This is the tale of a wonderful old racing machine, now fast approaching its 100th birthday but still enjoying an active competition life in the hands of vintage racing enthusiast and collector Andrew Larson.

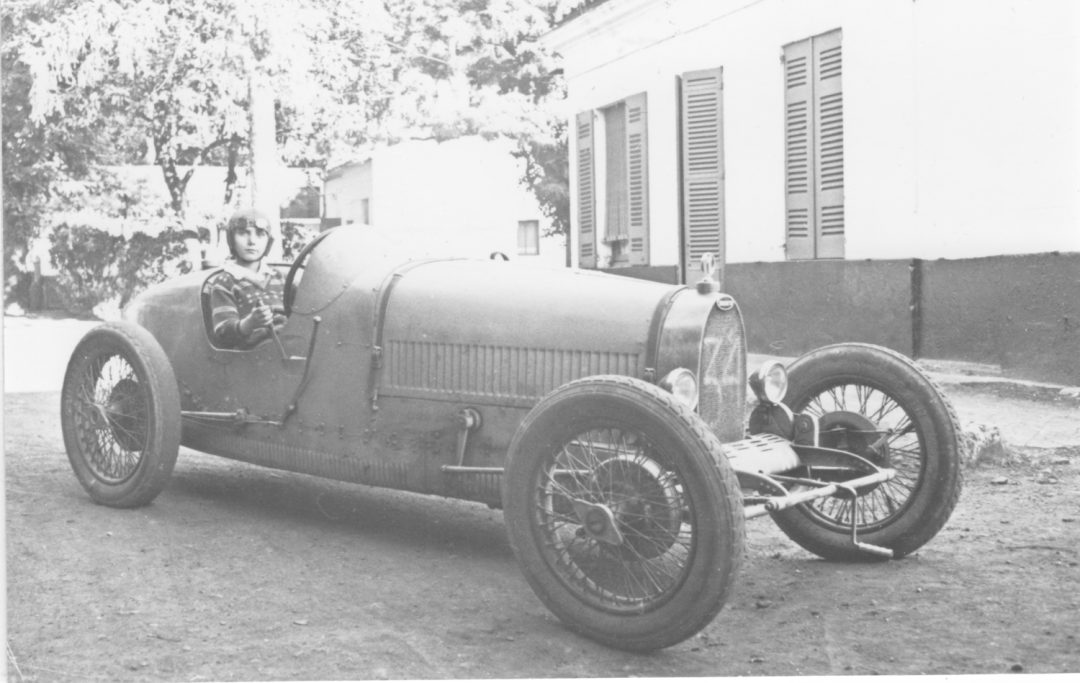

It’s a 1927 Bugatti Type 37A Grand Prix racer, chassis number 37265, and it has been driven by many individuals, including a Frenchwoman named Anne-Cécile Itier who delighted in pulling on her cloth helmet and goggles and mixing it up with her male counterparts. Before we relate her brief history with this car, we need to understand why the Bugatti Types 37 and 37A proved so dominant in their era and why they changed hands so often.

Today, it’s impossible to imagine any enthusiast, no matter how wealthy, being able to stroll up to the factory doors of, say Ferrari or Mercedes-Benz, placing an order for a new Grand Prix racing car, taking delivery, and then actually driving it in competition. That hasn’t always been the case. In the early days of motor racing, the sport was pretty much a rich person’s playground, and the only qualification was a suitable bank draft. Racing success helped sell new cars, so manufacturers rarely considered ability when an order was placed. They also were known to have played games when dealing with government bureaucracies.

Ettore Bugatti was probably the first automaker to sell Grand Prix-specification racers to the general public. Although best remembered as a brilliant mechanical engineer, artisanship was in Bugatti’s genes. His father created magnificent hardwood furniture, and other members of his family were gifted painters and sculptors. Ettore’s automobiles and those designed by his son Jean were not only wonderfully crafted, but pleasing to the eye. They were also very fast – and usually, but not always, quite expensive.

Bugatti’s earliest racing successes came with the tiny but advanced Type 13, which came to market in 1910. The Types 13, 22, and 23 later became known as “Brescias” for their sweep of the four top places at the 1921 Brescia Voiturette(Light car) Grand Prix in Italy. The light and quick Brescias remained in production until 1925, even as Bugatti’s larger-displacement Type 35 Grand Prix series, with their powerful 2.3-liter supercharged straight-eight engines, were cleaning up on the track. Although the Type 35s proved tremendously successful, they were very expensive, with exquisite machine finishing, built-up roller-bearing crankshafts and beautifully-forged, hollow front axles. At the end of the 1925 season, rules for the first World Championship were unveiled. Engine displacement would be limited to 1.5 liters, which made the Type 35 ineligible to compete at the highest level. For Bugatti, this proved a blessing in disguise; his response was the less complicated, normally-aspirated Type 37 with its smaller, inline SOHC four. The price of a new 37 was much less than that of a supercharged Type 37A, which in turn was half the price of a blown Type 35B – and 37s were far easier to maintain. They sold like hot crépes.

Bugatti experts suggest that the Type 37 could be considered an “Everyman’s Grand Prix car” because they were reasonably affordable. Many were purchased by amateurs, only to be re-sold within a year or two, sometimes after just a single race, because their owners quickly realized the limits of their driving ability. Others became stepping-stones for the more skilled drivers who moved up to faster rides such as the Type 35.

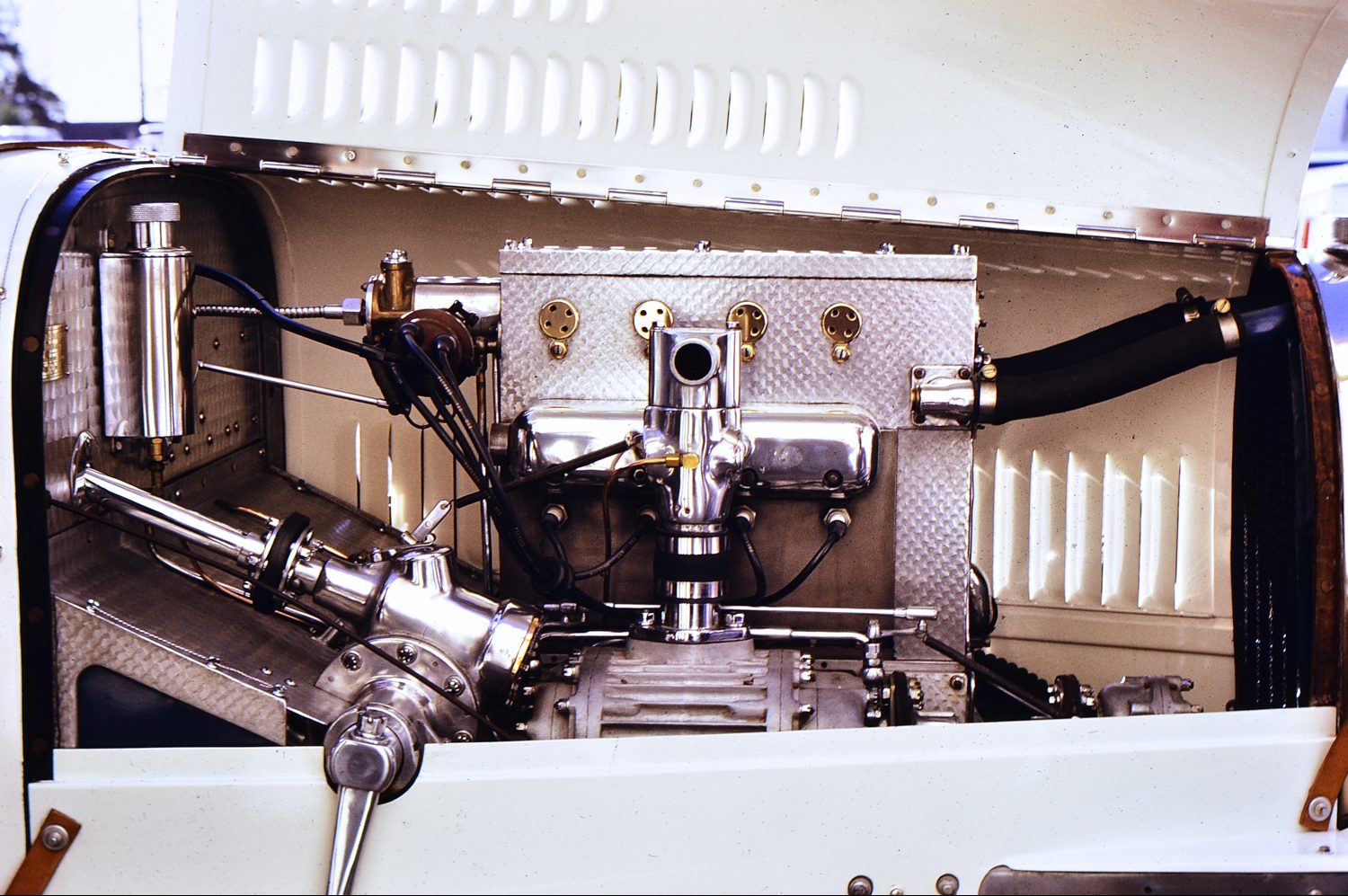

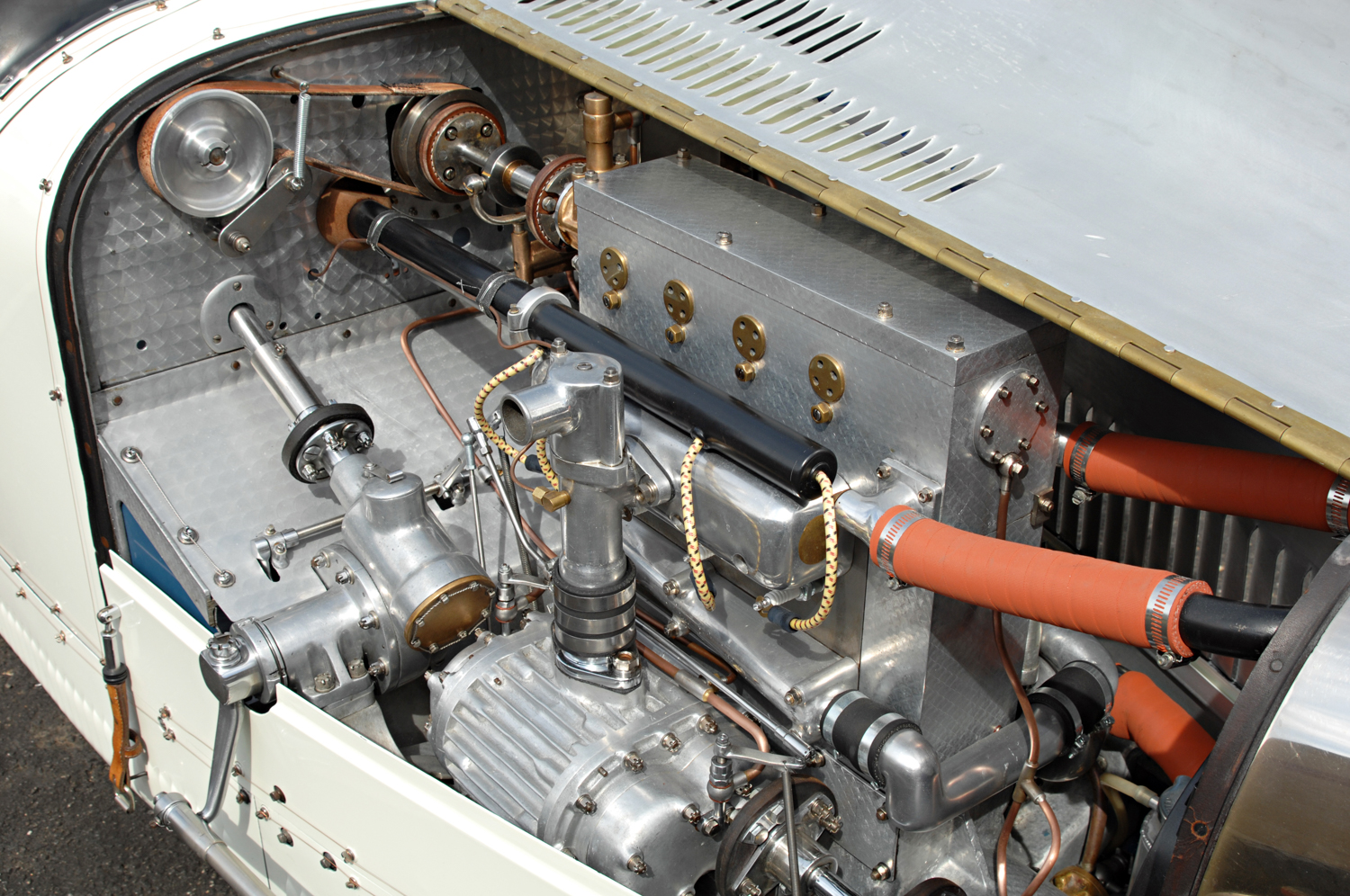

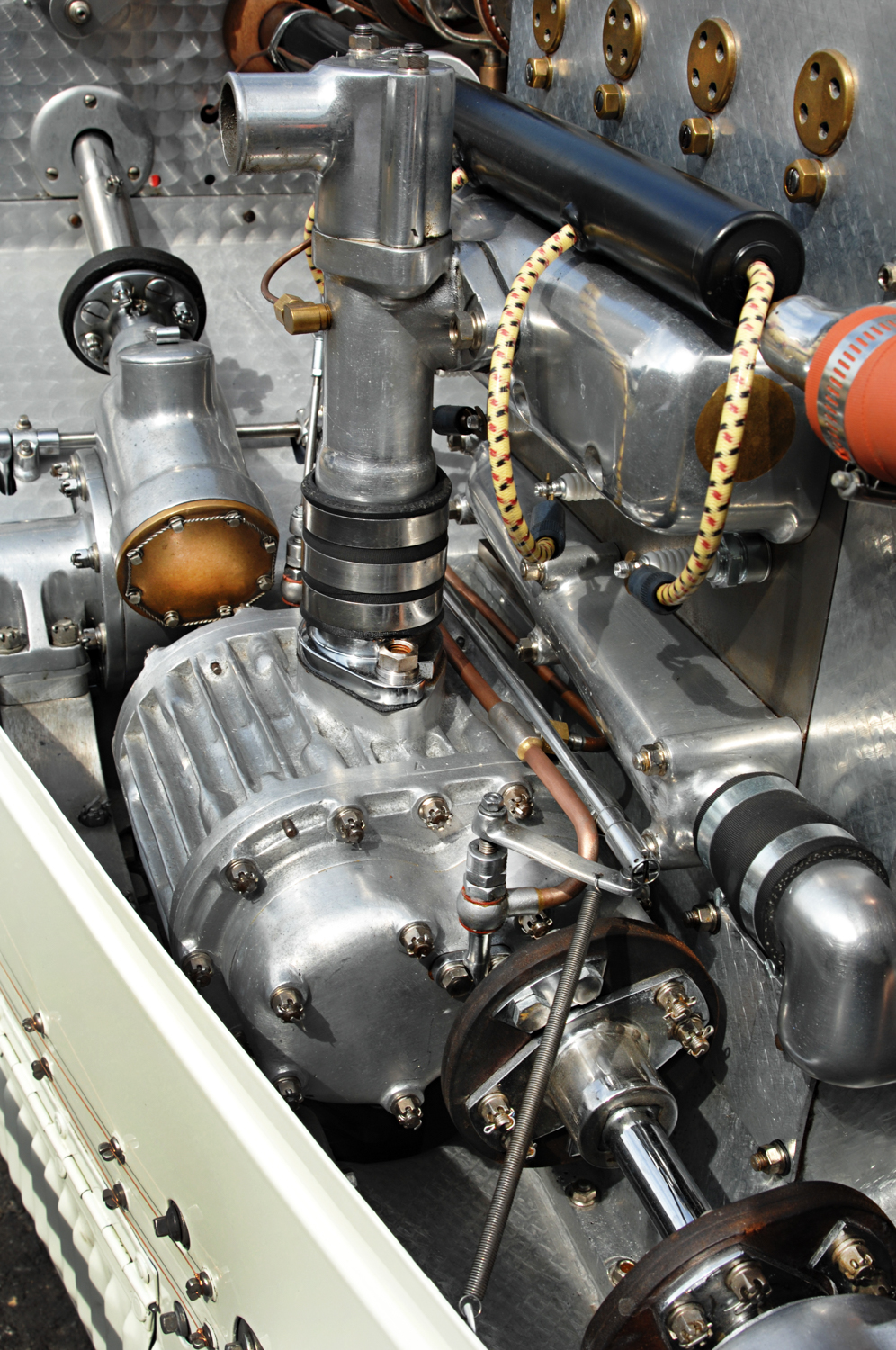

Most sources agree that between 1926 and 1930, about 290 Type 37s rolled out of Bugatti’s factory at Molsheim, in Alsace. Of that total, 79 or 80 were delivered with a small, low-boost (3-4 psi) Roots-type supercharger. These were eventually designated Type 37A. It’s believed that about half of these factory-built Type 37As survive today. A number of normally-aspirated 37s were upgraded to “A” specification over the years, including Larson’s. That wasn’t simply a matter of bolting on a blower and manifolding. The blower was driven by a set of angled gears in a two-piece housing attached to the nose of the crankshaft. From that housing emerged a short driveshaft with leather couplings at each end to maintain alignment. As a result, the steering rack had to be relocated, as well as other items added.

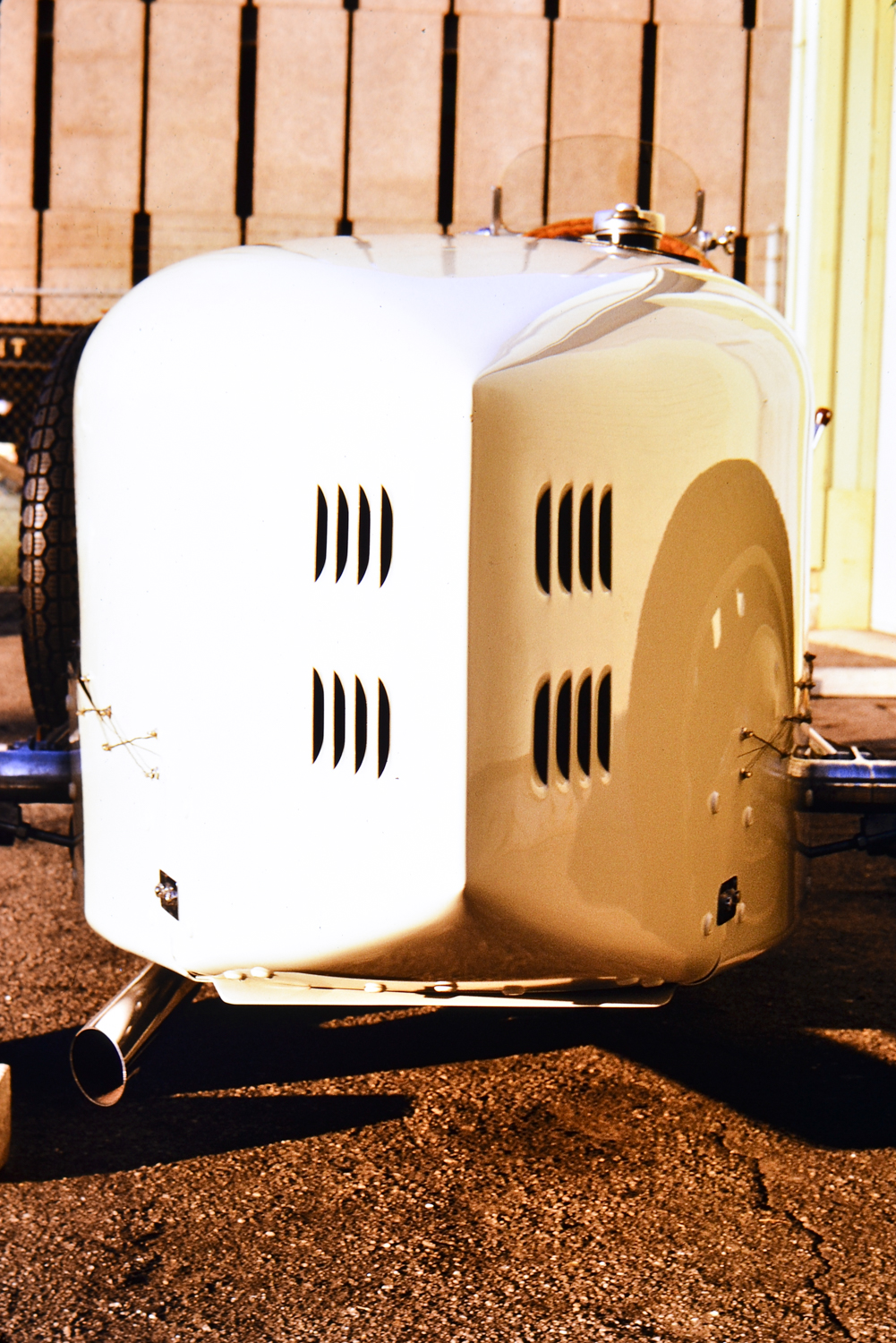

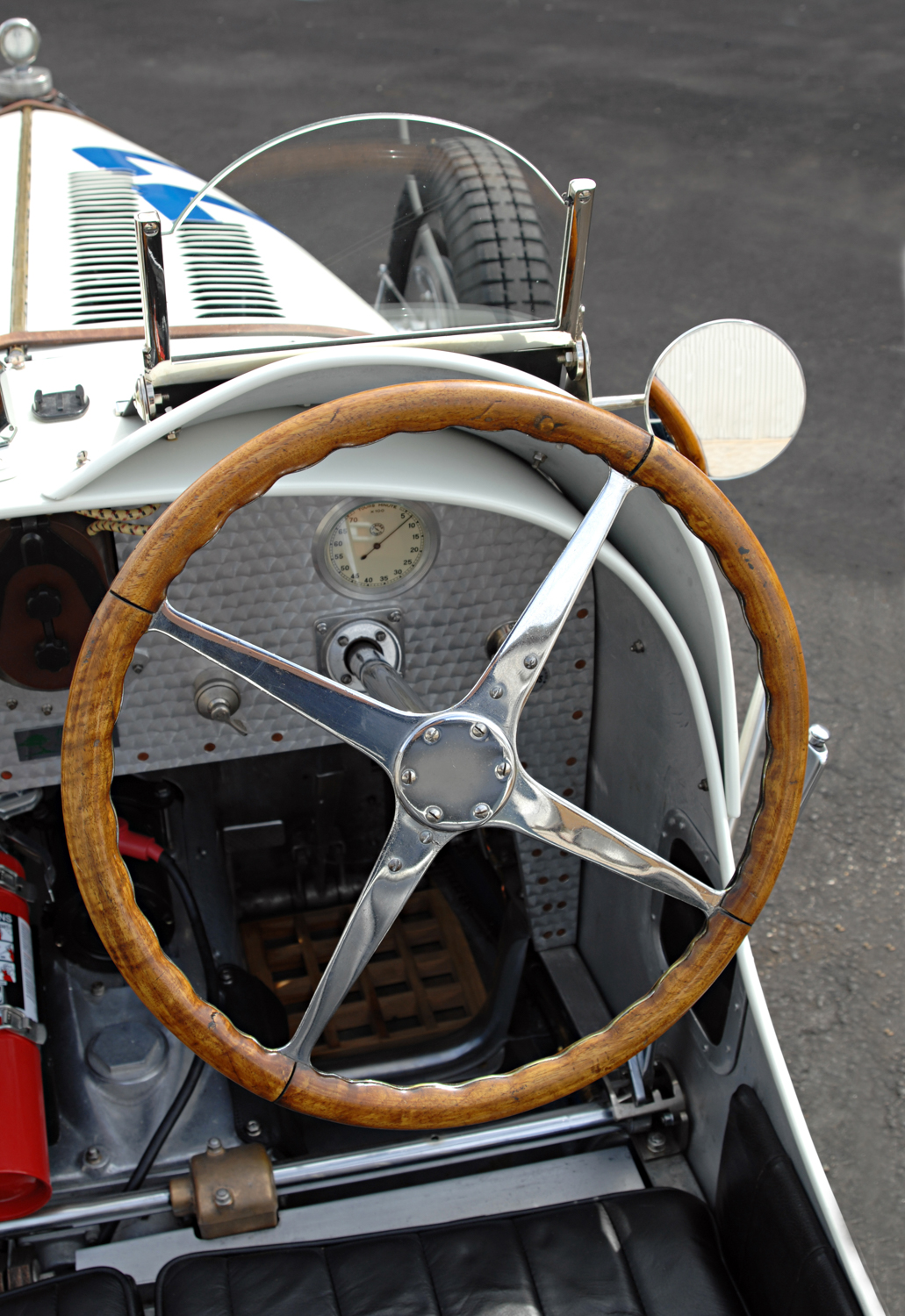

The Type 37 closely resembled the Type 35B, sharing a compact 94.5-inch wheelbase. The traditional ladder frame was clothed in light alloy panels secured by aircraft-type safety wiring. The tapered boat-tail housed a 100-liter gas tank; a single spare wheel was carried amidships in a bracket on the left side, where it helped to offset the driver’s weight. The bonnet side panels of the Type 37, held in place with leather straps, had a single row of louvers; the supercharged cars had two rows for better cooling. Bugatti’s traditional horse collar-shaped radiator shell rides above a louvered front valance.

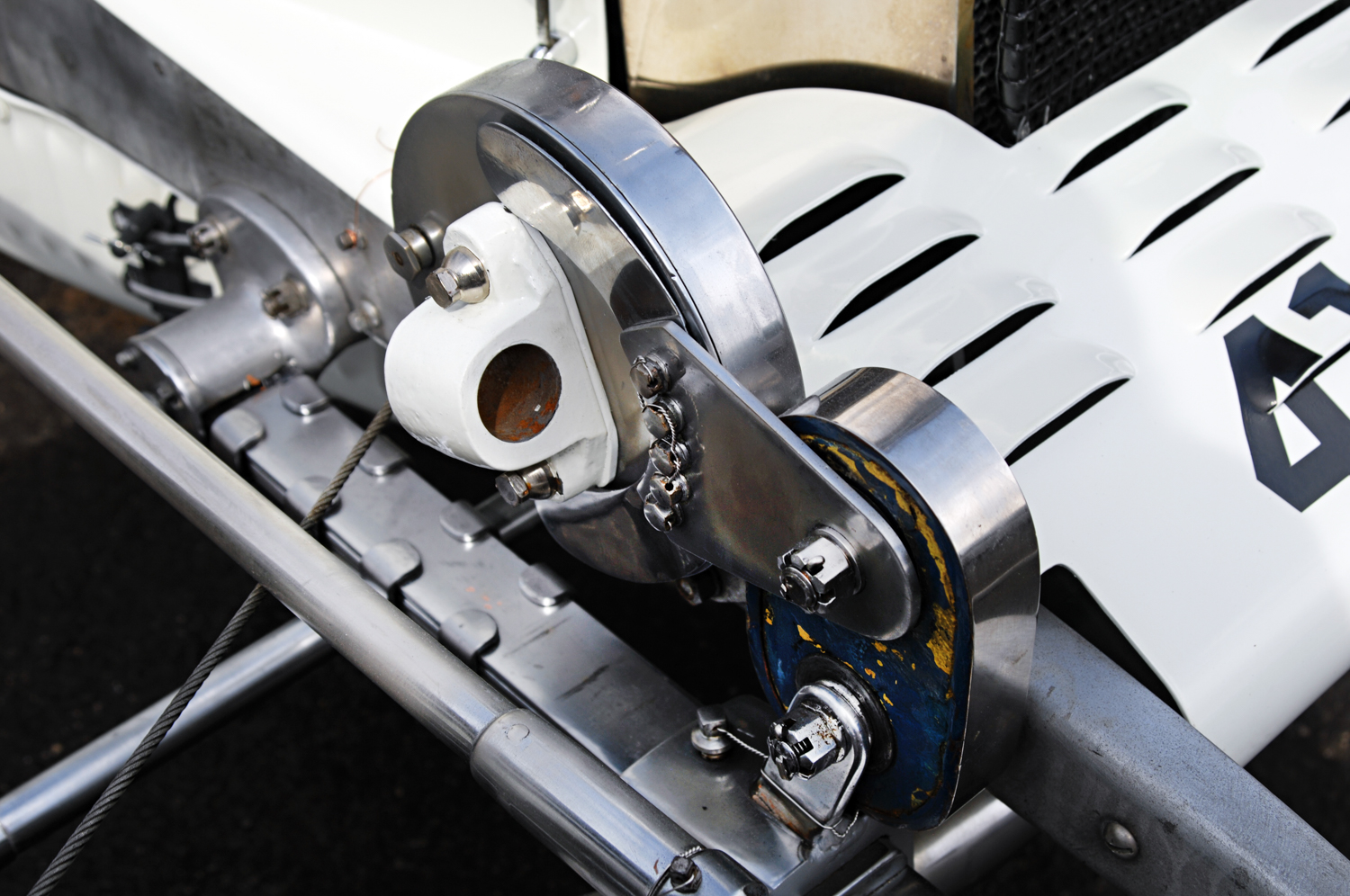

The four-cylinder engine itself comprises a cast-iron block and integral head. Being smaller and lighter than the straight-eight of the Type 35, the 37’s center of gravity moved a bit further back in the chassis and gave it improved balance and handling. The Type 37 had a smaller radiator and narrower bonnet, as well as smaller brake drums within their center-lock wire wheels. The introduction of the supercharged 37A included the addition of Bugatti’s familiar eight-spoked cast alloy wheels with integral brake drums borrowed from the Type 35, along with magneto ignition.

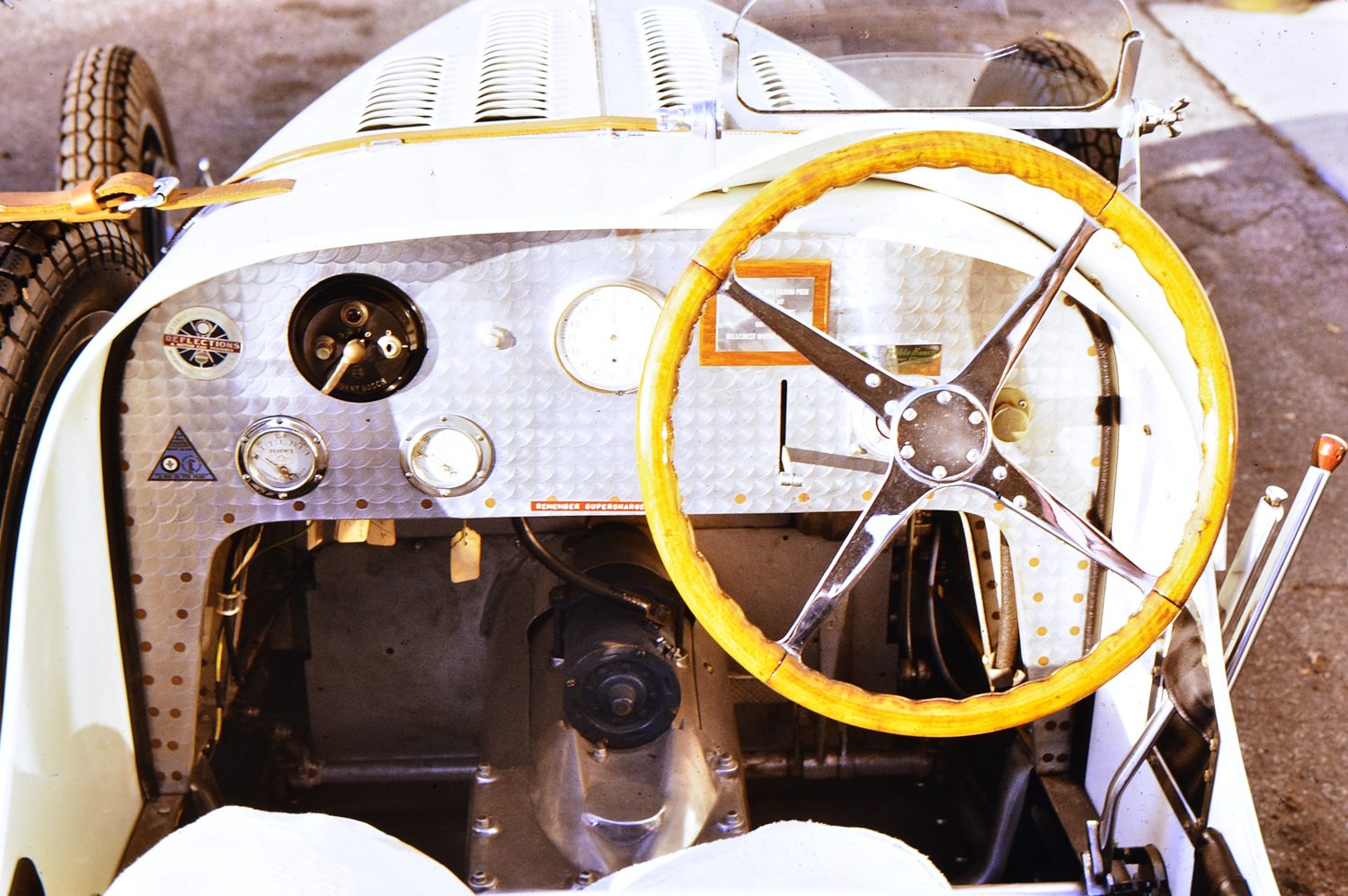

The light alloy crankcase follows standard Bugatti practice by incorporating longitudinal tubes within the cast sump along with deep fins to provide additional oil cooling. Bugatti engines were assembled completely without gaskets; such was the precision of the manufacturing and assembly process. There is a small auxiliary oil tank, pressurized via a hand pump, beneath the passenger seat. The single overhead cam is shaft-and-bevel gear driven from the front of the engine, controlling two intake and one exhaust valve per cylinder. The bore is 69-mm, the stroke 100-mm, yielding 1496-cc using a plain-bearing billet crankshaft. This modest displacement yields a reliable 60 bhp unblown, or well over 80 bhp in supercharged configuration. Fitted to the right side of the engine, the supercharger has its own small drip-feed oil reservoir mounted on the passenger-side firewall. The tachometer is belt-driven from the back of the cam box. The Type 37’s coil ignition was replaced by a magneto. With careful balancing, these little undersquare engines can be routinely spun to 5000 rpm without complaint.

The four-speed manual gearbox, with a reverse-“H” pattern, was originally fed through a multi-plate wet clutch, but just about all 37 and 37As running today utilize a stack of dry discs. The gears are stirred via a lever that emerges through the right side of the narrow cockpit. The front suspension comprises a simple beam axle— another cost-saving step —with a pair of semi-elliptic leaf springs. In the rear was a live axle with inverted quarter-elliptics. Hartford adjustable friction shock absorbers calm the ride. The four-wheel drum brakes were cable-controlled and when properly adjusted could easily stop this lightweight (just over 1500 pounds) racer from its top speed of about 100 miles per hour in un-boosted form (almost 120 with a blower). A lever-operated handbrake flanked the cockpit. Interestingly, viewing “Bugs” from straight on, they seem to be blessed (or cursed) with marked built-in positive camber. We should note that these Bugattis were successful not because of sheer speed, but because they offered superior handling and were very predictable.

While primarily intended as an open-wheel Grand Prix racer, these little Bugattis could readily be converted to run in sports car events by adding fenders, road-legal lighting, and a different windscreen. Supercharged Type 37As entered all the great road races of the day, including the Targa Florio and Mille Miglia, accruing excellent results, and proved competitive for nearly a decade, scoring over 1,000 race and hillclimb victories from the mid-1920s to the mid-1930s, when competitors such as the blown, twin-cam ERA arrived. Many of the greatest drivers of that era found that a Bugatti was more likely than not to put them in the winner’s circle. Type 37s in both forms were light, agile, relatively comfortable and easy to drive, and most importantly, well engineered and usually very reliable. With that background in mind, let’s take a closer look at the intriguing life of Chassis 37265.

Larson’s late father Karl was also a Bugatti enthusiast, owning an eight-cylinder Type 57 with a Type 59/50B body. Karl and his wife ran vintage rallies in it, and she vintage raced it on occasion. After running the car at Watkins Glen in 2006, Andrew decided he wanted a Bug of his own. He enlisted marque expert Jim Stranberg at High Mountain Classics in Berthoud, Colorado, to find a suitable candidate.

As he has done with all of the notable racing cars in his collection, Larson began to research the history of this Bugatti in exacting detail. To document the car’s early life in Europe, Larson retained noted French marque expert and author Pierre Yves Laugier. Factory records indicate that 37265 was completed on March 27, 1927 as an un-supercharged Type 37, fitted with engine number 155.

Now things start to get complicated, perhaps because the records concealed a bit of sleight-of-hand. Bugatti had decided to enter the grueling Sicilian endurance contest known as the Targa Florio, staged on April 24, 1927, on the 108-km Medio Circuito Madonie. He sent two cars plus a spare (though there were several privateer entries as well). The three were listed as 37264, 37265 and 37266, and all were listed as Type 37As. This is curious, as Bugatti did not introduce the blown T37 to the public until June of 1927, and they weren’t called “A”s until somewhat later. As we will learn, there is no evidence that 37265 was fitted with a supercharger until the late 1940s.

Another important number now enters the picture – literally. Racing cars of that period were customarily driven to events over public roads, and that required registration numbers from their country of origin – and those numbers were somewhat limited, especially in France. That may have prompted some extra-legal shenanigans. Documentation unearthed by Dutch Bugatti historian Michael Müller indicates that on April 2, 1927, the three new cars sent to the Targa Florio were duly registered in Strasbourg. This example, thought to be 37265, was assigned French registration 4127-J4. As that number appears on the tail of a Bugatti parked at the Targa Florio, we are left with the impression that Mr. Larson’s T37 did indeed reach Sicily, and with one of the other team cars crashing out in practice, likely ran the event. However, with thefactory build sheets showing 37265 being delivered as a normally-aspirated car, how did it become a Type 37A?

The most likely answer is that the Targa entries were entirely different cars, and the factory moved ID plates and registration numbers around. It makes sense that the factory would have wanted to run its most competitive, i.e. supercharged, cars at this important event. Thus, we can conclude that 37265’s identification plate and road registration number were switched to a pre-production T37A. Bottom line: 37265’s identification plate and registration number ran the grueling Targa Florio, albeit on a different car.

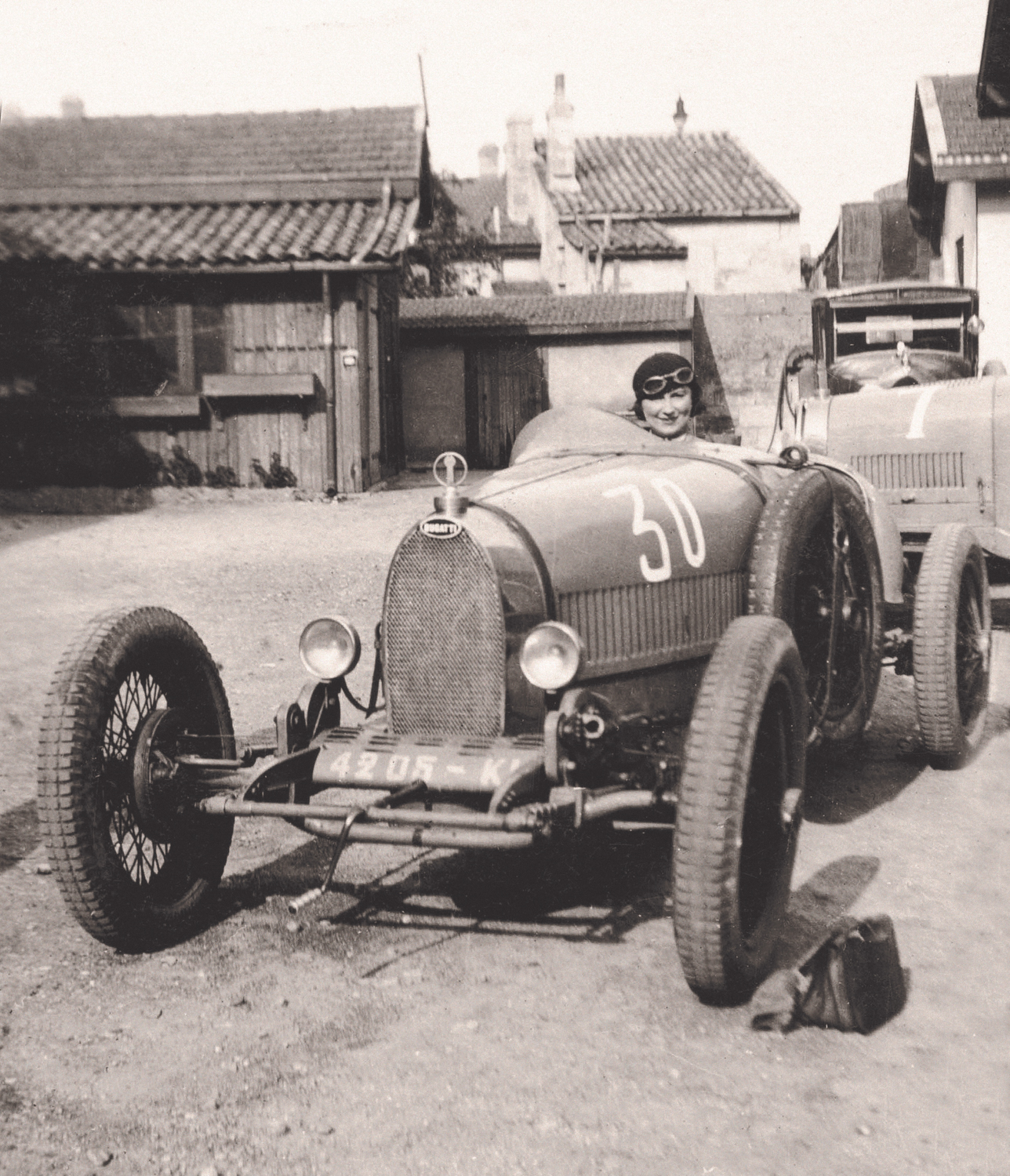

After the race, the car returned to Molsheim. The ID plate would have been installed on the “real” non-supercharged 37265 and sold through the Bugatti agency in Paris, where it was delivered to its first owner 11 days later. The original buyer’s name is unknown because Parisian records prior to 1950 no longer exist. In October 1927, the car was sold to Biarritz-area gynecologist Dr. J. L. Lafourcade, and on April 18, 1929, the car was acquired by Mr. Leon Parisot, another amateur from Bordeaux who would play an interesting role in this car’s history. Parisot entered his Bugatti at the Le Concours de Cote de Bordeaux-Monrepos time trials on June 29, and invited his good friend Anne-Cécile Itier to join him. Anne-Cécile was already an accomplished racing driver. At the age of 29, she had gained considerable circuit-racing and hillclimb experience with an Amilcar and other marques. One Bugatti historian says “Anne Itier was probably the best woman driver from 1927 to 1935”, which covers a lot of territory, including Hélène – later Hellé – Nice, nicknamed “The Bugatti Queen”…and the brilliant Czech Elisabeth Junek.

Parisot was sure Anne-Cécile would do well, and she didn’t disappoint, finishing second over the 1.3-km course. After changing the entry number on the car, Parisot made his own runs and finished in third place. Parisot also drove 37265 in the 12-lap IV Grand Prix du Comminges August 18, 1929, but is shown to be a DNF. Bugatti club records show him winning the Monbazillac hillclimb with this car in October.

Parisot kept the car almost exactly one year, selling it to Francis Peyrissac, on April 17, 1930. Dr. Laugier next traced the ownership to Marcel Bertrand-Bord of Périgueux on March 14, 1931, who quickly re-sold it a month later to Henri de Sainte Mathurin in St. Savinien, whose family reputedly became immensely wealthy buying and selling opium from Indochina. Mathurin kept the Bug just eight months before selling it on November 14, 1933, to Maurice Pinel, who lived near Marseille. Pinel held onto 37265 until February 26, 1936. Jean-Baptiste Oliovero owned the car for a period of 15 months, after which it was sold to Pierre and Jacques Regis. They quickly re-sold it to a Mr. Rocatti, with whom it lived for one year. From June 27, 1938, and through the war years until March 19, 1946, the car was registered in Paris to an unknown enthusiast. Prior to the war, one of these gentlemen had fitted 37265 with a Zagato-flavored roadster body with full fenders and road equipment.

A Parisian named Monestier bought the car five months later, then sold it on August 9, 1946, to 24-year-old Jacques Pollet, who later raced Gordini Formula 1 cars. In 1948, Mr. Pollet decided to upgrade his Type 37 to “A” spec. He bought the lower crankcase from engine #228 which had been originally installed in a T37A (ex-Baron Phillipe de Rothschild). Pollet also installed a T37A supercharger and alloy wheels. Pollet enjoyed the car until October 8, 1951, when he passed it to an enthusiast in northern France. That individual kept the Bug until March 16, 1955, when it was sold to Francois Mortarini and Armand Beressi, partners in a Paris-area Bugatti garage called Le Haras des Pur Sang de l’Automobiles. In 1955, the car was purchased by amateur racer Otto Zipper in Los Angeles. Zipper had immigrated to the United States after the war and was working as a mechanic for the wealthy collector Tommy Lee. He also began to import interesting European cars. He also owned and raced Bugattis, including this one. Zipper and his future business partner Bob Estes eventually opened what would become a famous and successful Porsche franchise in Beverly Hills.

In 1960, Zipper sold this T37A to Joe Ricketts, a partner in Storey-Ricketts Volkswagen in Long Beach, California. Mr. Ricketts eventually entrusted 37265 to nearby Bugatti expert “Bunny” Phillips who re-created the car’s original boat-tailed body, painting it white to reflect American racing colors. In 1966, Ricketts entered the car at the Pebble Beach Concours, where it took home a class award.

Around 1967, Ricketts sold the Bugatti to Willet Brown, owner of Hillcrest Motors in Beverly Hills. After Brown’s passing in 1995, his estate offered his collection through auction house Sotheby’s. The successful bidder for the Bugatti was Michael Gertner, who had 37265 restored by Phil Reilly’s shop in Corte Madera, California and immediately took it vintage racing at the Monterey Historics. Gertner sold the car to Jan Voboril, in 2005 and three years later Voboril sold the car to Andrew Larson.

A few years ago, Larson told Hagerty’s that he’s tried to keep his car as historically correct as possible. He decided to retain the white paint, as it had been that color longer than it was French Racing Blue. Besides, he says, “White stands out in a crowd of blue Bugattis.” When Andrew bought the little Bug, it had been fitted with a Carter carburetor, which was retained for street use on pump gas. He uses a Winfield carb for racing, the better to swallow the methanol-blend fuel the engine prefers. A period-correct magneto had been installed, but Larson has converted it to a modern electronic ignition hidden within the magneto case.

Larson, who is fairly tall, lengthened the steering column and removed some of the seat padding to allow his legs more room. The alloy T35 spoke wheels are replicas; he didn’t trust the originals for racing given their age. The car is quite fast, says Larson; he’s pleased that he can easily run with, and often beat, eight-cylinder competitors. “I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that Pollet or de Rothschild tweaked the engine a bit back in its French days,” he says. He’s also since learned that both the bonnet and belly-pan now on 37265 also came from two de Rothschild cars. Andrew continues to improve the car; he managed to purchase a rough but very original Type 37 rear body and floor section as well as a dashboard at Retromobile 2020.

Larson’s diminutive Bug is a frequent vintage race entrant on both coasts and always performs well. At Monterey’s Bugatti Grand Prix in 2010, there was an excellent entry of 34 cars (30 would start). “I finished ninth overall and was the fastest four-cylinder car, so I was proud of that!” At Lime Rock’s 2018 Bugatti GP he was third overall and again first in class.

In a few more years, 37265 will become a centenarian. Beneath his bowler hat, Ettore, who left us in 1947 at age 65, would smile and light a cigar.

Photography by Dennis Gray, Bill Wagenblatt, Dan Vaughn, and by permission of the Pierre Yves Laugier Collection, with additional photography by Timothy Barton and William Taylor.