I stood back watching, as Monterey feted the Fangio marque. Fangio marque? Yes, Juan Manuel Fangio is the only person, to date, to be so honored by the Monterey Historics. A weekend packed with his cars, his victories, and a reenactment, as far as it was possible, of his glorious career. And, biased though I was, I believe he deserved it. He was, after all, the only man to have won five Formula One World Championships until Michael Schumacher came along decades later. Such homage left this mechanic from the potato-growing town of Balcarce, 250 miles south of Buenos Aires, completely unruffled. He was like visiting royalty, but that’s not how he meant it to be. It was just his way. And people loved him for it.

It took me back to 1951, and my school days in Australia, when Juan Manuel Fangio won the first of his five Formula One World Championships behind the wheel of the mythical Alfa Romeo Tipo 159 and Stirling Moss was making his F1 debut at Bern, Switzerland, in the less-mythical HWM. I idolized them both and greedily devoured every newspaper and magazine article, every radio program, and every cinema newsreel I could find about them.

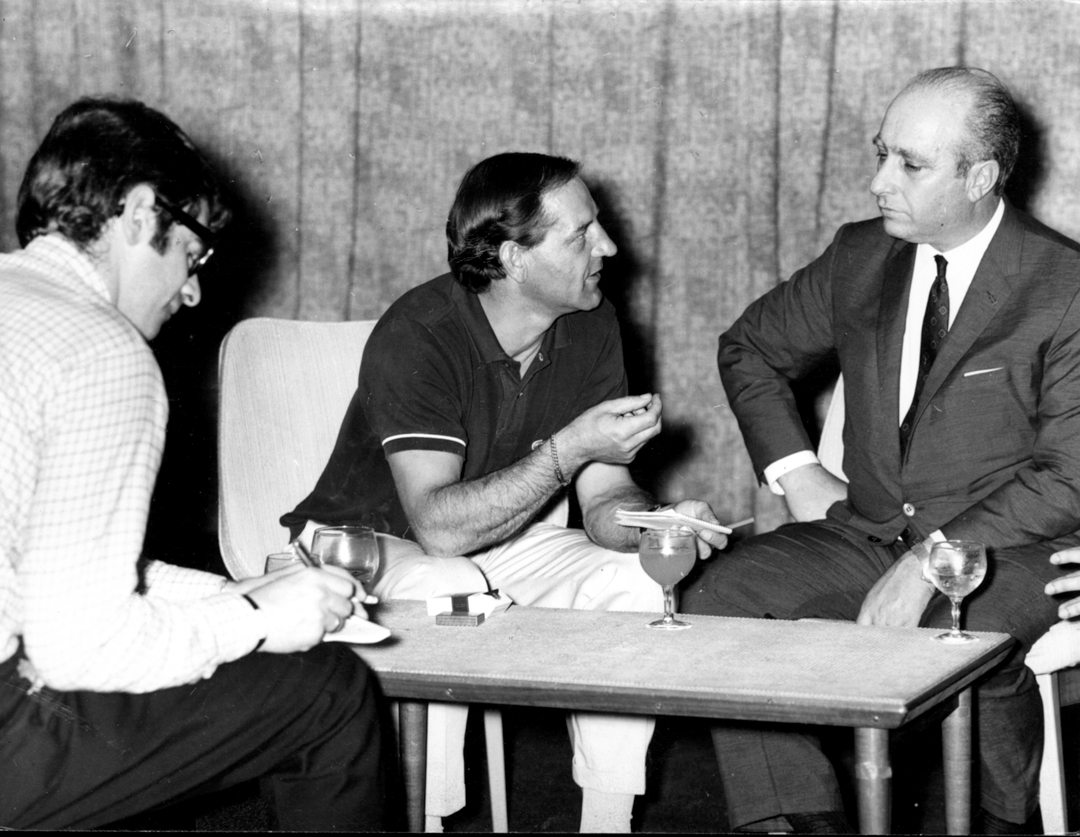

I first met Fangio 17 years later, when he was contracted to do promotional work for Pirelli. I was a lowly press officer in the tire manufacturer’s UK subsidiary at the time, and I arranged for Innes Ireland, the ex-Formula One driver who had just been appointed sports editor of Autocar magazine, to interview JMF. Innes drove us from central London to Heathrow airport in a Lotus Élan and there we waited in the VIP lounge with our interpreter, a second secretary in the Argentine embassy, until Fangio’s flight touched down. About 20 minutes later, the immaculately tailored, powerfully built king of Formula One was ushered into the lounge and, although he hardly knew Ireland, Fangio greeted the winner of the 1961 U.S. Grand Prix like a long lost friend and an equal.

When I got used to being in the same room as my hero—let alone actually shaking his hand—I began to notice that there was something special about him. He had a presence, a sort of magnetism I had not previously encountered, an almost royal bearing: He was quiet spoken, never interrupted; and those penetrating blue-gray eyes confirmed that he saw and understood everything. He answered Ireland’s questions with courtesy, humor, great attention to detail, and, where his opinion was sought, gave a clear and uncluttered statement of his views, nothing more and nothing less.

After the interview, Fangio and Ireland embraced once more before the Argentinean was whisked off to Claridge’s, the top people’s London hotel, in a sleek Mercedes-Benz.

I did not see Fangio again until 1986 at the press launch of my book With Flying Colours: The Pirelli Album of Motor Sport, a heavily illustrated history of motor racing from the first race in 1897 until the book’s publication 90 years later. The great champion had kindly consented to travel halfway around the world from his Buenos Aires home to be the guest of honor at the London launch. He had agreed to do so because he felt he owed my employers a debt of gratitude.

“I came here today,” the Argentinean champion said, “because I had an obligation to do so. When I came to Europe with my team in 1948, I had no money and nobody knew of Fangio. The company helped me. They gave me tires. That is why I am with you today.” A debt repaid 38 years later.

At the postpresentation lunch, Juan and I got to talking about future plans and he showed interest in me producing one of my illustrated books about him and his career. We had another book in the works at the time, so I suggested JMF’s should commemorate his 80th birthday, then five years away, and he seemed to like the idea. “It is possible,” he said with characteristic caution. In the end, we agreed I would send him my proposals for the book, and he would discuss them in Argentina with his business associates.

I did not tell Fangio who I had in mind to co-write his book at the time, as I had not had the chance to approach Stirling Moss yet. You can imagine how I felt some time later as I sat in Stirling’s gadget-filled London home (complete with a Kevlar lift, baked in Frank Williams’s autoclave) discussing a project, which, if it came off, meant I would be working closely with both my motor racing heroes for the next couple of years. Surreal!

After about an hour spent answering his searching questions, Moss agreed to put his name to Fangio: A Pirelli Album as coauthor with motor racing historian Doug Nye, and we shook hands on the deal. A handshake, by the way, is the only “contract” that has ever existed between Stirling and me in the 20 or so years we have known each other.

Back in my Milan office, I faxed Fangio confirming that the coauthor of his 80th-birthday commemorative book was to be Stirling Moss and concluded by saying, “We are going to give you the best birthday card you have ever had.” Within hours, he replied saying he was thrilled that his old teammate and opponent had agreed to co-write the book and immediately gave his approval of the entire project, including four exhausting trips to Europe.

A few weeks later, in April 1990, it seemed like disaster had struck. Stirling hobbled into Stuttgart’s Schlossgarten Hotel, the old Mercedes-Benz racing drivers’ haunt, on crutches with his right leg in plaster. He had been knocked off his motor scooter by a car in central London and had broken his leg. Moss had just spent a couple of weeks in the hospital encouraging the leg to mend sufficiently to allow him to travel to Germany with his lovely wife Susie in time for the book’s first photo shoot the next day on the Mercedes test track with Fangio, Karl Kling, their 1955 teammate, and two open-wheel W196.

But Stirling is a professional to his fingertips and, characteristically, he had already worked out how to take part in the photo session. He said with conviction, “No problem, old boy. My trousers will cover up most of the plaster. I’ll just turn my good leg on to the camera and lean against the car. It’ll be fine.” And it was; even away from the car Moss was able to balance precariously on his good leg for a couple of minutes at a time, looking for all the world as if his plaster cast did not exist and chatting casually with his old teammates.

After the photo session and lunch, Fangio and I began our 200-mile journey to the Nürburgring in a smart new Mercedes 500 SE press car, with me driving. To say I was nervous about chauffeuring the great champion is a massive understatement. But we eased our way through Stuttgart’s evening traffic and onto the autobahn without difficulty, my distinguished passenger with a vaguely uneasy expression on his face.

At the time, Fangio had to drink considerable amounts of liquid—mineral water, Coke, Sprite, 7-Up—due to illness. So about 20 miles out of Stuttgart, we pulled into an autobahn service area, had a soft drink, and bought a further supply of Sprite for the rest of the journey. Then it happened. Strolling over to the gleaming Mercedes, JMF said in his near-perfect Italian, “I have a good idea; you navigate and I’ll drive.” No criticism of my “conservative” driving style, just a hand out waiting for the car keys! For me, it was the chance of a lifetime: to be driven by the five-time Formula One World Champion.

I found it difficult to conceal my excitement as the Argentinean lowered himself into the big Merc, adjusted his seat, wheel and mirrors, started the car, and moved off. In minutes, we were doing a steady 125 mph in the outside lane of the de-restricted German autobahn, almost twice the speed of most other cars. Fangio just sat there, seemingly at peace with the world, the fingertips of his right hand at six o’clock on the steering wheel and the accelerator all but floored, whistling quietly under his breath.

At 78-years-old, that famous driving precision was still there. Especially when a German in a dilapidated Borgward Isabella suddenly lurched out in front of us at about half our speed and an accident seemed imminent. Fangio’s hands flew to the ten-to-two position on the wheel, he did some lively cadence braking and, in seconds, we were sitting there behind the old car doing 60 mph ourselves: no fuss, no drama, complete control. The Isabella eventually moved back to the center lane and Fangio immediately floored the accelerator of the Mercedes again; and that is where it stayed for the next 100 miles.

We turned off the autobahn at Koblenz and joined the narrow, twisting road that leads to the Nürburgring: It was there that JMF had an invigorating little dice with a BMW 735. The driver of the big Beamer was no expert and Fangio was in a hurry; he wanted a shower and some rest before dinner. But the BMW kept edging out into the oncoming traffic’s carriageway to stop us from overtaking. The ploy did not work for long, though. The Great Man saw his chance, calmly sliced the kinks off a couple of S-bends, and shot past the BMW without a word, just the faintest of smiles pulling at the corners of his mouth.

At the ’Ring’s hotel, news of Fangio’s arrival traveled fast: Everyone wanted to shake his hand. But the person he most enjoyed talking to was an elderly Spanish waiter who remembered that, in the ’50s, Juan always asked for room number 29 in the old hotel—now demolished—because it was the one with a bathroom en suite. After the stress of a day’s racing, JMF enjoyed a long, invigorating soak in his private bathtub.

Next day, shadowed by a couple of persistent autograph and memorabilia brokers who eventually made a killing from Fangio’s unstinting generosity, we drove over to the part of the old Nürburgring that had been assigned to us. There, Hartmut Ibing waited apprehensively. The German was the owner of the Maserati 250F in which Fangio won his fifth world title at the old circuit on August 4, 1957, a race the Great Man always acknowledged modestly as “perhaps the most important” of his distinguished career.

The red car sparkled in the morning sun as the tall, slim Ibing shook hands before we strolled over to where a mechanic was fussing with the car’s melodic engine. JMF walked casually around the Maserati and confirmed to Ibing when asked that, to the best of his knowledge, it was indeed the car he had raced that Sunday, 33 years earlier.

Fangio then walked back to our Mercedes, opened the boot, and pulled out a holdall, which had seen far better days: From it he produced the battered brown helmet and aero goggles he had worn the day he won his fifth title. Then, with the agility of a man 20 years his junior, he clambered into the car, blipped the engine three times, and accelerated away. Juan ran the 250F up and down our designated three-mile section of the Nürburgring a couple of times just to make sure it was in good working order, and then indicated he was ready to drive it for our camera car.

The growl of the six-cylinder engine was inevitably subdued as Maserati and driver begrudgingly kept the station line astern of our open-ended estate car, cameramen dangling from its tailgate. After two hours of shooting pictures for the book and sequences for a TV documentary to commemorate his 80th birthday, we had all the material we needed.

Ibing looked as if he would burst with pride, and his mechanic was smiling broadly at the sight of the great Fangio driving their car on the ’Ring again. As the Argentinean braked the Maserati and stopped next to Ibing, the German asked Juan what he thought of the car, which had been beautifully restored at great expense. Never a man to mince words, Fangio simply said, “Needs a new clutch,” with that poker face of his. But bruised pride or not, Ibing was delighted to have had the car authenticated by no less an authority than the man who won a Formula One World Championship with it.

Just before we left the track, we were given the necessary permission and Fangio told me to climb aboard the Mercedes 500 SE; he wanted to drive the old circuit again. What followed was a running commentary on how he set 10 consecutive lap records that day in 1957 in his successful attempt to overtake the distant Ferraris of Mike Hawthorn and Peter Collins, who thought they had the race in the bag.

JMF showed me humps from which the Maserati literally took off, corners in which he almost filled the car’s front air intake with mud and grass in hot pursuit of the two Englishmen. He called out the rpm and gear changes he had used at just about every bend and confirmed he went into every corner—not just one or two, but each one that called for a gear change—in a higher gear than usual. He grinned mischievously as he said he had never driven like that before and never did so again. “Troppo pericoloso!” (too dangerous), he remarked.

By the time we had finished a full lap of the 14.17-mile track, I felt immensely privileged to have been talked around the Nürburgring by its most accomplished conqueror. Fangio, though, couldn’t stop chuckling as the memories came flooding back: especially when he got to the one about, after dinner, when his chief mechanic, Guerino Bertocchi, took him to see the decidedly agricultural Maserati 250F and its air intake clogged up with earth and grass.

A week later, I met Fangio in Monte Carlo so that we could take pictures of him at the principality’s famous Grand Prix. It turned out to be a long, hard job because, as we photographed him that hot, sunny day in the organized chaos of the cramped pits, we could not move more than a pace or two without JMF being stopped by admirers, autograph hunters, and acquaintances. The situation was becoming difficult, because we had a lot of pictures to take and very little time to spare; and we were expected at the palace.

His Serene Highness Prince Rainier had invited us to his castle for drinks. So, while thousands of spectators sat comfortably in the stands wearing a mixture of shorts, T-shirts, bikinis, and baseball caps, Fangio and I were suffocating in shirts, ties, and smartly pressed suits as the Monegasque cab pulled up outside HSH’s regal home.

At the front gate, the white uniformed guards snapped to attention and, after I had explained who we were, their commander pressed a discreetly hidden button under his desk. In seconds, the prince’s press secretary was at my right elbow, ready to lead us across the palace courtyard to a gilded reception room. His Highness, silver-haired and impeccably dressed, was a gracious host and, after drinks and the obligatory photographs on the battlements, he offered to show us his stunning collection of vintage road cars.

Prince Rainier turned out to be a genuine enthusiast with in-depth knowledge of every single historic car that stood silent in his temperature-controlled, subterranean garage. Halfway through the tour, I “accidentally” let slip how disappointed we were that the Auto Club of Monaco could not find time in its prerace schedule for Fangio to drive a borrowed, open-top Ferrari 250 GT California Spider around the circuit on a couple of laps of honor, one with my photographer and one with me. With a wave of HSH’s right hand, the press secretary slipped discreetly away and our tour continued. Later, as we took the sun with the prince in the grounds of his castle home, the press chief returned and whispered in the prince’s ear.

“If you gentlemen would like to be at the club’s offices in half an hour, Mr. Fangio will be most welcome to drive two laps of the circuit,” Prince Rainier said in his excellent Italian.

That day, another of my many schoolboy dreams came true. After the photographer jumped out of the Ferrari, it was my turn to be driven around the elegant Monaco Grand Prix circuit on race day by the greatest Formula One champion that ever lived. The applause of the sensibly dressed race fans lining the track competed with the pleasant exhaust note of the 250 GT as JMF entered into the spirit of things and gave the crowd a modest sample of the driving precision for which he was famous. The casino, Mirabeau, station hairpin, tabac, Ste Devote—magic.

Ayrton Senna won that year’s Monaco Grand Prix in a McLaren Honda and, at the celebration dinner that night, he dedicated his victory to his motor racing hero, Juan Manuel Fangio. When Juan told me of Senna’s gracious gesture the next morning at breakfast, he was clearly moved.

After visiting friends in Europe, Fangio returned to Argentina. I was to join him there six weeks later with my designer and photographer, but before he left, JMF gave us carte blanche to photograph anything in or out of his amazing museum.

Balcarce’s single claim to fame is that it produced the man that Stirling Moss and lesser authorities regard as the greatest motor racing driver of all time—produced, literally. The town provided financial support for JMF and his brother Toto as they worked in the tiny garage still owned by the Fangio family to convert a series of innocuous vehicles—one was a taxi—into international race winners. On one occasion, the citizens of Balcarce even had a town collection to raise enough money for the Fangio brothers to buy a new car they converted into a South American road race winner. On another, they ran a public raffle that achieved the same objective!

Fangio never forgot the generosity of Balcarce. That is why he insisted on his museum, which houses all his trophies and many of his racing cars, being established in the town and not in Buenos Aires. That, too, is the kind of man Fangio was. Totally loyal to those he cared about and who cared for him. Needless to say, he gave us all the time we needed as we rummaged through his magnificent museum for our Fangio album. His generosity was unstinting, his commitment to the project total.

Publication day was June 24, 1991, and Fangio, the untiring traveler, was at both its international press launches, the first on his 80th birthday in the packed ballroom of the newly refurbished Dorchester Hotel in London and the second a day later at the Mercedes-Benz museum in Stuttgart. The Spanish-language edition of the book was given its send-off at a huge black-tie dinner party in Buenos Aires, attended by President Carlos Menem as his own tribute to the great Fangio.

A couple of years later, I toured South Africa, of all places, for 10 days with Juan Manuel, him the big star and me his Italian-English interpreter. On our day off, our hosts took us to a safari park outside Johannesburg. My last, precious memory of my friend Juan Manuel Fangio is of him sitting on a rickety chair in the lion cub enclosure of the park cuddling one of the baby lions and whispering endearments in Spanish into the little animal’s fluffy ear.

To say Fangio was special is like saying the Cullinan diamond is quite pretty. He had about him that natural air of a prince among men and was respected as such by us all. He only had to enter a crowded room and it would immediately fall silent. Respect and admiration for this remarkable yet simple human being filled the air. But he paid it no heed and was always the same. Quiet, never opinionated—yet he always had a firm opinion—always courteous, always modest and kind. Incredibly kind, with time for everyone. I feel deeply honored to have enjoyed his company and, later, his friendship for a small part of his life but a large chunk of mine. I still miss him, even though he died over 13 years ago at the age of 84.