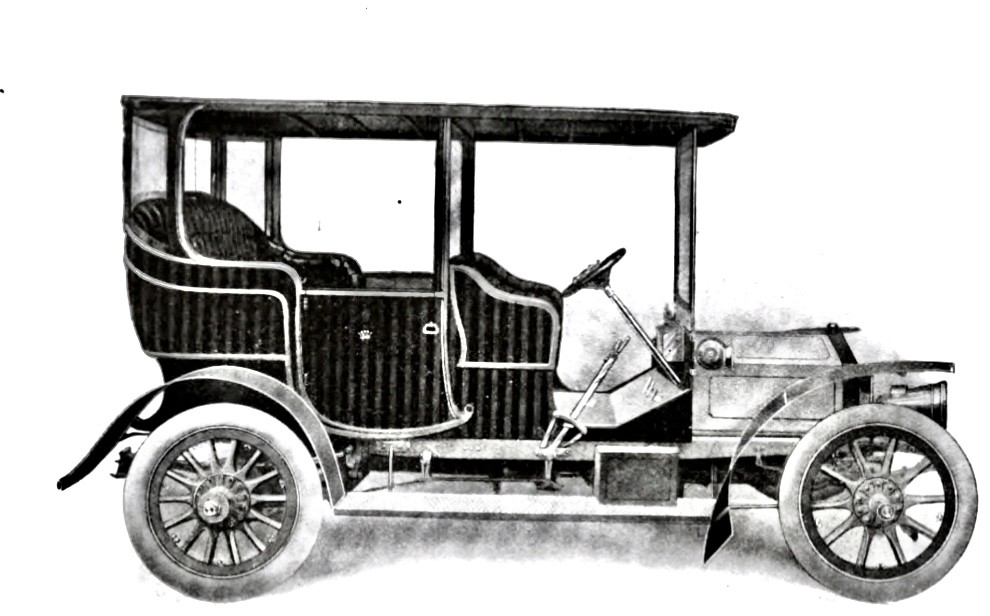

The first car badged as a Rolls-Royce was shown at the Paris Salon in December 1904. It was much like its Royce predecessor, having a vertical twin engine displacing 1809 cc. It had a redesigned crankshaft and a much-improved external finish. According to the “Beaulieu Encyclopedia of the Automobile,” “the flat-topped radiator of the Royce was replaced by a Grecian design not unlike the Parthenon in proportions, which has been carried by every Rolls-Royce since 1904.” Of an intended production run of 20 cars, only sixteen were built through 1906, when Rolls again pressed for the cars to be more luxurious and to include four and six-cylinder engines. In the company catalog for 1905, there were three engines on offer – three-cylinder, four-cylinder, and six-cylinder. They were available as rolling chassis only, with Barker & Co. the recommended coachbuilder. Each of the engines had the same cylinder dimensions to simplify production. The cylinders were cast in pairs, so the four-cylinder had two pairs of cylinders, and the six-cylinder had three pairs. The three-cylinder was the odd one. Each of its cylinders were cast separately, making it a difficult engine to produce alongside the others. Apparently, Royce realized that it was much more efficient to produce two similar engines, and the three-cylinder was dropped after only six were produced.

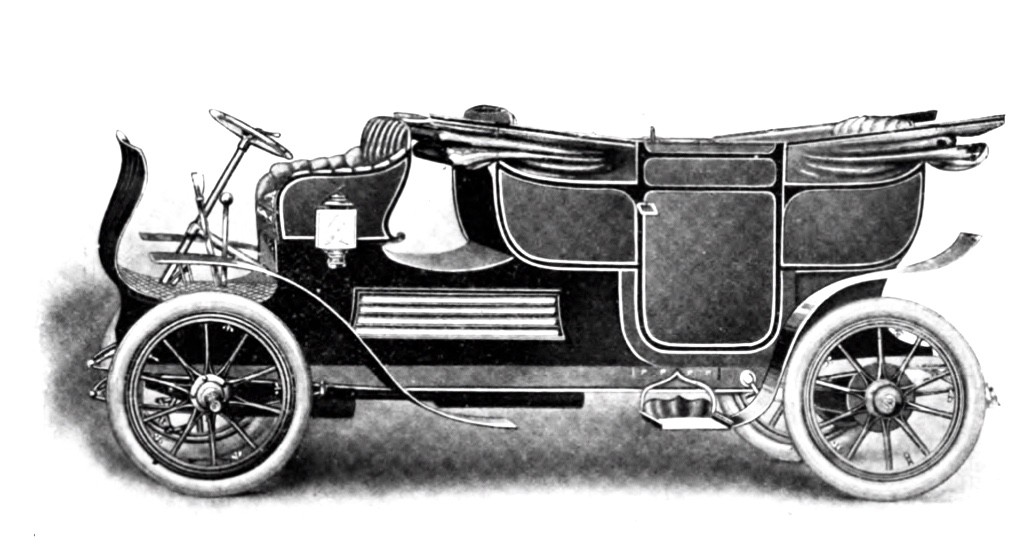

The four-cylinder was the most popular model, with forty sold between 1905 and 1908. It had an honest 20 bhp and was the only Rolls-Royce that has a significant motorsports history. Two Tourers with a lightened four-speed transmission were entered in the Tourist Trophy in 1905. Although the car driven by Rolls failed to finish, the other, driven by Percy Northy finished second. The following year, Rolls won the Tourist Trophy in a car with wire wheels and won again later that year at Yonkers, New York.

Not all developments were successful, though. There was “Royce’s brief flirtation with folly,” which is what the first V8 engine ever developed from scratch was called. It was a wide angle V8 displacing 3535 cc. Two were built with the engine located below the passenger side of the car. A third was front-engined with a very low bonnet. “This was ordered by the newspaper tycoon Lord Northcliffe who called it ‘Legalimit,’ as it could not exceed 20 mph, which was the speed limit in force in Britain.” None of these cars survive.

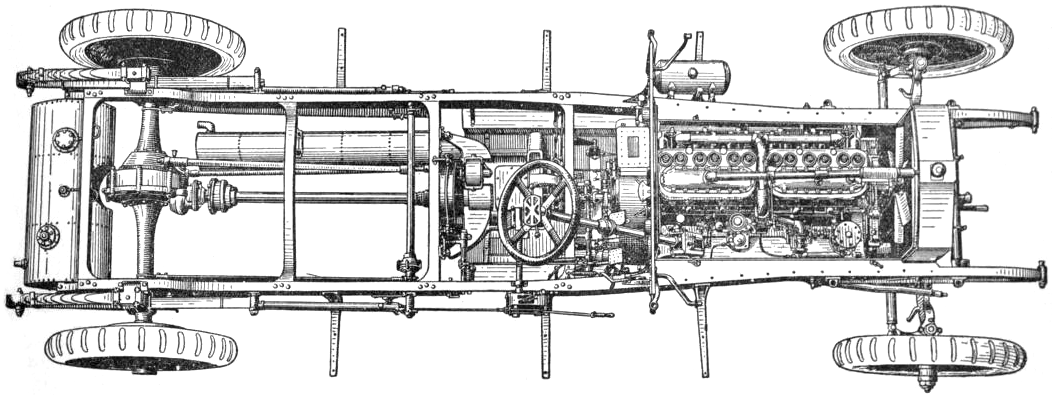

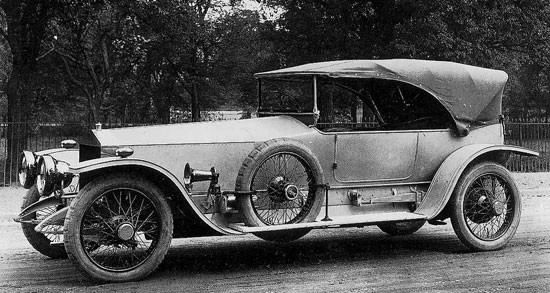

Rolls-Royce developed a new six-cylinder car for 1907. There had been a problem with torsional vibrations in the crankshaft of their previous six-cylinder engines, so the engine design was changed to two blocks of three cylinders cast together instead of the previous three blocks of two cylinders. The engine’s initial displacement of 6177 cc was raised to 7036 cc, producing an estimated 48 bhp, so it received the designation of a 40/50. That lasted until the thirteenth model was built. It received a Barker body painted silver with silver fittings. It became known as the “Silver Ghost,” a name that was subsequently given to all Rolls-Royce 40/50 cars.

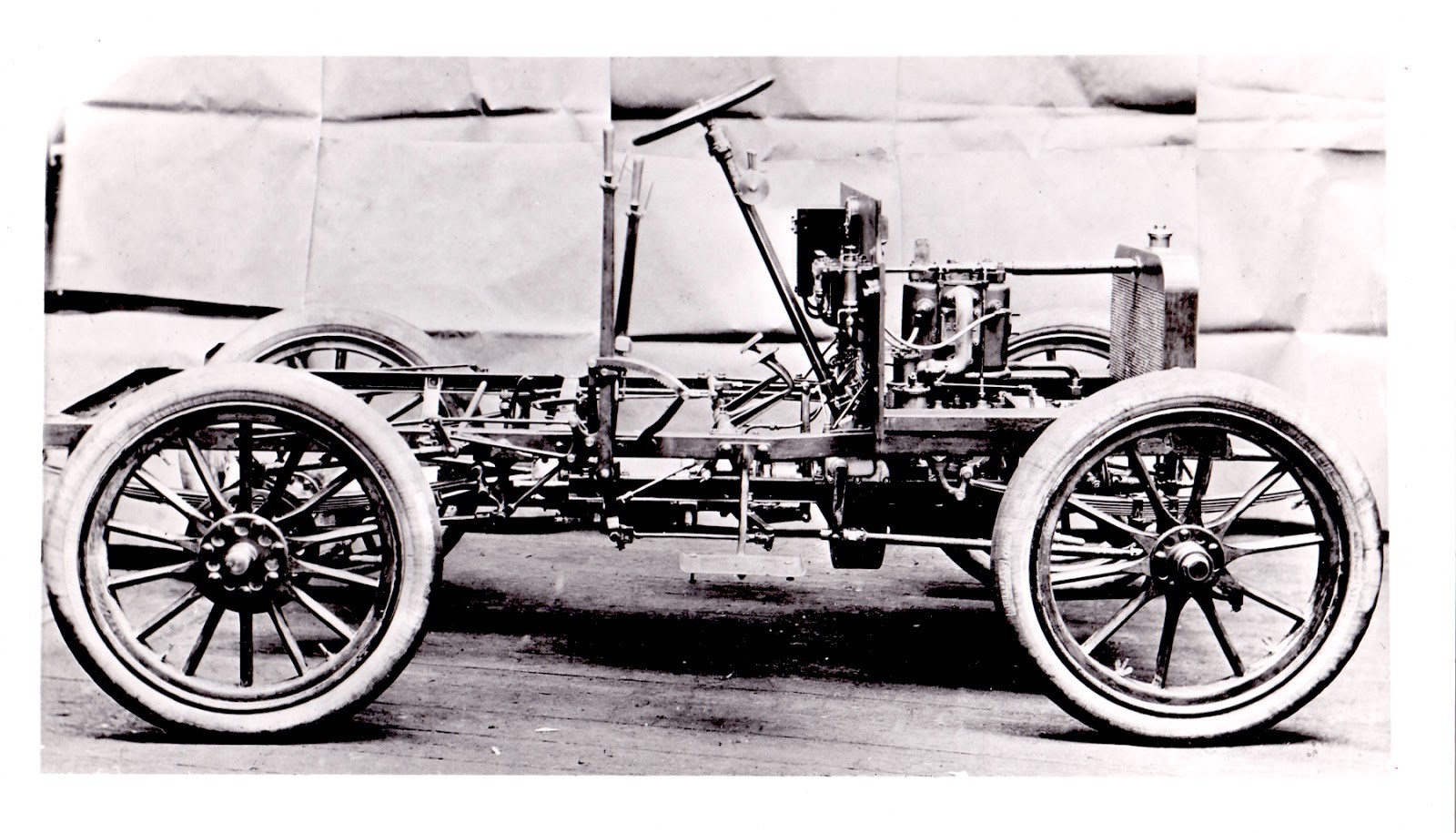

Photo 15a – A detailed look at the chassis and engine of the 1910 Rolls-Royce. Notice the two banks of three cylinders making up the six-cylinder engine.

An early 40/50 model was tested extensively. It ran 2000 miles over the course of the Scottish Reliability Trial, then ran the actual Trial, where it received a Gold Medal. It then ran continuously between London and Glasgow until it had driven 15,000 miles. The Silver Ghost became so popular that the earlier four-cylinder car was dropped, and Rolls-Royce made the decision to concentrate on one model at a time. Production at four per week was not keeping up with demand, so the company moved their production to Derby in 1908, where production increased to seven per week, a production level that continued until the beginning of World War I.

There were few changes in the Silver Ghost. Displacement was increased to 7428 cc in 1909, and there were a couple changes in the transmission. Various bodies were put on the four wheelbases that were produced, including tourers, laudaulets, and limousines. A few two-seaters were produced, including one that Rolls used to transport his balloon. Two specials were built. The London-Edinburgh Tourer reached a top speed of 101.8 mph at Brooklands, and the Alpine-Eagle dominated the 1913 Austrian Alpine Trials, winning the Archduke Leopold Cup and six other awards.

During the war, Rolls-Royce built staff cars, supply vehicles, and armored cars. Silver Ghost production resumed in 1919, and demand greatly exceeded supply, resulting in inflated prices for both new and used cars. There were some improvements to the Silver Ghost, including electric lights and starter soon after the war and four-wheel brakes in 1924. Rolls-Royce built all parts for their cars except for the tires and bodies. Silver Ghosts were also made in Springfield, Massachusetts, from 1921 to 1926. But the Silver Ghost’s time was over, and it was replaced by the Phantom in May 1925. The Phantom was the new 40/50 but with and overhead valve engine. It was, however, not the lone model being produced by Rolls-Royce. Sales were suffering from inflation and increased taxes, putting the cars out of reach for the less wealthy. Realizing that the company was facing a difficult future, Claude Johnson, Royce’s partner, suggested a smaller, less expensive car that could be driven without a chauffeur. The result was the Rolls-Royce Twenty. It was powered by a 3127 cc six-cylinder overhead valve monobloc engine with a detachable head. It had a coil ignition rather than a magneto, and the shift lever was in the center of the car. Other Rolls-Royces would continue to have the shifter on the right until 1949. Thanks to the Twenty and a strong market for their aero engines, Rolls-Royce survived the Depression when many other high-end manufacturers did not.

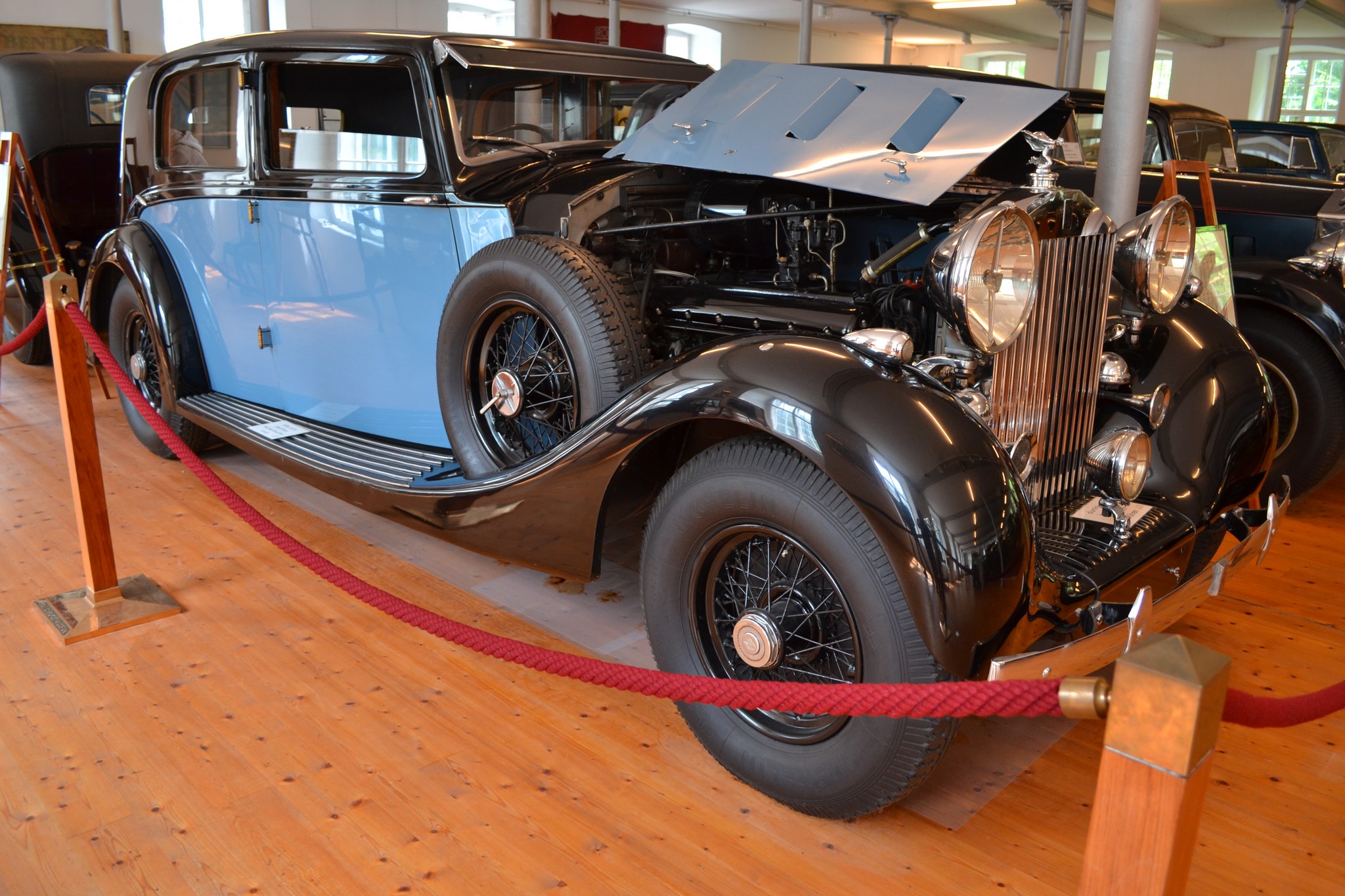

The Phantoms evolved during the 1920s and 1930s. The original became the Phantom II when it got a bit more displacement and horsepower, probably around 100 bhp in 1929, but that is only an estimate since the company does not reveal how much power the cars produce – they only say that the power is “adequate.” The Phantom II got a new chassis and a redesigned cylinder head, producing another increase in power. After Royce died in 1933, the Phantom III was designed by A.G. Elliott and Ernest Hives in 1935. It had a very complex V12 for power.

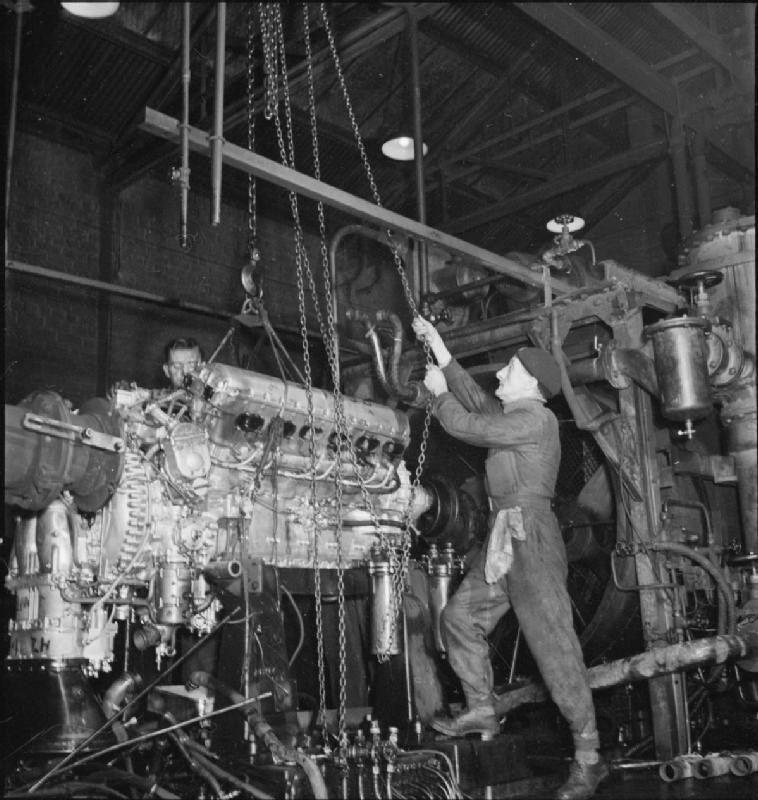

In 1938, the company built a new plant to produce aero engines in Crewe. Those engines, especially the 27-liter V12 Merlin would become their emphasis during World War II. Merlin engines, produced both by Rolls-Royce, Ford, and Packard, would power two of the best fighter aircraft in the war, the Supermarine Spitfire and the North American P-51 Mustang. After the war, automobile production was moved to Crewe and aero engine production continued at Derby.

After WWII, Rolls-Royce first offered the Silver Wraith, which it built until 1959. It got a longer wheelbase in 1951, and, in 1953, a General Motors-type automatic transmission was offered as an option. Its six-cylinder engine had a displacement of 4887 cc and was subsequently used on the early Silver Cloud. Rolls-Royce also offered a Silver Dawn, with steel bodywork rather than aluminum on ash, for export only beginning in 1949.

Phantoms, continued to be built until 1950. They were powered by an inline eight-cylinder engine, but the Phantom IV was built in a very limited series of only 17 cars, all intended for Royals and other special customers. Owners included the Duke of Edinburgh, Princess Elizabeth, the Shah of Iran, Aga Khan, and General Franco.

The Silver Cloud had a pressed steel body by Rolls-Royce, although it could be had as a chassis only to be bodied by Freestone & Webb, Hooper, or H.J. Mulliner. The automatic transmission was standard in the Silver Cloud, although power steering was still an option. The Silver Cloud II was introduced in 1959 and had a 6230 cc light-alloy V8 engine that could propel the car to a top speed of 115 mph. The engine is said to have been inspired by the 1949 Cadillac overhead valve V8, a claim that Rolls-Royce denies. The Silver Cloud III of 1963 looked much like its predecessor except for having four headlights, which many longtime Rolls-Royce customers thought were inappropriate. The Silver Clouds were replaced by the Silver Shadow, a model with more up-to-date engineering but with less presence than the cars that preceded it.

Graham’s 1960 Silver Cloud II

Graham Messer is a car guy. He has a very diverse collection of interesting automobiles. His cars vary from an exquisite Jaguar XK-150 drophead to a great ‘60s Lincoln Continental convertible with those sexy rear suicide doors. Then there’s the Jensen Interceptor and his wife’s TR6, well, you get the idea. There will be more profiles of his cool cars, but my interest was spiked when I saw his Rolls Royce Silver Cloud II. It was the first successful Rolls-Royce with a V8 engine, but who, of a certain age, can forget the Grey Poupon ads featuring a Silver Cloud like his. That just ads to the story, and a little extra story is nice to have when profiling a car. There are even videos of the Grey Poupon commercials like this one, Grey Poupon – Original Commercial – Bing video, and a sillier one here, pub Rolls-Royce grey poupon moutarde dijon – Bing video.

Messer knew of a doctor who had a pretty decent collection in south Florida. The doctor had homes in both Michigan and Florida. “He sold his house in Florida to move back to Michigan to be near family, and he didn’t have space for all his cars.” Messer bought his Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud II and had it shipped to Tennessee. It needed a tune up and some minor work, but it was a nice car. He has not had to do much to it. It is a UK built car, so it’s right-hand-drive.

When asked what it is like to drive, he answered “It drives phenomenally well. One of their big advertising slogans was that it was so quiet that the only sound you’ll hear is the sound of the clock ticking.” His wife, Rosie Dahl Messer, said it is wonderful to ride in, “You can’t help feeling like royalty. It’s always fun to go downtown for dinner.”

The Silver Cloud is a big, heavy car. Its hydraulic brakes won’t stop it on a dine, but the brakes are good. The driving experience is perfect, although Messer mentioned that right-hand-drive is different, something you need to get used to. It is a comfortable car both to drive and ride in.. It was designed for the owner-driver, although it could certainly be chauffer driven, and the tray tables and mirrors in the back are indicative of that. It was a car that was popular with celebrities. John Lennon had one with a somewhat untraditional paint job. If luxury is what you want in an automobile, Rolls-Royce is the best, and the Silver Cloud has a presence that is hard to beat.

1960 Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud II Specifications

- Body Style: Standard Saloon

- Engine: Spark ignition, four-stroke overhead valve 90º V8

- Engine Manufacturer: Rolls-Royce Bentley L410 series

- Displacement: 6231 cc/380.2 cid

- Bore/Stroke: 104.14 mm (4.1 inches)/91.44 mm (3.6 inches

- Compression Ratio: 8:1

- Horsepower: “Adequate”

- Torque: “Adequate”

- Transmission: “GM Hydra-Matic”

- Carburetion: Two SU HD6 carburetors

- Traction: Rear wheel drive

- Length: 5486 mm/216 inches

- Width: 1889 mm/74.75 inches

- Height: 1626 mm/64 inches

- Wheelbase: 3226 mm/127 inches

- Front Track: 1486 mm/58.5 inches

- Rear Track: 1524 mm/60 inches

- Weight: 2200 kg/4250 lbs