After years of research, Ed McDonough reveals the influences and pressures that drove Mexican racing hero Pedro Rodriguez to the pinnacle of motorsport…and an untimely death.

July 11 marks 31 years since Pedro Rodriguez took part in what a number of writers subsequently called a “meaningless Interseries race” at the Norisring in Germany. I have always taken exception to that view, as Pedro loved his racing passionately and found it impossible to sit around when there was a race on and he could be driving in it. However, he wasn’t drawn to the Norisring only by a desire to drive. Quite frankly, he needed the money, and this was something many of even his closest associates didn’t know. Tim Parnell, who was running the BRM Grand Prix team for whom Pedro was driving for the 4th year, more or less knew, and he resisted Pedro’s insistence to go off and do this race. Parnell was one of the very few who were close to the Mexican; in fact, Pedro was Parnell’s son Michael’s god-father. John Wyer, who managed the Gulf Porsche team, and was Pedro’s other employer, also resisted. But like Parnell, found it difficult to stop Pedro when he wanted something even though both could have used their contracts with the driver to stop him taking part. John Wyer always lamented afterwards, “I wished the hell I had.”

Tim Parnell said Herbie Muller’s team kept telephoning the BRM offices in Bourn to speak to Pedro, offering him a considerable amount of money to drive Muller’s spare Ferrari 512M (chassis 1008). The number seemed to start at about $5,000 and went up. Pedro implored Parnell, “ But Tim, they are offering me so much money, how can I refuse?” Parnell recalls how worried he was when Pedro went off to drive “that heap of rubbish.”

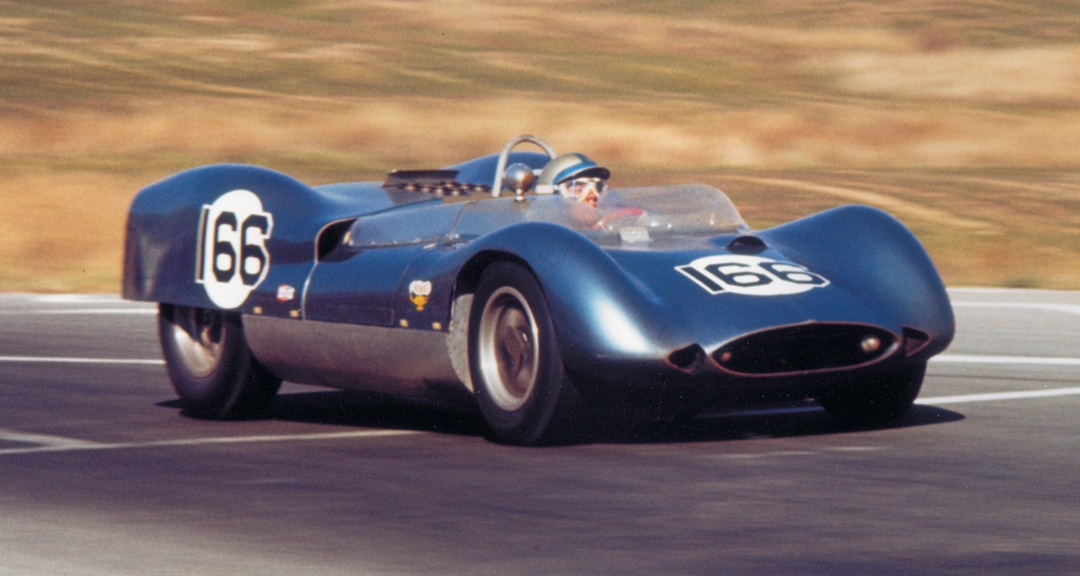

Photo: Elmer Forythe

Pedro, at this later point in his career, was largely moved by a need for money, which comes as a surprise to many. But he was, over the long term, motivated by a fatalistic approach to life. This wasn’t the superficially fatalistic view that many drivers express to the outside world, but don’t really believe. No, Pedro’s view was the result of the influence of both his deeply controlling Mexican Catholicism and a longer standing Mexican attitude, which emanated from the heritage of the Aztecs. Mexicans were long used to having to accept the hard things in life. For hundreds of years they lived in the aftermath of the Spanish conquest of their country. For many, this evolved into a kind of double standard attitude of cautiousness and abandon at the same time – of being profoundly religious on one level, and living a life of, let’s say, “moral relaxation” on another. Support for this idea can be found in the many pictures of Pedro and Ricardo kneeling in prayer in front of their mother in a paddock before a race, and equally, photos of them at night clubs with women who were clearly not their wives! Oftentimes, while the brother’s wives Sarita and Angelina went home, Ricardo and Pedro went out. According to many of the brothers’ friends that I spoke with in Mexico City, it was who they were. They called it “macho Mexicano” and for them, there was no contradiction in this.

By the time Pedro set off for the Norisring that day in 1971, he was keen to race as much as he could. He was earning well and wanted to seize every opportunity to do so. As he was driven to the Paris airport from his apartment by Jean Behra’s son, Jean-Paul, to fly to Germany, he remarked that he hoped to be bringing back “a bag of money.”

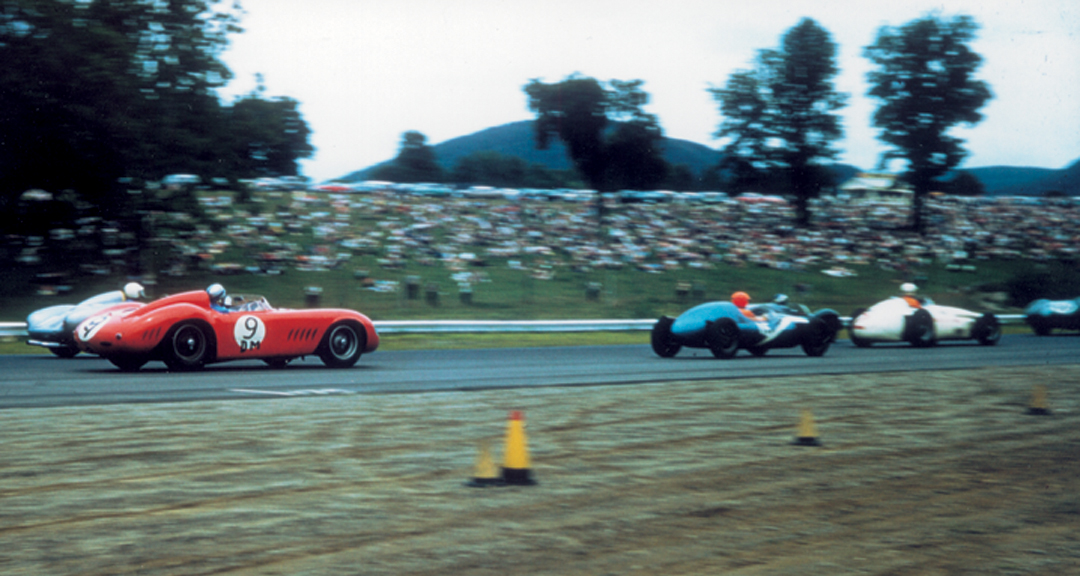

Photo: Allen Kuhn

Of course, the public and international picture of the Rodriguez family was painted in quite a different way. They were portrayed from the very early days as fabulously wealthy, and in relative terms (and especially in Mexican terms) they were. The implication was of family money, and that was true, except it was money earned by father Don Pedro solely to finance his sons’ racing. Don Pedro, at the time and in retrospect, was something of a mysterious character. He was simultaneously described as a “politician,” “gangster,” “sportsman” and “industrialist.” In some ways, all of these were true. He was even said to have owned and managed many brothels in Mexico, although this was probably untrue. He owned the land on which some brothels stood, and he may have frequented them, as he always offered this little sidelight to visiting Grand Prix drivers in town for the big race. But the Catholic Church in Boston owned similar property in the 1960s and I wouldn’t accuse them of “being in the business!”

Don Pedro had worked his way up from literally nothing, and when the boys were born in 1940 and 1942, he already had had a minor career as a motorcycle stuntman behind him, as well as having trained and led the Mexico City police motorcycle riding team. The later gave him the chance to rub shoulders with influential people in business and politics, and he turned this interest into a lucrative endeavor, building a business making barrels, especially for Pemex, the Mexican national oil company. He then used the business to make “bigger” friends, and those friends to create bigger business. He was soon a friend of Lopez Mateos, the man who would go on to become Mexican president. In fact, throughout the Rodriguezes’ racing careers, they had great and public support from Mateos, which helped turn the adventurous twosome into Mexican heroes.

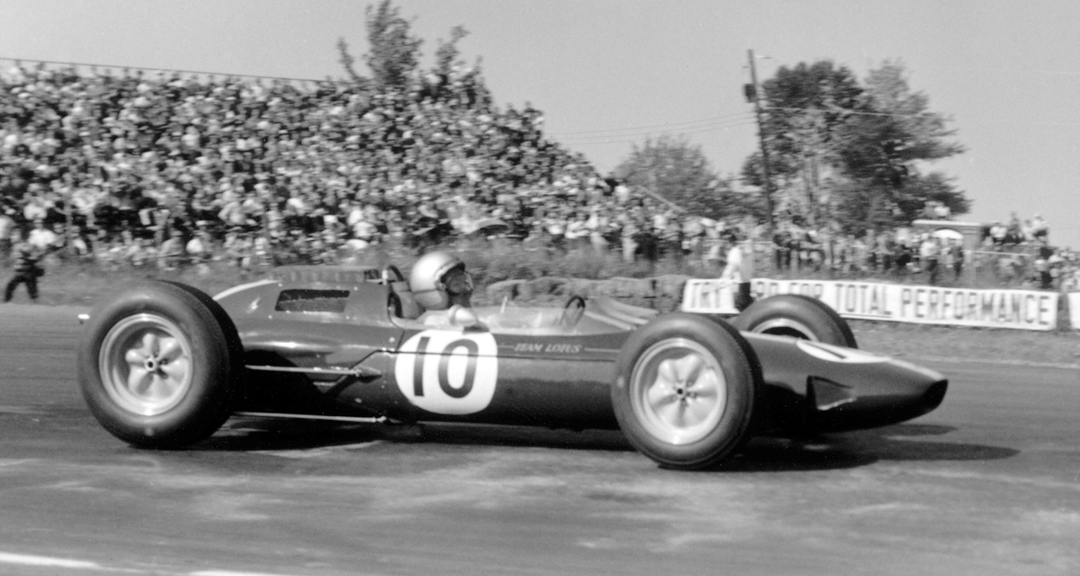

Photo: Nigel Snowdon

They both started, like their father, with successful stints in bicycle and motorcycle racing – becoming national champions at an early age. The first car race came on February 6, 1955, when Pedro was 15 and Ricardo a week short of his 13th birthday – 13…just think of it! The family funds had purchased a Fiat Topolino for Ricardo and an XK120 Jaguar FHC for Pedro; and at the dusty Puebla circuit, they each won their class in production car races. Their karting experience had also helped them and they had extremely good car control from the start. Subsequently, a number of cars passed through their hands in 1956 and 1957, racing at such Mexican venues as Guadeloupe, Vera Cruz, Avandaro, Torreon and Guadalahara in Opels, an OSCA and a Corvette.

Pedro did a number of races in the Corvette while Ricardo graduated to a Porsche 550, frightening the life out of Porsche expert Ken Miles to whom Ricardo finished a challenging second. It was at one of these early races that Don Pedro was heard to say that he was “prepared to accept the sacrifice of one of his sons for a World Championship.” The witnesses to this statement were shocked at the coolness of his intentions, especially in days when racing was thought to be a gentlemanly activity. But indeed, the father wanted to succeed through the achievements of his sons, and was prepared to pay for it, whatever the cost. This fatalistic attitude was deeply ingrained, especially in Pedro, from very early days.

It wasn’t long before the boys burst onto the international scene, at Riverside in September 1957 to be exact, when Ricardo showed the back end of his Porsche to Miles and the rest. The overseas drivers discovered them at Nassau, with Ricardo in the Porsche and Pedro now in a 2-liter Ferrari 500TR. In 1958, they hoped to team up at Le Mans and had a NART-run 250TR Ferrari (chassis 0600), but the organizers refused to allow Ricardo to race because of his age. Pedro teamed up with Jose Behra, the brother of F1 star Jean, and though they retired, the same pairing was 2nd in class at the Reims 12-Hours a few weeks later. The brothers gained considerable experience in 1958 and 1959 in Ferraris, OSCAs, and Porsches at Sebring, Nassau and at many Mexican races. Don Pedro had organized a strong contract with Luigi Chinetti at the North American Racing Team for the brothers to have rapid Ferraris in more important races.

Photo: Lionel Birnbom

Often driving together, the duo was gaining a reputation for fast though sometimes erratic and ill-paced driving. Carroll Shelby recalled how he pleaded with Luigi Chinetti to be more cautious with the inexperienced brothers, but he claims it fell on deaf ears. Subsequently, a number of impressive, though not major wins, came their way, but it was at Le Mans in 1960 when the brothers made their mark on the European stage. Pedro had been sharing with Ludovico Scarfiotti in the TRI/60 (chassis 0782) when it retired after Pedro had set a blistering pace.

I had my first face-to-face encounter with Pedro in July 1959, at Lime Rock, Connecticut, where he was driving in a Maserati 300S in a rather odd International Libre race. This was the same race that saw Rodger Ward gain further fame by out-driving a field of more sophisticated single-seaters and sports racing machinery in an Offy-powered midget! Pedro finished 3rd in that race, but spent most of the weekend languishing in the shade. Though he was very friendly, he spoke very little English and was content to spend much of the time by himself.

Photo: Ferret Fotographic

My second meeting with Pedro, and the only time I ever saw Ricardo race, was a year later at the unlikely venue of Roosevelt Raceway in New York. The brothers had come to the converted parking lot to take part in a revival of the famed Vanderbilt Cup races, this time being run for Formula Juniors. In the race, Pedro finished 5th, driving a Scorpion (which he drove far better than the car deserved!), while Ricardo retired with mechanical troubles. After the race, I had my photo taken with the two laughing and joking brothers, and we shared a Coke together behind the grandstand, laughing at a race with “leeetle cars and beeiig Indy drivers.”

Things moved rapidly for the brothers after that. Pedro and Ricardo did a huge number of sports car events, and in early September 1961, Ricardo was “invited” to try out for the Ferrari Grand Prix team, courtesy of a deal organized by Chinetti and Papa Rodriguez. Pedro could have been there, too, but he was less confident and felt he needed more experience, not to mention that he also wanted to look after business interests at home. At the 1961 Italian Grand Prix, Ricardo was in an F1 Ferrari 156 Sharknose on the preceding Wednesday for the first time and was 2nd on the grid by Saturday!

Ricardo’s F1 career didn’t seem to have any apparent impact on Pedro. They continued to drive together, winning the Montlhéry 1000 Kilometers in October 1961, in a Ferrari 250 SWB (chassis 3005). The pair also shared the Ferrari SP rear-engine sports cars that year, often leading and then retiring. Montlhéry in October 1962 would see them win again in a GTO (chassis 3987) but this was their last race together. Two weeks later Ricardo was killed trying to out-qualify John Surtees in the first Mexican Grand Prix.

The story is often told that Pedro took Ricardo’s death very badly and contemplated retiring, or at the very least taking a long break. The more accurate story is that he wasn’t clear where his career was going. However, within three months he had returned to form, easily winning the 1963 Daytona 3-Hours in a NART Ferrari GTO (chassis 4219). He then went on to race at Sebring in the 3-Hour Race in a Sprite and in the 12-Hours was 3rd with Graham Hill in a 330TRi (chassis 0808). He drove in 14 more major sports car events in 1963, and while he was spending some time looking after a Mexico City car dealership, he hardly seemed to be having second thoughts about being a professional driver. He shared a Ferrari TR 330 with Roger Penske at Le Mans, drove a Genie the first of several times in USRRC events, started dominating the “big banger” sports car races at Bridgehampton, and in October made his Grand Prix debut for Lotus in a third works car at Watkins Glen. I am pleased to have been there to witness his debut, even though he retired.

I was staying just down the hall from Pedro in the motel at Watkins Glen, and though I didn’t hear it myself, Jack Brabham asked what the “carrying on in the Mexican’s room’was!” The next morning, I said to Pedro I would like to follow him up to the circuit to get into the paddock. He set off in his black Ferrari 250GT, and my wife, Nancy, and I followed in our new SAAB 93! Barely able to keep him in sight, even in traffic, he made sure I got through the gates with him, and asked if that had been “fun?” I think Nancy, like so many other women, fell for him then and there. For me, it was enough contact to ensure a chat with him at the races for the next several years.

Unfortunately, Pedro’s Formula One career didn’t take off. He had occasional Lotus drives, which didn’t achieve much, except that the mechanics loved him. When he won the Reims 12-Hours with Jean Guichet in 1965, his sports car career was well established and he was recognized as being very talented, though perhaps not outwardly committed to being a professional. His ability as a wet weather driver was also spotted by serious followers of the sport.

He was reticent, often shy and very few people could claim to have gotten to know him. In late 1965, he drove for Ferrari at the U.S. Grand Prix where he was 5th and came 7th in the Mexican GP. This didn’t turn into anything serious and he was back in a Lotus for some F1 races in 1966. But he was also in Texas driving a Mini-Cooper at the Green Valley Six Hour Enduro, as well as a Shelby Mustang. He had also made three attempts to qualify rather slow cars at Indy, starting in 1963, but like Rindt and Amon, couldn’t come to grips with the place. He also developed a strong view that Mexicans weren’t welcome in Gasoline Alley. On top of it all, Rodriguez also demonstrated great speed in that most dangerous form of racing, mid-1960s Formula 2, where he showed well in a Lotus 44, Protos and a Matra MS5.

Then at the end of 1966, John Cooper and Roy Salvadori asked Pedro if he would like to drive in the Cooper Grand Prix team, starting with the South African race on January 2, 1967. It was an odd race where the fancied runners started to drop out, and local driver John Love looked set to stand the F1 world on its ear by winning, when he was forced to dash into the pits for some fuel. Pedro had moved the cumbersome-looking Cooper-Maserati T-81 up the field and was now in front. Pushing for all he could in the fragile car, he held on for a sensational victory. He drove the uncompetitive Cooper very well the rest of the season, with some good placings, but there were no more wins left in the Cooper team. Roy Salvadori, however, thought Pedro was a great, positive team member, and found him much easier to get on with than the rather demanding Jochen Rindt. Again, the mechanics thought he was great, as they would at BRM.

Salvadori said, “All this stuff about Pedro being hard on cars was nonsense. He didn’t have the greatest technical ability, but he could get the most out of a car. He never questioned what he was asked to do. He just went out and drove, and I also found him very sympathetic, unlike Rindt. When Pedro went to BRM, we were sad to see him go, and John Cooper was upset because he broke his contract, but we understood why he went.”

Almost by accident, Pedro was invited by John Wyer to drive one of the Gulf Ford GT40s at Le Mans in 1968, with Lucien Bianchi. In alternating wet and dry, the pair worked their way into the lead. I was down at Mulsanne corner, signalling for the Mike Salmon Ford GT40. In the night, Pedro would sail down the straight and was the only driver to consistently slide through the slow corner with no waggle of the tail. He was utterly smooth. He won.

Pedro did more and more F2, even though he had been injured in a very big crash in the Protos at Enna (VRJ Nov. 2001). Aside from his fatal crash, this was the only time in his career he had injured himself. He stayed with BRM from 1968 on, being “down-graded” to the “second” team in 1969 by Louis Stanley. Rodriguez returned to BRM in 1970, where he helped launch a BRM resurgence. It was at this point that he was reaching his peak as a Grand Prix driver and a sensational high-speed victory at Spa came his way as a result. It was at this same time that he also started his career in the Gulf-Porsche team, and the last two years of his life were filled with wonderful races. One of the most memorable of these was at the Brands Hatch 1000 Kms. in 1970 where it rained non-stop. Pedro overtook under the yellow, which he didn’t see, and was brought in, lost two laps and dropped to last place. However, in the most amazing demonstration of car control, he not only regained the lost laps, but made them up again when his co-driver took over and went slower. No one who saw that race ever saw a better wet weather driver. John Wyer commented, “I don’t think he knows it’s raining, so don’t tell him!” Pedro was always stunningly quick in the 917, wet or dry.

Tragically, Pedro’s racing potential would never be fully realized. Rodriguez was leading at the Norisring, in the Ferrari, when something went terribly wrong, and he crashed, thus closing the book on the final chapter of the talented young racing “Matadors” from Mexico City.

As I look back now, I think that Pedro’s talent and spirit are perhaps best summed up in a tale, which Pedro told at his own expense, and was passed on to me by journalist and fellow Pedro admirer Eoin Young. At the Tasman championship races in 1968, Pedro came in after the end of the Longford race and the mechanics asked him how he had “gotten on with the 6-speed gearbox.” Astonished, he proclaimed in a loud voice, “Eeeet has Seeeix gears!?!?!” It wasn’t that he hadn’t used sixth…he just never found first. Even with this handicap, he finished 2nd on the day.