When the farm owned by Helena Neethling’s father in the Riviersonderend district, about 100 miles due east of Cape Town, South Africa, went bankrupt in 1927 the young woman had no intention of remaining in the area. Nor, when she decided to take up a teaching post in Greytown, Natal, did she imagine that she would one day produce a son who would design a famous sports car, as well as an innovative workbench that would sell by the millions world wide. Nor did she imagine that her son would be awarded an OBE. Such thoughts must have been the furthest from the mind of a young woman intent on establishing a new career far from home.

In Greytown, Natal, about 1000 miles from home, the plucky Afrikaans (derived from Dutch) speaking farm girl met and married bookkeeper, Cyril Hickman. They produced five children and the second son, Ronald Price, was born on October 21, 1932.

At Greytown junior and senior schools the young Hickman displayed a natural musical talent and became a competent pianist and violinist. At age 13, he became organist in the local Methodist Church and by the time he turned 17 he was an Associate of the Trinity College of Music, London, with a Pianoforte Performer’s Diploma.

The entrepreneurial young Hickman was also passionate about cars, carving models from pieces of wood and drawing and painting cars, which he sold to the owners to earn extra pocket money.

After leaving school he joined the Department of Justice in Natal to train as a magistrate. For the next six years he studied law, attended cases in various Magistrates Courts and carried out civil administration of all kinds.

However, Ron soon decided that he was more interested in cars than a law career and like many young South Africans headed for the Northern Hemisphere to gain experience in a wider world. Consequently, at the end of 1954, aged 22, he borrowed £100 from his father and set sail for England aboard the Winchester Castle. Like all good South Africans, he headed for Earls Court where the Overseas Visitors Club (OVC) was a draw for hopefuls from the Colonies, in particular Australia and New Zealand.

Thanks to his musical background, Ron knew but one name in London, Boosey & Hawkes in Regent Street, the world’s foremost manufacturer of brass instruments and drums and classical music publisher. As his funds had dwindled to a mere £34, Ron needed a job and they seemed the first logical port of call. As luck would have it there was a vacancy in the accounts department and the young Colonial was asked to report to the appropriately named Miss B Sharp.

After six months, he heard that Briggs Motor Bodies, in Dagenham, had placed an advert calling for clay modellers. Since the location of the company indicated a connection with Ford, Ron applied. Fortunately, he had made two novel scale model cars in his spare time and took them along for the interview. One was Ron’s idea of what the next Morris Oxford should look like and the other a stylish Bentley. After an initial turning down, Briggs contacted him later and offered him the job.

Shortly after joining Briggs, Ron found himself in hot water. He had already contracted to cover the Earls Court Motor Show for the South African “Outspan” magazine and Colin Neale, Ford’s chief stylist, seconded to Briggs, became concerned that Hickman was a Fleet Street spy and that all Ford’s secret new designs would be leaked. Fortunately, the young South African was able to convince his boss that this was not the case.

Then he had a lucky break when Standard-Triumph head-hunted several members of Ford’s design team. Convinced that Hickman, who had shown promise, would also go, Neale offered him a job as stylist and a three months in-house training course under the guidance of Eric Archer ensued. This was quite an achievement for a young man without any formal qualifications.

Just as Ron was being trained as a stylist, the Austin-Healey Sprite was being developed and this prompted Neale to think in terms of an Anglia 105E-based sports car primarily for the American market. Hickman was asked to work on the project “on the quiet” since Neale doubted that the funding for the project would be approved by the Product Planning Committee, headed by Terry Beckett, later to become Sir Terrence for services to the motor industry.

The styling was radical with mid-ship fins forming the B-posts and which supported the ‘Targa’ top (nearly 10 years before Porsche). Plastic moulded bumpers were to be incorporated, as well as a reverse slope rear screen with wind down glass. When the product planners were eventually shown the project it was canned. The feeling was, possibly correctly, that an English Ford sports car wouldn’t sell in the U.S. and that well-known British cars, like Austin-Healey, MG and Triumph, already had a foothold on the other side of the Atlantic— particularly in the lucrative Californian market.

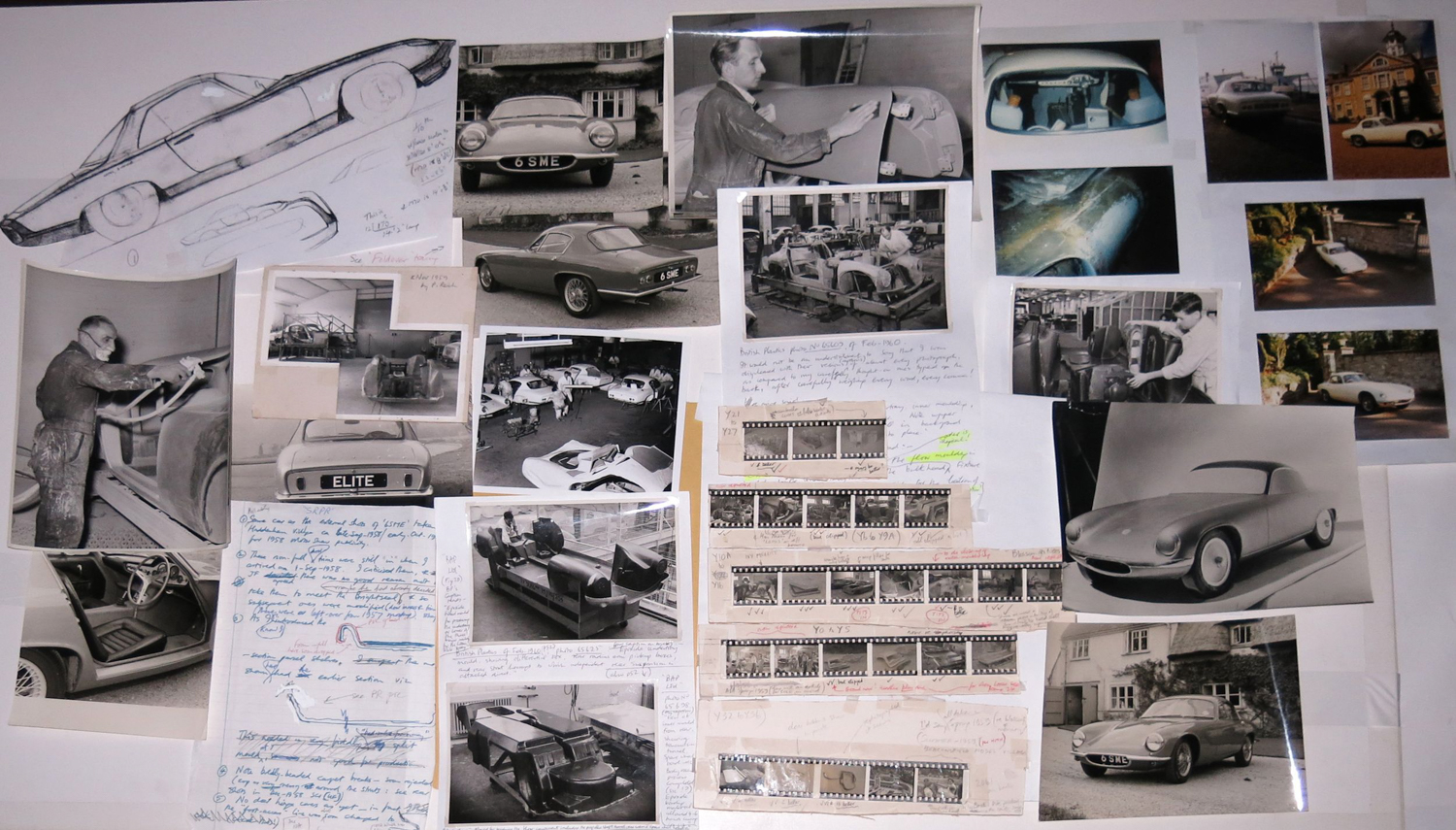

During his three years at Briggs, which during that time had became a wholly owned subsidiary of Ford, Ron worked on the Anglia 105E, the Consul Classic, the Classic-Capri and the Zephyr/ Zodiac Mk111 range. After meeting Colin Chapman at the 1956 Earls Court Motor Show, he was asked to submit ideas on the proposed Elite, to be based on and influenced by the Lotus 11. Designer Peter Kirwan-Taylor had already submitted his design but Chapman was not quite convinced. He felt he needed further input and when he asked Ron to visit him at Lotus HQ he took along two colleagues from Ford, New Zealander John Frayling and Peter Cambridge. Frayling, who in Ron’s opinion, was the world’s best sculptor/ modeller, agreed to build a model on a part-time basis. Ron offered his own ideas and from this team effort the Elite was born.

Ron eventually joined Lotus some two years later in 1958 and his first task was to get the delayed Elite into production. Many customers had already paid deposits and if cars weren’t built and delivered Lotus would have been in a spot of bother. Under Ron’s guidance Elite production got going and it wasn’t long before he was appointed director and general manager of Lotus Developments.

On April 4, 1959, he married fellow Natalian, Helen Godbold who was nursing at a London hospital, with John Frayling as the best man. Three children Karen, Marcus and Janeen followed.

Ron’s next project for Lotus was to design and develop a two seater, the S2 (Sport 2) as a replacement for the non-profitable Seven. Colin Chapman had proposed it be an open-topped car with monocque in GRP.

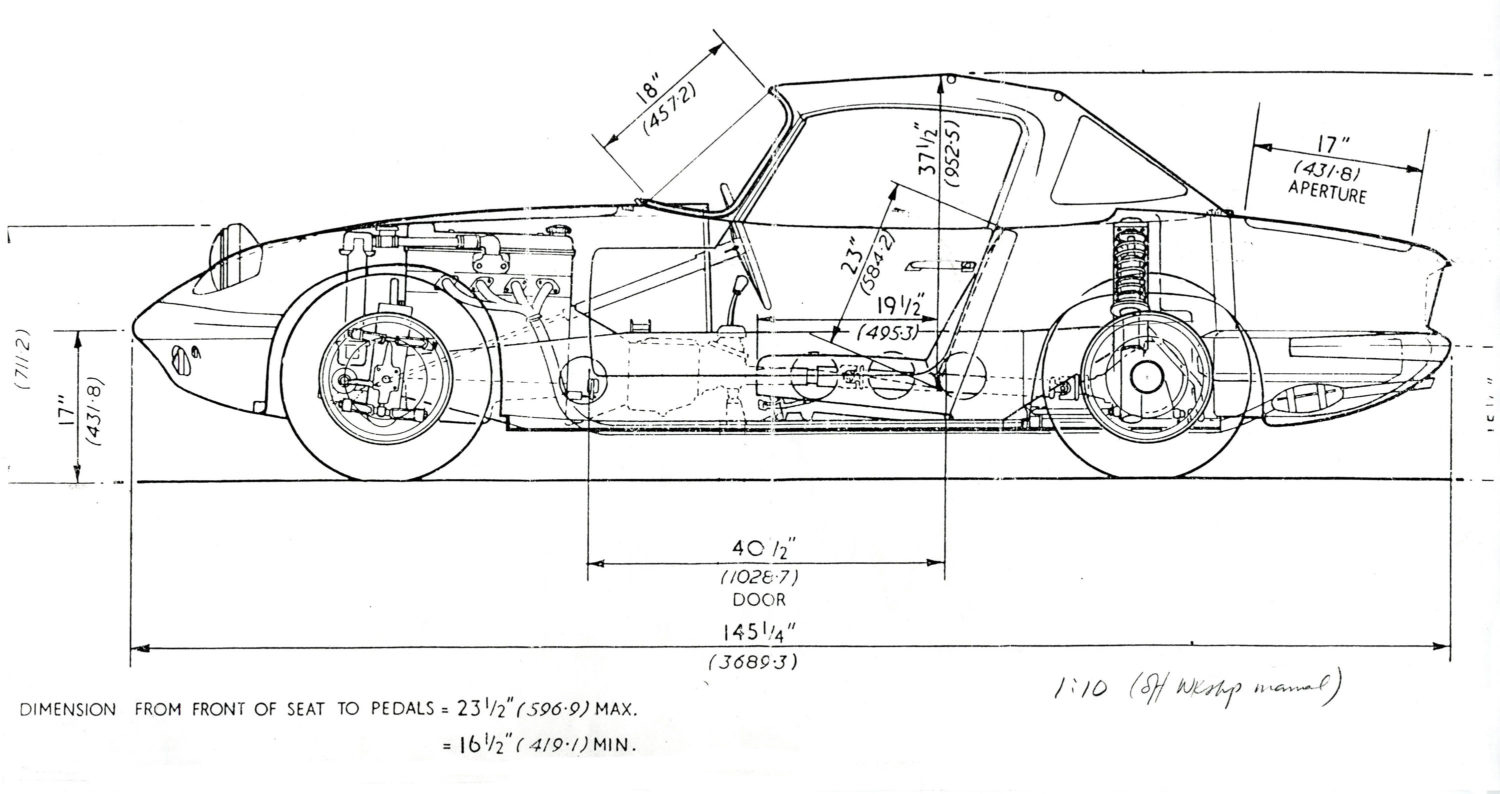

The rather basic Austin-Healey Sprite rival soon progressed into a more sophisticated car. Chapman had suggested a flat windscreen and side screens but Ron gave it a curved windscreen and wind–up windows with counter balance mechanism from the Austin London taxi. Ron then brought into the picture the moulded bumpers intended for his original Ford sports car and retractable headlamps were also added. Suspension was to be fully independent and disc brakes were to be fitted all round. The fibreglass body was a unique one-piece ‘Unimould’ creation which was fitted on to the chassis by 16 bolt fixings, using special Hickman designed bobbins to distribute the load evenly into the fibreglass.

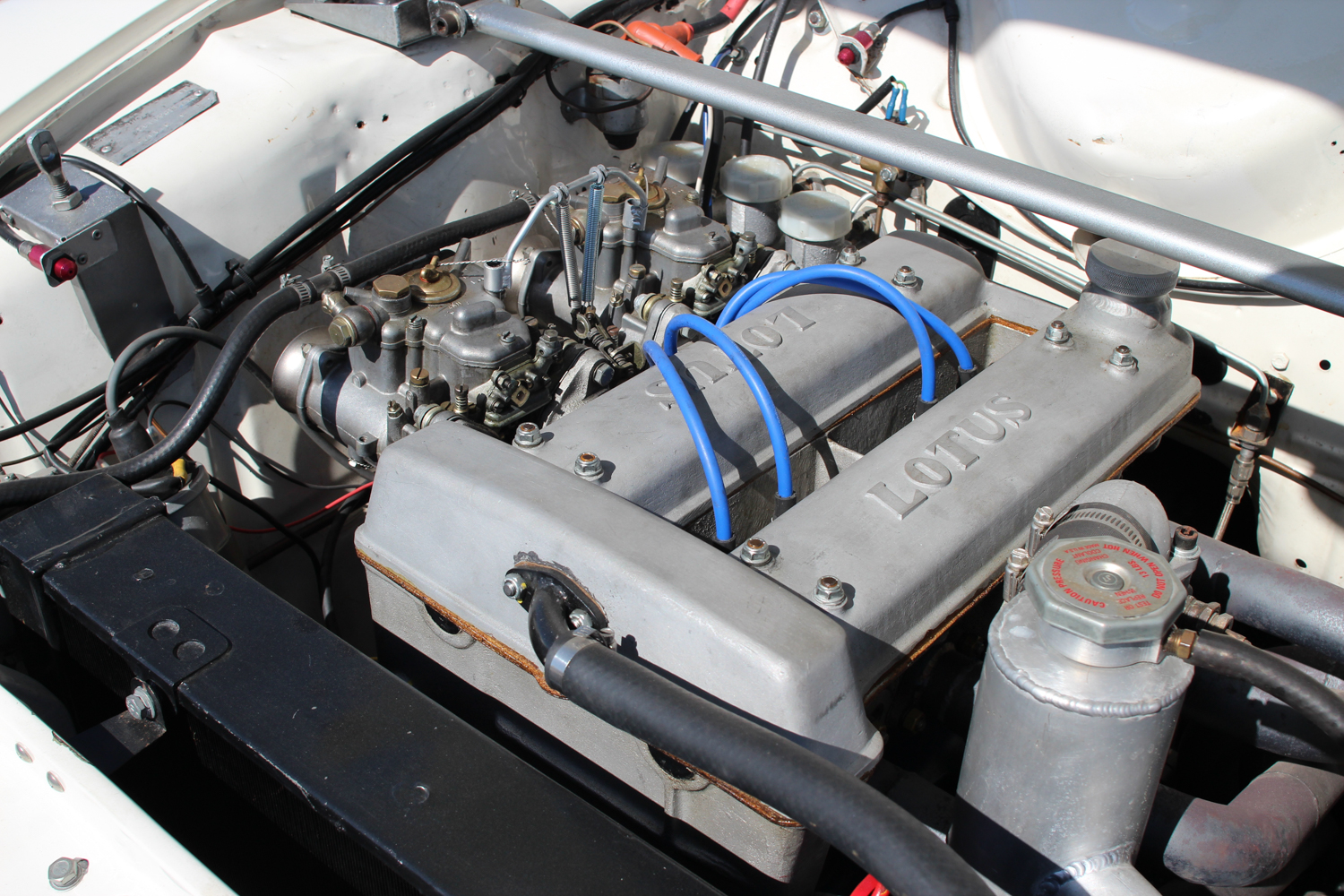

The backbone chassis was constructed from pressed sheet steel to form an elongated X and the substantial center spine gave the unit massive strength A standard Anglia 105E, 997-cc unit was intended but was soon replaced by the 1500-cc Classic engine which was later enlarged to 1600-cc and fitted with a unique Lotus DOHC head designed by Harry Mundy. Ron named the car the Elan, which followed Eleven and Elite and triggered subsequent Lotus names beginning with the letter “E”.

Colin Chapman had discussions with Ford to market the Elan through its dealer network but when some heavyweights from the Blue Oval heard about the pending deal they stopped it. It was Ford only from Ford dealers and intruders were unwelcome, particularly those with fibreglass bodies! Understandably, Chapman was devastated.

Two issues then dovetailed to the advantage of the innovative Chapman and Hickman duo. Ford appointed the lateral thinking Walter Hayes as its PR director with the express instruction to liven up Ford’s conservative mass-produced family car image.

Hayes realized that the Mundy designed DOHC had great potential and saw Lotus as a joint venture partner to assist Ford in driving its new marketing program forward. Chapman felt that the engine should be fitted in the Anglia but Hayes told him of the forthcoming, bigger Charles Thompson-designed Cortina and felt that the engine would be better suited to the new Ford model.

There was much excitement at Lotus when a Cortina was delivered under wraps before it had been announced to the world at large. Ron vividly recalled an excited Chapman running up the stairs to ask him to come and have a look at the new Ford. Work on the Lotus version started immediately and the first improvement of several was a new dashboard with instruments taken from the Elan dash and front quarter bumpers from the Thames van.

A few months later the new engine had a great début when Jim Clark’s Lotus 23 literally ran circles round the opposition at the Nürburgring. This successful beginning led to a deal for Lotus to build the Lotus-Cortina which went on to become a legend thanks largely to the sideways, three-wheeled antics of Jim Clark, Jackie Stewart, Sir John Whitmore, Bob Olthoff and some other well-known drivers. Lotus had OE parts supply status from Ford and the two companies, one Goliath and the other David, enjoyed a mutually beneficial relationship. It also laid the foundation for Ford’s major involvement for the next many years in motorsport including the GT40 and the highly successful DFV Grand Prix engine.

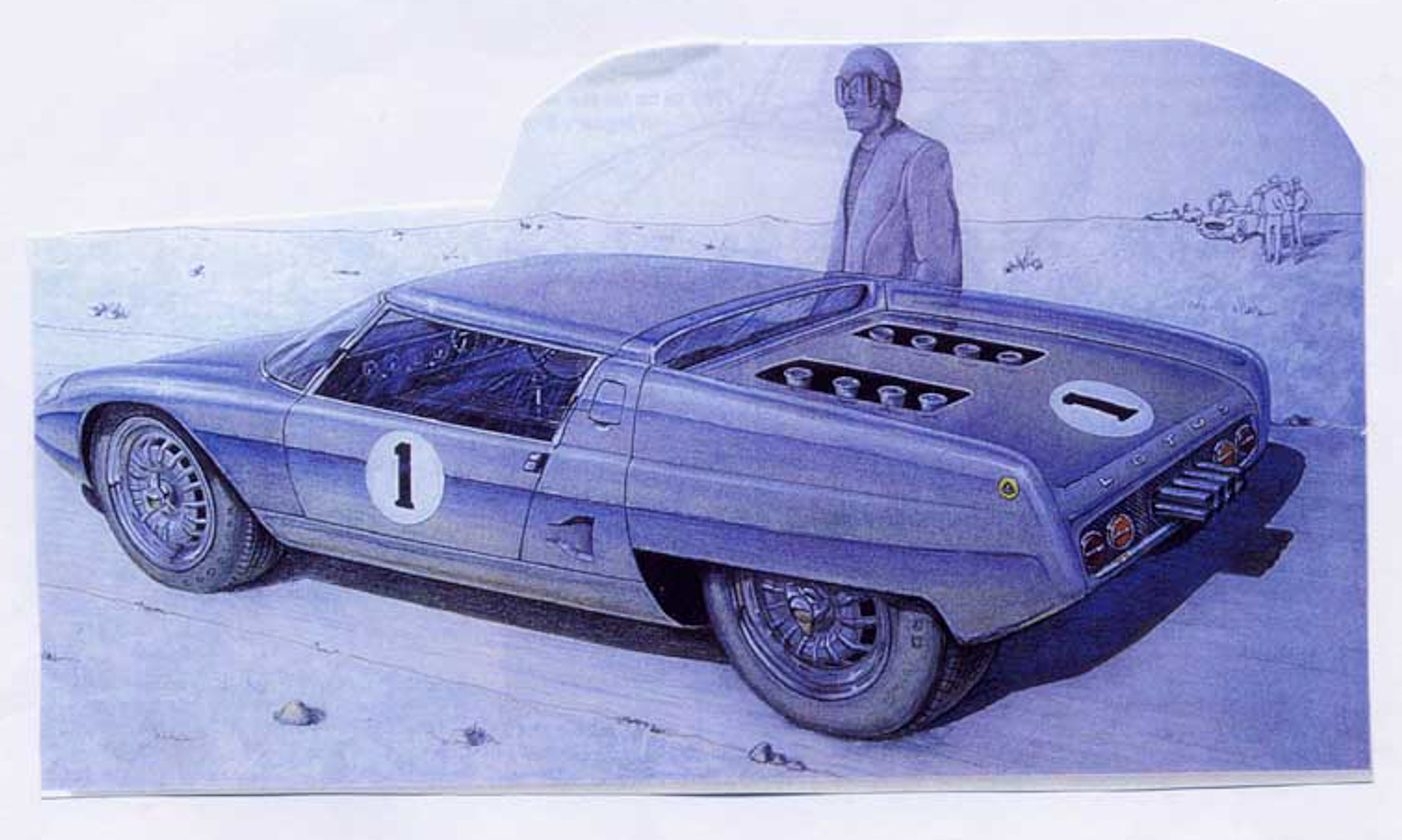

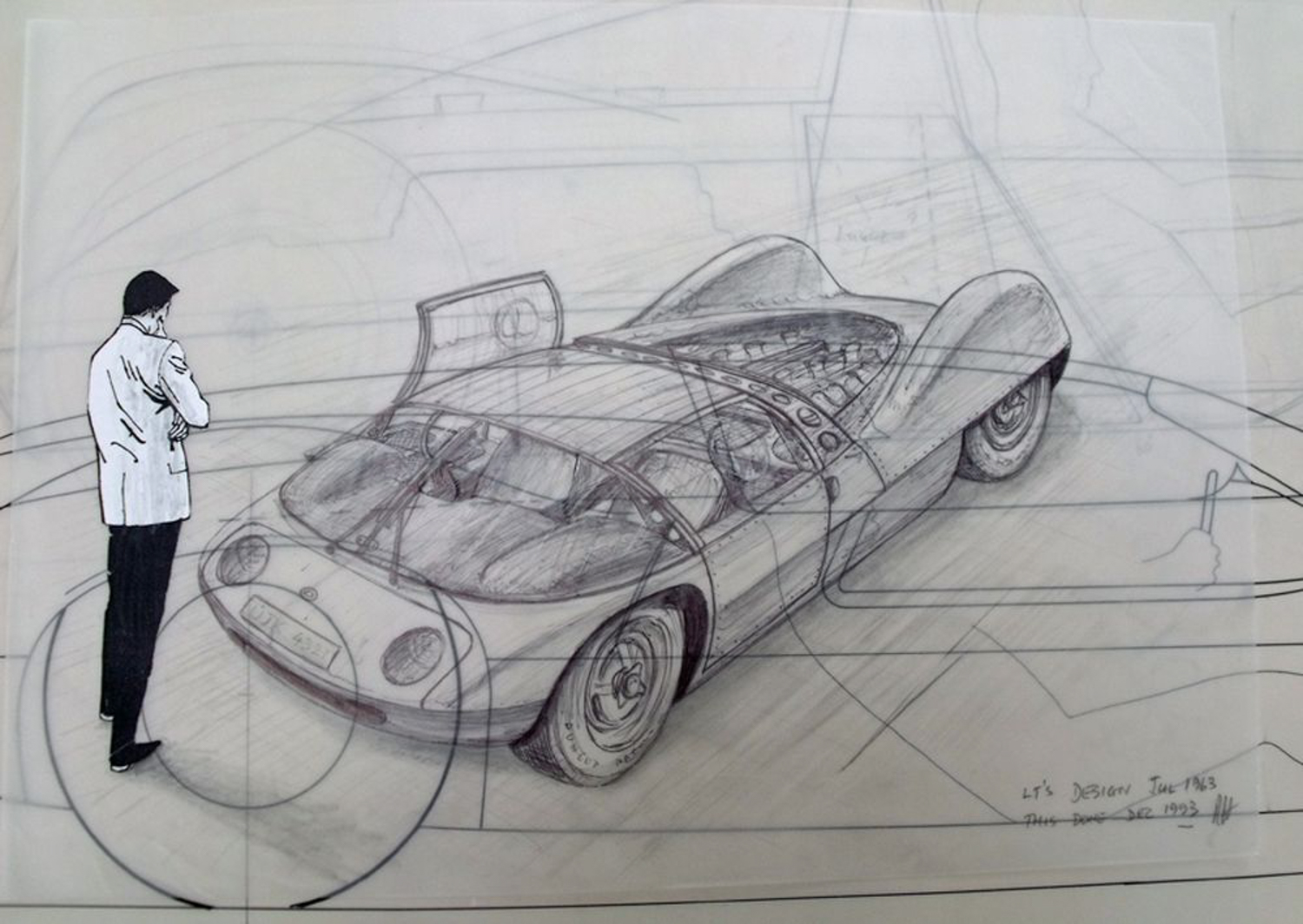

Following the successful launch of the Elan, Ron started work on the stretched Plus 2 version with rear seats. At that time, in 1963, to coincide with Ford’s future plans, Ron had produced a concept drawing of a mid-engined Ford V-8 powered Lotus. Ford, as part of its intended, new ‘sporting image’ wanted to build a racing sports car capable of winning the prestigious Le Mans 24 Hour. Rather than re-invent the wheel, Henry Ford offered to purchase the Ferrari company but the ‘Old Man’ couldn’t stomach the thought of a Ford-Ferrari as the cars would be known. Nor did he welcome hordes of Ford investigative bean counters invading his territory. In the end the offer was turned down and in a huff Henry had to go back to the drawing board. Ford management accepted the fact that their own people in the U.S. had neither the ability, experience or knowledge to build sports racing cars and that the Brits were ahead in the race. British companies Cooper, Lola and Lotus were short-listed as likely partners in view of their collective successes. As Coopers had neither the facilities nor the resources they were eliminated. Ford felt that Colin Chapman was a maverick with his own agendas and he too was dropped. That left Eric Broadley, who had already built a Ford powered, mid-engined car dubbed the Lola MK6, styled by John Frayling. The car which was raced for the first time in mid-1963 at Silverstone by Tony Maggs and two weeks later in the Nürburgring 1000 Km race (the writer was there) by Tony and the late Bob Olthoff, was basically what Ford had in mind. History will tell us that Broadley entered into a deal with Ford and sold them his two MK6s, which were to become the forerunner to the GT40. Due to a clash of wills, mainly with regard to Broadley wanting to build a monocoque out of aluminium and Ford insisting on steel, there was parting of ways and Broadley went on to develop the Lola T70 just down the road from Ford Advanced Vehicles in Slough. Naturally Chapman had hoped that Ford would choose his Hickman styled car but when he lost the contract he suggested that they build the car anyway. The mid-engined car, as can be seen in the photo, is clearly the forerunner of the Europa, the design of which was fine tuned by the ever present John Frayling.

Ron then played a major role in having rules for the smaller car manufacturers simplified by forthcoming U.S. Federal regulations, in particular those pertaining to open cars. As his job at Lotus had by then become largely administrative he resigned in 1967 to set up his own freelance design company. It was a bold move particularly as Ford had asked Ron to return to head up the development of the Capri. As Ron had virtual free rein at Lotus he didn’t cherish the thought of returning to a large organization and commuting on a regular basis to Ford of Germany.

Breakthrough waiting in the wings

Unbeknownst to Ron a breakthrough was waiting in the wings. In 1961, he and Helen had started furnishing their house in Nazeing, Essex and had bought some Swedish whitewood chairs. He used one on which to saw a sheet of plywood and to his dismay cut into their expensive new purchase. The next day he made up a steel framed wooden bench with a huge vice so that a piece of timber could be held in a fixed position and in so doing laid the foundation for what was to become the Black & Decker Workmate.

Finally, when satisfied with his design, Ron hawked it around and called on eight British workshop equipment and tool manufacturers who all rejected it in turn. Stanley Works (Great Britain) Ltd of Sheffield wrote as follows: “Our investigations in Europe produced a very luke-warm reaction. In general, it was felt that the potential could be measured in dozens rather than hundreds.” The letter was appropriately dated April 1, 1968, and as Ron says that decision by the Stanley management was the engineering equivalent of refusing to sign up the Beatles!

Ron battled on by selling his workbench by mail order and at exhibitions for the next four years. Only then did Black & Decker sign up for the European rights and yet later their American parent company turned it down twice.

To date about 70 million Workmates have been sold worldwide and it’s no secret that Ron Hickman has made a great deal of money from his invention. Paradoxically, he’s often had to defend his patent rights from the very people who turned it down in the first place.

In 1977, the Hickmans moved to Jersey in the Channel Islands and Ron spent three years building their magnificent mansion. Although he did a great deal of the design work and scale model building work himself, he eventually commissioned an architect to turn his concept into reality. Named Villa Devereux, it enjoys a breathtaking view over St Brelade’s Bay. Three storeys high, and covering some 1,886m2, set on four acres of land, it’s now a local landmark and in 1987 featured on a Jersey postage stamp.

Ron owned an Elan and an Elite (naturally!) as well as a huge emerald green and silver 1931 Cadillac V-16 tourer that once belonged to the Maharaja of Tikari.

In 1994, Ron was awarded an OBE for “Services for Industrial Innovation”, the first time this citation had been used. So off it was to Buckingham Palace in top hat and tails! Not bad for a Banana boy (a nick name for people from Natal) who went north in 1954 with £100 borrowed from his dad.