Dan Gurney is a man whose accomplishments need no introduction. In addition to winning in everything from Formula One to NASCAR, Gurney laid claim to a long and successful career as a team owner, car constructor and truly one of racing’s nicest and most approachable individuals. As a long-time friend of the magazine, VR has had numerous opportunities to speak with Dan on a variety of topics. What follows is a compilation of some of the more insightful discussions we’ve enjoyed with the legend over the past 20 years.

Gurney: Well, ya know, opera includes sound, and the sound of engines. I was never a great fan of opera, and I wasn’t into show business.

But, anyway, one of the things that does have a connection, one of my first passionate racing fan experiences was at a little track in Freeport, Long Island. It was a little one-fifth mile paved track. One end of the turn was totally flat, and the other had a little tiny bit of banking on it. Because it was paved, the cars shined, and it was nighttime racing with lights. They would bring the cars out with John Phillips Sousa’s marching music and baton twirlers like cheerleaders, then roll these midgets out to do battle. These were the days before roll cages and all of that, and these were the days when it wasn’t just one kind of engine. It was probably, on any given race, you had five different brands, different sounds. Among other things, there were huge, standing-room-only crowds, and we had a driver from our town in Manhasset named Phil Walters, who raced there as Ted Tappett. It couldn’t have been…it was like going to heaven every week when we’d go to this thing. At the end of that event, usually there was one section outside the grandstands where the motorcycles would park. So afterwards they’d fire these cycles up, everybody getting ready to leave. And, of course, they all had open exhausts and everything else, so that was an additional entrée to the racing. So the sounds of racing engines and the smells, you know, Castor Oil was used a lot in those days. Those were all…that isn’t opera, but there’s more to it. So that was it.

VR: Sounds almost like the sound more than the speed got you in the beginning.

Gurney: Yeah, it wasn’t speed so much, but there was a lot of danger involved and a lot of skill, and a lot of—without even realizing it—technology. Why does one engine sound different than the other? Why does one guy get down the straightaway a little bit better, and how come some people can work their way through traffic without hitting other people when other guys cannot? How do you choose up sides about who’s your favorite…it was all part of it.

VR: So you didn’t actually get behind the wheel yourself until you moved to Riverside, California?

Gurney: That’s right. First time behind the wheel at a race was at Torrey Pines, which was once a track and is now a golf course.

VR: In your early days, you and Skip Hudson had a very close relationship, both as friends and as racers. Can you elaborate a little bit on Skip’s impact on you and your career?

Gurney: Naturally, we met because of the hot rod element and because Skip was quite an exceptional athlete. He liked boxing, and we ended up both having some confrontations, and also ended up really good friends. I found out he wanted to become a driver, as did I. We naturally gravitated to the same sort of things. He had a series of really good looking street roadsters, and we were all in the flathead era. The Ford flathead was the engine of choice. One of the things that really did help both of our careers a lot was that we started using a stopwatch. Skip and I made a sworn oath that we would never do anything except give the exact time we actually took, regardless of who ended up being quickest or not. So we used that as a way of developing our own driving styles. We used dirt hillclimbs or dirt roads around orange groves…

VR: This is all in Riverside County. Were you basically laying your own course,?

Gurney: Yeah, so we actually could develop a style that showed up on a stopwatch. Otherwise you can talk all you want about a style or how you’d do something, or you’d be smooth and all that, but that’s all irrelevant if the stopwatch doesn’t say it’s better or worse.

VR: So you’re really one of the founding fathers of data acquisition?

Gurney: (laughter) That’s right.

VR: You were each other’s onboard computer?

Gurney: That was it. We weren’t using an hourglass! I mean you needed that insight. Otherwise you were just guessing. So that was a big element in our development. Our big problem was how do you get into an industry that doesn’t exist yet? Which is really what it was. There was quite a bit of racing, but the owners were driving the cars themselves out here. To be a young, struggling driver and to get an opportunity, I mean, there were just very few opportunities there.

On one occasion, we were invited by Tony Paravano up to Willow Springs for a test. I got fired first—for having gone off the road. Later on that day, further up the chain, Skip got fired. So we both got fired on what was then our biggest opportunity. But we persevered. That was probably 1957.

VR: I’ve talked with a number of drivers from the ’50s and ’60s—and you’ll have to pardon the question—who felt that Skip was the guy who was really going to go someplace in racing! In their eyes, he was the one who was going to go all the way. Looking back on all that now, what do you think it was that differentiated the two of you and enabled you to really take off?

Gurney: Well, luck. Luck was an important element. Skip was a much better marketer. The term “marketing” didn’t exist in those days, but Skip was very good at walking in the front door and charming the potential car owner or the guy who was going to give him the opportunity. I was much more reticent and wasn’t a great salesman. I’d say that was my biggest problem. But in terms of what you do once you’re in the car, I probably had a slight edge on Skip. Skip was very good, but in the end, how pure your desire was—or is even today—has a lot to do with success. As you get further into it, when the margins between the guys you’re up against and yourself, become smaller and smaller, you have to be able to delve down and do something about that, or else you’re pretty much stymied.

VR: Legend has it that when a brushfire threatened your home, the only personal possession that you took with you was your ’67 Spa F1 trophy. Does Spa rank as your most cherished victory?

Gurney: Well, that’s a doggoned nice trophy! I know it was commissioned by Larry Truesdale of Goodyear, who went to the silversmith who made the original trophy, which is kept at the track, and had him make a duplicate. So it is a genuine duplicate of the original one that has a lot of names of the Spa winners from before World War II up until it stopped when I ended up with it. So, yeah, that’s a very special trophy.

VR: But as far as race victories go for you, which ones stand out in your mind as having the most meaning to you either as an owner or as a driver?

Gurney: In the end, there are lots of bits that you rank in different ways as to your own assessment of how well you did and under what handicaps or lack of them. But in terms of…yeah, the Spa victory with a car which we built here in California and had our own engine that no one else had. It was one of those things that probably won’t happen again for a long time.

VR: Or ever, unfortunately.

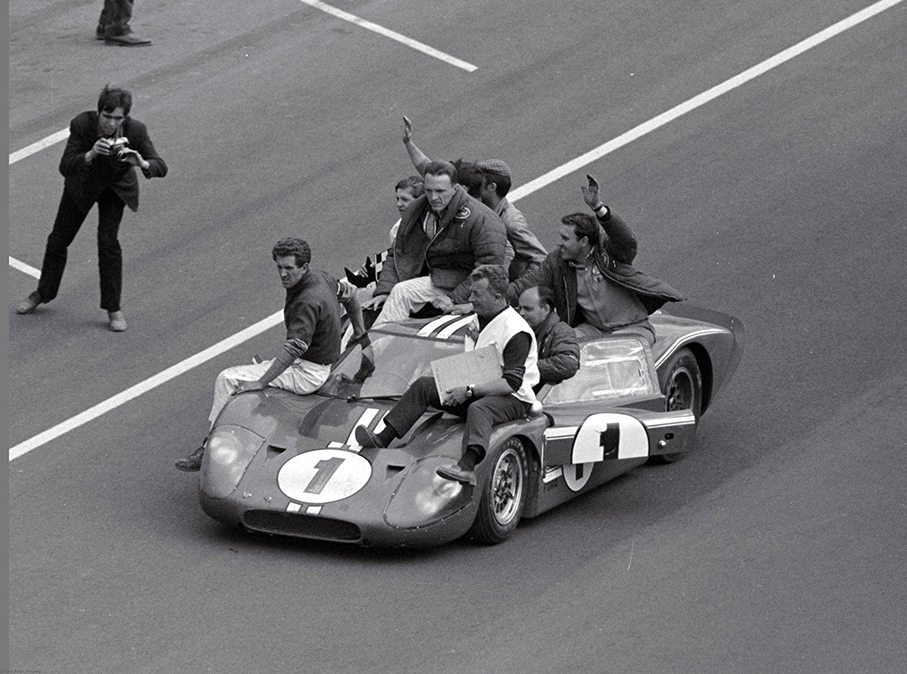

Gurney: Yeah. So that put it in perspective there. But there are others. When A.J. and I ended up winning Le Mans in that Ford victory, there was something about a watershed victory there that meant something. The first and only victory with the Porsche in Formula One was one. I won the first one for Brabham, which was very good, and also the first and only one for an Eagle.

VR: So from the mountaintop to the valley, what was the worst racecar you ever drove?

Gurney: I drove several Lotus cars that were products of being repaired… damaged cars that were diabolical. Those were not much fun. Actually, I drove an Eagle in 1970 that we had made and sold to other customers—six other customers in all. They all said, “Uh uh, this thing is no good.” I ended up having to drive it because we designed and built it. That wasn’t real good, although we managed to finish 3rd at Indy with it. It was another one of those situations where you perform by dint of just gritting your teeth.

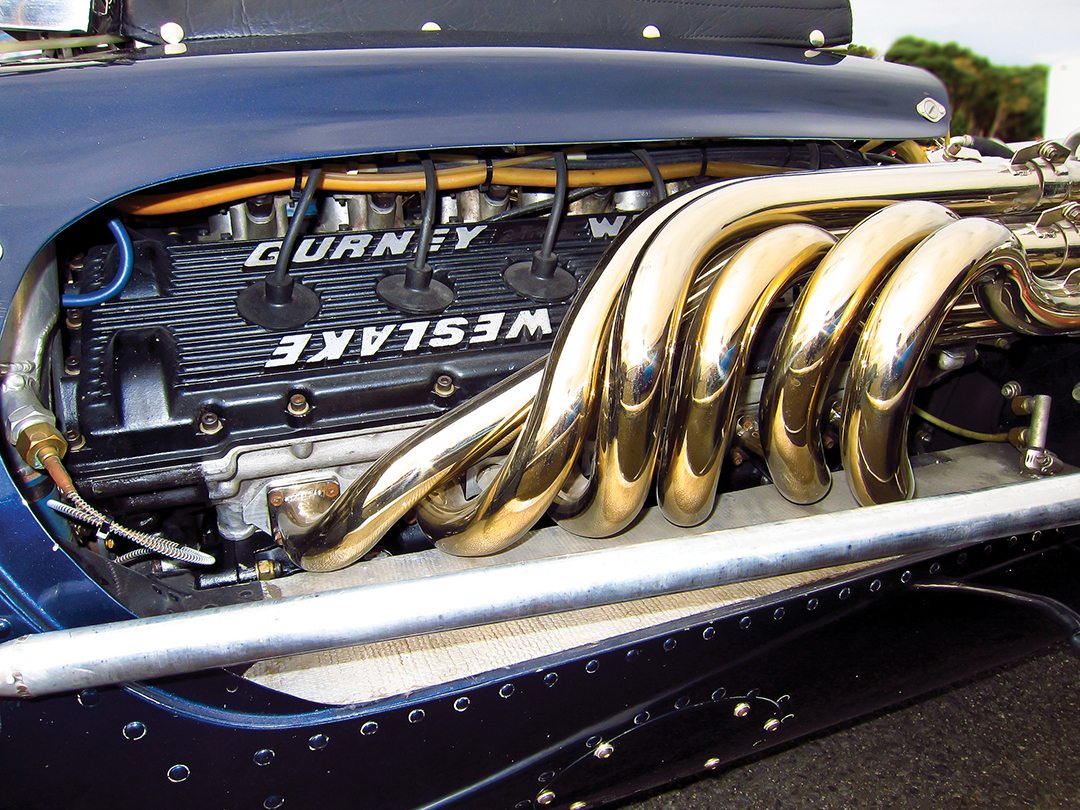

VR: Looking back at the Eagle F1 program, it seemed to be a prematurely short-lived program. Some historians have speculated that part of the problem may have been the Weslake engine and its relative lack of development. Looking back over it now, what do you think ultimately held back that program?

Gurney: One, I would say the Weslakes did an excellent job, considering the funding that we could throw at it—which was very, very slim. One of the stories that still bugs me is that our sixth race with it happened to coincide with the first coming of the Cosworth, which was funded by a budget from Ford and included getting really good machinery to do it. When in fact, what the Weslakes could afford on our program included some ex-Royal Navy World War I machinery that was pretty run down.

VR: Challenging to work with?

Gurney: Yeah, it was. Instead of using a screw to move the cutting tool, you had to do it with a hammer and then measure. But they were robust enough to make a nice piece. It certainly wasn’t a way of making interchangeable parts though! Now compare that to Cosworth, who at the time were using tape-controlled machines from Pratt & Whitney. So it was a…I mean, no use complaining about it, but I certainly wouldn’t blame the Weslakes for being a big handicap. The fact was that we tried to compete with poor precious little money. And they worked very hard, they had a lot of excellent craftsmen. More than machinery. And they had a “can-do” philosophy. Michael Daniel was Harry Weslake’s stepson, and he pushed it, and I think he deserves a lot of credit for it.

Anyway, the part that hasn’t been mentioned much is that originally that engine would have been a whole lot better because it was designed by Aubrey Woods, who was ex-BRM at the time and who had been the designer of what was a very successful 1.5-liter V8 that BRM did and won the championship for Graham Hill. But the engine I thought we were going to build was based upon a 500-cc research engine that Weslakes had run…it was a 500-cc twin, 250 per cylinder. And the Weslakes had used it in a high-speed combustion research project funded by Shell. That was what I thought we were going to use as the basis. You put 12 of those together and you’ve got a 3-liter, 12-cylinder. Somewhere in all of the shuffle, Aubrey didn’t include what at the time was a—that 500-cc twin was consistently making 76 horsepower on gasoline, which was bloody good at the time, you know, over 150 horsepower per liter. That would have made it a 450 horsepower, 3-liter. But that slipped through the cracks.

VR: So did they just decide to redesign from scratch and not use that test engine?

Gurney: Yeah, it was essentially ignored, when in fact it would have been a whole lot better. By the time I finally realized what was happening, I was really, really shaken. As it was, our engine was about the only one that gave Cosworth any real concern. And it was a very good engine. In terms of reliability it was excellent. In terms of weight it was excellent. It really didn’t have a very good oil-scavenging system. That was one of its “Achilles Heels.” All and all, the potential was very good. Although had we had the thing that was the basis of…what I thought was the basis of, it would have been pretty exceptional.

VR: At the Mosport Can-Am race in 1970 you beat Jackie Oliver in the Titanium Ti22. What do you remember of that race?”

Gurney: Jackie had the lightweight Ti22 with the 496-cid Chevrolet engine. The engine ran like nobody’s business, and it was damn hard to pass. It understeered a bit on the main straight and he lifted for a second. I got by him and it was all over. I was very proud of winning that race. I was trying hard. The team (McLaren) was hurt. Its founder, Bruce McLaren, had been killed in a testing accident that spring, and Denis Hulme had had sustained terrible burns at Indianapolis. Denis, in fact, finished 3rd in that race, burned hands and all.

VR: Regarding the death of Bruce McLaren, there are other drivers whom we also miss. What do you remember about Jim Clark, for example?”

Gurney: The best compliment I ever had came from Jimmy’s father. I was at the funeral and we were filing out of the church after the funeral. Jimmy’s father put his hand on my shoulder and said, “Are you Dan Gurney?” I said I was. He said, “Step in here, please,” and he motioned to a door off the corridor. When we were inside he said to me, “Look, you’re the only driver Jimmy ever feared.” I replied, “Mr. Clark, Jimmy never feared anything.” He replied, “Yes, he did. He feared you on the track.” I broke down and Jimmy’s sister had to console me.

VR: You have introduced a number of technical devices to racing like the wicker bill (otherwise known as the Gurney Flap. – Ed.). Can you describe any other devices which have come out of your racing experience?”

Gurney: I was one of the early ones to use the reclining (seating) position. Frank Arciero had the second Lotus 19 ever built. I went to sit in it. I didn’t fit. I said, “Come on. There’s no way. Take the seat out.” I slid down in. “Now we’ll make a seat.” Then, who walks in but Colin Chapman. His eyes zoned in. He went in and started building a F1 car. You don’t want to look like a giraffe.

VR: You retired from driving, some would say, at the peak of your abilities. You also seemed to retire somewhat earlier than your contemporaries. What was the reason for stepping away from the cockpit at that time?

Gurney: It’s very easy to give out the wrong impression, but I had done it for 15 years, and I had in more recent times experienced a loneliness at the races. Because the competitors that I had previously looked forward to running with weren’t there anymore. It was a… you know, that took a lot of the challenge out of it. I even won a race in 1970 where I didn’t feel as though it was much of an accomplishment. It was a Can-Am race.

And I thought to myself, I guess this happens sooner or later. I didn’t want to do it as just a job. I wanted to do it because I really, really was into it 100 percent. The minute there were some doubts about it and it was only 99.5 percent, why I thought, “Let’s pull back.” I mean it was…that’s another way of saying it’s doggoned dangerous, and you can see what it does to a family and that sort of thing, too.

VR: Well, I’m sure that’s a lot of the reason why you’re here today and many of your contemporaries are not.

Gurney: I knew it was going to happen sooner or later; hopefully, it turned out to be the right step!

VR: What has been more satisfying for you, your career as a driver or your career as a constructor/team owner?

Gurney: Different, different. I think as a driver you are put on a pedestal, for want of a better description. There’s a certain something about it that’s pretty doggoned interesting if you happen to do well. And yet from a technical standpoint… I mean a driver doesn’t do it without a team, but he is more or less singled out as the recipient of most of the accolades. But from the standpoint of the team achieving things… well, it more or less says, “Hey, there are some things you can do even without drivers in races.” I don’t know which is more satisfying. I think it all changes as you get older and older.

VR: Changing gears a little bit… how do you stack up the Schumachers and the Hakkinens of this racing era with the Clarks and the Ascaris of the earlier era? Do you think they’re the same—of the same caliber as the older drivers?

Gurney: That’s probably a question that requires a long, drawn out…in the end, there isn’t any way to make a fair comparison. I think there’s far more specialization today. There’s far more intimate knowledge, there’s far more…you mentioned having the stopwatches as being part of the first data gathering, and nowadays, I mean, they’ve gone so far beyond that, it’s incredible. And yet you think, at the very foundation with each guy, he’s still a human.

VR: You obviously devoted a large chunk of your career to Toyota and the development of Toyota’s GT, GTP and Champcar programs. While you’ve publicly said, “Business is business,” does the loss of your contract with Toyota kind of smack as a betrayal of trust to you?

Gurney: Well, on one hand, yes. It was unexpected, although it was hinted at. I asked on quite a few occasions, “How does Toyota go about making policies?” And the answer I got from high up was, “When we find out, we’ll let you know.” They like to be seen as a very loyal outfit and, therefore, I’ve lost some faith in that aspect of them.

You know, it’s a great big company—very powerful—and if you get into, say, a PR contest, you’re going to lose. So, I’ve lost a lot of faith in what I perceive as Toyota, after 16 years, trying really hard. You know, we did the best we could and, politically, I think, we were found wanting, I guess. So I won’t go much beyond that. In some respect I feel as though we’ve escaped.

VR: Well, it’s 2000, you’re somewhat unencumbered by your Champcar program, now. It is time to rise to the nation’s call and finally run for the presidency? You now have the time to actually make a good run at it?

Gurney: That’s another vicious arena, isn’t it!?

VR: When the whole “Gurney for President” campaign started back then, it must have been pretty gratifying to have so many people show such support for you, as a person, not just as a driver.

Gurney: Well, it was. It was started by David E. Davis at Car and Driver, and was kind of tongue in cheek. But at the time it got quite a bit of notice, and people rallied around. It’s fun to make fun of it. But running for the presidency is a serious matter, you want to be pretty well prepared, and again, it’s like so many things, it takes enormous amounts of money. And it takes a degree of passion.

VR: Finally, if a genie could grant you one racecar, what would be your choice? What would be the one car that you would love to own?

Gurney: Well, we have an ’81 Eagle, and we have a GTP Eagle. We have a GTO Celica. I have a ’68 Eagle. Those are pretty good cars. We no longer have Formula One cars. Miles Collier has the one that won the Belgium Grand Prix. I’ve always wanted to own a Norton Manx.

VR: The genie’s there for you, so whatever you want.

Gurney: I think one of those pre-war Alfas would be pretty darn nice.

VR: It’s interesting that you wouldn’t pick your own Eagle F1 car. I would have, if I had to answer for you. I would have expected that you’d want your Spa-winning car.

Gurney: Well, I did have it. So it’s up there. But I was thinking of one that would be enjoyable to drive around. I think the Alfa.

Click here to order either the printed version of this issue or a pdf download of the print version.