1968 Alfa Romeo T33/2

“What goes around comes around.” That, I believe, is a largely English way of referring to “life repeating itself,” or coincidences, or both. This is a bit of a story of automotive déjà vu.

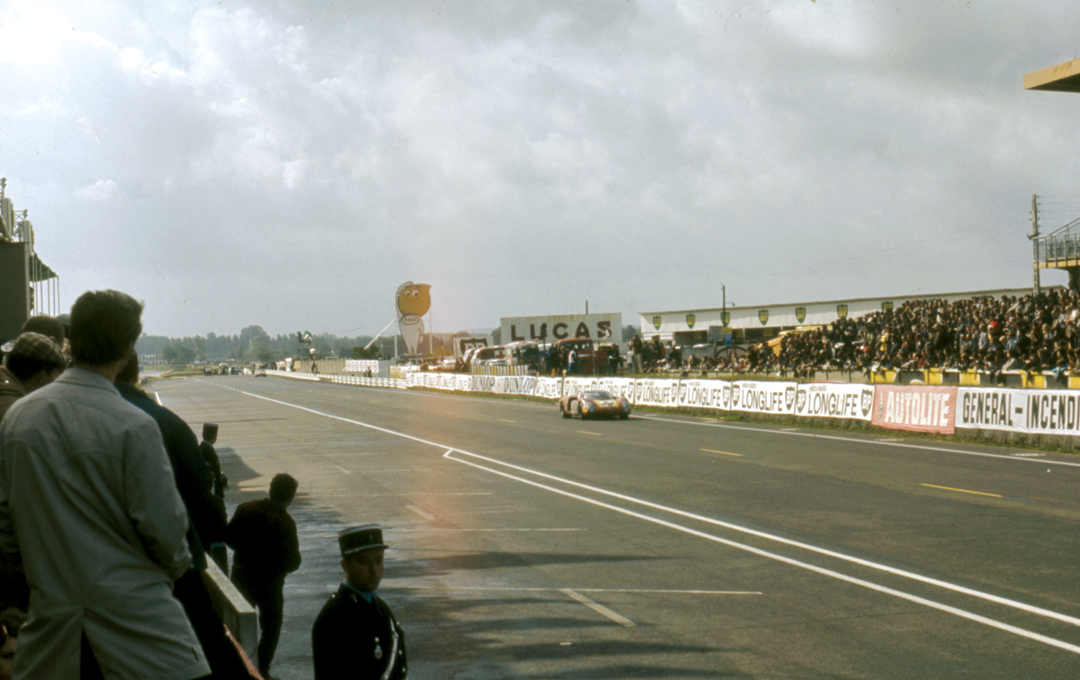

In 1968, I made my first and most memorable visit to the Le Mans 24 Hour race. It was a peculiar year in many parts of the world, and student protests and changed election dates meant the race moved from its traditional spot in June to September. It was a race in which the much-loved Pedro Rodriguez and his co-driver Lucien Bianchi piloted a Ford GT40 with great smoothness and verve to an impressive win. I was on Mike Salmon’s signalling crew down at Mulsanne Corner and had a unique view of the cars. The Matra of Pescarolo and Servoz-Gavin spent many hours screaming around in 2nd place.

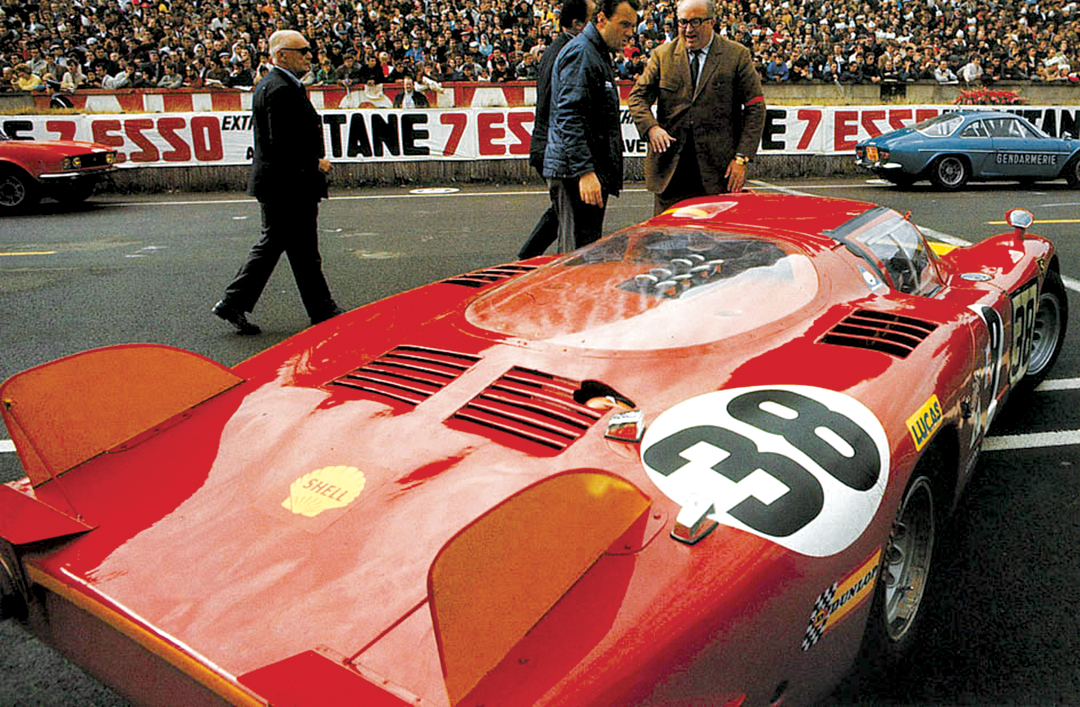

Perhaps most surprisingly, the 2-liter Alfa Romeos not only ran well up the field, mixing it with the bigger Porsches, but three of the six cars made it to the finish. Ignazio Giunti and Nanni Galli finished 4th to win the 2-liter class; Mario Casoni and Giampiero Biscaldi were 6th; and the car you see here, chassis 75033.018, was brought home 5th overall and 2nd in class. It was driven by Autodelta works drivers Spartaco Dini and Carlo Facetti. Some years later, when I developed a fair obsession for Alfa Romeo models, it was this car, with race #38, which was the very first scale Alfa model I built. Last year I managed not only to drive but also compete in the very same car, and spend some time reflecting on those days with Mario Casoni, who drove it in other races in the period. What goes around comes around.

Alfa Romeo in the 1960s

Photo: Rene

Alfa Romeo left Grand Prix racing at the end of 1951 after winning the first two World Championships for Drivers with the 158/159. The decision was made to design and build a racing sports car for the then-current sports car regulations. This resulted in the appearance of the now well-known Disco Volante, which in its original exciting-looking form with a 2-liter engine was a complete failure as a racecar, while the highly modified 6C 3000CM was constructed for long-distance races in 1953. Despite some promising performances, it managed only one victory, at the 1953 Supercortmaggiore race in open form in the hands of Juan Fangio. For 1953 Alfa Romeo departed from major participation in competition, with the exception of involvement in touring car races, where the focus was mainly on supporting amateurs. As was the practice at the time, work continued on a variety of prototypes, few of which ever raced, though they often incorporated features first tried many years before. An outstanding tradition at Alfa Romeo was to return to earlier well-designed projects and update them for current regulations or trends.

The financial conditions at Alfa Romeo, as in the past, forced the company to abandon competition and concentrate primarily on production cars to bolster the company’s lagging fortunes. The Giulietta saloons, spiders, and coupes of the mid-1950s brought considerable prosperity, and reestablished Alfa Romeo as a major manufacturer. This prosperity also funded continued development in the competition department, and in 1960 the Giulietta Sprint Zagato appeared in a short production run. The Giulia range then followed and the Giulietta SZ spawned the next generation racer, the Giulia TZ or Tubolare Zagato. On the surface it would appear that the subsequent development of this TZ or TZ1 as it has become known, the TZ2, was the immediate ancestor of the Tipo 33, especially since a car bearing the code 105.33 tested with a version of the TZ engine. However, that would be only partly accurate, and the Tipo 33 engine was not a doubled-up 4-cylinder TZ, but was inspired by a completely different engine with its roots back in the 1950s.

Photo: Peter Collins

In 1938, Orazio Satta went to work for Alfa Romeo, as did Giuseppe Busso in 1939, and they worked side by side on a huge range of innovative projects. By 1959, Satta was managing the design departments, and from 1948 to 1977, Busso had been responsible for the design of all the mechanical parts produced at Portello and then at Arese. Satta had two deputies, one of whom was Giampaolo Garcea and the other Busso. Satta, as manager, laid down the general rules and plans for the design department, and his deputies carried these out. Satta and Busso had been involved in competition work in the early and mid-1950s, experimenting with a proposed 12-cylinder Grand Prix car, the 160, which was never built. A number of prototype engines were built, including a 2-liter V-8 block to go into a sporting GT car, but it never reached production. Nevertheless, the engine blocks were made, the idea of a small V-8 being very attractive to the design engineers. I had the great good fortune to be able to examine the prototypes of these original V-8 blocks as they sat on the shelves of Marcello Gambi’s workshop in Milan. Under Satta’s leadership, Alfa Romeo produced a wonderful range of cars in the postwar period and noted Alfa historian Luigi Fusi credits Satta for providing the leadership for everything from the conversion of the Grand Prix 158 engine from single-stage to two-stage superchargers in 1946 through the Tipo 33/3 tubular frame 3-liter car of 1972.

A number of ideas from the still-born 160 were adapted when Busso was largely responsible for designing a racing prototype. This was indeed the prototype for what became the Tipo 33. A number of chassis were later passed to OSI and they eventually built a concept car known as the OSI Scarabeo, which incorporated many features Busso had been trying to capture in the prototype. The Scarabeo first appeared at the Paris show in September 1966. The 160 would have had the driver as far back in the chassis as possible, and the design centered on the driver being able to assess and control the behavior of the entire car. These principles were incorporated into the prototype and then into the Scarabeo, with the driver well back, though these two cars had the engine behind the driver, unlike the 160. The Scarabeo used a 4-cylinder Giulia engine located transversally and at a slightly inclined angle. Visibility and driver control were excellent, clutch and gearbox were integral with the engine and drive to the differential also an integral unit. A novel approach to the chassis frame was taken, with large diameter tubes linked in an H-shape, these tubes carrying the fuel.

Photo: Peter Collins

Experimentation with exotic materials was part of this project, with considerable magnesium appearing in various versions. Three of the Scarabeos were built, one of which remains in the Alfa Romeo Museum at Arese in coupe format. A spider also exists in Alfa Romeo’s possession though it is not on display, and a third car managed to escape and is believed to be in Canada. The spider version of the Scarabeo bears a strong resemblance to the prototype that Busso had been working on and it seems likely that the prototype chassis became one of the Scarabeos. The spider prototype had been tested in 1965 with a TZ engine, sometimes thought to have been in TZ2 specification. However, the prototype that was taken to Alfa’s test track at Balocco on January 14, 1966, with Consalvo Sanesi as the test driver and Giuseppe Busso in charge, had the developed V-8 unit based, to an extent, on the mid-’50s unit. The car tested again at Monza a short time later, with further engine and body developments. The prototype had the engine in-line rather than transversally as in the later OSI Scarabeo. This little effort in the depths of the Italian winter turned out to be the first running of what would become the Tipo 33 sports racing car of 1967.

The T33 Races…and Wins

The Autodelta firm run by Carlo Chiti and the Chizzola brothers had been running the competition department for Alfa Romeo for some time, and by 1967 had been successful with saloon and GT cars, notably the TZs. They ran the sports car program and had a debut success with the 1967 T33 at the Fleron hillclimb in Belgium. The new car was a striking machine, with the unique chassis frame with two side members that acted as fuel tanks. These side members were joined by a third tube that also acted as a fuel-carrying tank. The tubes were constructed from heavy-gauge aluminum and had been riveted together, and they had been given a plastic internal coating to prevent leakage. The construction of this chassis frame would be improved for 1968. The front rack and pinion steering and front suspension was carried by a magnesium subframe that formed the front bulkhead.

Photo: Peter Collins

There was independent suspension all around with wishbones and links and coil-spring damper units, with rear radius rods. The suspension at the rear was carried by another magnesium subframe consisting of two legs connected by a sheet metal support saddle. A six-speed gearbox hung at the back of the engine, and braking was by ventilated discs, the rear brakes being inboard. Thirteen-inch wheels were used and the wheelbase was measured at 7’4”.

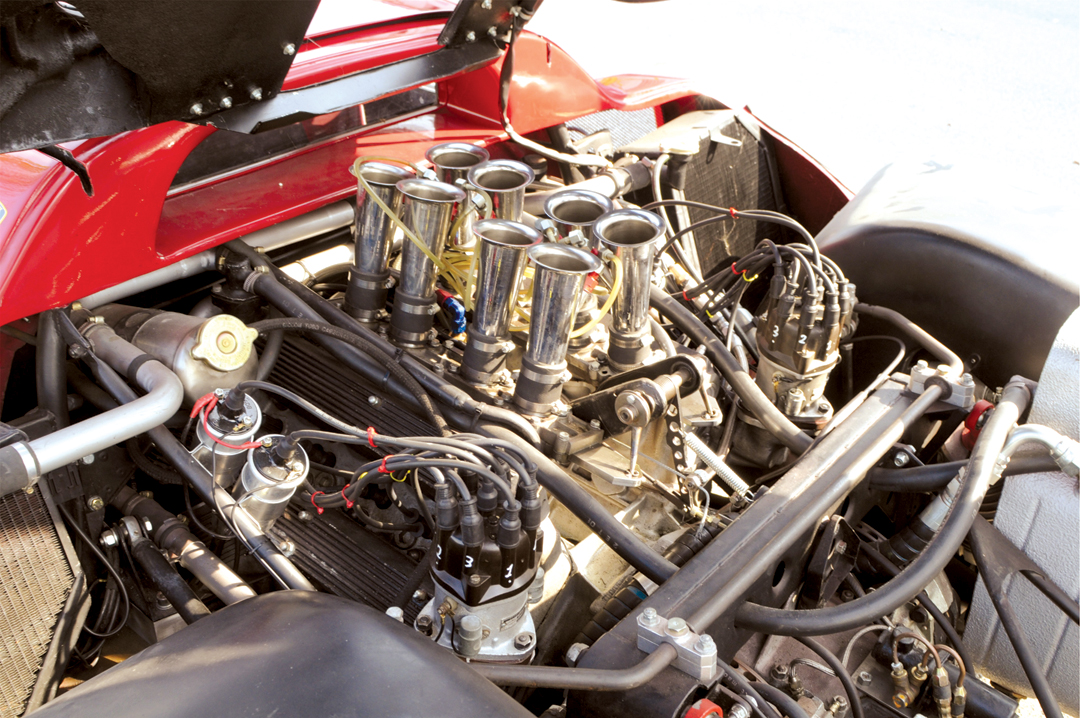

The 90-degree V-8 engine had chain-driven twin overhead camshafts on each bank, with hemispherical heads and 48-degree valve angles. Bore and stroke was 78 mm x 52.2 mm, giving a capacity of 1995-cc, and the compression ratio was 11 to 1. The kerbside weight was 580 kg, and top speed varied between short- and long-tail versions between 170 and 185 mph.

The 1967 car was by no means a big success, though it was often very quick indeed. It retired at Sebring, the Targa Florio—where there were four cars—and at most of the other races that season, though there were a few good hillclimb results. Andrea de Adamich and Ignazio Giunti then finished 1st and 2nd in the season-ending race at Vallelunga, which gave Autodelta hope for 1968.

The Birth of the “Daytona”

Photo: Archive Gasnerie

Work was going on in the last months of 1967 to prepare a “new” car for the next season. Much had been learned in the first year, but finances meant that the engine would remain essentially the same in 1968, and so would the chassis. This was a problem as the chassis was the car’s main weak point, and it tended to flex considerably. Nevertheless, suspension was totally revised, and aerodynamics were taken seriously, with a great deal of effort going into producing cars that could do well at the Daytona 24 Hours in early February.

While the body shape was the most apparent difference to the previous cars, there were many other changes. In order to change the center of gravity, much of the weight was transferred toward the center of the car. Thus, the water and oil radiators moved to each side. The problems of lift and instability in 1967 were approached by lowering the side profile and the front leading edge, generally reducing the height. Major changes to the body were aimed at making access much easier than it had been. It was thought there would be times when it was preferable to relocate the oil coolers to the front, particularly at slower circuits, so removal of the entire front body section was impractical. Improved air-cooling to the engine, brakes, and cockpit was also part of the body shape brief. Wind-tunnel testing in late 1967/early 1968 concentrated on better airflow and reduction in lift. There were some differences in drag coefficient between the long- and short-tail bodies, and it was recognized that track testing and racing was required to provide more information, but also that the long-tails would require stabilizing fins to locate downforce and to prevent “rolling” in very high-speed corners. The front suspension had also been significantly strengthened. Speeds for the car equipped with the long-tail were expected to reach just under 300 kph. Shortly before the cars were sent to Daytona, the figures released still had the engine turning out 270 bhp @9,600 rpm, and the weight was 580 kilograms. These figures were similar to the 1967 version, but this was a very different car.

Photo: Alfa Romeo

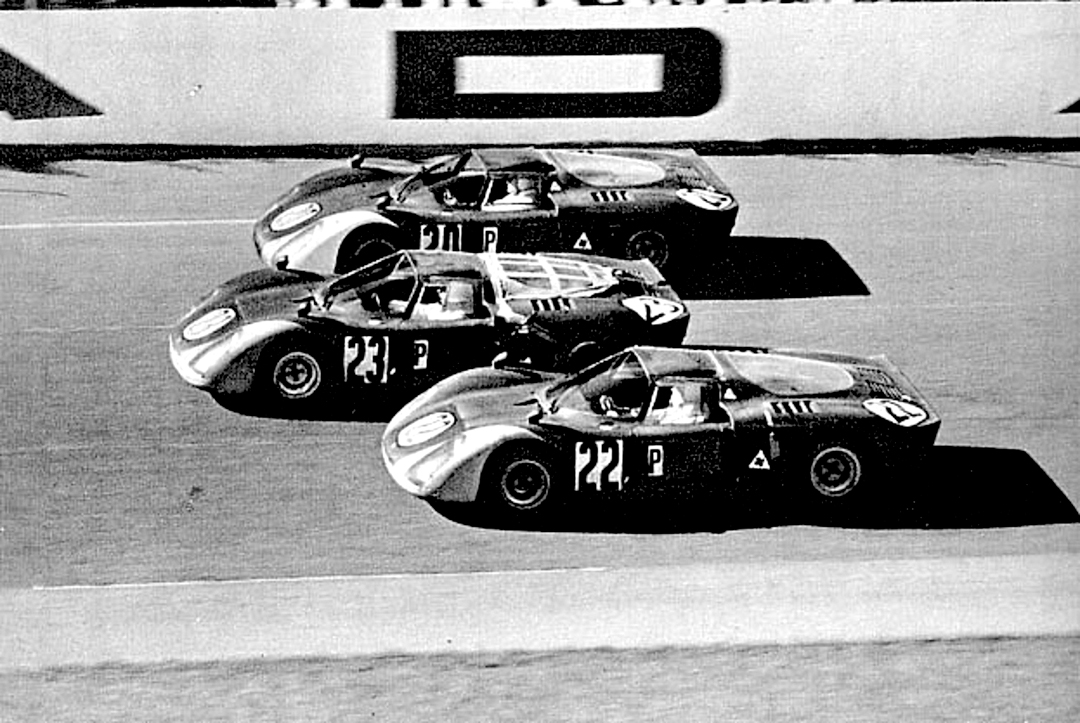

All the effort paid off. Four cars were sent to Daytona. Galli and Giunti crashed what would be their “regular” 1968 car, chassis 017, in practice and didn’t race. However, Vaccarella/Schutz, Andretti/Bianchi, and Casoni/Biscaldi brought their cars home in 5th, 6th, and 7th overall behind three works Porsche 907s and a Shelby Trans-Am Mustang. This Alfa endurance performance would ensure that the nickname Daytona would stick with these cars, though in fact body changes later on sometimes meant the same cars would be referred to as “Le Mans!” And while we are looking at the vagaries of car characteristics, can we say something cautionary about chassis numbers?

Alfa Romeo was notorious among manufacturers for not keeping good records of which chassis did which race. In addition, chassis plates on many cars were swapped regularly for ease of customs clearance so the cars matched the documents. The records on some cars are therefore fairly speculative. My colleague Peter Collins and I have spent years working on the history of these cars yet there are still many blanks. We know from existing records in the hands of Teodoro Zeccoli, and from notes from Nanni Galli and Mario Casoni, the clear identity of certain cars. We know 018 was #38 at Le Mans in 1968, and by deduction, testimony, and various other evidence that it was the Casoni/Biscaldi car at Daytona, and a few other specific races. Interestingly, Nanni Galli would make a secret mark somewhere on his car so he always knew whether he had the same chassis!

Photo: Ed McDonough Collection

After Daytona, the cars had a reasonable run at Brands Hatch, while the private Belgian VDS team, which had several cars over two years, retired at Monza. Giunti and Galli, and Casoni and Bianchi took a superb 2nd and 3rd at the Targa Florio with other T33s 5th and 6th. Vaccarella and Schutz were quick but retired in chassis 015, which was using a 2.5-liter engine for the first time. Further positive, though not earth-shattering, results came at the Nürburgring 1000, and when Teddy Pilette won two smaller races in Belgium and Holland. “Our” car, chassis 018, reappeared at Mugello in late July, where Casoni and Carlo Facetti drove, but retired, while Vaccarella/Galli/Bianchi shared the winning car, which brought considerable praise to Autodelta in Italy.

In mid-September, there was another good race for the team at the Imola 500 Kilometers. Vaccarella and Zeccoli won in chassis 029, Giunti and Galli were 2nd in 017, and Casoni and Spartaco Dini came home 3rd in 018. Then came the big race, the Le Mans 24 Hours in late September. Work was underway on a new car with a new engine and new monocoque chassis for 1969, and this took up a lot of the team’s time and finance.

Photo: Ed McDonough Collection

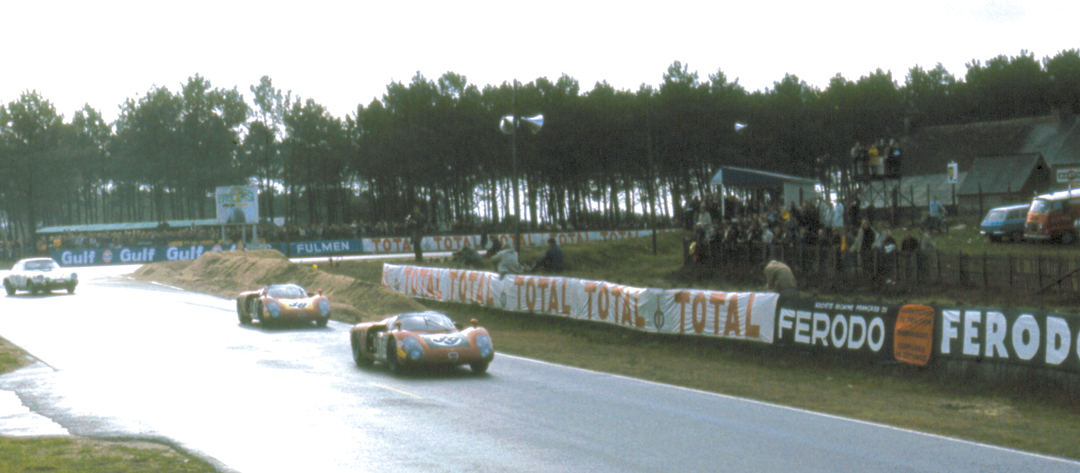

At Le Mans, however, the team was totally concentrated on doing a good job. There were four works cars and two Team VDS cars. Zeccoli and Bianchi were reserve drivers but Bianchi spent most of his time in the Gulf pit, where he had been invited to share a GT40 with Pedro Rodriguez. Good move! All the T33s ran with long “Le Mans” tails and small vertical fins. Vaccarella was quickest of the 2-liter cars and thus fastest Alfa, in 14th on the grid. Chassis 018 was 3rd of the Autodelta cars with Facetti and Dini on board.

I remember that rain came down before the 3:00 p.m. start, an hour earlier than the usual 4:00 p.m. Le Mans start. I was on the signaling crew at Mulsanne Corner, so I had the great sight of four Porsche 908s tail-sliding through the corner, with Nanni Galli all the way up to 5th ahead of the 3-liter Alpine and all the GT40s. The Autodelta T33s ran in 5th through 8th for many hours. The VDS cars retired and eventually so did Vaccarella/Baghetti. As Rodriguez/Bianchi fought off the Matra, Galli and Giunti got into 3rd spot at one stage. The GT40 finished ahead of a Porsche 907 and 908, and then came Galli/Giunti in 017, Dini/Facetti in 018, and Casoni/Biscaldi in 026. This meant that Autodelta had swept the 2-liter class, a great tribute to Carlo Chiti.

Driving a 2-Liter T33

Photo: Alfa Romeo

While Autodelta was working hard to finish their new 3-liter car, they faced numerous delays and problems, and were forced to use the older car at several events in 1969. In addition, VDS also wanted the new car so they also used the older machine until the new one was ready…which never happened for them! As 1969 progressed, the 2-liter cars were sold off and as usual, there was very poor record keeping. Chassis 018 appears not to have raced after 1969 and found its way to France and then to Japan. Both owners were going to restore it but didn’t, but eventually it came back to Italy where Marcello Gambi, an ex-Autodelta race mechanic and Alfa wizard, restored it while Signor Giordanengo from Cuneo did some work on the suspension. In the last few years, 018 passed into the hands of Pietro Silva, who works in the Republic of San Marino and is a collector of some superb competition machines. He is also an immensely friendly and generous person, and I met him through his role as an official of the organization that runs the Italian Silver Flag hillclimb not far from Piacenza.

Vintage Racecar was at the Silver Flag in 2008 when we tested the ex-Jackie Stewart Indy Lola T92 from 1967. Pietro asked if I would like a run in the T33, but it was misfiring and the gear shift selector had been bent, so we didn’t get very far. Pietro had been very helpful when our T33 book was being put together, and he invited Peter Collins and me to come to Italy again to have another run in the car on its home ground in San Marino.

Photo: Archive Gasnerie

Before we got to the car, though, there was a surprise in store. We had to stop by and visit with ex-Autodelta pilot Mario Casoni himself who would show us around his premises—where Pietro assured us he “had a few bottles of wine.” It turned out that Mario Casoni is one of the most significant wine distributors in Italy, and is also the manufacturer of one of the better known brands of Limoncello. Those few bottles turned out to be millions! After a few hours of recounting Mario’s own important race history—he drove everything—we then headed off to test the Alfa.

The hilly countryside of San Marino provided a potentially great backdrop for the test, but I discovered that we were to drive it within the confines of an “industrial estate!” This was no ordinary trading estate, however. With the lush countryside in the background, the empty road ran through a concrete canyon around a huge building. The sounds were fantastic and a few laps brought all the workers to the windows. Pietro said it wasn’t enough so it wasn’t much later that I found myself back behind the wheel at the 2009 Silver Flag hillclimb.

Photo: Attualphoto

I have often extolled the virtues of this great, 9-kilometer hill on Italian public roads. Half of it is flat-out blind, and the second half a nonstop series of tortuous bends. The road is lined with thousands of fans who come out every year to see a display of some of the best racing machinery ever produced. This year, Stirling Moss was present as a competitor and loved the atmosphere, the food, and the easygoing way in which he was treated. Maria Teresa de Filippis, that wonderful driver from the 1950s and leading light of the Ancient Pilotes, was on hand as the official starter. She brought down the Italian flag with a flourish and the “Daytona” flashed off the line amid many spectators.

I have been fortunate enough to have driven many significant Alfa Romeos, and as we are now about to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Milanese company, it is great to be able to reflect on some of this stunning machinery. I have had my hands on most of the T33 variants, but it is always the 2-liter T33 that stands out as most memorable. The bodywork—in long or short form—is beautiful. On this day we were running with the removable coupe roof panel off and the car was incredibly striking in that aesthetic way that the great cars should be. On the opening stretch the 6-speed gearbox got a workout…1-2-3-4-5-6. Through the chicanes on the straight it was 6-5-4-3-2-1 and then up again. There was still a touch of oily plug, so the revs needed to be kept up. The car flew into the midway village of Lugagnano, the crowds reacting to the blipping throttle as it sailed away to tackle the “real hill” where it was all first, second, and third for another four kilometers.

Photo: Ed McDonough Collection

The Alfa T33 made its reputation on versatility…being able to run so well at Le Mans and win on Italian hills in the same season. Here it was again, that same Le Mans car, winning on one of the great Italian mountain courses. Fantastico!

Photo: Alfa Romeo

This car is now up for sale. If you want a taste of true history, you can contact the owner through me. You won’t regret it.

Photo: Alfa Romeo