1955 Zephyr Special

Today, you would describe Eldred De Bracton Norman as a lateral thinker, but during the 1950s, “eccentric” in the kindest possible way would more easily come to mind. Now, over a half a century later, just to mention his name brings knowing looks and the slight nodding of heads as those who know of his work reflect on how amazingly advanced it was. The less kind amongst us would probably think the word “bizarre” might be more appropriate. Whatever Eldred Norman was, his work was certainly noticed.

Just looking at the map of the world will show you that we, in Australia, are a long way from the rest but, to be truthful, we like to think that the rest of the world is a long way from us. We like it that way as it keeps the less-desirable happenings of the world on our TV screens and not on our streets. Many have used the term “tyranny of distance” when it comes to describing what it’s all about and it applies especially to competition vehicles.

We all know that racing cars are just downright bloody expensive and to put the cost of freight from the other side of the world on top of it makes paying for whatever we want all that more painful. Plus, there is a little thing called His (or Her) Majesty’s Customs and Excise, meaning that, for every competition car imported, there is a little man (or woman) standing there with his (or her) hand out wanting their cut by the way of import duty. If it wasn’t paid, how else would the government be able to afford the wages of those people who are there holding their hands out? If you are now thinking that this is going around in circles, you’re dead right.

So, expensive cars and the inherent dislike of Australians to pay taxes, no matter what they were called, left the enthusiast with the decision to either sit back and watch others enjoy their racing or build their own cars. So was born what we now see as the golden period of the Australian Special. While many an enthusiast took the path of modifying a road car, others built their own chassis and clothed them in purpose-built bodies like the Crowfoot Holden (VR, July 2006). However, there were a few enthusiasts who built some amazingly innovative cars that made you think that they must have done a little crystal-ball-gazing into the future. One such car is the Zephyr Special built by Eldred Norman in the first few months of 1955.

Those with a few more shekels in their pockets who didn’t mind sharing them with HM Customs and Excise did bring cars in from overseas, such as the Alta of Tony Gaze, Lex Davison’s 2-liter Alfa Romeo, and the Coopers of John Crouch and Keith Martin.

Outrageous Larrikin

Sadly, Eldred Norman is no longer with us, but we did speak to his son Bill who has caught some of his father’s interest in racing cars and currently runs a self-made hillclimb car, as well as a Reynard 92D Holden V6 F4000. Bill describes his father as a non-conformist and an outrageous larrikin. That’s a marvelous, almost endearing word, that is used in Australia to describe someone who thumbs his nose at rules, regulations, and social norms. However, to Bill, his father was also just “Dad” who would disappear into the workshop and seem to never come out. Bill is one of three siblings and their mother was Nancy Cato, a well-known Australian writer.

The end of WWII saw Eldred Norman living in Adelaide, South Australia. Interested in motor racing, Eldred had heard that when U.S. forces had returned home from New Guinea, they had left many vehicles and other equipment that would have been just too expensive to take home to scrap. Bill can recall his father saying that parts of New Guinea were littered with D7-style tractors, Jeep weapon carriers and the like.

So Eldred Norman traveled north to New Guinea, the result of which was the first of the Norman Australian racing specials. Called the Double V-8, its chassis came from a Dodge weapon carrier and its aluminum body had previously seen service as aircraft bodywork. The engines were two Ford side-valve V-8s mounted line-astern with twin-row industrial sprockets in place of the flywheel of the front engine and the other mounted to the front of the rear engine’s crankshaft. Joining the sprockets was a large four-row drivechain. With two engines, there were also two radiators, with one mounted up front and the other at the rear behind the driver. Suspension on the Double V-8 was independent all around and Norman must have known that he would have problems with fading brakes, as he designed a brake-water cooling system using an electric fuel pump at each wheel.

The car was finished back in Australia and was actually registered to drive on the road in Adelaide. Bill Norman recalls that his father tested his cars on the road and would frequently be seen driving through the Adelaide hills with number plates tied with string around his neck. Eldred Norman built the Double V-8 to race and started in the 1950 Australian Grand Prix held at Nuriootpa, just 50 miles north of Adelaide. However, success eluded him, as he only lasted two of the 34 laps of the 4.37-mile square-shaped circuit, but he will forever be remembered for the almost-impenetrable clouds of steam given off every time he applied the brakes.

He fronted up again for the 1951 AGP at an around-the-houses circuit in the town of Narrogin south of Perth, Western Australia, some 2,000 miles away on the other side of the country. When first built, the Double V-8 weighed an amazing 2,500 pounds and needed all of its 7.8-liters to make it competitive. For the race, Norman had dramatically remodeled the bodywork, reducing the weight and, for a time, actually led the AGP until forced to retire with front suspension problems.

Maserati Interlude

Following the 1951 AGP, Eldred Norman wanted to move ahead and sold the Double V-8 to Western Australian Sydney Anderson, who continued to compete in the car.

Also competing in the 1951 AGP was Scotsman Colin Murray in his Maserati 6C who, in addition to driving, imported racecars and sold them off to local drivers. Bill Norman recalls vividly his father buying the 6C and, thereby, sowing the seeds of a lifelong contempt for small capacity engines with multiple camshafts. Bill recalls the supercharged Maserati as being very noisy but also having an insatiable appetite for pistons. Bill also recalls many hours as a child when his small hands were put to good use tightening the Maserati’s many inaccessible nuts and bolts—one-sixth of a turn at a time!

Highly dissatisfied with the Maserati, Norman at Christmas, 1953, took delivery of a very early Triumph TR2 and immediately commenced to prepare it for competition. The original steel wheels were replaced by a set of wires and he fitted an overdrive, a 30-imp-gallon fuel tank as well as a water tank and oil reservoir. Engine internals were also modified and strengthened to handle supercharging and methanol-based fuels. For a time, he experimented with fuel injection of his own design but eventually returned to a 2-inch SU carburetor. The GM 271 Roots blower was driven at 1.1-time engine speed for 12-psi boost, though even with four V-belts, there was still slippage.

It was with the TR2 that Eldred Norman was to achieve his greatest racing success in the 1954 Australian Grand Prix. He had entered the TR in supporting races knowing that success would lead to an invitation to compete in the AGP. Bill Norman tells the story that his father and mechanic Mac Wilton set off from Adelaide driving the TR towing a trailer loaded with two 44-imp-gallon drums of methanol-based fuel to Southport in Queensland: a one-way distance of over 1,250 miles on what would have been mainly unpaved roads.

The event was to prove successful for Norman as not only did he win two supporting races, but he also finished an astonishing 4th outright in the 1954 AGP. After the race, the pair retraced their steps by then driving back to Adelaide!

Like so many innovative people, as soon as he perfected the TR, Norman completely lost interest in it and sold it off. His next car, the one that we are featuring in this month’s VR, was built early in 1955. Bill Norman believes that his father must have been inspired by his own ideas for the new car as it was built in just the first 10 weeks of the year. It was a time when “Dad” would disappear for what seemed like days into the workshop.

Without a doubt the car that resulted from those 10 weeks was the culmination of all of Eldred Norman’s innovative thinking and would initially prove to give race scrutineers the horrors—to many it became known as the “Diabolical Device.”

The Zephyr Special

It may have been diabolical, but everyone who sets eyes on the Zephyr Special today says that it was very clever indeed. I can recall the first time I saw the car, about four years back. It was a salute to the Australian Special and, while it wasn’t racing, it was on display with many others under a large marquee.

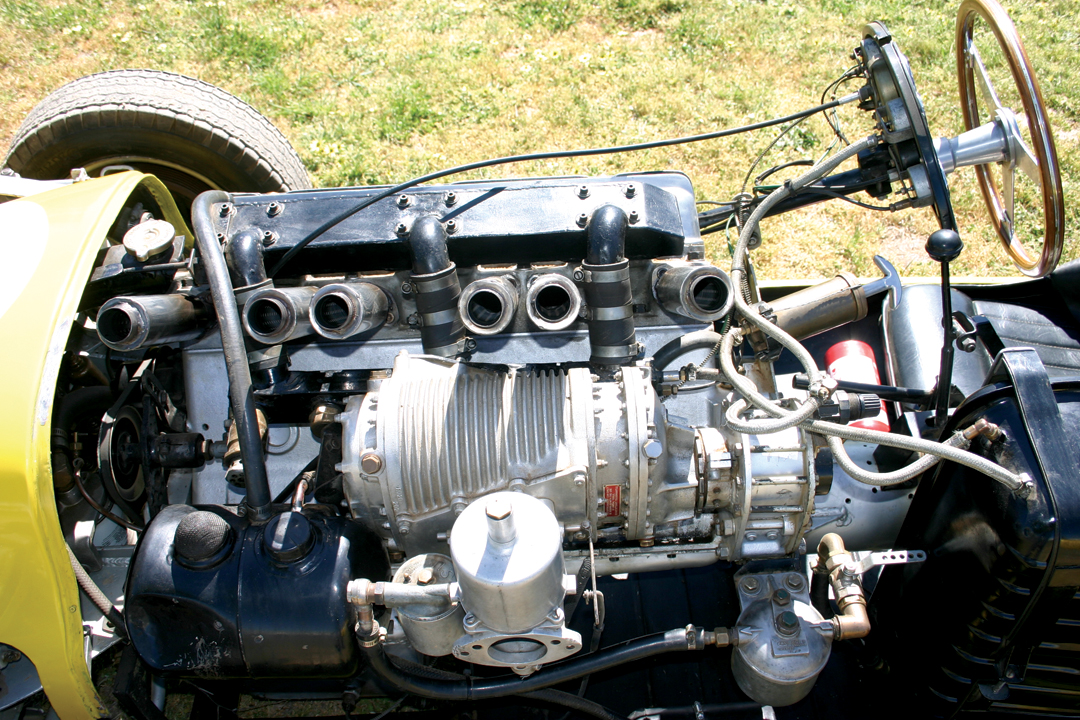

On first glance, it’s a very unassuming-looking motor car, as its cigar-shaped body gives no indication as to what lies beneath. Although I can remember being interested in the six short stub exhaust pipes pointing skywards through the bonnet. That was the first time when it had its body on and, when I went back a hour or so later, the top half of the body had been removed. The engine looked vaguely familiar and it took me a couple of seconds to draw a connection between Zephyr Special and Ford Zephyr to understand its origins. The English Ford Zephyr was a very popular car in Australia during the 1950s and early 1960s and was Ford’s mainstay, until the introduction of the Ford Falcon.

I can remember thinking about the chassis, as I couldn’t see one. I looked closer and all I could see was a bloody big tube that was connected to the back of the engine and disappeared down toward the rear of the car. Interested wasn’t the right word to describe how I felt—enthralled was more appropriate. I introduced myself to Graeme Snape, the owner, and exchanged details. However, before being able to delve into the complexities of the car I was waylaid and it was to be another four years until I had that chance to discuss the car with Graeme, but more of that later.

Inspired

Looking back, those first 10 weeks in 1955 for Eldred Norman, I suspect that “inspired” would have been a good word to describe how he felt. The 1955 Australian Grand Prix was scheduled for Port Wakefield about 40 miles north of Adelaide and not far from where the Normans were living.

Bill Norman can vividly recall his father being extremely busy during the time and only coming inside to eat and catch some sleep. Bill said the result was the first racing car in the world to actually use the engine as part of the chassis. While some may argue the point, it was certainly years before Lotus did anything similar.

Up front was a modified Holden suspension bolted directly to the front of the supercharged Zephyr engine, while at the rear was the tube that carried through to the back of the car and the rear-mounted clutch and transaxle gearbox from a German Tempo Matador light truck. The fabricated rear suspension was connected directly to the gearbox. In direct contrast to Norman’s severely overweight Double V-8, the Zephyr Special weighed in at a svelte 1,527-pounds. Initially, the car was christened the Eclipse Zephyr, after Adelaide motor trader Eclipse Motors, who gave Norman the engine.

Bill remembers his father finishing the car and taking it to have the body built in Adelaide. He was with his mother in the family Ford Zephyr convertible while his father drove the bodiless Zephyr Special. While the necessary trade plates were connected to the car, Bill doesn’t think they would have helped if they had come across a less-than-friendly member of the police.

Grand Prix

It would be a fairytale beginning to say that Eldred Norman met with success in the 1955 AGP, but he was up against some formidable opponents. These included the Maserati A6GCM of Reg Hunt, Doug Whiteford’s Talbot Lago and an unusual Bristol-powered car that had its engine in the back. Of course, the 1955 AGP will be best remembered by the first appearance of Jack Brabham in the Cooper Bobtail, which he eventually drove to victory. Eldred Norman finished in 8th place having completed 74 laps of the 80-lap event.

Norman continued to compete in the car to the end of the following year, when through a combination of waning interest and a severe lack of money, the car was sold to Keith Rilstone. Bill Norman puts it down to advertising being banned from competition cars, but while the Zephyr Special generated quite a bit of newspaper coverage, not much of it put money in the bank.

Norman then changed direction completely and focused his life on inventing and, in particular, devoted his energies toward astronomy. While he did not construct any further competition cars, he did design a supercharger which dramatically improved the performance of Holden cars. He also wrote a book on forced induction called Supercharge which is still available today.

During this time, he also saw a market in selling large capacity telescopes, so he designed and built his own astronomical dome and telescope, complete with opening roof and driven gears to compensate for the earth’s rotation. However, he found that he couldn’t obtain lenses big enough to suit. So, in typical Eldred Norman style, he designed a machine that would grind the lens to within tolerances of 3 millionths of an inch.

The Normans moved to the warmer climes of Queensland in 1967, but sadly Eldred died from cancer in 1971.

Zephyr Meeting

We arrived at Wakefield Park some two hours south of Sydney to see Graeme Snape taking the Zephyr Special out onto the circuit. It was actually the first time I had heard the car, let alone seen it run. It makes a great sound even just on idle and especially when driven with any enthusiasm. The event was the bi-monthly GEAR meeting—that stands for Golden Era Auto Racing. GEAR is a group of enthusiasts who get together every two months to run their cars at Wakefield Park in a noncompetitive way. Sure, like cars are out on the circuit at the same time and passing is allowed, but it’s a race against the clock and silly business is decidedly frowned upon.

We were standing next to Greg and Matthew Snape, sons of Graeme and Robyn, when all of a sudden the Zephyr Special streaked past, down the straight heading for the first right-hander. Robyn is helping out in the control tower as both she and Graeme are on GEAR’s organizing committee. All of a sudden Greg and Matthew let out a great cheer as their father and the Zephyr Special disappear off the circuit in a great cloud of dust. Greg remarks at how twitchy the car is.

I have been involved with historic racing since the early 1970s and I can recall the name of Graeme Snape for all that time.

“It’s something we have always done together as a family,” Graeme remarked. “My mate Robbie Rowe got me involved and we bought the motorcycle-engined BB Aerial which was followed by a 1956 Cooper MkX that came to Australia brand new and was fitted with a BMW motorcycle engine. We bought the Zephyr in 1983 and ran that and the Cooper all over the place. Once I got the Zephyr, Greg took over the Cooper and we used to go everywhere. We’ve been to West Australia with both the cars and to New Zealand, but I ended up taking the Cooper over there as the Zephyr was broken. If there was a historic race, we were there—almost a way of life.”

Robyn Bought It

“It was Robyn who actually bought the Zephyr Special,” Graeme said. “That was from Peter de Mack in Adelaide. The first time I saw it and fell in love with it was when I was running the Cooper at Adelaide and the previous owner to Peter, Ken Messenger, had it going pretty well. The Cooper is a good little car but I thought I was going all right flying down the straight, then Ken came by me so fast I thought I was in neutral. It was there and then I thought to myself that I would love to own that car.”

“When Peter de Mack ended up getting it, I asked him for first refusal. He said yes but added that the South Australians would never let him sell it out of the state. I said that Robyn and I were virtually honorary South Australians, as we spend so much time there. He ended up wanting to sell it but had to get permission from the South Australian Historic Racing blokes to sell it out of the state. It wasn’t a problem when he said I was buying it, as they knew that I would always bring it back.”

“Peter rang up but I wasn’t home so he spoke to Robyn. He told her that he had decided to sell the Zephyr and that I had wanted first option. He said what he wanted for it, which was a bloody lot, almost enough to buy half a house. Robyn said straightaway, without blinking she reckons, ‘We’ll take it!’ She then went straight to the bank manager and organized the loan without me. I’m glad that she did it all because I would have thought and thought about spending so much money on an old racing car that we probably would have lost it!”

Completely Rebuilt

“Peter had completely rebuilt the car and had done a magic job,” Graeme added. “It was pretty rugged when he bought it off Ken Messenger, although it was Ken who had gathered up all the original pieces together. It had been split in half as it had been owned by two friends who had a parting of the ways—one to drag racing and the other to dune buggies, and the car went the same way. Ken put it back together and ran it in historic racing although it was very unreliable and Peter bought it from him.”

“The car became very successful in South Australia mainly in Keith Rilstone’s hands who bought it from Eldred Norman. Eldred didn’t have it all that long as he was happy at creating but really didn’t sort out the car. In 1956, Keith Rilstone fitted it with a 2.5-liter Mk2 Zephyr engine with a Raymond Mays head that he got from Charlie Dean at Repco. He also made changes to the front suspension, put an antiroll bar on it and lowered the top wishbone pivot point, thus lowering the roll center of the car. It gave the car a new lease on life as it had started to become an also-ran. Rilstone ran the car competitively right through to 1965 and had entered the car in the 1961 Australian Grand Prix starting on the third row of the grid amongst a brace of 2.5-liter Climax-engined Coopers. Unfortunately, he retired during the race.”

What’s So Special?

Looking at the car, what makes it so special is clearly obvious, but I was interested to hear from Graeme on what is so different about the Zephyr Special.

“The engine isn’t all that special,” Graeme responded. “Except that it lays over and the exhaust pipes come straight out the top of the bonnet and the big blower sits on the side. It’s at 45-degrees and my feet go down under the slope of the engine. Bolted to the front of the engine, where the timing cover used to go, is a modified FJ Holden front suspension that has been cut and shut. This was years before they used the engine as a stress member, way before Colin Chapman started doing it. He is sort of credited as one of the first blokes to ever do it, but Eldred Norman predated that by quite a few years.”

“Bolted to the back of the engine is a six-inch diameter tube and through that runs the drive shaft to the flywheel and clutch, which are just next to my left hip. Behind that is the modified Tempo Matador truck transaxle, which is sort of like a big Volkswagen box but made by ZF. The rear suspension bolts off the gearbox. Except for the original drop gear, it’s been some time since the gears in the gearbox resembled anything that left ZF. First gear in the Zephyr Special is actually the same ratio as the original third and the box lost its reverse years ago.”

“The chassis is really a six-inch torque tube,” Graeme added. “It doesn’t move as everything else comes off it, like the fuel tank and seat are bolted to brackets welded to the tube. The two-piece body is in light aluminum with an undertray that hangs off a couple of brackets on the tube and the front cross-member. It just sits there and the top drops down over the whole of the car and clips into place.”

“It’s a very unassuming-looking car. Very short too, making it unforgiving and twitchy with all that power. On a good day, it’s putting out somewhere between 280 and 300 bhp, when a standard Ford Zephyr engine would normally put out around 86 bhp.”

Achilles Heel

“It’s quite a reliable car,” Graeme continued. “However, its Achilles heel has always been the transmission, although that was sorted out once we found the right steel to make the input and output shafts. We have also thrown one rod, but that was my own fault by not watching the oil pressure. In Keith Rilstone’s hands, it was very reliable and, in fact, Keith got to the stage where he wouldn’t even wash it, in case he jinxed it!”

“It is also very hard on clutches being very high-geared with 90 mph in first gear, 130 in second and 150-plus in top. It will see close to 160 mph down the straight at Eastern Creek and Phillip Island, pulling 6,300 rpm in top. In a straight line it is a very stable car, but it hates fast, sweeping corners as it’s so short in the wheelbase. Quite often it will catch me out, particularly now as I’m getting older and slower.”

“Not long ago Greg had a lose too going up the back,” Graeme added. “He came back complaining that it was twitchy. The tires on it now would have to be 10 years old, which is probably something of a world record for racing tires. If we were running it seriously we’d put decent rubber on it. It has always run 13-inch wheels, as that’s what the Ford Zephyr used. The centers are from a FJ Holden machined down to take the Zephyr rims.”

“You have to keep it tidy as it’s very unforgiving,” Graeme remarked. “It’s not a car that you can slide, but it’s great on a circuit that has short lengths between corners and a long straight. It was brilliant on the old GP street circuit in Adelaide. We had it there a couple of times for support events to the AGP in the early 1990s and it loved it there. It has tremendous acceleration once you get it off the line, which can be difficult. You either bog down because there aren’t enough revs or you’re going sideways with the back wheels spinning—there’s not much in between!”

“The engine is bored 40-thousandths over, balanced and has good rods from a Toyota twin-cam engine. The original Zephyr rods weren’t all that good, but it has a standard Zephyr crankshaft. I have just freshened the engine and refitted the Mahle pistons that Peter de Mack had had made. It’s not very good in the braking department, as it has very period brakes. They are old Girling drums out of a Vanguard…they keep you awake.”

Beautiful Noise

I remarked that the Zephyr Special makes the most beautiful noise. In response, Graeme said that throughout their ownership the noise has caused problems because they won’t change the car as it’s been making the same noise from when it was built in 1955.

“The noise is part of the car’s history and is well documented,” Graeme remarked. “CAMS (Confederation of Australian Motor Sport) in its wisdom decided ‘thou shall not exceed 95 decibels’ and, since that was brought in, we’ve had to fight tooth and nail to be able to run the car in its original form. Even to the stage of having to go to our local member of parliament to get political help. Eastern Creek has a noise exemption for historic racing from when it first opened in the early ’90s so that we could run the Zephyr. Now the exemption is automatic. To get around that, I would have to fit an exhaust system that would run the length of the car. I was asked to do that but the added complication was that it would have to be detachable so that the top half of the body could be removed.”

“Over the years, because of the hassles we’ve had with the noise of the car, it has started to turn us off running somewhat. It wasn’t until we started GEAR going that there wasn’t a problem. At Eastern Creek, it runs about 116 decibels but, with most things, noise is in the ears of the beholder as enthusiasts in our age group like the noise but at the same time hate loud music!”

Looking after the Zephyr Special

Graeme says that as the top of the body lifts completely off, everything is simple to get at. Removing the gearbox is straightforward to get at the clutch. However, the engine is a little more difficult because if you have to pull it right down, the car has to be pulled to pieces, as it holds the car together. It’s still a wet sump but it’s not the standard oil system, as Eldred Norman found out that one of the weaknesses of the Zephyr system was the low volume of the oil pump. The engine has an agricultural-type gear pump at the end of the camshaft sitting out over the front cross member with hoses running to the sump, oil filter and back into the main oil gallery. Not fitted with an oil cooler, it works the oil hard but as it never had one, Graeme is loathe to fit one. He remembers quite a few times when the oil temperature gauge was way past the maximum. As far as coolant temperature goes, Graeme says that the methanol fuel keeps it running within reasonable limits.

Driving the Zephyr Special

The gearshift is high on the left side, almost chest height. It leads down to a ball joint and an exposed square rod that runs along the top of the tube toward the rear. It’s easy to amuse yourself for a couple of seconds moving the gearstick back and forward.

Wakefield Park is a clockwise circuit of 1.4-miles built on the side of a slope and, as you could imagine, has mostly right-hand turns. However, I have found the most difficult corner in the circuit to be a sharp, double-apex left-hander that also slightly falls away. It’s a corner that has to be taken a little late, unless you end up exiting onto the dirt on the other side, causing a slight embarrassment, especially if it’s not your car!

I fall into the category of people who like aircraft noise and I particularly like the noise of the Zephyr exhaust. First is across to your left and forward, then second is back, across to your right and back again, while top is straight up and forward. The blower spins at 1.5-times engine speed and provides positive boost at 3,000 rpm. Getting into the “crash” first gear does require a little determination, and moving off at racing speeds needs an equally determined right foot along with a wary eye on the centrally mounted tach. The clutch is not what could be called progressive, just all of a sudden, you’re away.

Once away it quickly moves into scalded cat territory with a change into second made easy by the helical, but nonsynchro, gear. There is no time for top by the first right corner; yes, there is a little retardation there from the four wheel drums that were originally built to stop a 1.5-ton Standard Vanguard. Then it’s strong acceleration up the hill taking care not to break traction and into top for a slight left-handed sweeper that has to be taken with a little care. Back to second for a wide apex right-hander that seems to go on forever, until the world’s shortest straight, where top is selected once again for what seems like seconds.

The left-hander arrives all too quickly and so does the memory of the car’s unforgiving nature, so it’s taken with care and no heroics. Graeme later says that when it starts to let go sometimes, you might catch it first off but then suddenly it will swing back going completely the other way and you find yourself looking in the wrong direction. The track continues slightly to the left before sweeping right and a short straight, so it’s a matter of accelerating through second and into top. All too soon it’s an oppositely cambered hard right-hander leading onto the straight. So it’s back to second, although Graeme says first can be used for maximum acceleration down the straight with the start/finish line passing in a blur.

For a 50-plus-year-old car, the Zephyr Special is super quick.

Buying a Zephyr Special

I don’t like your chances with this, although Graeme did say that over the years there have been a few people from overseas interested in the car. However, the car is subject to Australia’s Protection of Movable Cultural Heritage Act, so whoever owns it in the future would have to keep it in Australia. However, remember the Zephyr Special is very much a family car, so read into that what you will. Graeme does have full FIA papers on the car because he and Robyn were going to take it to Goodwood a few years ago but, as they started to do the sums, it just couldn’t be justified. However, Graeme thinks that one day their son Greg may take it there.

So there you have surely one of the most innovative of all Australian-built specials that grew from the fertile mind of an equally innovative Australian. Whenever the Zephyr Special is mentioned to enthusiasts young and old, each and every one of them remark what a wonderful car it is. They’re right of course.

Specifications

Chassis: Six-inch diameter tubular backbone, stressed engine and transmission unit.

Body: Hand beaten Aluminum.

Wheelbase: 6ft 9.8in (2,080mm)

Weight: 1,527lbs. (693kgs)

Suspension: Front: Independent with unequal length wishbones, coil springs, telescopic shock absorbers and antiroll bar. Rear: Independent with single upper transverse leaf spring, lower wishbone and telescopic shock absorbers.

Steering Gear: Worm and sector. (General Motors Holden)

Engine: Six-cylinder, Ford Zephyr. 2,553cc (Standard crank)

Power: 280/300bhp at 6,200 rpm

Fuel System: Wade RO20 Supercharger with a single 2-3/8 SU carburetor.

Clutch: Single dry plate.

Gearbox: Modified Tempo Matador transaxle transmission.

Gears: 3 forward, nil reverse

Foot Brake: 4 wheel drums (twin leading front & leading/trailing rear)

Hand Brake: Mechanical to the rear wheels.

Wheels: 13-inch steel – Holden centers with Ford Zephyr rims

Tires: 5.00 X 13 Hoosier

Resources

Graham Howard, Stewart Wilson, John Blanden, The Official 50-Race History of the Australian Grand Prix, 1986, R&T Publishing, ISBN 0 9588464 0 5

John B. Blanden, Historic Racing Cars in Australia, 1979 & 2004, Turton & Armstrong Proprietary Ltd Publishers, ISBN 0 908031 83 1