Alfa Romeo TZ2

By 1963, Alfa Romeo was looking for a replacement for their Giulietta SZ, which had been very successful in European racing and rallying. It had heralded Alfa’s first use of Girling front disc brakes and had seen inroads made in aerodynamic technology with efficient use of the sharply cut-off Kamm tail, which improved top speed.

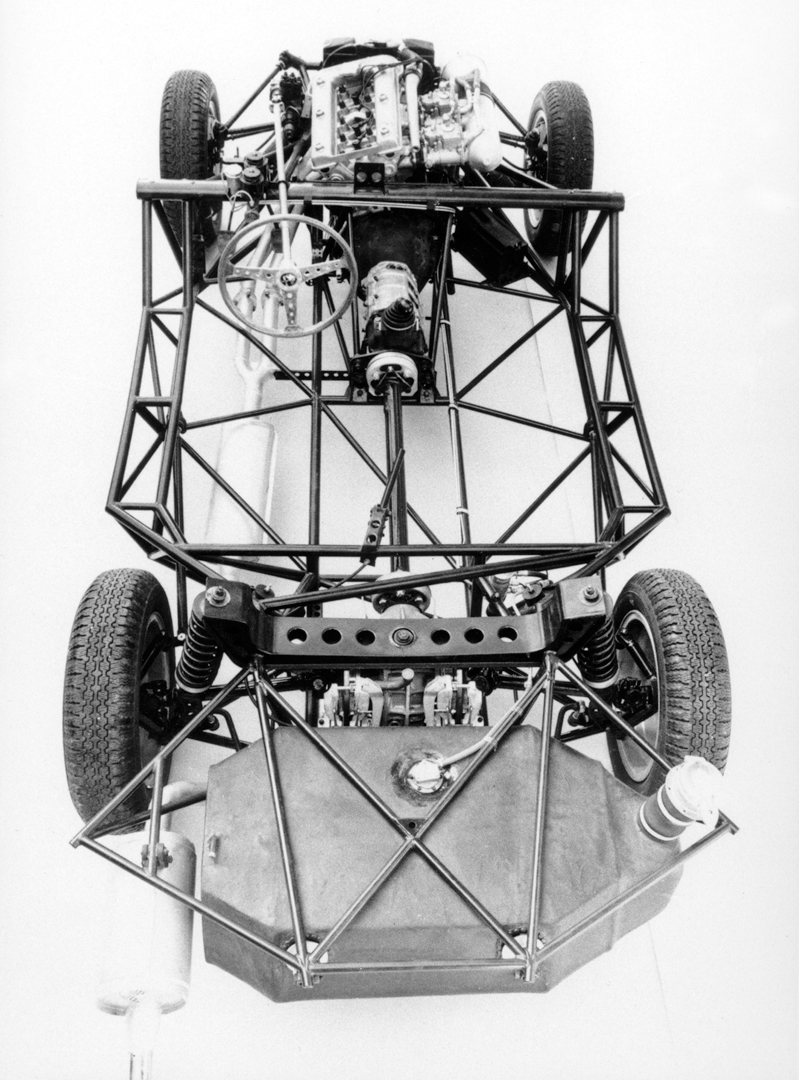

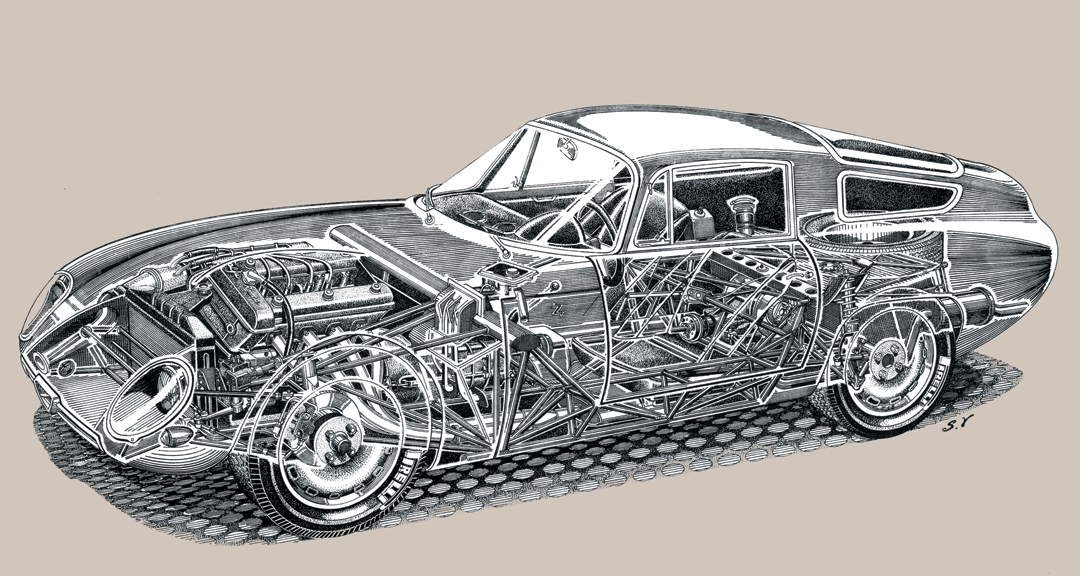

So the Giulia TZ appeared in 1961, or as it has become known, the TZ1, to distinguish it from its successor the TZ2. The TZ1 was a sophisticated and well-thought-out machine, in comparison to the earlier Giulietta, and had been designed with racing as a key part of its nature. As part of that racing nature, the TZ utilized the Giulia 1570 cc engine, which could produce 112 bhp, as well as a relatively sophisticated tubular space frame (the T in TZ stood for tubolare), and a very shapely and aerodynamic bodywork to cloth the chassis and independent rear suspension (the Z in TZ stood for Zagato).

The next phase in the story is an interesting one. In order for the cars to be accepted for homologation in the sports category, at least one hundred examples had to be produced. In order to achieve this, Alfa Romeo, very busy with a number of new production cars, farmed the work out to the Chizzola brothers in the northern Italian town of Udine, and they established a separate company to build the cars. Their new company was called Delta, though subsequently the name was changed to Autodelta. The engineering and design consultant to Autodelta was a gifted engineer by the name of Carlo Chiti, a man whose name would become synonymous with Alfa Romeo and racing from that point on.

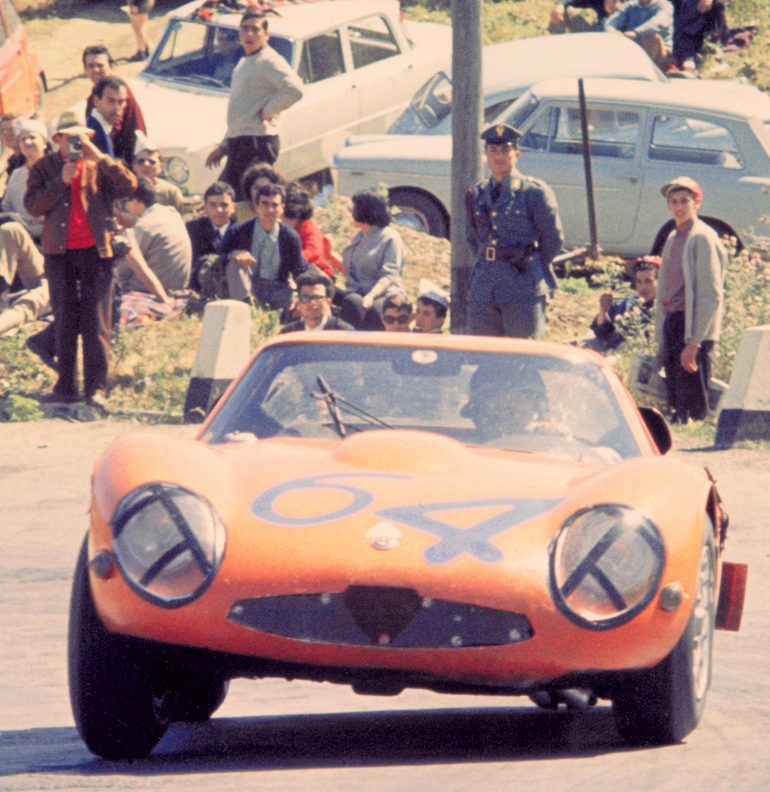

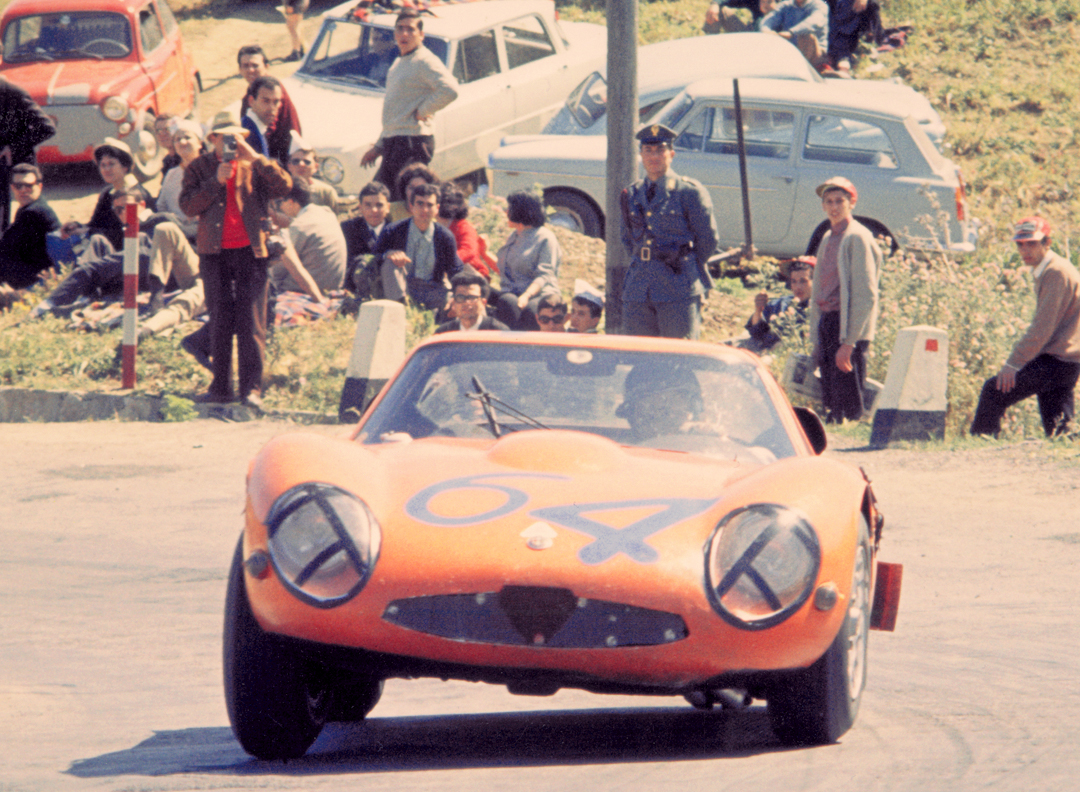

Photo: Marouf Collection

Most of the early TZ1s were race prepared in Milan and raced by Scuderia Sant Ambroeus or the Jolly Club. Considerable early sorting was required as the first roadster prototype was a handful and slower than the Giulietta SZ. The rear suspension was substantially modified and the coupe body added to make use of the aerodynamic possibilities. Class successes in racing came easily with many victories at Monza from 1963 on. And in 1964, there was a class win at Le Mans for Roberto Businello and Bruno Deserti. Businello, who died in 1999, was interviewed in 1992 by Ed McDonough and described the TZ1 as “an always difficult car to drive….it was dangerous,” an opinion shared by many of its drivers as the handling was rather unpredictable. The TZ1 also did well at Sebring and the Nurburgring 1000 Kms., and it was also a successful rally car, winning its class in the Tour de France.

Despite the success of Alfa Romeo’s TZ1 racecar, it was clear by 1964 that the original design, which had been conceived in 1959 but not completed until late 1962, was becoming obsolete and wouldn’t be able to keep up with the opposition much longer. Rather than build an entirely new car, Alfa decided to update the existing design. The result was the lighter, lower, and much faster TZ2.

Alfa built the TZ1 to give private racers a competitive, but uncomplicated racecar that was easy to maintain and relatively affordable to run. Its success in international GT racing produced valuable publicity for the company and its line of Giulia production cars, from which the TZ1’s running gear had been taken. The TZ2, however, was intended from the beginning to be an Autodelta-built and works-operated venture.

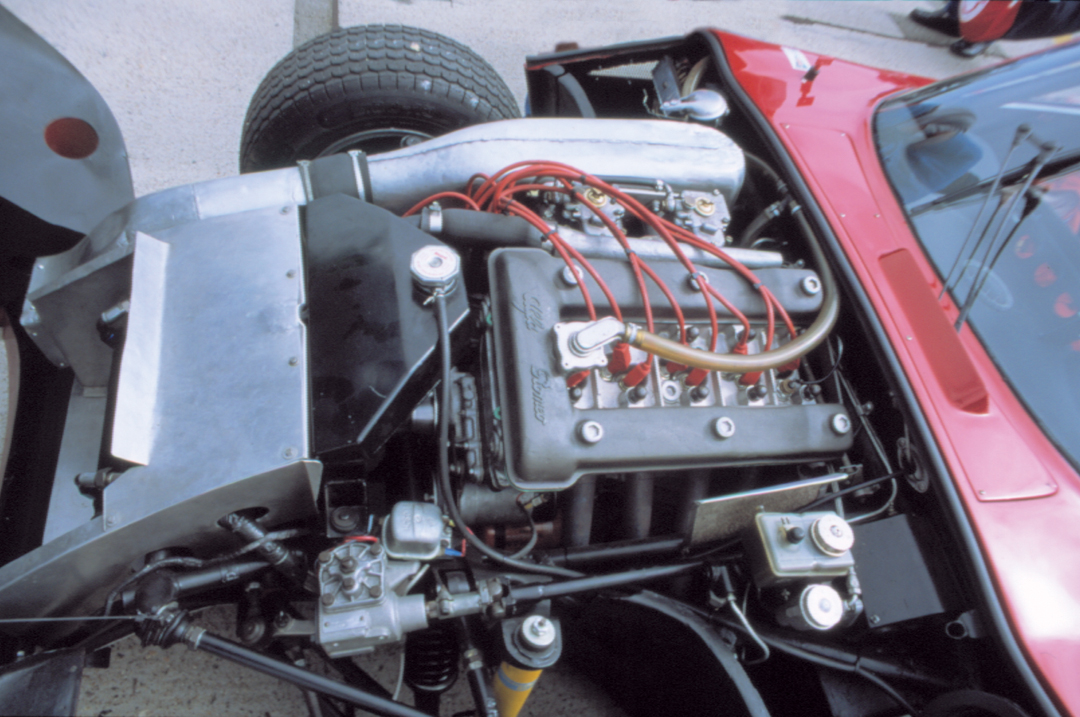

The TZ2 kept the TZ1’s tubular chassis, independent suspension, and four-wheel disc brakes. The lovely twin-cam 1600, an all-aluminum engine that produced 112 horsepower in the production Giulias and 150 in the TZ1, was fitted with a twin-plug head, lighter pistons, and bigger valves, boosting the power to 170 horsepower at 7,500 rpm.

Photo: C. Annis

Several things were done to lower the car. Its 15-inch wheels were replaced with 13-inch wheels, and a lower roof height was achieved by reclining the seats and reducing the angle of the steering column. Additionally, a new dry-sump system let the engine lay deeper into the chassis, allowing a lower hood and improved aerodynamics.

To reduce weight, the TZ1’s aluminum body was replaced with a lighter fiberglass one. The new body, drawn lower and leaner, looked more aggressive; but thanks to the talent of its designer, Ercole Spada, it lost none of the original’s grace. All these improvements resulted in a car that sat 140 mm lower, produced 20 extra horsepower, and weighed 40 kg less.

Unfortunately, by the time the TZ2s made their race debut at Monza in 1965, Alfa management had already told Carlo Chitti, Autodelta’s director, that his shop was to concentrate its efforts on developing the GTA and the Tipo 33. This was done at the TZ2’s expense, and soon the cars were sold off to privateers. The TZ2 raced successfully for another two seasons and scored class and sometimes even overall wins in a variety of events including sprints, endurance races, and hillclimbs. The TZ2 extended the TZ1’s victories with wins in the 1600 GT class at Sebring, the Targa Florio, the Nürburgring 1000 km, Monthlery, Spa, and Monza.

Denis Jenkinson (Motorsport, 1965) recalled the appearance of the TZ2 in the Targa Florio: “The special bodied orange Alfa Romeo GTZ of Autodelta, the factory team, came screaming into sight at the far end of the village street, and snarled as it slowed and changed down for the corner in the square.” Jenkinson had been sitting in Campofelice, where many sightseers were to get an unforgettable glimpse of the little Alfa tiger. In the Targa that year, Lucien Bianchi and Jean Rolland finished 7th overall and won their class, and in the same year Bolley Pittard was putting in impressive performances with a TZ2 in England.

TZ2s are admired for not only being very competitive racecars, but beautiful ones as well. Besides the well-known Zagato racecar design, two show cars were built on the TZ2 chassis by Pininfarina and Bertone. The beautifully proportioned Pininfarina Sport Coupe Special was shown at Turin in ’66 and was intended only as a design exercise. Bertone’s Canguro, on the other hand, was built with hopes that it would be put into production. Styled by Giorgio Giugaro, the Canguro stole nothing from Ercole Spada’s Zagato design, yet conveyed the Jaguar-like impression of grace and restrained aggression.

It’s a shame that the Canguro was never put into production because arguably it would have been one of the best-looking postwar Alfas. Unlike other exotics of the late ’60s, it would also have been quite practical since the running gear was Giulia based. Several years later, Alfa built the Montreal, a limited-production exotic like the Canguro, but with a V8 engine derived from the Tipo 33 racecar. Not only was the Montreal not nearly as pretty as the Canguro, but the complicated V8 motor was expensive to maintain.

Photo: Centro di Documentazione Storica Alfa Romeo

Today the Pininfarina car is in the Matsuda Collection in Japan. Bertone’s Canguro was badly damaged in the late ’60s after a journalist at a press demonstration crashed another Bertone show car into it. Fortunately, an Alfa enthusiast intending to restore the damaged car was able to persuade the company to let him buy it just before it was about to be sent to the crusher. This lucky man paid $35 for it!

There are constant arguments as to how many TZ2s were built. According to Alfa expert L. Fusi, twelve were made from chassis 750.114 to 750.121, obviously leaving some numbers out. Author David Styles says ten were built, while Hull and Slater say twelve, as does Belgian Tony Adrieansens. Adrieansens argues eight were made in 1965 and four of the 1965 TZ2 chassis were built with TZ1 chassis numbers. For example, 750.104 is a TZ1 chassis number but is an early TZ2. 750.1106 is the same and was one of the early test cars. Possibly 750.112 is the only aluminum-bodied car.

All the nine Zagato-bodied racecars are accounted for and most are in racing condition. Since the running gear is production based, they are relatively inexpensive to run in vintage racing. However, you’ll first need more than a million dollars to buy one, as that’s what the last one sold for at auction.

Karim Marouf Drives The TZ2

Recently, I was fortunate enough to drive one of these rare cars at Willow Springs Raceway in Rosamond, California. The car I drove, chassis #0116, won its class at Spa, Monza, and the Nürburgring.

Chassis #0116 has been fitted with a larger 1750-cc motor that is moderately tuned to produce about 190 horsepower—which gives it about the same power-to-weight ratio as the latest 911 Turbo.

“Fastest Road in the West” is Willow Springs’ motto, and it’s no exaggeration. The TZ2 takes nearly all of the track’s nine corners in fourth or fifth gear. It took me a long time to work up the courage to get up to full speed. The problem with racing #0116 is that even if you don’t care about your own well-being, you’re constantly aware that this is a very valuable, truly historic, and highly original car, one that was in fact never crashed during its entire racing career. I didn’t want to go down in the history books as the chump who’d ruined it.

Fortunately, I found the TZ2 easy to drive. Before I got familiar with it, I entered corners in the right gear, but I was gun shy about really leaning on the gas and building up revs. To my surprise, the highly tuned motor, which was built to make lots of power way up high, pulled strongly even from low revs. And as the RPMs climbed, the power just kept building. So did the noise. A single, unmuffled exhaust pipe exits right below the driver’s door, and when I accelerated down the front straight, the roar of the exhaust echoing off the pit wall was as frightening as it was addicting.

The TZ2 was most exciting in three of Willow Springs’ nine corners. After I became relatively at ease with the car, I could go to full throttle long before the apex of Turn 2, a long sweeper taken at around 100 mph. But I was surprised how much I had to turn the wheel to stay on my line. The car was understeering slightly. In Turn 4, a tight, bumpy right taken in third, the understeer became really pronounced, and even abruptly modulating the throttle wouldn’t get the nose to turn toward the apex. In Turn 8, the understeer really frightened me. This is the fastest corner on the track, and the TZ2 takes it at over 120 mph. Approaching it from the back straight gave me the feeling one gets on a roller coaster that’s just about to go down the other side of a big rise. Before turning in, I redlined in fourth gear, and the shift into top gave a kick like you get shifting into third in a quick streetcar. The car understeered enough that I had to reposition my hands to get more lock on the wheel. There are a few bumps near the apex, and I knew that with so much lock on the wheel, if those bumps were to suddenly knock the tail out, I’d have to do an awful lot of wheel twirling to avoid a huge spin into the desert.

This car’s strong tendency to understeer is not inherent to all TZ2s; this car just needs some chassis tuning. Whenever the tail did slide, it went progressively and was easy to catch, so I’d guess that racing a well-sorted TZ2 is an involving and exciting experience, not an intimidating one.

Photo: C. Annis

To be honest, however, it was a relief to pull back into the pits. Only then, when I wasn’t occupied with keeping this very expensive car pointed shinny-side up, could I appreciate just what a beautiful machine it is.

When you’re sitting inside the car, you look out across sweeping fenders and a long hood topped by a power bulge. It’s similar to the view that I’d imagine you’d see from inside a Ferrari GTO, an Aston DB5, or other classic front-engined GT. A Jaeger tachometer that is as elegant as an old wristwatch is set into the wrinkle-finish dash, with all the necessary gauges positioned around it. This TZ2 has never been fully restored, but its imperfections only confirm its authenticity. Sliding your hands over the steering wheel’s cracked leather, you wonder what hero driver might have had a white-knuckle grip around it some 35 years before.

Chassis #0116 is one of only two TZ2s in the U.S., but it is campaigned regularly, so racing fans have a good chance of seeing it in action. The other TZ2, which is in fact the first TZ2 built, has recently been bought by a vintage-racing enthusiast. We may soon be treated to the spectacle of these two great cars racing together.

Buying and Owning a TZ2

As has been mentioned already, the going rate for a TZ2 is something around a whopping million dollars, not always easy to understand as this is not really an exotic like a Ferrari Testa Rossa. Yet the car is of course immensely rare and has always appealed to racers who like the potency of a competitive car which will take on the big boys. The looks are stunning, though access to repairing the twin-plug head means you have to have connections… these are as rare as the car itself!

Perhaps much of the appeal lies in the time period in which the TZs appeared. The modern racecar was just being born, and new technology was providing big leaps in performance. But these were gutsy and dangerous cars to drive. There have been serious accidents, particularly in the TZ1 with an unprotected steering column that is aimed right at the driver. But if you ever saw one race, TZ1 or TZ2, the appeal is huge and the price seems to follow. With so many vintage series and events on the world calendar, a place for these cars is guaranteed, and hence the demand for the car will follow.

Photo: Centro di Documentazione Storica Alfa Romeo

Specifications

Year of Construction: 1965 to 1967

Body type: 2-seater coupe by Zagato

Chassis type: Tubular

Suspension: Independent

Dry weight: 620 Kilos

Maximum speed: 215 kph

Engine: 4 cylinder in-line

Head: Twin-plug

Bore and stroke: 78 mm x 82 mm

Capacity (standard): 1570 cc., chassis 116 is 1750 cc.

Valves: 2 per cylinder inclined at 80 degrees

Oil system: Dry sump

Carburetors: Twin 45 DCOE Webers

Horsepower: 170 bhp @ 7500 rpm, chassis 116 – 190 bhp

Brakes: Front and rear discs

Wheels: 13″

Tires: Front-550 –13, rear-6.00-13

Gearbox: 5-speed

Resources

Adriaensens, T.

Alleggerita, Corsa Research, 1994, Antwerp.

ISBN- 90-801197-1-7

Fusi,L.

Alfa Romeo Tutte Vettura dal 1910 Emmetigrafica, 1978, Milan.

Styles, D.

Alfa Romeo – The Legend Revived Dalton Watson, 1989, London.

ISBN-0-901564-75-3