1958 BRM P25 Chassis 258

It may come as a surprise to many people that Stirling Moss always regarded the BRM P25 front-engine car as one of the best cars he has ever driven. “Great car–bad team” was basically his view. More about that later, though it was especially interesting for me to have the chance to drive this car in the presence of “Sir Moss” and to be able to chat about “our cars” together!

The opportunity to test one of the great underrated, yet truly significant, Grand Prix cars came at the 2007 Goodwood Festival of Speed, courtesy of the Flack family and James Hanson, with the help of the Hall & Hall team. The car was made available as a suitable vehicle from which to do “in-car radio”… I love the media business! I was sharing the car over the weekend with one Brian Redman, another highlight, all in front of many, many thousands of people and TV cameras. This was all happening in the car that Jo Bonnier took to victory in the 1959 Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort–BRM’s first ever World Championship Grand Prix win.

BRM Breakthrough

Perhaps because the P25 looked like it was finally going to reach its potential from that day on in Holland and didn’t, that the car has been somewhat overlooked over the years. After so many years of trying, BRM finally had won a Grand Prix, and then not much more happened with that car, the front-engine era came to an end, and BRM and everyone else put the engine behind the driver. Well, everyone except Scarab and Ferguson—and we know what happened there.

The P25 was perhaps the end of one generation, as the next had arrived just as it had finally achieved victory. It had all started many years before when Raymond Mays and Peter Berthon of ERA fame had conceived the idea for British Racing Motors and a car which would challenge the world’s best when motor racing returned after the war. What eventually appeared was the amazing-sounding, supercharged, 1.5-liter V-16. The early years, when the car was entered for race after race without appearing, were characterized by a great patriotic following. The V-16 Project 15 car made its race debut at the International Trophy at Silverstone in late August 1950. This was a nonchampionship race but a superb field had entered and huge crowds came to see the BRM break its transmission as the flag fell with Raymond Sommer trickling forward just a few feet. Later, Parnell won a short race at Goodwood, while he and Peter Walker at least achieved a combined total of 35 of a possible 100 laps, in Spain, at the end of the year. But BRM had already become the butt of many jokes.

The cars that were going to beat the Italians finally made it into a championship race, the 1951 British Grand Prix; they only made it onto the back of the grid but did finally finish. They appeared at Monza that year but did not manage to start, and really, that was it. In 1952, the World Championship was run to F2 2-liter rules. The season started in hopes that F1 would continue, but there were not enough competitive cars. When the early races indicated the pattern, the F1 cars including the BRMs became redundant, did some of the seven minor F1 events, and then went on to do Formula Libre. Even Fangio and Gonzales drove them at Albi, but they both retired early. They retired in Ulster and at Boreham. There were only four F1 races in 1953, with Gonzales getting a 2nd at Albi. A BRM did not appear again in an F1 race until September 1955, and that was Peter Collins in the first P25…and even that crashed and didn’t get into the race itself!

Sir Alfred Owen took over the running of BRM, and Tony Vandervell who had been part of the original consortium had left to build his own car, the Vanwall, frustrated by the incompetent corporate approach at BRM. The V-16s were sold off and refurbished and reappear even today at historic races. Graham Hill drove one once and said, “I don’t know what all the fuss was about!”

When the new 2.5-liter formula for Grand Prix races to F1 rules was established for 1954, an engine design was produced by Peter Berthon and Stuart Tresilian, who was an engineering consultant. He tried to sell his design for a 16-valve, 4-cylinder motor to Connaught, but they couldn’t afford it. This was at a time when the BRM board was considering “half a V-16”–a 750-cc supercharged unit–they refused to learn. The decision was then made to proceed with the Berthon/Tresilian plan, but eventually make it a 2-valve-per-cylinder engine rather than the originally planned 4-per-cylinder. These would, however, be somewhat unusual in that the valves would be quite large. Development was slow on the new car and it was clear that it would not be ready until late in 1955. Meanwhile, Peter Collins was driving the later version of the V-16 in Formula Libre races. Then Peter Berthon had a serious road accident, which slowed the program down even further, so Tony Rudd took over.

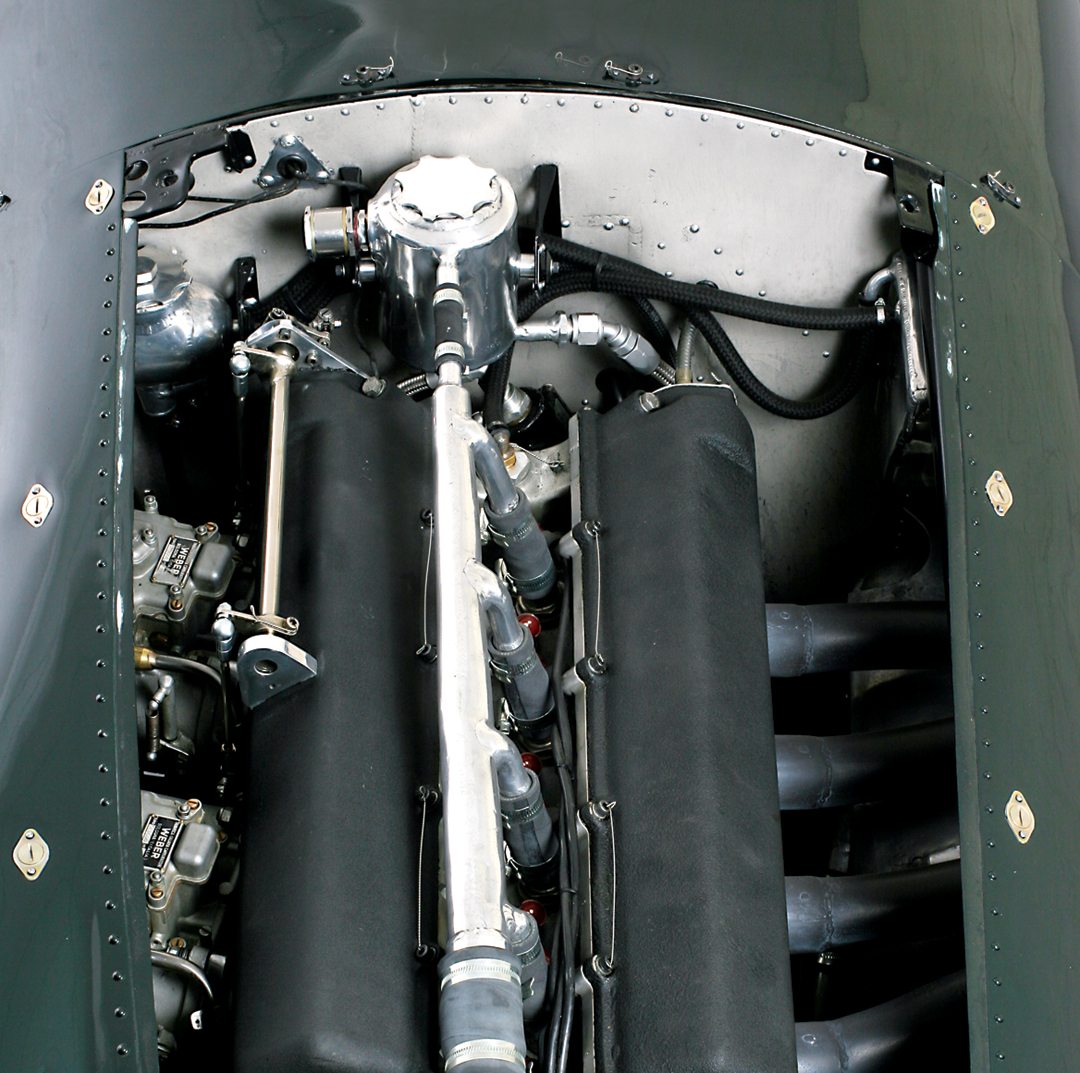

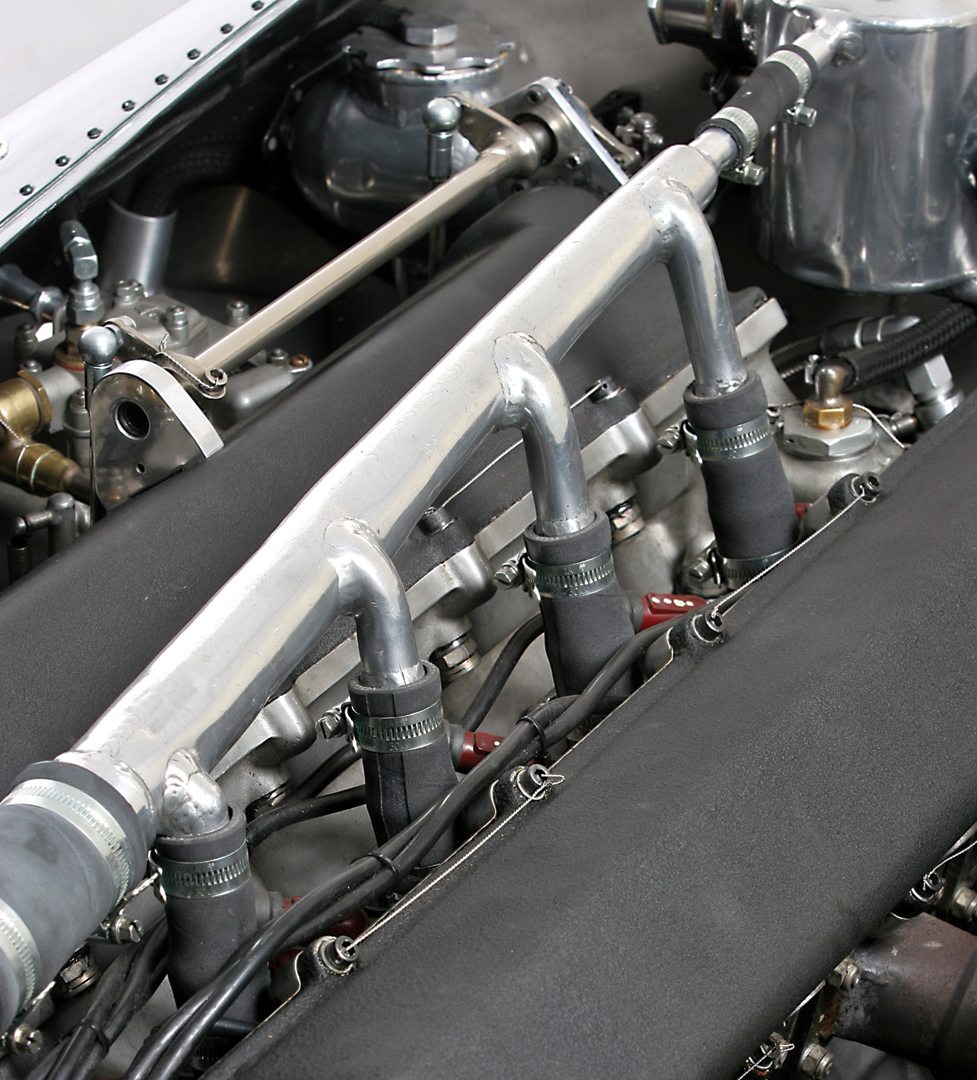

The chassis design was simple but clever. It was a multitubular frame with stressed aluminum panels riveted on, thus forming a semi-monocoque. To keep the car’s weight down, the openings for the cockpit and the engine bay were very small in the first cars, and access was not easy. There were some new ideas incorporated into the P25. Berthon and the late Alec Stokes designed a 5-speed gearbox (with reverse) located behind the rear axle line. Front suspension was by independent wishbones with struts from the larger V-16. The car was quite small and weight distribution was even front to rear. This led to the use of outboard disc brakes–three of them–two front and one rear. Each front brake would take 35% of the braking load and the rear would get 30%. It seemed logical, but logic rarely applies so easily in racing.

Photo: James Hanson/Speedmaster

As the first cars were approaching completion, BRM purchased a Maserati 250F to keep their hand in current F1 racing. Imagine McLaren running a Ferrari today as their new car was prepared! Imagine Ferrari letting them!! Peter Collins won the International Trophy at Silverstone in the 250F from some staunch opposition, an important win for him, and then retired it in the British Grand Prix. With the BRM engine producing some 260 bhp, it was decided to debut it at Aintree for the Daily Telegraph Trophy race where Peter Collins was giving it a promising first showing until it crashed early in practice and was withdrawn. This was chassis 252, and it turned out that oil-scavenging problems had caused the breather to pump oil onto the rear tire!

Collins then drove the repaired 252 at the Oulton Park Gold Cup three weeks later, was only 13th fastest on the 4th row, but proceeded to fly up through the field into 3rd place. Then the oil pressure gauge went to zero and Collins retired, and later the team found that the gauge’s needle had unscrewed itself! Collins was signed for Ferrari in 1956 so Tony Brooks and Mike Hawthorn became the new BRM drivers. However, this season was also pretty much a disaster. Engine and brake problems dogged the team, and the single rear brake ate up pads at an alarming rate, so a reduction gear was built in to reduce the disc rotation speed. The cars had absolutely fierce acceleration, but the front struts wouldn’t work until the car had run some laps. At the British Grand Prix, Tony Brooks had his famous crash when the throttle stuck open and the car rolled. Brooks said the car “did the decent thing and burned itself out.” That was the end of 252.

From the beginning of the P25’s career, in 1955, until the end of 1956, the cars had only managed eight starts and one finish. Alfred Owen ordered an end to racing until a thorough test and development program had been run, which started late in 1956. Both Colin Chapman and Alec Issigonis contributed to substantial suspension changes for 1957. The whole project had echoes of the V-16…and that is not a compliment. BRM used drivers Roy Salvadori, Ron Flockhart, Les Leston, Jack Fairman, and American H. MacKay-Fraser in 1957, and they achieved very little. Chassis 254 had been completed in September 1956, but Flockhart wrote it off at Rouen in July 1957. Chassis 253 had been the first, “second series” stressed-skin car, 254 the second, and 255 the third and last.

Jean Behra secured the loan of 253 for the Caen Grand Prix, a nonchampionship event, and the little Frenchman tigered the BRM to pole position and BRM’s first win in the 2.5-liter formula. Harry Schell drove the second car, and Behra and Schell would become a formidable team for BRM. For the International Trophy in September, Behra, Schell, and Flockhart were in 251, 253, and 255. Though Tony Brooks had put Rob Walker’s Cooper on pole, Behra won one heat, Schell the other, and they were 1st and 2nd in the final with Flockhart 3rd. This race provided the boost BRM needed to carry on.

The old chassis was put aside for 1958, and a lighter space frame replaced it, with removable body panels, unlike the earlier cars. A fifth main bearing was added to the engine, though this wasn’t particularly successful. Perhaps not surprisingly, Behra wrote off 253 early in the season at Goodwood as both his and Schell’s cars had brake failure. At Zandvoort in late May, Schell in 257 and Behra in 256 were 2nd and 3rd, the best results so far in a championship race, though Behra was unhappy about the lower power output after the fifth main bearing had been added. The power had dropped from 280 bhp on methanol to 240 on AVGas. Schell then managed 5th at Spa in 257, while Behra retired.

Chassis 258

Chassis 258 was the third car built in 1958 and was completed in the summer, in time to race at the French Grand Prix. Chassis 258 differed from the other two cars running that season in that it had a new-style oil cooler on the right of the engine, instead of the heat exchanger used on the other two. That was the only difference, being in all other respects a straightforward, space-frame P25 with the removable body. With Schell in 258 at Reims, Behra was in 257, while Maurice Trintignant drove 256. Although Hawthorn and Musso were fastest in practice in the Ferraris, Schell got away with Brooks in the Vanwall, until the two Ferraris went past. On lap 10, Musso tried to match Hawthorn and crashed to his death on the right-hander at the end of the long pit straight. There was a fierce battle between Schell, Behra, Moss, and Fangio in his last Grand Prix. The three BRMs eventually all retired, while Hawthorn won from Moss.

Harry Schell was again on the front row at the British Grand Prix in 258, barely slower than Moss in the Vanwall. The early laps saw Collins, Moss, and Hawthorn battling for the lead, with Schell leading the chase until his oil temperature went up and he slowed to come in 5th, while Behra retired 257 with a puncture. Schell and Behra in 258 and 257 both retired at Caen and neither of the pair in 257 and 256 finished at the Ring. The same two cars went to Portugal, where Behra was 4th and Schell 6th.

Swede Jo Bonnier joined the BRM squad for Monza and Morocco at the end of 1958, where he drove 258 for the first time. Behra and Schell were in 256 and 257 and all three BRMs were on the third row at Monza. Schell was rammed by von Trips at the start, and Behra and Bonnier were soon 5th and 6th. Bonnier retired with a small fire at 14 laps, and Behra with no brakes—again—at 42 laps. In Morocco, Behra was on the 2nd row (256), Bonnier on the 3rd in 258, Schell on the 4th with 257, and Flockhart further back with the new 259. Bonnier brought 258 to the finish in 4th spot, a very good showing for him. The race was overshadowed by Lewis-Evans’s accident, which proved to be fatal. It was also Hawthorn’s last race before retirement and his death a few months later in a road crash. Those were hard days.

At the beginning of 1959, Schell and Bonnier were 3rd and 4th at Goodwood in 257 and 256. At Aintree, Schell was in the new 2510. This car and 2511, the last cars built, had new, lighter chassis and more modifications to the brakes. In fact, these two cars were then the fastest front-engine cars seen in 1959. Schell retired at Aintree, while Stirling Moss was in 2510 at the International Trophy with Flockhart in 256. Moss was on pole and looked like he would disappear, but sadly the brakes did the disappearing—yet again—on lap 3, though Flockhart managed a 3rd. Moss was prompted to say, some years later, that the P25 “really was a bloody good car…perhaps the finest front-engine Formula 1 car ever built….” At Monaco, Bonnier was the quickest but 256, 257, and 259 all retired.

Photo: Ferret Fotographics

Then came the Dutch Grand Prix on May 31, 1959. Jo Bonnier had rather amazed everyone by putting 258 on pole position. Brabham set the same time in the Cooper, but Bonnier did it first with Moss next in another Cooper T51. Masten Gregory got a Cooper into the lead at the start but was soon passed by Bonnier and Brabham. Brabham led briefly and then Bonnier dominated until the slow-starting Moss caught and overtook him. When Moss stopped, the BRM sailed away to win BRM’s first World Championship race in ten years of trying. Even the rival teams were pleased for BRM.

Brabham won the British Grand Prix from Moss in the now-BRP-liveried 2510, while Schell was 4th in 257, Bonnier retired, and Ron Flockhart had spun and retired the new 2511, the very last P25 built. The German Grand Prix was run at the dauntingly fast AVUS track, where Bonnier (258) and Schell (259) were 7th and 5th in the first heat, and reversed that in the second heat giving Bonnier 5th on aggregate. This is the race in which Hans Hermann, in the BRP 2510, crashed in heat two, deposited himself on the ground and—chronicled in a now-famous photo—sent the BRM flying over his head to destruction.

Flockhart was 7th in Portugal in 258, and then Bonnier drove it to 8th at the Italian GP at Monza, behind Schell. Flockhart won a race in 2511 at Snetterton with Bruce Halford 3rd in 259. In 1960, Bonnier was 7th in 258 in the Argentine Grand Prix, and 6th at the Goodwood 100.

Chassis 258 then went back to Bourne where it was restored. It is the only original P25 to survive, and still has its original frame number, 273, on it. Chassis 251, 252, 253, and 254 were all written off. Chassis 255 was dismantled and the parts put on the stock shelf; 256 and 257 were broken up and the parts used in the rear-engined P48. Chassis 259 was broken up in 1960, 2510 written off by Hermann, and 2511 also broken up in 1960. Chassis 258 was used for promotional purposes from 1960, and did demonstrations at historic events. It was sold with most BRM stock at the famous Motor Fair sale of 1981, to the Hon. Amcshel Rothschild who raced it through the 1980s and 1990s. When he died, it was bought by Spencer Flack, who very sadly died in an accident with the car at the Phillip Island Historics in Australia. The car is now in the possession of the Flack family, and it was with their agreement that I was able to compete with it at the Goodwood Festival of Speed.

Driving 258

When Speedmasters’ James Hanson said the Goodwood drive was on, I really couldn’t believe my luck. Stirling Moss had said what a great car this was. Tony Rudd himself thought 258 was the best of the P25s, and he said Bonnier had said the same thing.

In spite of the amount of time I had spent at the Goodwood Festival as reporter, photographer, and commentator, this was my first appearance as a competitor. It was all well and good doing tests here on preview days, with a very informal atmosphere and no spectators, but Friday of the festival now has tens of thousands of people everywhere in the grounds of Lord March’s Goodwood House. It all changes when you are at the center of huge numbers of people who want a good look at the car, you, and everything going on. The Formula One paddock where the BRM was located and looked after by Speedmaster Cars and Hall & Hall was packed—I mean really packed, with endless numbers of knowledgeable passers-by coming to relate their own tales of the BRM.

Richard Attwood, Brian Redman, and former Porsche competition boss Norbert Singer were only a few of the many who came to give me a serious working over on my “debut”—mostly warning me not to wreck a very famous car!

I suppose it was fortunate that I had to focus on the Goodwood Radio task of bringing back a recording that was intelligible. The Hall & Hall team was attentive to the nth degree, so I was clear on the procedure before I turned some attention to the microphone taped to my chin! The BRM started with ease, and I found my way around the four-speed gearbox with no difficulty, in fact the gearbox on this car is a delight to work with, amazingly smooth and reassuring. I was worried about finding reverse because at Goodwood; you exit the assembly area with all the other cars and make your way down to the starting area. It’s very narrow down there and I could see myself failing to find reverse as I did six-point turns, overheating and wearing out the clutch. But somehow P258 instilled a sense of confidence. I did a quick turn, flicked it into neutral, let it roll back, ignored reverse, and got in line for the start.

There is nothing quite like a BRM exhaust note. The P25 isn’t as shattering as the V-16 was, but it is noisy, though sweetly so. When it came my turn to run up to the flag, 258 restarted with no fuss, and no stalls. A quick glimpse at the rev counter to get a smooth but proper start, down came the flag, up went the revs, and amidst a cloud of just enough tire smoke, 258 launched off the line.

As I flicked back to second gear, all the stories of the torque from the BRM 4-cylinder flashed through my mind. Trying to speak into the mike, I was also careful to get third gear right as I bore down on Goodwood’s tricky first corner, a double right-hander taken in third. I had been told that there was plenty of feel at the back, so I took the chance of keeping my foot in through the corner, and holding it there on the exit. The back came out a touch, a nice bit of oversteer, and the revs went up…to about 7,500…a long way from the 10,000 on the dial! The car straightened up nicely and was now heading up past Goodwood House on the left, with the packed grandstands on the right. Under the bridge, the exhaust “blatted” superbly. Now in fourth, the acceleration was indeed impressive, shot past my colleagues in the commentary tower, saw a wave from Neville Hay, and headed into the not-so-easy left that would lead toward the uphill bit.

Could the brakes cause trouble here, as they had so often in the past? Remember Behra wrote a P25 off at Goodwood! Discretion seemed advisable, so down to third I go and a fairly easy line around to the left, a place where many first-timers have gotten into embarrassing trouble. But then the rest of it was quick…one more drop down from fourth to third but then flat out in top all the way, the pebble wall eerily close on the left-hand side. The torque carried the P25 rapidly toward the top, bringing a wave from marshals and spectators standing at all the interesting points the whole way up the hill. The last bit of the run is very fast, the sound reverberating off the solid wall of trees, downshifts echoing for a long, long distance, as the finish line is passed and it’s time to test the brakes again as the collecting area comes into view.

People come over for an opinion and I have an irrepressible grin. Fortunately, there will also be the chance to go down the hill and experience it all again. In between there’s time to think of Jo Bonnier, Harry Schell, Ron Flockhart…and Spencer Flack. This is a great and rare car.

Specifications

Chassis: Space-frame with permanent undertray for stiffness, in steel with alloy body

Wheelbase: 90”

Weight: 1,521 lbs.

Engine: 4-cylinder inline, 2 valves per cylinder, DOHC

Displacement: 2497 cc

Bore/Stroke: 102.87 x 74.93 mm

Power: 248 bhp @ 9000 rpm

Fuel feed: Twin Weber carburetors

Gearbox: 4-speed

Steering: Rack and pinion

Brakes: 3 outboard Dunlop discs, 2 front and one centrally mounted at rear

Suspension: Front – double wishbones with coil springs over dampers; Rear – de Dion, coil springs over dampers, oleo pneumatic struts

Resources

Thanks to the Flack family, Hall & Hall, and James Hanson of Speedmasters.

Nye, D. History of the Grand Prix Car 1945 – 1965 Hazleton Publishing, 1993