1952 Ferrari 225 S

While the history of the Ferrari you see here will forever associate it with the great American World Champion Phil Hill, this particular car is much more important for its symbolic significance. In the early 1950s, Enzo Ferrari had his eye on America, and very few of his products of that time came about without the notion that they might do well in the new American sports car buying market. The 225 S was one of the cars that helped pioneer Ferrari’s opening up of what would turn out to be his most lucrative and lasting market.

I have always found the books about Ferrari interesting from several points of view: the ones about Enzo Ferrari himself have almost always viewed him in at least semi-heroic terms; the ones about the cars have usually divided them clearly between road-going machinery and racing cars. The reality is that, especially in the late 1940s and early 1950s, most non single-seater Ferraris were dual-purpose machines. Enzo Ferrari wanted to build and sell production cars for road use, but very few of the designs of that period could not be turned into racing cars. One can argue that Ferrari’s legend really evolved from the fact that virtually all his cars were, indeed, racing cars.

Ferrari’s original identification system for his cars included the division into two groups: the corsa or competition cars would have chassis numbers ending with an even number, and the stradale or road cars would get an odd final digit. However, if you peruse all the early 166 MM barchettas and berlinettas, the 195 Touring coupes, you will find that the bulk of the stradales were raced, and many of those sold as racecars soon became road-going machines for the more affluent. That was what made Ferrari Ferrari!

The other aspect of car production in the period was that wealthy owners could specify what they wanted done to their cars, so there was a wide range of “options” that would allow many cars true dual-purpose use. It is very interesting, then, that the 225 S cars produced all had chassis numbers ending in an even number. Obviously this was going to be a model that might cause the historians a few headaches!

Stanley Nowak, in his book Ferraris On The Road, doesn’t deal with it at all, so he didn’t consider it a road car. Dean Batchelor, in Ferrari—The Early Spyders and Competition Roadsters, didn’t consider it a competition car. Godfrey Eaton’s The Complete Ferrari has it down as an “interim car” in his section on V-12 sports racing cars, and Hans Tanner’s “masterwork” hedges its bets by showing a photo of the 225 S in the road car section without a description, and gives details in his chapter “The Sports Cars,” by which he is referring to the competition cars. So that should really make “our car” a true, dual-purpose machine!

The 225 S was indeed an important, though lesser-known, part of Ferrari’s early history. The original 125 S, the 166 Spyder Corsa and 166 Sport were produced in 1947. In 1948 we had the 166 Inter and 166 MM. The 275 S appeared in 1950, along with the 195 S and the 195 Inter, while 1951 brought the 212 Inter and Export and the 340 America. Along came the 225 S in 1952, a year that also witnessed the production of the 225 Inter, the 250 S, the 340 Mexico, and the 342 America. Some of these cars were built over a period of two, three, or four years, but the 225 S was only made in 1952.

John Godfrey was right in describing the 225 S as an interim car, though it was rather more than a link between two similar models. It was the link between the cars that had established Enzo Ferrari as a car constructor, and those which would guarantee the future. The 225 S predecessor was the 212 with a 2512-cc engine; the 225 S had evolved to a 2715-cc unit, and the next car would be the 250 S, the first of the 3-liter cars that would bring Ferrari worldwide fame. There are varied opinions on how many cars were built. There seem to be records for 15 spyders, all but one of which had bodies by Vignale, with the exception having a Touring barchetta body. There were seven Vignale berlinettas.

The intention when this car was designed—the S in 225 S stood for Sport—was that it would be sold primarily as a competition machine to privateers, and that it would be used to develop the next, 3-liter car. Much of Tanner’s section on the 225 S is actually taken up with the car that became the 250 S prototype, and in which the new engine was used. Bracco, having consumed large quantities of Chianti and brandy during his drive, won the 1952 Mille Miglia in chassis #0156, which had a 225 S type body but was officially the 250 S prototype. Biondetti drove a more conventional 225 S in that race.

In order to make the 225 S competitive, the Colombo short-block engine was bored out to bring the capacity to 2715-cc. Though the character of the engine was retained in Giacchino Colombo’s style, some of Aurelio Lampredi’s ideas were used in the development, such as roller-type cam followers. Twelve-intake-port heads were used in most, though apparently not all, the engines. The 225 S engine thus managed to give 210 bhp at 7200 rpm, an increase of some 50 bhp over the 212. Some of the cars, about half a dozen, featured what was called the “Tuboscocca” chassis. This had double outer chassis frame tubes, one above the other. Additional tubes formed an outline framework to which the body was mounted. This tubing could be changed to match the type and shape of body to go onto the chassis.

Photo: Peter Collins

The very first chassis, #0152EL, a berlinetta, was immediately successful in the hands of “Pagnibon,” the nom de plume of Pierre Boncompagni, and in early 1952 he won at Montlhéry, Nimes, the val de Cuech hillclimb, and Bordeaux. He was 5th at the Sports Car Grand Prix at Monaco that year, and although he retired at Le Mans, that first car had some very good results, prompting other privateers to put their money down. Vittorio Marzotta bought #0154ED, a spyder, and it was his car that won the Monaco race that year, when the GP was for sports cars. Biondetti’s non-finishing car at the Mille Miglia was #0160ED. Franco Bordone was 10th overall in the Mille Miglia, and then Jean Lucas had a number of French wins in #0164ED.

Eugenio Castellotti proved his growing abilities by winning the Coppa d’Oro di Sicilia in March 1952 in #0166ED, which was the lone Touring-bodied barchetta. He was also 5th in the Giro di Sicila, didn’t finish at the Mille Miglia, and was 2nd at Monaco. That car moved on to Bill Lloyd and then Briggs Cunningham. Paolo Marzotto bought #0172ET, and although he also did not finish the Mille Miglia, he managed wins at the Coppa d’Oro della Dolomiti, the Giro della Calabria, and at Senigallia. Antonio Stagnoli had #0176ED, an unusual one-off chassis with fenders rather than a one-piece body. He and Biondetti were 3rd in this car at Monaco, and it enjoyed a long and successful racing history.

A review of all the individual chassis reveals that just about every 225 S did some serious races when they were new, and most of them had very satisfying results. Bobby Baird from Northern Ireland bought #0214ED, which he raced a number of times with Roy Salvadori. Froilan Gonzales brought #0216ED to Argentina and sold it to Senors Mendoza and Maiocchi, with the latter racing it three times in the Buenos Aires 1000 Kilometers, finishing every time.

Chassis 0218ET

Photo: Pete Austin

“Our” car, #0218ET, came near the very end of the batch being produced in 1952, 22nd of 23 cars. It was ordered by Alfred Momo, who was importing Ferraris to America at that early stage, though he is less well remembered than Luigi Chinetti. The car was ordered for William “Bill” Spear who was at the time living in Manchester, New Hampshire, and was becoming a strong supporter of sports car racing both as a driver and an entrant. As this was at the end of the car’s production, it didn’t get into Spear’s hands until September or October of 1952. He entered it for himself at the Sowega National Sports Car races at the Turner Air Force Base near Albany, Georgia on October 26.

These were very much the early days of sports car racing in the USA, especially on the east coast. There were three events on the fast, 4.5-mile runway circuit: a race for smaller production cars—MGs, OSCAs, Porsches, and a handful of Morris cars. Then came a second short race for larger machines, and finally the main event, the four-hour Strategic Air Power Race that would be 342 miles. It attracted a strong entry of more than 40 cars, of which several ran in the shorter races. Thirty-one of them managed to qualify as finishers. J. Simpson won the Keenan Sowega Trophy in an OSCA, and George Huntoon’s Jaguar XK120 took the M.W. Tift Pioneer Trophy.

Photo: Ozzie Lyons / www.petelyons.com

The main race was led most of the way by the Chrysler-powered Cunningham of John Fitch who won without a stop, but was only 32 seconds ahead of the Jim Kimberly Ferrari of Marshall Lewis who stopped for tires. Huntoon brought his Jaguar home 3rd, from Fred Wacker in a Cadillac-Allard. Then came Bill Spear in the rather smaller-engined Ferrari 225 S, a positive achievement on a track that called for all-out power. The 225 S was timed at 149 mph through the speed trap, compared to the 168 mph of the Cunningham.

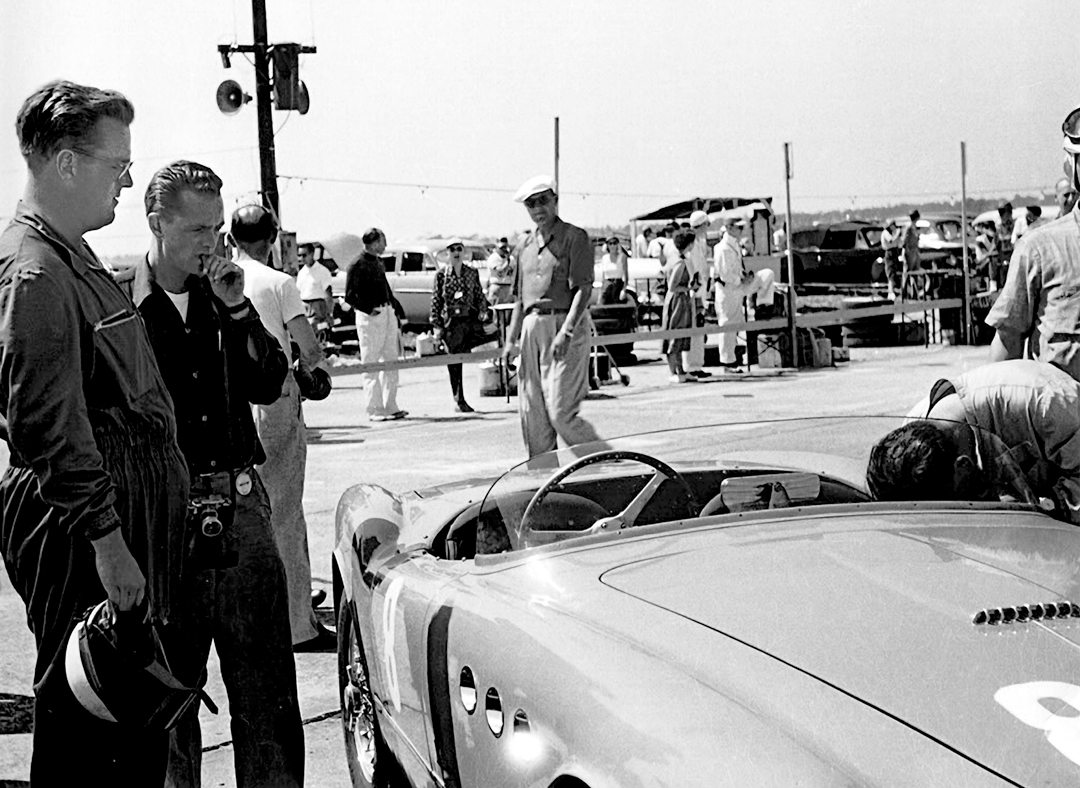

At the beginning of 1953, Sebring race organizer Alec Ulmann had managed to convince the FIA that the very first round of the Sports Car World Championship should be at Sebring. There had been a six-hour race in 1950, and the first 12-hour in 1952. Now Sebring suddenly became famous. The international entry was not sensational, but it was good. John Wyer brought the Aston Martin team from the UK, with cars for Peter Collins, Reg Parnell, George Abecassis, and Geoff Duke. Briggs Cunningham entered a CR4 for John Fitch and Phil Walters, and there were four Ferrari 225 S entries for Jim Kimberly and Marshall Lewis, Peter and Robert Yung, and the Bill Spear entry for himself and an up and coming young Californian, one Phil Hill.

It was clear from the start that the race would be between the Cunningham and the Astons. Peter Collins led for the first three hours and had a big gap to the Cunningham when he handed over to Geoff Duke. Duke soon got in a tangle with a slower car, over which Collins threw a fit, but they were out. The Cunningham led from then on to beat the other Aston of Parnell/Abecassis. Hill and Spear were 5th behind Kimberly’s 225 S at the end of the first hour, then moved into 3rd. The car ran in 4th at the end of the next two hours, the leading Ferrari. Then in the fifth hour the car ran off the road when it began to have brake problems. This could have been sorted, but the car struck the foundation of an old building hidden in the tall grass and was out. The accident managed to rip off the anti-roll bar Alfred Momo had fitted to improve the handling. The Yungs’ 225 S finished 8th, five laps behind a Ferrari 166 MM. Though this was Phil Hill’s only outing in the car, he had demonstrated that a good driver could more than make up for the difference in engine size, and the 225 S was a well-built and reliable car.

Bill Spear did a number of races in the car during 1953. On May 30, he was 1st in a preliminary race at Thompson Air Force Base and 2nd in the main event. On July 4th, Bill Lloyd drove it at Offut AFB, getting 4th in the preliminary and 7th in the main race. In August, Spear drove #0218ET in two races at the Lockbourne AFB races at Janesville, finishing 10th in one and 4th in the other, behind Kimberly’s 4.1 Ferrari, Masten Gregory in a Jag XK120C, and Ed Lunken’s 225 S. Spear then had a clear win in another race at Thompson in Connecticut. Bill Lloyd finished the season winning the Sowega race at the Turner AFB event.

Photo: Ozzie Lyons / www.petelyons.com

At the end of 1953, the engine was removed and replaced by the similar unit from chassis #0152ET. Bill Spear raced it along with Bill Lloyd and Sherwood Johnson into 1954, when it was sold to Adrian Melville. Melville entered #0218ET for the Savannah Cup national races in March 1954, running in the 150-mile Savannah Grand Prix at Hunter Air Force base in Georgia. Two 4.5-liter Ferraris were 1st and 2nd in the hands of Jim Kimberly and Bill Spear (with his new car), Bill Lloyd was 4th in another 225 S and Melville was 10th running in the D Modified class.

Melville was also at the President’s Cup race, a 203-mile event at Andrews AFB near Washington, D.C., where Spear won in his 4.5 Ferrari and received his trophy from President Eisenhower. Melville didn’t finish. In September, “our” car was back to Thompson in Connecticut where Melville won the Class D & E Modified race at the SCCA Nationals. Then in 1955, he sold the car to Robert Williams in Florida. Williams entered it at Nassau for the 1955 Speed Week, finishing 10th in class in the Governor’s Trophy, 10th overall in the Alberto Ascari Memorial Trophy race for Ferraris, and 14th in class in the Nassau Trophy. Williams then ran it, finally, at SCCA regional races at Punta Gorda in Florida.

That was effectively the end of #0218ET’s period racing career. It was sold to a Cunningham-owned car dealership in Florida and then it found its way to Hollywood, where it was used in the film business, although it doesn’t seem to have any known films to its credit. (Keep looking!) At some point it acquired a Chevy engine and did some drag racing!

It was in very poor condition when Steve Morse bought it, having paid a reputed $2500 for a basic chassis, body, suspension, the wrong rear end, and no instruments. Gary Schonwald, a New York collector, bought it for around $10,000 as he had already acquired the original engine. Schonwald did a meticulous restoration, and the car then passed through the hands of a series of owners. It returned to the UK in 1996, and was owned for a short time by Carlos Monteverde. It did several retro Mille Miglia events in the 1990s, and for the last ten years has been very well maintained, now possessing its original engine and 5-speed gearbox.

Driving #0218ET

To anyone unfamiliar with Ferrari’s early products, this car does not look like a competition car. The beautiful Vignale body tends to make #0218ET look like a top end concours machine—and indeed it is. Now this car has benefited from very close attention, but unlike some of Enzo’s ’50s road machines, this car is amazingly civilized. I have driven a number of road cars of the period—the 250 MM and Europa, a 340 America—and some of them were hard work. The clutch could be heavy, the steering even heavier, they overheated, there were lots of rattles. However, this was a racecar, and it was totally without any of these vices.

It was interesting that we were testing this car at Goodwood on the same day that I was driving the Le Mans-winning Aston Martin DBR1 from 1959 and John Surtees/David Hobbs 1967 Le Mans Lola-Aston Martin. Those were cars that required all your attention and looked and felt like full-blooded racecars. When it was time for the Ferrari, it was a moment of relaxation and pleasure—like stepping into a softly burbling Jacuzzi. The interior, in beige leather with lovely period bucket seats, and the superb tidy cockpit, with a shiny red dash were all so luxurious—but minimalist. There is, of course, the Ferrari 3-spoke steering wheel with its prancing horse, and only two large gauges. There is a speedometer to the left reading to 240 kph and a rev counter up to 8500 rpm. On the right of the wheel are small temperature gauges and the ignition switch. There is a handbrake lever to the right, and the gearshift to the left with its sculpted wooden knob, a few switches, and that is it.

I took the time to have several tours around the car before starting off. It is a classic period Ferrari, the beautiful well-balanced Vignale lines making it look as good as it was. There are triple chrome air outlets on either of the front wings—a Vignale trademark—a purposeful front grill, and chromed air vent on the bonnet. The attention lavished on this car is evident. Everything is well put together, tight, functional; there are no creaks or groans.

When it came time to get moving, the seats wheezed a bit as I slid in. Turn and press the key and the V-12 comes to life immediately, that historic sound bursting out of the two exhaust pipes at the rear. There was no need to hunt around for gears—this gearbox is tight and responsive—and I did my best to try out all five gears on the way up Lord March’s hill. There’s a nice steady breathing sound from under the bonnet as the well-tuned triple Weber 36 DCL3s do their job. The throttle was quick to respond, with no heavy prodding needed—someone has done a good job with the linkage!

Though we were managing to do our test during one of Lord March’s talks to the press, describing the upcoming events at Goodwood, and therefore had to maintain some decorum and silence as we slipped down the drive from Goodwood House, we quickly got round the corner and headed for a first run up the famous hill. Now, this was never a hillclimb car, and this is a very narrow bit of road. Nevertheless, the 225 S is sure-footed and immensely stable, even under pressure.

I was immediately impressed by the good manners, and lack of fuss. The torque is there to assist, and with a bit of lean, the car took the first left past the house and accelerated rapidly through the tree-lined route. Past the well-known and lethal looking pebbled wall, it was up to 3rd, 4th and then 3rd again through the twisty esses at the halfway point. A good press on the throttle, and the revs and the glorious sound rose to 4th and top for a flat-out run to the top. Five thousand rpm in top gear—well, that was quick!

I had the luxury of a few runs, and a chance to work the drum brakes, more on the way down than up. They didn’t pull, nor make a sound. It was all very steady going. The real thrill, however, was to be able to set off up that totally empty hill and listen to the music of the V-12 echo off the trees and banks, absorbing both the power and the extravagance of this great machine. The independent front suspension makes the 225 S so predictable and manageable that you can really get the best out of a car in which most people might be frightened to use a few extra revs.

There must be few vehicles manufactured as competition cars that make such perfect road cars. I think this 225 S even begins to push the California Spyder for aesthetics, and that is saying something. This car, though, does beat it on history—truly Enzo’s connection between past and present.

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis: Tubular steel frame

Suspension: Front: independent double wishbones, transleaf spring; Rear: rigid axle, semi-elliptic springs

Wheelbase: 2250 mm

Track: Front: 1278 mm; Rear: 1250 mm

Engine: 12 cylinders, single overhead cam per bank, single plug per cylinder

Capacity: 2715 cc

Power: 210 bhp @7200 rpm

Bore and stroke: 70 x 58.8 mm

Compression ratio: 8.5 to 1

Gearbox: 5-speed integral with engine

Brakes: Hydraulic drums

Tires: Front: 6.00-16 Rear: 6.00-16 Blockley Tires

RESOURCES

Many thanks to Martin Chisholm and Will I’Anson at Martin Chisholm Collectors’ Cars (www.martinchisholm.com) for making this car available, and to Lord March for the use of the Goodwood hill.

Eaton, G. The Complete Ferrari Cadogan Books UK 1986

Tanner, H. Ferrari 6th Edition Haynes Publishing UK 1989

SportsCar – The SCCA Magazine