When you look at any listing of Lotus competition cars built from the first Lotus VI of 1952 through to the mid-1970s, you can observe a change in direction. Prior to the ’70s, any listing will show quite a number of models built, including those for the smaller capacity formulae. Closer inspection will also show that Lotus Components was not only in the field of building competition cars, but the company itself was in competition with the likes of Brabham, Merlyn, Tecno and Chevron for a slice of the production racing car market. For instance, the Lotus 61 and 61M were built strictly for Formula Ford, with 248 built. A staggering number when you think of it.

The early 1970s was a time when Colin Chapman withdrew from the production racecar market to focus more fully on the more profitable roadcar side of the business, as well as maintaining the Lotus position within the heady world of Formula One. Looking at contemporary reports it’s clear that there were many players in the market and buyers could at best be labelled as fickle, those who would not necessarily stay with one marque. It was also the beginnings of litigious days, and there was concern that owners might seek some form of recompense as a result of an accident.

The last Lotus competition models that could be classified as “production” cars were the Lotus 69 and 70. Built as the Lotus entry into Formula 5000, history tells us that the 70 wasn’t the most successful of Lotus open-wheelers, as only seven were built.

Formula 2 Progression

The first foray by Lotus into Formula Two was with the Lotus 12 of 1957 that, like many competition cars, actually served multiple purposes. Depending on what engine was fitted, it could perform service in both F2 and F1. The new F2 for 1957, was for un-supercharged engines of 1,500-cc capacity, which suited the Coventry Climax FPF engine of 1,475-cc. For F1, it ran an FPF engine of either 1,960-cc or 2,207-cc.

Chapman capitalized on the success of the Lotus 12 by following it in 1958 with the 16. Featuring an aerodynamic design by Frank Costin, it was indeed a sleek styling exercise, seen by many as a “Mini Vanwall.” However, right from the start there were problems with the chassis tubes cracking, as well as the thin 22-gauge alloy bodywork doing likewise. Like its predecessor, the Lotus 16 was used in both Formula Two and Formula One trim, but while it was certainly a pretty car, history tells us that it was not a success.

While Chapman was struggling with DNF after DNF, the Cooper Car Company was enjoying success after success with its rear-engined cars, to such an extent that during the 1959 F1 season a Cooper received the checkered flag on five occasions, culminating in Jack Brabham winning the World Championship in a works entry.

Chapman followed Cooper’s lead with the new Lotus 18, as both BRM and Ferrari also produced new rear-engined models.

Like the 12 and 16 before it, the Lotus 18 was also multi-purpose, suited for both F1 and F2, but it could also be fitted with a sub-1-liter engine and run as a Formula Junior. The 18 first took to a circuit in anger on Boxing Day 1959 at Brands Hatch, in Formula Junior form. It was, though, the Lotus 18 that would give Chapman his first F1 win at Goodwood on Easter Monday with Innes Ireland at the wheel.

Remember, the Lotus 18 was a model that could be purchased by any motor racing enthusiast, providing they had the right amount of money. For instance, Rob Walker bought one for Stirling Moss to drive. In total, during 1960 and ’61, Lotus Components built a total of 25 Lotus 18s, of which 19 were sold to customers.

It wasn’t until 1964 that Lotus would build another F2-designated car to comply with the new capacity limit of 1,000-cc, un-supercharged. With seven wins from a possible 18, the monocoque Lotus 32 proved to be a success, especially for the Ron Harris team with such drivers as Jim Clark, Peter Arundell and Mike Spence. One 32, fitted with a 2.5-liter Climax engine, was shipped south for the 1965 Tasman Championship, and with Clark at the wheel won four of the seven races in the series.

The following year brought the development of the Lotus 35, which was an evolution of the 32, but unlike its predecessor the new model could be fitted with a range of engines so that it could run in F2, F3 and Formula B in the U.S. In Europe, the works F2 and F3 cars were run by Ron Dennis, with Willment fielding another team.

Waning

During the mid-1960s Chapman’s enthusiasm for building customer cars waned, and with just three Lotus 44 F2 cars built in 1966 it looks as if he kept his cards close to his chest. All three cars were run by Ron Dennis as Team Lotus.

The same applied to the following Formula Two car, the Lotus 48 that was built entirely for use by Team Lotus, hence just four were built. Powered by the Ford-based Cosworth FVA with a capacity of 1,599-cc, the car would win just four races in 1967. The Lotus 48 is a model with some notoriety, as Jim Clark was driving one when he lost his life in April 1968.

Like a racing chameleon, the Lotus 59, launched in 1969, was another spaceframe model that, while built in relatively small numbers, was adaptable to be fitted with a number of engines and therefore could be run in F2, F3 and Formula Ford. The works team came under the Winkelmann banner, and with Jochen Rindt or Graham Hill behind the wheel achieved a total of five wins. However, it was in F3 guise and driven by a young Brazilian named Emerson Fittipaldi that it was most successful, winning that year’s Lombank Formula Three Championship.

Bag-Type Fuel Tanks

The start of the ’70s brought a major change for F2. While engine capacity had remained at 1,600-cc since 1967, as with F1 cars, bag-type fuel tanks became compulsory. This, of course, meant major changes to previous designs.

So was born the Lotus 69, which was a redesign of the 59 from the previous year. Gone was the total space frame chassis, replaced with a center monocoque containing the fuel bags, which resulted in a rounder, almost bulbous styling. Space frame sections were fitted fore and aft of the monocoque.

While the mid-bodywork of the 69 was bulbous, the frontal treatment followed the trends of the period, being wedge-shaped and incorporating a lower intake for the front-mounted radiator.

As mentioned, engine capacity remained at 1,600-cc, which for Lotus meant the Cosworth FVA, based on the Ford Cortina cylinder block incorporating an alloy cylinder head fitted with four valves per cylinder and gear-driven double overhead camshafts. Fitted with Lucas fuel injection the engine produced more than 200 bhp. As with the 59, the gearbox of choice for the Lotus 69 was the Hewland FT200.

Unfortunately for Roy Winkelmann most of his team had jumped ship to join March, so he withdrew from racing altogether, leaving Lotus itself without a showcase. Thankfully, up jumped Jochen Rindt, who formed Jochen Rindt Racing Ltd. with the express purpose of running a team of Lotus 69s. Managed by Bernie Ecclestone, it included such drivers as Rindt (of course) as well as Graham Hill and John Miles.

Emerson Fittipaldi also raced a 69, initially for Jim Russell but later a car entered by Lotus Components itself. History tells us that while Rindt did achieve some success, the Lotus 69 was very much overshadowed by cars carrying Brabham and Tecno badges.

Sadly, with Rindt’s death at Monza in 1970, Jochen Rindt Racing Ltd. didn’t achieve the hoped for success. Subsequently, in 1971, the team was taken over by International Racing Associates, but financial problems meant its life was short. By that stage Lotus Components had morphed into Lotus Racing, but that too was also destined for a short life.

Fittipaldi, on the other hand, had considerable success with his Lotus 69, winning races both in Europe and South America. For 1972, engine capacity for F2 cars was increased to 2,000-cc and with sponsorship from Moonraker Power Yachts (interestingly also controlled by Colin Chapman) the Brazilian continued his European success.

The Lotus 69 was also built to comply with Formula Three and U.S. Formula B, with changes to the chassis including stressed alloy sheet boxes holding the fuel, while another version, called the 69F, was built as a Formula Ford.

Counting all types of the Lotus 69, a total of 57 were built, but as previously mentioned this model, along with the 70, was the last customer car built by Lotus.

Lotus Racing East

Fred Stevenson worked in the automotive sales industry on the East Coast of the U.S., but for our purposes was one of the more prominent Lotus drivers of the period. He had started racing with a Lotus 18 at Lime Rock in April 1965, and would go on to be the East Coast importer and distributor of both Lotus cars and components under the name Lotus Racing East. During his association with Lotus cars, he also ran a 26R Elan and a 47.

In 1970, Stevenson concluded a deal with Mike Warner, the director of Lotus Components, to campaign two Lotus 69s in the U.S. One was to be a Formula Ford, with the second configured for Formula B. It was Stevenson’s opinion, and surely that of Lotus, that the manufacturer’s image in the U.S. was waning. The obvious intent, of course, was to increase sales for 1971 and beyond.

Stevenson’s arrangement with Lotus was that he was to receive preferential treatment with respect to technical and engineering advancements throughout the season. In addition, the cars were to be supplied on a deferred payment arrangement, but when the cars were sold on, Lotus Racing East would pay Lotus Components a fee. In other words, Stevenson’s racing efforts for 1971 would be seen as an official “factory-sponsored” effort.

Along with the Formula Ford-configured car, Lotus 69 FB 71/69/6 duly arrived in the U.S. during the spring of 1971. Initially, it was fitted with a Hart TC 71138 engine, Hewland FT200 gearbox and Firestone tires.

It was Stevenson’s goal to campaign the cars in SCCA National events and win the Northeast Division Championship in both Formula Ford and Formula B. Once done, this would qualify the cars for the National Championship Runoffs at Road Atlanta, which of course, he intended to win.

Success

To say that Stevenson met with success in the FB car in 1971 would be an understatement, but the season didn’t quite start as he had planned. At Lime Rock, Stevenson started last on the grid and despite losing fifth gear still managed to break the lap record and finish in 2nd place. He started on pole for the next six races at Thompson Raceway, Lime Rock, Pocono, Nelson Ledges, Watkins Glen and Bryar Motorsports Park. He was also first across the line in each of those six events.

Unfortunately, he wasn’t able to continue the success in the National Championship at Road Atlanta. Stevenson qualified 6th, but finished in 5th position. In a later interview Stevenson said that he should have won but the car suffered from “driver brain-fade.”

During 1971, Stevenson also drove the car at Road America, Mosport Park and in February/March ’72 in the El Premio Internacional Marlboro de Colombia Invitational Race in Bogota, Colombia.

Success followed in the ledger books with fresh orders for the Lotus 69, especially in Formula Ford guise. Unfortunately, when Lotus pulled the plug on constructing customer cars, Fred Stevenson was left with 17 unfilled orders for Lotus 69 FFs.

Sold On

Whether Stevenson was disgruntled with the whole scene or he simply decided that it was time for a new car is not known. Not long after returning from Columbia he sold his car to George Liebmann who raced it without any great success. Then, like so many competition cars, it passed through a number of hands, even being raced by some of them before fading into obscurity during the late 1970s.

Also like most old competition cars, it was never lost and was always known to someone. In 1987, Lotus 69 FB 71/69/6 was purchased by Australian John Wales, who imported it to Australia. At the same time he also re-imported an Elfin F5000, which would probably explain the curious choice of sending the Lotus to Elfin in the South Australian capital of Adelaide for restoration. On arrival in Australia the Lotus was painted black with a center red stripe. At Elfin, the car was completely dismantled, but sadly the company closed its doors in 1991 and the dismantled Lotus was sent back to Sydney.

Several owners and repairers later the 69 was just about as dismantled as a car could be. Work had been done on the chassis, Hewland gearbox, suspension pieces and so on, but the whole car remained in several cardboard boxes.

In 2004, Lotus 69 FB 71/69/6, in what could be now called a kit, found its way to Queensland and into the hands of a well-known collector. He soon decided, however, that an open-wheeler Lotus really didn’t fit into his plans and it was once again put up for sale. Enter Adam Harris into the picture.

Various Boxes

Adam bought the car and various boxes and other containers that filled every corner of his car trailer. Back at home, with the parts spread out over his garage, he was pleased with what he bought and was equally pleased with the work that had been undertaken over the previous years as it made him comfortable with the project ahead of him.

Anyone who has bought a car in pieces will know the feeling of uncertainty that everything is there, but Adam was satisfied. The chassis, while unpainted, didn’t appear to have suffered any accident damage and was complete, so any necessary repairs had been undertaken correctly. The body was also complete, but of course needed some work. About the only component that didn’t come with the car was its engine, but an approach to noted Australian racing driver Lionel Ayres proved successful with the result of Lionel providing a suitable rebuilt engine.

Following the painting of the chassis Adam set it up on a frame with a view toward assembly. It was a true restoration with everything repaired or refurbished. The car came with a set of body moulds, but these were unnecessary as the original body was in such good condition, and just needing paint in its original yellow livery. In all it took Adam close on to 18 months to put the car together.

Raceway

Adam’s first outing in the car was at Queensland Raceway and being a freshly refurbished car, some gremlins were expected. Mechanically the car ran perfectly, but an electrical connection at the front vibrated loose and resulted in quite a bit of worrying smoke. Luckily a quick disconnection of the battery saved the car from any great degree of damage.

Once that problem was resolved, the car never missed a beat. Further outings were had at Queensland Raceway and both Adam and the car really enjoyed a run through the streets of Murwillumbah during the sadly now ended Speed on Tweed annual event.

While Adam Harris certainly did a wonderful job at returning the car back to its former glory, other developments in his life were taking precedence over racing cars. Marriage and family were on the horizon, resulting in the Lotus being used only for limited events. Eventually Adam’s father Richard bought the car and continued to run the Lotus in what is known locally as GEAR events. Standing for Golden Era Auto Racing Club, GEAR is dedicated to the enjoyment of old racing cars and stages mid-week race meetings where the object is not winning, but enjoying the car in a non-competitive atmosphere.

Both Adam and Richard used the Lotus 69 in numerous GEAR events and while they enjoyed the car, Richard thought that he wasn’t realizing its full potential. This resulted in the difficult decision to sell it.

Initially it was advertised locally, but apart from a few people who really were only interested in kicking the tires, it remained unsold. Richard then decided to advertise it in Vintage Racecar and it wasn’t long before he was contacted by a prospective buyer in Switzerland. Numerous international phone calls resulted in the prospective buyer flying to Australia to view the car. A week later the buyer had turned from prospective to confirmed, and the Lotus was crated up and transported to Switzerland.

On reflection, Richard and Adam think it was a lovely car and had circumstances been different they both believe they could have campaigned it with a lot of enjoyment. As far as they could tell it didn’t have too many vices and certainly didn’t turn around and bite them on the bum when least expected. Richard did say he didn’t drive it as hard as Adam did, but both said that it was super responsive and very predicable in its road holding.

There is no doubt that Adam regrets the Lotus having to be sold, but he is philosophical with such things as racecars. However, with his wife and two young boys to care for he has far more important matters to turn his mind to. Adam does recall that the time he spent rebuilding the Lotus was one of the most enjoyable and satisfying in his life.

On Board

Once again we were at the Lakeside Park Circuit close to Brisbane, which is the capital city of the Australian state of Queensland. The circuit itself has had its ups and downs since the first race meeting was held there in 1961. Originally built by almost all volunteer labor, Lakeside seemed to be a million miles from anywhere so it didn’t really matter if your racecar sang out a decibel or two. Now, suburbia is just on the other side of the Armco and heaven knows what the circuit’s future will bring, but for the immediate future the track is secure. To run any car at Lakeside is like running with the greats, since Clark, Stewart, Hill, Brabham and Amon all competed there in the past.

Immaculate! That’s the only word to come to mind as I walk up to greet Adam Harris’ Lotus 69. As I lower myself into the cockpit, I am surprised that I don’t have to be a contortionist. I have found that so many open-wheelers have scant foot room and next to no room for your left foot when you’re not pushing the clutch pedal. It occurs to me that with bag fuel tanks on the side and no over-leg/under-seat tanks there is probably more room.

I found that Adam’s Lotus 69 is as conventional as you could imagine. Left leg in and on to the seat, followed by the right and then slip down while letting the legs go forward. What could be simpler? The right-hand gearshift comes easily to hand and the harness does up comfortably so that it doesn’t leave you with a squeaky voice. I think the only thing I was disappointed with was that the steering wheel was covered in black leather as I was expecting a red-covered wheel. Didn’t Jim Clark’s Lotus cars always have a red wheel?

I have often heard that Lakeside takes no prisoners and I surely wasn’t intending on becoming one. At the end of the main straight there is a sweeping uphill, right-hand corner called the “Karussell” where all the weight is shifted to the left side of the car. If a bloke wasn’t careful the rear right tire could easily spin, but as the tires looked relatively new this bloke took it back to second and was careful with his right foot.

Next comes a slight left-handed bend that, while I knew it was there, I suspect would have been flat out in fourth if you’re trying hard and I suspect that the car wouldn’t even notice. The “Bus Stop” left-hander comes next and it feels a little judicious to slow down a smidge but stay in fourth. Now, sweeping corners are fun as they allow for some play with the throttle to see what happens. At Lakeside it’s called “Hungry Corner,” but I suspect that the name has something to do with the circuit’s reputation as far as prisoners are concerned. So for me it’s a less than an enthusiastic third before running downhill and grabbing fourth halfway down. Then it’s a gentle right sweeper onto the straight. At a shade under a mile and a half the Lakeside circuit isn’t long, but the straight is of a length, even with its slight left-hand kink, that allows plenty of time for fifth and a little space for reflection on the previous lap. Next comes the “Karussell” again.

After doing the mandatory “Yes I’m a good boy” laps behind the camera car, I’m allowed out on my own. Now it starts to be fun, and while I am nowhere near what the Lotus can do I was starting to enjoy the experience. Comfortable, quick, predicable and just outright fun would be the best way to describe the car.

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis/Body: Tubular steel chassis and fiberglass body

Wheelbase: 7 feet, 8.5 inches

Track: 4 feet, 8 inches front – 4 feet 10 inches rear

Weight: 830 pounds (weight of rolling chassis and gearbox minus fuel)

Suspension: Front: Independent with coilover shock absorbers and anti-roll bar Rear: Independent with coilover shock absorbers and anti-roll bar

Steering Gear: Lotus rack and pinion.

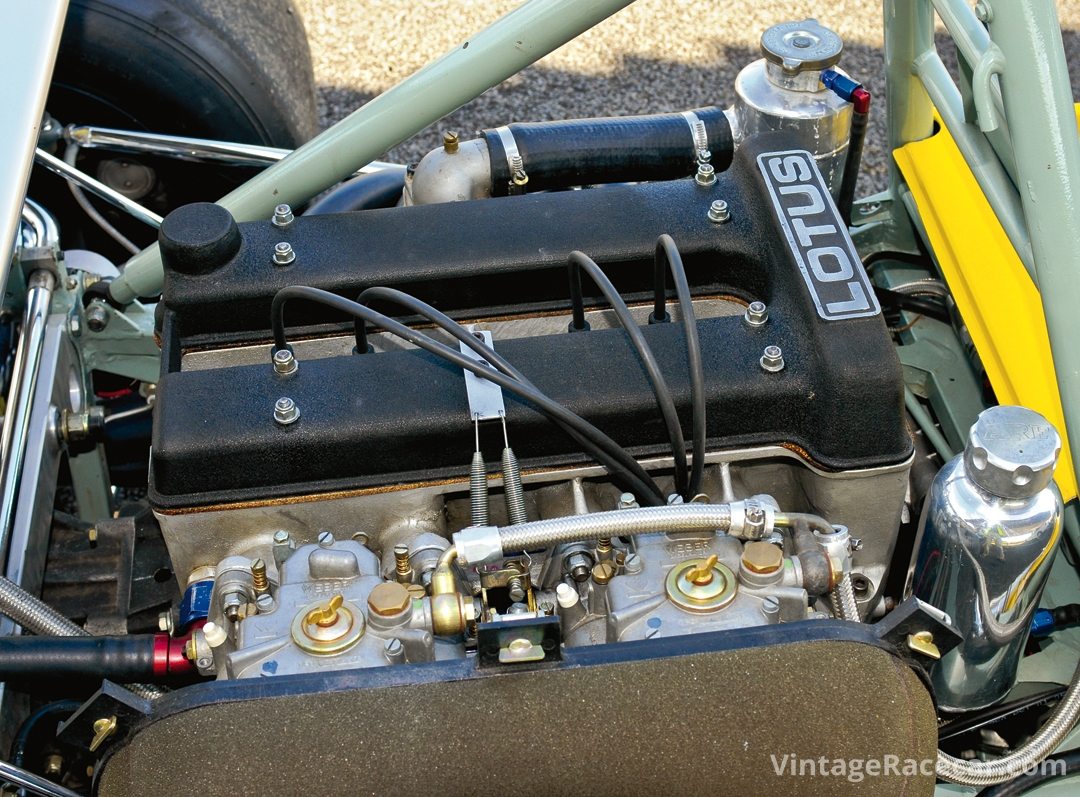

Engine: Lotus Ford twin-cam 1,595cc

Power: 180 hp at 7,500 rpm.

Carburettor: Twin Weber DCOE 45mm

Clutch: Single-plate.

Gearbox: Hewland FT200

Gears: 5 forward, 1 reverse.

Foot Brake: discs all around

Hand Brake: N/A

Wheels: Lotus 10-inch front & 12-inch rear

Tires: Front 245/515 x 13. Rear 290/595 x 13 Dunlop slicks.

Resources

Many thanks to Adam Harris for the opportunity of getting up close and comfortable with the Lotus 69.

Anthony Pritchard, Lotus – The Competition Cars. Haynes Publishing. ISBN 1 84425 006 7

John Tipler, Lotus Racing Cars, Dominance, Decline and Revival 1968-2000. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-2553-1

Marc Schagen, Lotus – The Historic Sports & Racing Cars of Australia. Freshwater Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9874201-0-7