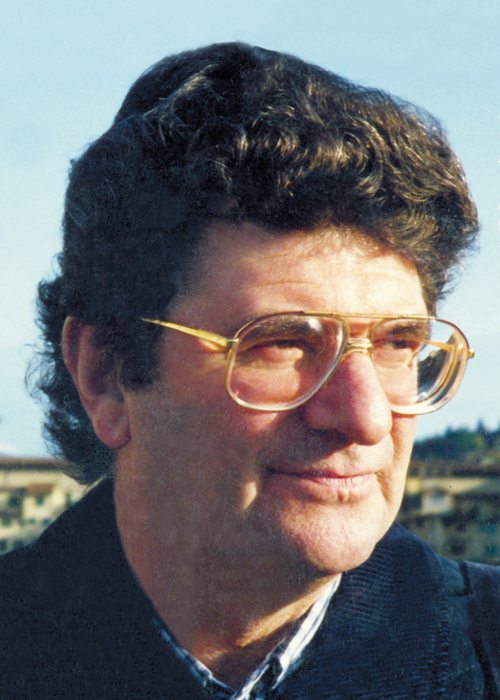

Like Mario Andretti and Nigel Mansell, Emerson Fittipaldi is one of the elite. A driver who has won the Formula 1 World Championship (twice) and the CART title with a record in both—that reads like any self-respecting Walter Mitty’s wish list. He won 14 Grands Prix—not to mention non-title “oddments” like the Race of Champions (Brands Hatch), the International Trophy (Silverstone), the Italian Republic GP (Vallelunga) and the President Medici GP (Brazil)—and 22 CART races including two Indianapolis 500s in his long and extremely distinguished career.

On top of that, he set a record in 1972, at 25 years old, by becoming the youngest driver ever to win the F1 world title. A record that stood for 33 years, until 24-year-old Fernando Alonso came along in 2005 and broke it.

Emerson was a genius behind the wheel, overflowing with natural talent spiked with a keen strategic mind, with which only a handful of drivers have graced the motor racing circuits of the world. Varzi, Fangio, Senna, Schumacher, some of the sport’s greatest to which Fittipaldi’s name can be added without fear of contradiction.

Fittipaldi was born into a racing family in Sao Paolo, Brazil, as his father Wilson Senior and his mother Juzy both raced production cars after the Second World War. And Dad was a much respected Brazilian motor racing journalist, who later guided his youngest son’s career for some time.

Like Fangio, the young Fittipaldi started work as a mechanic. He first flirted with motorcycle racing before finding his feet with karts and Formula Vee cars, built by a company run by his brother Wilson Junior. Emerson made his way to Europe in 1969 and quickly attracted attention with his victorious march through the lesser formulae. So much so that he was signed by Colin Chapman for a full F2 season in 1970 and ended up 3rd in the European championship, which was won by the late Clay Regazzoni.

Frank Williams tried his damnedest to sign Fittipaldi to drive his de Tomaso, after Piers Courage was killed at Zandvoort, but it did not happen. Crafty old Chapman had the Brazilian locked up in a contract not even Harry Houdini could have got out of. By way of encouragement, the Lotus boss gave Emerson his first Formula 1 outing in a 49C at the 1970 British Grand Prix and the youngster used it to finish 8th: two weeks later, he scored his first F1 points with a 4th in Germany. Then disaster struck: Lotus’s number-one driver Jochen Rindt was killed practicing for the Italian GP at Monza in September and his teammate, John Miles, was becoming disenchanted with F1. This pitched Fittipaldi right into the thick of it as, effectively, the Lotus number one at the tender age of 23. The young man soon showed he could handle the job by winning the U.S. Grand Prix at Watkins Glen in a Lotus 72 a fortnight later. He went off the boil in 1971, but 1972 was a completely different story—Fittipaldi became world champion. He dominated the European F1 scene with victories in Spain, Belgium, Britain, Austria and Italy to take the title away from 1971 champion Jackie Stewart with 61 points to the Scot’s 45.

After a rather uncomfortable 1973 with his new, exceptionally competitive teammate Ronnie Peterson—Fittipaldi won three GPs to the Swede’s four—Emerson surprised everyone by signing with McLaren for big bucks and became the 1974 world champion with wins at home in Brazil, Belgium and Canada. Niki Lauda proved all but unstoppable in the Ferrari 312T in 1975, although Emerson did manage to win in Argentina and Britain to finish 2nd in the championship in the slower Cosworth-engined McLaren M23. Then he announced he was leaving Woking to join his brother’s new F1 team, which had risen from the ashes of Walter Wolf Racing. But out of 103 starts, the best the Copersucar (Brazilian sugar) sponsored squad could do was Emerson’s 2nd in the 1978 Brazilian GP. After that, they achieved very little in Formula 1, resulting in the sponsorship drying up and the team faded away by the end of 1982.

But Emerson was still very much a talent and, like many other F1 refugees, he set sail for the United States, where he started in IMSA before gravitating to CART in 1984 and the beginning of the second phase of his stunning career. He took his time finding his feet in North American single-seater racing before scoring his first victory after 15 months in a March 85C-Cosworth at the Michigan 500. That was it, until his win at Elkhart Lake in October 1986, after which 1987 brought two more CART successes in the Cleveland Grand Prix and the Molson Indy at Toronto.

Fittipaldi left Patrick Racing for Penske in 1989 and that is where he astonished everyone. He won the year’s CART championship with five victories—one was the Indianapolis 500 and three were subsequent races in succession—in the Penske PC18-Chevrolet. Despite the best efforts of talents like Michael Andretti, Al Unser Jr. and Bobby Rahal, a year never went by between 1987 and 1995 without Emerson earning a ride to victory lane. It was a period in which he won 20 races including the 1993 Indy 500—a success he famously celebrated by drinking orange juice instead of the traditional milk.

Seven months after his 50th birthday in May 1996, Emerson was still competing in Champ Car when he was seriously injured in an accident at the Michigan International Speedway, and that brought his phenomenal career to a close. Worse still, while recovering from the accident, he was flying his micro-light airplane over his orange grove estate near Sao Paolo in September 1997, when the aircraft lost power and fell 300 feet to the ground, causing him serious back injuries.

Emerson did return to Champ Cars as a team owner in 2003. He also made a surprise comeback behind the wheel in the Grand Prix Masters race at Kyalami, South Africa, in 2005. There, he finished 2nd to Nigel Mansell, the man he narrowly beat to take his second Indy, and gave us all a stylish reminder of one of the most outstanding careers in motor racing history.