Like so many early automobile manufacturers, the Auburn Automobile Company started out as an evolution of carriage making. Charles Eckhart started a company, the Eckhart Carriage Company, building carriages in 1875 in Auburn, Indiana. As the 19th Century wound to a close, his two sons, Frank and Morris, wanted to try their hand building one of those new-fangled contraptions, the automobile. They knew that carriages were on the way out, and autos were rolling in.

The first Auburn automobile was a product of the Eckhart Carriage Company of Auburn, Indiana. The year was 1900, and the Eckhart brothers, Frank and Morris, built a vehicle that hewed to the times, a single-cylinder, tiller-helmed, solid-tired Runabout. When production hit its stride in 1902, the tires now held compressed air, and the 78-inch wheelbase of the chassis held a 6-horsepower engine. This effort tipped the scales at 1,150 lbs., and set a buyer back $800. In 1904, Auburn built 50 of these, setting the stage for incremental improvements with each year.

Power was bumped up by 12 horsepower in 1905, thanks to the addition of a second cylinder. By 1909, a four-cylinder engine was available in an Auburn, a Rutenber powerplant that generated 25-30 horsepower. While the rear wheels were still chain driven, Auburns were well-built automobiles, if not very exciting. Roads were rudimentary, and durability was paramount. Auburns were durable.

As the years rolled on, Auburn built ever-larger vehicles; the engines had to grow as well. By 1912, a six-cylinder engine was in the line-up, a 41 horsepower in-line Rutenber powerplant. With a frame blessed with a huge 135-inch wheelbase, the Model 6-50 used its tall 37-inch tires to clamber over the ruts. The price for all this movable mass was a lofty $3,000. Four-cylinder models were still in the Auburn line, appealing to more modest tastes with prices ranging from $1,100 to $1,750. In 1916, a trio of engines graced the Auburn line; Series 4-38 using a four-cylinder Rutenber engine, a Series 6-38 equipped with a six-cylinder Teetor powerplant, and the Series 6-40, which used a six-pot Continental. With all of these choices, one would think that buyers were flocking to dealerships, but that wasn’t the case. Sales were soft, and the firm was struggling. Ripe for a takeover, Auburn was snapped up by a group of Chicago businessmen, including William Wrigley Jr., of the chewing gum empire.

With new management, change was soon afoot at Auburn. One of the most visible was the release of the Auburn Beauty-SIX in 1921. An upright, cleanly styled vehicle, it used advanced design features to stand apart from the crowd, including disc wheels, steps in lieu of running boards, and a Continental six-cylinder Red Seal engine, rated at 43 horsepower. Auburn heavily promoted the vehicle across the county, and sales were encouraging, with total Auburn sales exceeding 6,000 units. Between 1919 and 1922, Auburn sold 15,717 vehicles, as first blush an impressive number, but in fact, Auburn was struggling. Management brought in Roy H. Faulkner in 1923 to perk up sales, but that hope was soon dashed. In 1924, the assembly line was bolting together just six cars a day, not enough to keep the lights on.

At this stage in most company’s history, the firm would fade into the shadows. But like a Hollywood feature, a white knight rode in to save the day. This knight was, as Time magazine would describe, a “profane, bespectacled capitalist whose life has been a garage mechanic’s dream” and “an astute, scheming, self-effacing businessman who knows how and where grand parsnips can be found and buttered.” Errett Lobban Cord (E. L. Cord), born in 1894, and possessing a high school education, was a tireless charger who had vision and sales skills sufficient to sell snow to Eskimos. He worked at a Los Angeles, California garage and turned it into a chain of filling stations. He even ran a trucking operation that transported alkali out of Death Valley. By the time he was 21, he’d made and lost $50,000 – three times. In 1919, virtually flat broke, he went to Chicago and went to work at Quinlan Motor Company, which handled Moon automobiles. In a short period of time he rose to become general manager, eventually securing a stake in the firm. He saved up $100,000, and started to look for places to invest it. Enter Auburn.

It was 1924, and the folks running Auburn needed a general manager that could straighten things out. With his success moving Moon automobiles, and his incomparable sales skills, Cord signed on with Auburn as general manager, without pay. But his contract gave him the right to buy the company if he righted the ship and got the bankers off its back. A sizeable problem was in the way though – 700 Auburn automobiles were sitting on the factory’s parking lot collecting dust. They were approaching obsolescence, but Cord felt that with a little lipstick, he could move the metal. By painting many of them in flashy colors, and adding a bit of brightwork, he was able to clear the parking lot of the “New Old Stock.” In doing so, he became a hero to the Auburn board of directors when $500,000 rolled into the company’s coffers. Cord became a vice-president at age 30.

Two years later he was the president. By 1925, sales had doubled, and the following year, doubled again. With 8,500 vehicles sold, for a profit of one million dollars, Cord seemed to have the Midas touch. It helped that the Auburns being offered were all-new. The Model 8-63 debuted in 1925, and it used a Lycoming L-head, straight-8 cylinder engine. The new car was an attractive blend of upscale presence and solid engineering, a mixture that defined Auburn. But Auburn really hit its stride with the release of the 8-88 in late 1925, the engine displacing 276.1-cubic-inches and generating 60 horsepower. By 1928, the 8-88 was chock-a-block with features, such as four-wheel hydraulic brakes, Bijur lubrication, a tough “twist-proof” pressed steel chassis, semi-elliptic front and rear springs, and a three-speed transmission. Atop this engineering prowess, coachwork that teased the eye was fitted. Two-tone paint schemes and a beltline that flowed up onto the hood, tapering towards the nose quickly became an easy way to identify an Auburn. All this class cost $1,695. It was a value-rich vehicle.

Before long, Auburn showrooms were busy. This was a change for most dealers; in pre-Cord days, the dealer body was laughably inadequate. Many dealerships were a simple garage with a single vehicle. Cord traveled thousands of miles by rail and automobile developing an effective dealer body by signing up worthy individuals and cutting loose the deadwood. It was grueling work, but the results were worth it.

Performance was improved with the 1928 debut of the Model 8-115. While the engine displaced the same cubic inches as the 8-88, a Stromberg updraft carburetor helped the new car deliver 115 horsepower. Under the car, a new 130-inch chassis boasted Lockheed four-wheel hydraulic brakes and hydraulic shock absorbers. It was a superb basis to mount superb bodywork on. Auburn had the chance to create something truly special, and they took it. The result was the boattailed speedster.

Boattailed Speedster

Created to make a statement, the boattailed speedster looked long, because it was long. At 180 inches, with room for two occupants and a set of golf clubs, its rasion d’etre was effortless, impressive cruising. With a steeply raked windshield, a pair of side mounted spare tires, and a top that could disappear, Cord had a vehicle with which to do battle with arch enemy Stutz and their Blackhawk. Before you could say Auburn’s slogan “The Car Itself Is The Answer,” the speedster was thrown onto the battleground of competition. From speed runs on the sands of Daytona Beach to tackling Pikes Peak (winning the Penrose Trophy), the speedster was engrained in the minds of America as a dashing, sporting vehicle that proved itself under the harshest conditions. And it could be in your garage for thousands of dollars less than a Stutz.

Sales skyrocketed, with more than 22,000 Auburns sold in 1929. Cord continued to push the company, with the Model 120 released in 1929, and 1930 seeing the Model 125 debut. These models were essentially Model 8-115’s with a touch more power and a new nameplate.

In many ways, 1929 was a special year for E. L. Cord; he formed the Cord Corporation, which had under its umbrella a wide range of companies that Cord had by then purchased. These included Lycoming Motors, Limousine Body, Central Manufacturing Company, and Duesenberg. A front-wheel drive automobile bearing his name and fitted with many advanced features even hit the street in ’29.

However, late in 1929, the Depression also hit the street. Auburn sales dipped to 13,700 units in 1930, but by mid-1931, they’d rebounded strongly. In that year, 28,103 Auburns went to good homes, while more than $3.5 million profit went to the Cord Corporation. Auburn was 13th in retail sales. What Depression?

In 1931, Auburn dropped the 6-cylinder models and the 8-125 series, putting all of their production and marketing chips on a single vehicle, the eight-cylinder 8-98. Auburn delivered an impressive amount of automobile for the money, as Business Week noted “it was more car for the money than the public had ever seen.” Its straight-8 engine cranked out 98 horsepower at 3,400 rpm, and sat in an exceptionally strong “X” brace in the beefy frame. Prices ranged from $945 to $1,195 for the standard models, $1,195 to $1,395 for custom models. Auburn offered seven versions within each model line. Dealers tarted up each in-stock car, yet even with a full slate of bolt-on accessories, owners knew that they were getting a lot for their money. Yet Auburn had even more to reveal.

Twelve is Too Much

In the 1930’s, something of a race was underway for multi-cylinder models among manufacturers. V-12 engines were a sign of prestige, and some cars makers, for example Cadillac, even offered V-16’s. Auburn, and by extension E. L. Cord, couldn’t resist competing on this turf, so in 1932 the Auburn V-12 was introduced. This powerplant displaced 391-cubic-inches and was rated at 160 horsepower. The eye-opener was the price; a two-door coupe with this big engine cost just $975. But the timing couldn’t have been worse.

The Great Depression was picking up steam. In 1933, American automobile production was just a quarter of its level from 1929. Great automotive marques were in trouble, serious trouble. Auburn wasn’t exempt from the hardships sweeping across the country. E. L. Cord no longer had a hand in the operation of Auburn, as he first moved to Chicago, then Los Angeles. By the beginning of 1934, he would be living in England. He tapped an associate, Lou Manning, to run Auburn in his absence. Soon a new president, W. Hubert Beal, was installed, but Beal soon realized that the job of restoring Auburn was far more difficult than anticipated. Manning, still on the payroll, was tasked with keeping an eye on Beal, an arrangement that pleased neither man. In this tense climate, a new Auburn model was created.

It was hoped within the company that 1934 would be the year that saw a renewal of Auburn’s fortunes. Such a reversal was needed; sales in 1933 were a dismal 6,000 vehicles. A 6-cylinder engine was put back in the line-up, the 210-cubic inch Lycoming that had been dropped in 1930. By the end of the year, the V-12 was gone. The straight-8 engine came in two levels of tune, a 100 and 115 horsepower rating. Yet the biggest response came from the new-for-’34 bodywork.

Reflecting the evolving designs of the era, streamline styling was introduced in the new Auburn. The nose was sloped, the fenders had more curvaceous contours, and the hood wore a trio of arcing vents. The heads of Auburn hated it. The stylist that penned the car, Alan Leamy, was sacked, and Manning brought in Duesenberg president Harold T. Ames to restore Auburn’s look. Fortunately for Auburn, Ames brought with him to Auburn the talented stylist Gordon Buehrig and Duesenberg’s chief engineer, August Duesenberg. In the summer of 1934, E. L. Cord returned from England to find Auburn mired in a mess. The people he had installed to run the firm had taken their eyes off the ball, and the company was lurching towards a bad end. Strong action had to be taken. The aim was to create an image building model that would restore traffic to Auburn showrooms and return the company to profitability. At least that was the plan.

Supercharged Speedster

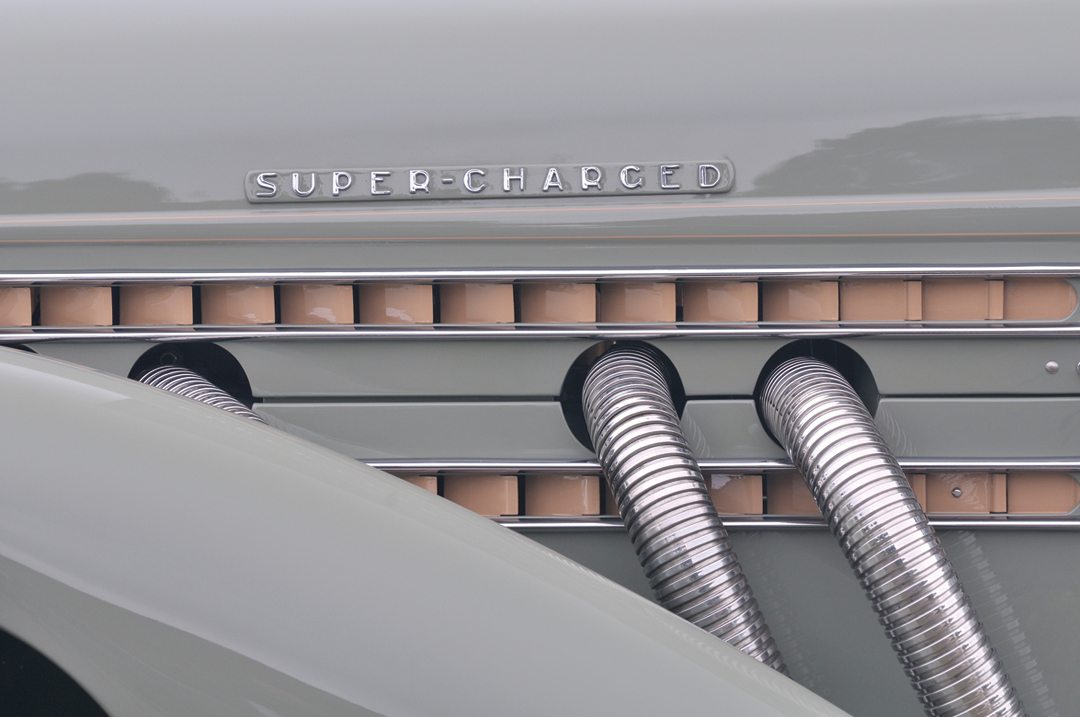

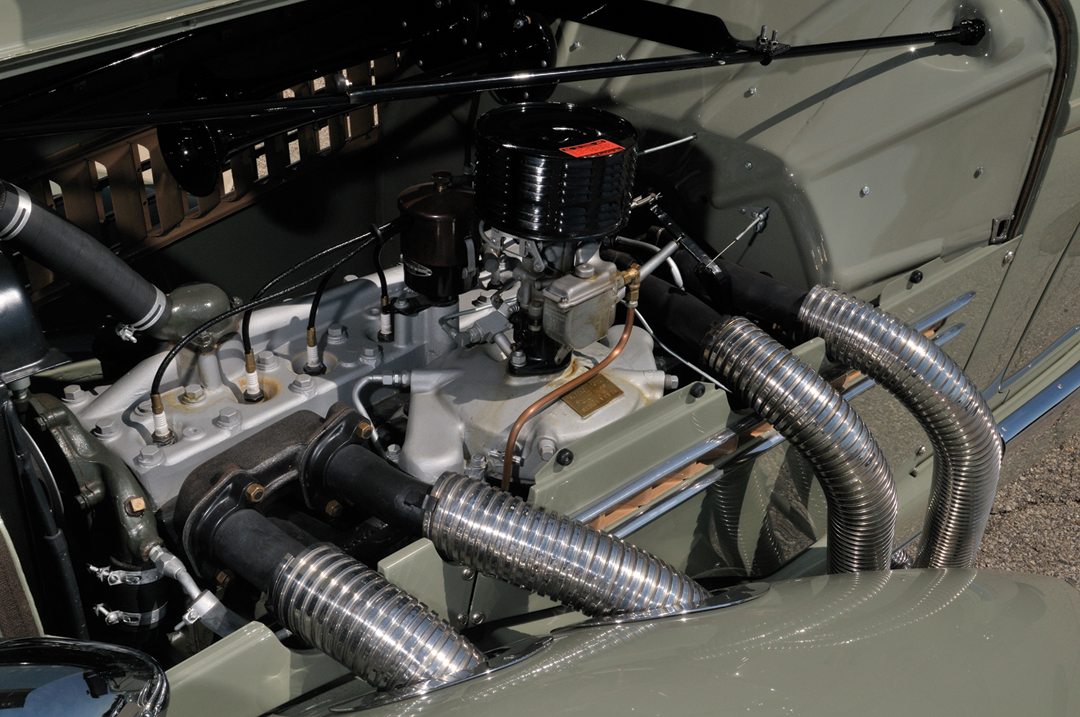

Auburn had offered the luscious boattailed speedster model for quite some time, equipped with the V-12. But it didn’t sell well. So for 1935, the speedster body was refreshed by Buehrig with an extended tail, smoother pontoon fenders, the removal of the running boards, and a cleaned up front end. It was released as part of the 851 model line, with a new powertrain sitting in a frame with a 127-inch wheelbase. The heart of this halo car was under the hood, a Lycoming straight-8 engine displacing 279.2 cubic inches. It used a bore of 3 1/16-inches and a stroke of 4 ¾-inches. The engine block was cast iron, and the head was aluminum. With a Schwitzer-Cummins supercharger mounted on the left side of the engine, power was rated at 150 horsepower at 4000 rpm, and 230 lb-ft of torque at 2750 rpm. This supercharger spun at six times crankshaft speed, and pulled air through a Stromberg downdraft carburetor.

The Auburn 851 speedster boasted another feature that allowed it to break 100 mph, a Columbia electric, dual ratio rear axle. Utilizing this feature allowed the Speedster to nudge into triple digits on the speedometer. The final drive ratios were 5.1:1 in low, 3.47:1 in high. A pre-selector lever on the steering wheel controlled the ratio.

Auburn, for model year 1935, offered a wide range of other models—18 in all! The speedster was the crown jewel of the line-up, and rightly so since it commanded a top price. Yet for $2,245, it was, like Auburns of years before, a lot of car for the money. Every 851 speedster wore a tag on the dashboard, signed by Ab Jenkins or Wade Morton, attesting that the vehicle had passed 100 mph. In an era when 45 mph was considered a good clip, passing the ton was special. But even the bean counters at Auburn should have realized that speedsters weren’t putting a dime into the company coffers. Each speedster lost the company about $300. Approximately 500 supercharged speedsters were built in 1935-’36. The only difference between the two years was the change in model designation from 851 to 852.

Sales were weak in 1935, sliding into sad. Total Auburn output for 1935 was 9,645 automobiles, and the following year, just 4,830 Auburns were built before the factory shut its doors in October, 1936. Auburn was gone, but with the 851/852 supercharged boattail speedster, the company’s swan song was its most beloved model.

On the Road

At first glance, when approaching this 1936 852 SC, one is struck by the vehicle’s stance. For an automobile with a sizeable 127-inch wheelbase, the speedster is both massive and sleek. Gordon Buehrig took the 1934 speedster body, with its shortened tail, and by lengthening and reshaping it, created a vehicle with superb proportions. The 852 speedster looks like it’s in motion before the engine even starts. With its laid-back front end, steeply raked windshields, exhaust pipes flowing from the left side of the long hood, and sweeping pontoon fenders, it reeked of speed. Even the leading edge of the doors exhibited a flowing line. A discrete use of chrome highlighted key styling elements without creating a stripped look. It’s said that the mark of a good designer is knowing when to lift the pen, and Gordon Buehrig knew when to step away.

The 851 SC is a two-seater vehicle, and it makes no apologies. Designed for high-speed cruising and to see and be seen in, it has charisma to burn. Opening the rear-hinged door reveals an interior that is inviting, intimate, and lushly trimmed. With the top raised, my 6’4” frame took a bit of Gumby-like contortions to slip behind the wheel, but once in place, I found that I had a surprising amount of leg room, and the large steering wheel was close enough to comfortably grasp, yet far enough away to avoid feeling claustrophobic. The view out the twin windshields is dramatic; the long hood is flanked by the peaks of the front fenders and headlight fairings. Vision rearward is limited to a rear window about the size of a license plate. But you don’t get behind the wheel of an Auburn SC speedster to worry about what’s behind you.

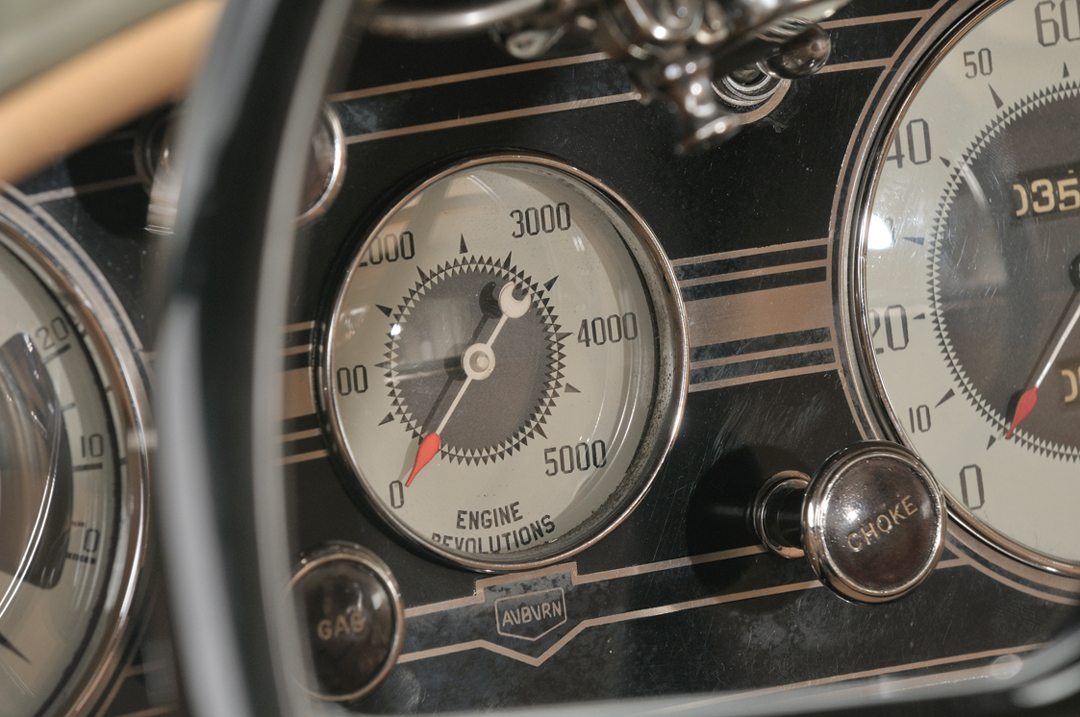

The dashboard is a wonderful example of Art Deco mixed with functionality. Directly in front of me is a tachometer, its red-tipped needle poised to reach towards the upper half of its range. No redline is posted; Speedster drivers were presumed to be adults and possess enough common sense to shift the transmission when they felt it appropriate. To the right of it is a speedometer, to the left are secondary gauges in a circular housing. The ignition switch is to the right of the steering column, and the starting procedure is straight forward. After pushing in the clutch (firm, but not abusive), I pull the choke knob, then push the ignition switch down to engage the starter, then flick the starter lever in the opposite direction once the engine has started. The straight-8 quickly settles into a smooth, mechanical vibration, giving off a low exhaust rumble. I tap the throttle, and I’m surprised how quickly the tach needle swings. As the rpm’s climb, busy sounds start to make their presence known in a delightful fashion, not raucous, but I’m aware that on the other side of that firewall is a controlled series of explosions.

I reach down and push the parking brake forward, releasing it. The long shift lever slips into first gear. A whisper of gas, a gentle release of the clutch, and the big Auburn is underway. First gear is well matched to the engine, and soon I need second gear. I move the lever into place, and I’m struck by the buttery feel of the transmission. In all of my years behind the wheel, I’ve never felt a gearbox so silken. It’s a joy to change gears, a task that I look forward to. It’s hard to believe that bits of hard metal can move together so utterly smoothly.

As the pace increases, the steering feel comes through my fingers. I can sense that the tires are rolling over less than a glassy road, and the wheel dances gently. But it’s no problem to keep the prow pointed in the right direction, and as a curve comes up, the wheel weights up nicely as I feed it into the turn. With the long wheelbase, it’s clear that this is not a racecar; it feels very substantial without feeling ponderous. The Auburn feels simultaneously very classy and very sporty. Reactions from people on the side of the road range from total unawareness (ages 30-45), huge smiles (ages 65+), to seeing a UFO (ages 5-15). In a world of Blandmobiles, I’m in a four-wheeled space ship decades ahead of its time, and this time.

As I put the village in my mirror and the road turns empty, it’s time to see what’s under the huge hood. I’m in second gear, and I give the Auburn a bit of whip. The exhaust note sharpens, and over the low register I hear a faint whining from under the hood, growing in pitch. The supercharger is making its presence known in two ways; I can hear it, and my body can feel it as I’m pushed into the seat back. The 852 SC is not, by contemporary standards, a fast car. 0-60 mph requires 15 seconds. But in 1936, this was real performance. With a top speed of 100 mph, the 852 SC will cruise at today’s highway speeds without effort. Slipping into third gear, flicking the switch for the dual ratio rear axle drops the revs to a comfortable level. The 852 SC is now in its element, effortlessly devouring long stretches of blacktop. At 60 mph, the wind is swirling around the interior, and the cacophony of engine, exhaust, and road noise meshes into a melody of speed. Few of today’s cars can touch the sheer sensory magnificence that is the 852 SC at speed.

And the 852 SC can stop as well as go. With its four-wheel hydraulic drum’s, using the binders requires a bit of attention. Anyone with experience in a vehicle with drum brakes knows that every time the brake pedal is pushed, it’s anyone’s guess exactly where the car is going to go. But the 852 SC is no more a handful than other period cars, and actually, it’s better than most in the braking department. Looking far down the road and anticipating conditions is the surest way to avoid trouble.

Too soon I’m back in the garage. I tap the ignition switch, and the big eight falls silent. I sit still, listening to the ticking of the engine as it cools. It’s been a treat, a true joy to drive this car. Auburn built many cars in its nearly 40-year span, but only one model continues to thrill; the 852 SC Boattail Speedster. Auburn’s swan song was its masterpiece.

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis: X-type ladder frame

Wheelbase: 127-in.

Track: 57-in. front, 62-in. rear

Weight: 3752.3-lbs.

Suspension: Rigid axle, semi-elliptic springs, hydraulic shock absorbers 8 cylinder in line. 2 valves per cylinder, Side-valve

Displacement: 4585-cc (279.8-cu.in.)

Bore x Stroke: 77 mm x 120.6 mm

Carburetion: Single downdraft Stromberg

Compression: 6.5:1

Horsepower: 150-hp @ 4,000 rpm

Gearbox: Three speeds and reverse, Dual Ratio differential

Brakes: Drums, hydraulic, four-wheel