Ferrari 512S

In 1967, the 512 was born out of a series of bad decisions by racing’s ruling body, the CSI, that were aimed at slowing down the 7-liter monsters like the Ford Mk IVs, which were dominating sports car racing. So the prototype class had a 3-liter limit imposed on it while the sports cars could do almost anything they liked up to 5-liters, provided 50 cars had been built. This figure was later reduced to 25 examples. In 1968, the CSI thought they had managed to control the growth of racing engines, but in early 1969, Porsche unveiled the 917 and immediately it was evident that the 3-liter prototypes were in trouble. Some four weeks later, Ferrari announced that it too had 25 new cars, designated the 512S – 5 for 5 liters, 12 for the number of cylinders and S for Sport. As the story goes, when the man from the CSI came to see the 25 cars, Enzo Ferrari pulled a fast one on him. Whereas at Porsche, all 25 cars were neatly parked in a row, at Maranello, the CSI rep was taken to see the first 13 cars and was then escorted to lunch before they would trek over to Modena to see the other 12. Of course, during the long lunch, 12 of the first 13 were trucked over to Modena for the afternoon inspection!

It was against the backdrop of Fiat support, and with a 6-liter engine already in use in Can-Am, that the 512 rapidly developed into an attempt to challenge Porsche supremacy. The 512 was based largely on the design layout of the successful P4, and the 4993 cc engine was derived from the 612’s 6.2-liter power plant, with a new crankshaft and a reduction in the bore and stroke to 87 x 70 mm. Many standard Ferrari sports car traditions found their way into the 512, including the single-piece crankcase sump, the Borg and Beck clutch and 5-speed Ferrari gearbox with ZF limited slip differential.

Again, like the successful P4, the chassis was a semi-monocoque, with a collection of triangulated tubes in the rear section and multiple fixing points for the engine – adding to an already rigid package. The 512 chassis was considerably more rigid than the Porsche 917’s aluminium welded space frame, which “flexed” according to many drivers. While a driver’s first experience of the Porsche’s flex was pretty frightening, this “softer” approach to chassis design meant the Porsche tended to adapt better to differing circuit conditions and to changing weather. Due to this pliability, the Porsche was a much better car in the wet.

The first 512S’s were fairly elegant in shape, devoid of spoilers and wings, using just a nicely upswept tail for aerodynamics. It didn’t work, however, and it wasn’t long before the 512S started to sprout aerodynamic wings, flaps and assorted ugly contrivances. It isn’t entirely clear when all 25 cars were completed, and the 512 still presents some problems for chassis number buffs. The numbering system used the 25 even numbers from 1002 to 1050. Of these 25, a few cars were built as spyders, including our test car, chassis 1006, which was the third car built, but the majority were berlinettas. The confusion comes from two sources: some spyders became berlinettas, again including “ours,” and all 512M’s started out as 512S’s, though not all 512S’s became 512M’s! I hope you are following me here. This latter confusion isn’t actually all that difficult. In late1970 and through 1971, a number of cars were modified and upgraded with factory improvements and were subsequently known as 512Ms.

The following chassis remain in 512S spec: 1004, 1006, 1012, 1016, 1022, 1032, 1038, 1042 and 1046. Chassis numbers 1002, 1008, 1014, 1018, 1020, 1024, 1028, 1030, 1036, 1040, 1044, 1048 and 1050 became 512M’s, and some of both were eventually destroyed, a few have been rebuilt as replicas, while 1010 later became the 7-liter 712 Can-Am car.

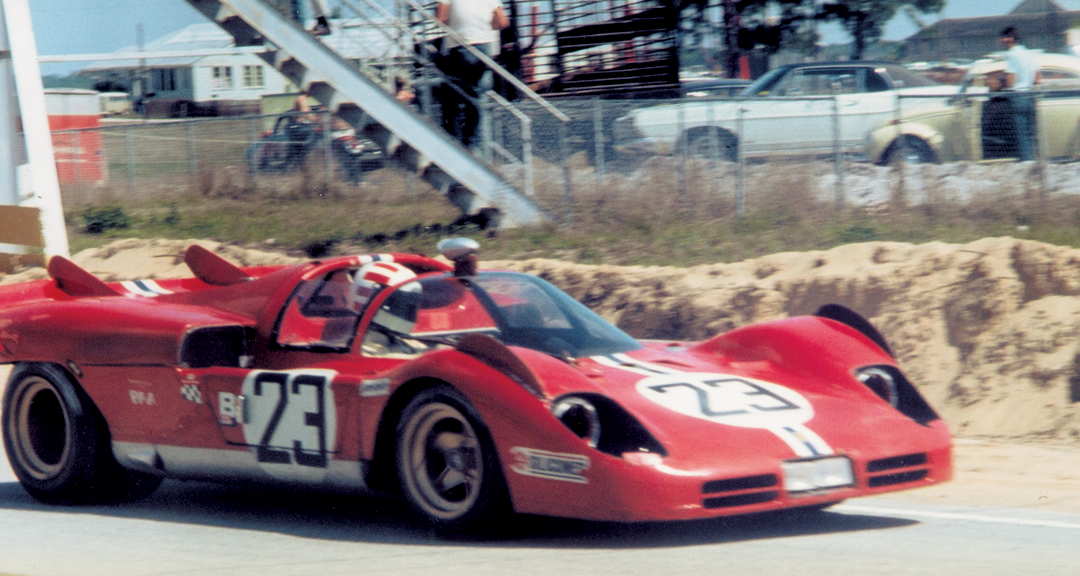

Chassis 1006

In many ways it is difficult to say that our test car had an illustrious career, if you measure that in terms of victories, or even good results. It didn’t win any of the seven international events it took part in, and its best result was second at the Daytona 24-Hours in 1971, the other results being a 7th, an 8th, a 9th and three DNFs. But 1006’s cockpit was the home for some pretty interesting characters: Americans Ronnie Bucknum and Sam Posey gave it its debut at the Sebring 12-Hours in 1970, where Mario Andretti, Ignazio Giunti and Nino Vaccarella took the late race victory from Steve McQueen in the first big win for the 512S. Andretti had been sharing with Arturo Merzario in 1010, which broke, and he moved over to the winning 1048. Ickx and Peter Schetty also retired in 1042 as did Bucknum/Posey in “our” car, which was entered by NART (North American Racing Team).

Photo: Pete Luongo

Later in the year, again as a NART entry, Mexican Pedro Rodriguez had two frustrating events in the car, the Can-Am races at Mid-Ohio and Donnybrook, where a 512S was just not strong competition for McLarens and Lolas (though in light of that, 7th and 9th were perhaps not too bad). 1006 then didn’t race until early 1971, when NART sent it to Buenos Aires for the 1000 Kilometer race with Sam Posey again, and locals di Palma and Nestor Garcia Veiga. Siffert and Bell led Rodriguez and Oliver in the two Porsche 917s, which had won all but one of the 1970 championship races; and Giunti was killed when his new 3-liter 312P crashed into Beltoise’s Matra, which the Frenchman was pushing back to the pits at the time. 1006 finished 8th behind two 512S’s and a 512M.

Then came the Daytona 24-Hours, by far this car’s greatest race, not only because it managed to finish second, but also because it was about the only time a 512S seriously tested the Porsche 917.

The Ferrari’s 550 bhp at 8500 rpm was more power than the Porsche could muster. But the Porsche had just seemed better at getting its power to the ground and had the edge when the weather was wet or even a bit damp. The Porsche record was vastly more impressive by this stage, but still the Ferraris had provided some hard racing, and in terms of sheer numbers, had always been a threat. In many ways, looking back, the results are less important than the fact that the two great manufacturers, Ferrari and Porsche, were going at each other hammer and tongs with these 200 mph beasts at every long distance race. The spectacle was often overwhelming. Porsche reliability, however, kept the tally going in favor of the Germans.

Photo: Ed McDonough

But at Daytona, the Ferraris gave the Porsches a real fright. First, Mark Donohue had the Roger Penske-run Sunoco 512M going very quickly and was able to lead the Porsches until several relatively minor problems set them so far back they couldn’t catch up. Ronnie Bucknum and Tony Adamowicz were in 1006, and for most of the race had been content to remain in the top six. Adamowicz, who was the subject of an interview in the December 2000 issue of Vintage Racecar, remembered the Daytona race in great detail when I talked to him about some of his most significant races.

“The thing I remember most about Daytona was having the chance late at night and in the early morning hours to be running close to Pedro (Rodriguez) in the 917. At most tracks you don’t have the chance to run so close and to have the same kind of visual effect where you see the other car for so much of the lap. At Le Mans, you brake and slow down to quite slow speeds and then speed up again, and you tend to lose contact and you don’t stay in close proximity to your opponent. But at Daytona, you do remain close. So, I had this period of time, which was probably a couple of hours, when I was running very close to Pedro, and we could size each other up. The Porsche had a very different chassis to the 512S. Our car was very stiff, which meant in the dry it was fast on the long stretches and on the banking. In fact, I could go up on the high side of the banking and get around Pedro, though I don’t think he was on the limit. The 917 was quicker in the in-field, but our car was really good on the banking. I even surprised myself by passing Mark (Donohue) when there was some rain and I could go high on the drier line on the banking and get past him.”

“Towards the end of the race we had moved up into second, but we were still a long way behind Pedro and Oliver. Then the Porsche had gearbox trouble and went into the pits, and after almost an hour we went into the lead, but by then we had some broken valve springs. Bucknum had been using a thousand more revs than I was and the valve springs went. Every time I went past the pits, I looked over to see if the Porsche was still there, but Pedro finally came out and caught us because we had slowed down to save the engine. It really was a good race for the 512S, which was so nice to drive at Daytona where you could use the power.”

Photo: Peter Collins

Adamowicz turned out to be one of the few people who had the chance to race both the 512 and the Porsche 917, having driven David Piper’s privately owned 917. Rodriguez was one of the others, along with Derek Bell (but Bell never raced Volvos which Rodriguez and Adamowicz did!).

Bucknum, partnered by Sam Posey, was out again in 1006 at Sebring in 1971, which is when I saw it race, though it didn’t finish due to a blown tire and made all the worse by Bucknum trying to drive a full lap with the sump scraping the ground. The Martini Porsche of Elford/Larousse won after the famed Pedro/Donohue incident in which Donohue said Pedro had pushed him and the Mexican argued that, “Donohue sort of backed into me at the hairpin!”

1006 only did one more important race, Le Mans in 1971, where Masten Gregory and Canadian George Eaton retired in the fourth hour with fuel feed problems. Of the nine 512 models at Le Mans, only 1006 remained in 512S trim, while Adamowicz was now in a 512M (1020) and finished 3rd.

With the new FIA rules coming into effect in 1972, the 3-liter class returned and the fabulous 5-liter cars were dead, relegated to the Interseries and the occasional national race, but in truth they had been legislated out of existence. While the 3-liter cars provided some good racing – the Matras, Ferrari 312s, Alfa Romeos and Mirages made for interesting racing for a few years – the 5-liter spectacle was gone. Even though I managed to take part in some of those 3-liter races, I wished I had been a few years earlier, but I was sure glad I had seen them. Some of these cars now appear in historic and vintage events. The sight of a 917 or a 512 is thrilling but bears no comparison with the sight, sound and smell of five of each swooping down from that last hill on the Mulsanne straight at Le Mans, then braking hard for the right hander, tails wagging under that hard braking, streams of flame belching out the back on the overrun, followed by the pulse and scream of 5-liter engines as they accelerate away again, the driver just peeking over at the signalling boards.

Photo: Pete Luongo

Driving the 512S

So, I’m not so impressed by the single 512 or 917 showing up at Goodwood or Laguna Seca. But ask me if I’d like to get behind the wheel, and I’d do that on a dark night in an empty stadium with the lights off just to do it!

As it happens, 1006 passed out of the hands of NART in 1972 and through some eleven other sets of hands, American, British and German, having had a restoration in 1993, though the spyder configuration had been altered to berlinetta in 1979. This was not a particularly major event, as the spyder was essentially a berlinetta with the roof panel removed; and some berlinettas ran with the roof panel removed and weren’t spyders! Courtesy of Talacrest and Symbolic Motors, I was able to try 1006 in berlinetta mode, but with the roof panel off, on a damp day on the ultra quick test circuit at Longcross in Surrey.

When one of your dream cars comes along, it takes some effort to stay in touch with the event. Some famous backsides had been in this period 512 seat, handling the small Ferrari steering wheel, experiencing the thunder from the big white exhausts out the rear, feeling the impact of those 550 horses hitting you in the back, struggling to concentrate on Ferrari’s funny little shift gate, two chrome plates, one on top of the other, laid out so you can’t down shift more than two gears at a time!

So here we were, with a multi-million dollar and very historic machine, on big Goodyear slicks (and old ones at that) in the wet, and it was drive time. The car has two big areas of sensory impact. One is the obvious stunning external shape, with those bulging curves at the front and menacing lines sweeping up the tail at the rear. The other is what happens when you switch it on. The noise, assuming you get all 12-cylinders at the same time, which we did, is oppressive and yet seductive. You know you are going to be deaf or at least have that ringing in your ears for hours, but you don’t care. And if you drive quick enough, the sound wall stays just that bit behind you. But the vibration can literally be felt in the eardrums, and it hurts.

Photo: Ed McDonough

The other sights and sensations are also distracting: all those fuel fillers from the period, and the six into two exhaust pipes on either side of the engine protruding through the rear body panel, flanking the overhanging 5-speed gearbox. In spite of my anxiety, the gearbox was not that difficult to manage, and when warm was nothing less than a treat, going up and down being simply a matter of reasonable assertiveness and precision. That’s not hard when you can play music with the gearbox, once you’re running.

Though the first impulses are about protecting the car and yourself from harm, it isn’t long before the ambience gets to you. My eye is drawn continually to the round sweeping lines, which is why the 512S has more aesthetic appeal to me than the faster 512M. The shape is just so much nicer, though not as business-like as either its later version or the Porsche 917. This particular car has a few air intake scoops to take air to the rear brakes, but fundamentally the lines have been retained from the early versions of the 512S, so not only does it feel right, but it looks right.

The overall impression is, as Tony Adamowicz says, of a very rigid chassis. In the damp, this means the tail hangs out. It also means that the front venting brings surface water up to splash on the screen. The cockpit rapidly warms up, so 24-Hours in here would be an ordeal… unless you love this sort of torture. Would I want to drive it night and day, in the wet and dry, with that blast of noise as you push up to 5000, 6000, 7000 rpm?? Do you really have to ask?

Owning and Maintaining a 512S

You can indeed own one, as this car is for sale, but the price is up in the semi-stratosphere, where you would expect it to be. Having said that, you get one hell of a piece of history with a 512. Arguably one of the best pieces of history available, as the 512 is not only a car, but a connection to the best sports car racing many of us will ever experience. You will, of course, have to buy a mechanic with it, as this is not the car to play around with on weekends. 1006 has no recent race history and everything about it indicates it has been well looked after. The engine runs cleanly with no fuss, in spite of a tired battery, meaning the plugs tended to oil up on starting, but they soon cleaned up and the car was surprisingly unfussy. What doing a regular program of vintage races would do to it is another question. This is a car built for long distance racing. Everything about it is reminiscent of the time of the great endurance events, and sadly we don’t have many of those for this car anymore.

Specifications

Wheelbase: 2400 cm.

Front track: 1518 cm.

Rear track: 1511 cm.

Suspension: Front: Independent with coil springs. Rear: Independent with coil springs.

Engine: Horizontal 12-cylinder

Bore and stroke: 87 x 70 mm.

Capacity: 4993 cc.

Horsepower: 550 bhp @ 8500 rpm

Induction: Mechanical fuel injection.

Gearbox: 5-speed and reverse

Brakes: Discs, front and rear.

Weight: 840 kg.

Maximum torque: 51 mkg. @ 5500 rpm

Clutch: Triple plate Borg and Beck

Differential: ZF limited slip

Wheels: Campagnolo 11.5 ” at front, 16 ” at rear

Fuel capacity: 120 liters

Resources

Prunet, A.

Ferrari Sports Racing and Prototype Competition Cars

1983, Haynes Publishing, Somerset, UKISBN – 0 85429338 8

Tanner, H. and D.Nye

Ferrari

1984, Haynes Publishing, Somerset, UKISBN – 0 85429 350 7

Wimpffen, J.

Time and Two Seats—Five Decades of Long Distance Racing

1999, Motorsport Research Group, ISBN – 0 9672252 0 5

The author would also like to thank Tony Adamowicz for his input on this story and Talacrest and Symbolic Motors for the gracious use of the car.