History is a curious thing, we tend to think of it as fixed and absolute, when in fact, like most things in life, it is dynamic, it can change. Or sometimes, like in grade school, we learn about a piece of history at a very superficial level, only to find out later (usually in college!) that this was just the simplified version and the real story in fact bears almost no resemblance at all to the generally held one. Such is the case with one of automotive history’s most interesting (and misunderstood) “what ifs,” the Corvette Italia.

Crankshaft Blues

In the 1950s, Gary Laughlin was a successful oil-drilling contractor from Fort Worth, Texas. Like friend and fellow competitor Jim Hall, Laughlin was able to earn enough from the oil fields of the world to fund his participation in SCCA sports car racing. Throughout the ’50s, Laughlin raced a wide variety of sports cars including an Allard J2X, a Lotus and a string of Ferraris, including a 166 MM, 750 Monza and a 250 Testa Rossa.

However, by late 1958 Laughlin was getting fed up with the high cost of Ferrari’s machinery. At one point in time, Laughlin broke the crankshaft on his Ferrari and after ordering a replacement for the princely sum of $350 was dumbfounded when the crankshaft made it to the States with a final price tag of $1200, after all the middleman had taken their taste—and this at a time when $1200 could buy you a new Mini Cooper and leave $400 in your pocket. Laughlin decided he’d had enough. “I think I had eight or nine Ferraris,” says Laughlin. “I finally gave up racing because I couldn’t afford a new car every year.”

But Laughlin still admired the handsome looks and performance of the cars from Modena. With business interests in several Chevrolet dealerships in Texas, Laughlin began to dream of a “hybrid” car, one that married Italian good looks with the performance and reliability of Chevy’s relatively new small-block V8. Laughlin reasoned that the Chevrolet Corvette, with its 315-hp fuel injected engine, would be the perfect platform to build his own GT car upon. The only question was where would he source the bodies?

The answer would come from his friend Pete Coltrin. At the time, Coltrin was an American journalist living in Modena, Italy. Laughlin recalls, “I knew Pete Coltrin from racing in Southern California. He was a friend of Ray Brock, Ak Miller and Don Francisco.” Coltrin, by that point in time was a Modena “insider” with good connections, including a relationship with coachbuilder Sergio Scaglietti. Coltrin connected Laughlin with Scaglietti, resulting in the Italian agreeing to take on the project.

Photo: Klemantaski Collection

A Tale of Three Texans

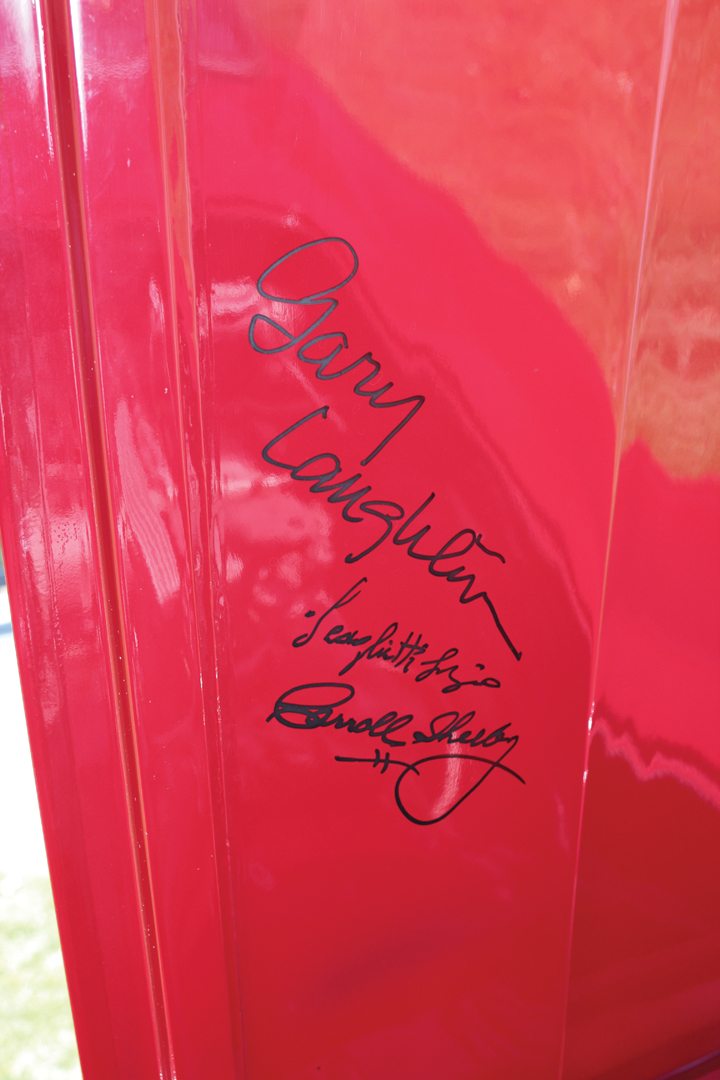

As his project began to gel, Laughlin approached two of his fellow Texan racer friends, to see if they would be interested in what amounted to an Italian-bodied Corvette. One of those friends was Jim Hall, who said he would and was willing to contribute some funds to the project. The other racer was Carroll Shelby, and it’s here where our history lesson begins to shape-shift.

In 1958, Shelby was coming to the realization that his successful racing career would soon be coming to a close. Looking to a future without racing, Shelby set his sights on becoming a constructor. Being a shrewd businessman, Shelby knew that building his own car from the ground up was a recipe for financial ruin—many a rich man had been brought to his knees chasing that windmill. Instead, Shelby saw opportunity in taking an existing, underdeveloped car and turning it into a sports car by “hot-rodding” it with a more powerful engine, such as the small-block Chevy that was being used to such great effect in cars like the Lister. As such, Laughlin’s concept sounded like an ideal solution, so he too said he’d be willing to go in on a car.

While Shelby, later in life, claimed to have pitched GM’s Ed Cole and Harley Earl on the Corvette Italia (as it latter would become known), Laughlin states that Shelby, in fact, had very little involvement in the project, “Shelby was a help in breaking the cars off the production line in St. Louis, but beyond that he had nothing to do with the cars.” Laughlin’s pitch to GM was that the Italia could be an exclusive Corvette option, offered through GM dealerships across the country.

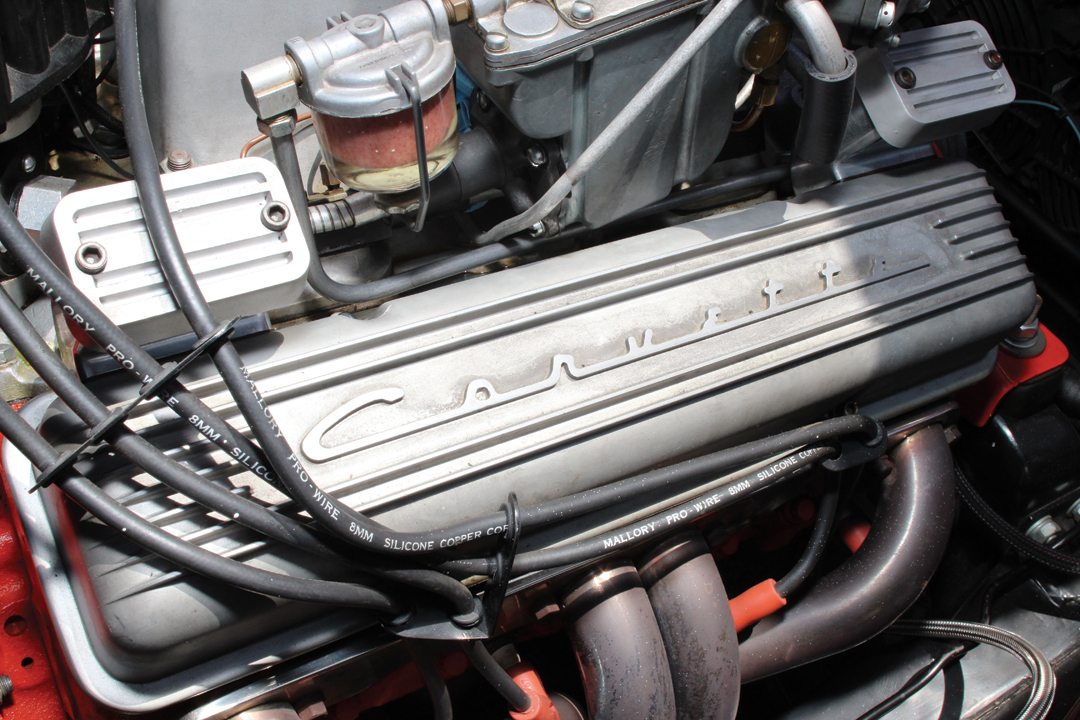

Whether Shelby was present for that pitch to GM, only Laughlin now knows, but Laughlin does acknowledge that Shelby was a help in convincing GM to sell the bare chassis. Despite Laughlin owning several Chevrolet dealerships, he was finding it hard to get GM to sell him bare Corvette chassis. Eventually, he appealed to Chevrolet’s General Manager Ed Cole, and with encouragement from Shelby, Cole agreed to sell to Laughlin one bare chassis equipped with a 315-hp Rochester fuel-injected engine and numerous competition options, as well as two chassis equipped with standard twin, 4-barrel-carbureted V8s and Powerglide automatic transmissions. Chassis were pulled from the St. Louis assembly line and shipped to Laughlin’s dealership in Grapevine, Texas, for $2,400 per chassis. From there they were forwarded on to Modena.

Machiavelli’s Corvette

Sergio Scaglietti was born on January 9, 1920, in the village of Tre Olmi, just to the northwest of Modena, Italy. Born the youngest of four sons and one daughter, Scaglietti’s childhood was one of very humble means. Despite his rural upbringing, even at a very young age, Scaglietti began making models of cars using scraps of wire and clay. At the age of 13, Scaglietti’s father passed away, resulting in young Sergio needing to enter the workforce to help support his family. As a result of his love for the automobile, Sergio took an apprenticeship with the Modena-based coachbuilder Carrozzeria Modenese.

After working for Modenese for four and a half years, Scaglietti seized the opportunity to join his older brother Gino’s repair business, which was situated not far from Scuderia Ferrari’s headquarters, in Modena. Soon thereafter, World War II intervened, but after hostilities ended, Sergio returned to his brother’s business for several more years.

Eventually, in 1951 at the age of 30, Scaglietti decided to venture out on his own, opening his Carrozzeria Scaglietti a stone’s throw from Ferrari’s factory in Modena. Two years later, in 1953, Scaglietti took in an accident-damaged Ferrari 166 MM belonging to racer Alberico Cacciari. According to Scaglietti, this particular repair job would forever alter the arc of his life.

Scaglietti not only repaired the badly damaged Ferrari, but in the process made a number of subtle modifications to the body to give it, what he thought were more flowing lines. Cacciari was so impressed with Scaglietti’s improvements that he drove the car over to Ferrari and showed it to the Commendatore himself. Much to his surprise and perhaps concern, Scaglietti was soon summoned to Enzo Ferrari’s office. Fortunately, when he presented himself to Ferrari, Enzo offered him a contract to construct the bodies for his new 500 Mondial sports racer (see Vintage Racecar, August 2013) that was to be offered in 1954. Thus began Scaglietti’s association with Ferrari, cementing the foundation of his now growing carrozzeria.

Four years later, Scaglietti was approached by American journalist Pete Coltrin about whether he’d be interested in taking on a project for a fellow American who wished to have aluminum GT bodies built upon a Corvette rolling chassis. Scaglietti was already constructing a GT body for Ferrari’s 250 GT “Tour de France,” and since each body was essentially hand made by hammer-forming panels over bags of sand, it wouldn’t be terribly difficult to create a variation that would fit the Corvette, which was wider in the rear, but shared the Ferrari’s 102-inch wheelbase. Plus, with the potential of the project turning into a production run backed by GM, it could prove to be a lucrative program, long term.

Scaglietti received the three rolling chassis and began work on the “prototype” car, which was the chassis equipped with the fuel-injected engine and competition options. At some point in time during the ensuing months, however, the landscape at Scaglietti’s underwent a groundswell change. Between building bodies for many of Ferrari’s racecars and production of roadcars like the Tour de France, the California Spider and his work on Laughlin’s Corvette project, Scaglietti was in need of expanding his growing operation. Perhaps seeing an opportunity to gain a modicum of control over one of his key suppliers, Enzo Ferrari not only approached his banker with the prospect of extending Carrozzeria Scaglietti a loan to expand his operation, the Commendatore co-signed the loan, as well. For all intents and purposes, by 1959, Enzo Ferrari and Sergio Scaglietti became business partners.

Perhaps as a result of their tightening business relationship, it may not come as a shock that Laughlin’s Corvette program became a back-burner project. In fact, some have suggested that Enzo Ferrari may not have been enamored with the idea of Scaglietti helping to build a “low cost” Tour de France that might be sold by General Motors in the U.S. Whatever the reason, work on the Corvette proceeded at an agonizingly slow pace.

According to Laughlin, “Pete Coltrin kept track of Scaglietti for me. I never saw the cars but once while they were under construction. I was sick of the project by that time.”

Laughlin was not the only one getting cold feet about the re-bodied Corvettes. The upper brass at GM were also having a change of heart. According to Carroll Shelby, “I was living in Italy at the time—the cars were at Scaglietti about three-quarters done by then—when I got a call from Ed Cole at 2 a.m. saying forget the whole thing. He had got his ass chewed out by GM management and been told to drop the project.”

According to Laughlin, there was concern that the lightweight Scaglietti Corvettes might undermine GM’s sales of production Corvettes. So, with no support on the U.S. side from GM and now decreasing to no support in Italy from Scaglietti, the Italia project became a lame duck that everyone just wanted to get off their plate.

It took Scaglietti over 18 months to finish Laughlin’s fuel injected prototype and ship it back to Texas, in the Fall of 1960. By the time Laughlin received it, he was disappointed with the build quality and was anxious to move on to other endeavors. Laughlin made the car available to Road & Track, which included a glowing two-page write-up in its March 1961 issue and then featured it on the cover of their sister publication Car Life that June. Soon thereafter, Laughlin was made an offer on the car and gladly washed his hands of it. When asked recently about the project, Laughlin commented, “In retrospect they were pretty junkers.”

Some time after the first car was delivered, Scaglietti hastily completed the other cars with carburetion and automatic transmissions. The second chassis was delivered to Jim Hall, who held on to his car for many years, though he too was under-impressed with the results. “I thought it was something we could make money on,” said Hall. “I know mine came with a broken windshield because it was very difficult to replace. Nice looking cars, but I don’t think I ever drove it.”

As for the final chassis (the one seen on these pages) that car was slated for Carroll Shelby. But with the Italia’s long-term prospects essentially dead, Shelby had no interest in taking delivery of the car. According to Laughlin, “He was to originally get one, but he never paid me.” Though he had washed his hands of the Corvette Italia project, Shelby had not abandoned the concept of building a European-style sports car with American V8 power. With the door clearly closed with his first choice GM, Shelby approached cross-town rival Ford with the same concept, only now marrying the underpowered AC Ace sports car, with Ford’s new small-block V8. Eager to dig into Chevrolet’s market share with the Corvette, Ford agreed. From the ashes of the Italia, it could be said the Cobra was born.

Italias on the Move

Laughlin’s prototype chassis moved around before being bought by a British collector, who sent the car to Paul Russell & Company, in 2007, to be restored and properly sorted out. Jim Hall quietly held on to his Italia for decades (eventually selling it to a collector in France in 1990), while the third chassis passed through a succession of American owners who along the way replaced the carbureted engine with a proper 283-cu.in Rochester fuel-injected power plant and 4-speed T-10 transmission. By 1990, the car came under the ownership of Barry Watkins, who restored the Italia and in 1993 sold it to Mike McCafferty. McCafferty enjoyed the car for a decade before putting it up for auction at Barrett-Jackson’s 2000 Scottsdale sale, where it was purchased by Robert Petersen, for Southern California’s Petersen Musuem, where it resides today.

Behind the Wheel

The Scaglietti Vette pulls into the parking lot perched atop the back of a flat-bed truck. As a permanent part of the Petersen Automotive Musuem’s collection, the Corvette is always trucked to shows and appearances. Other than occasionally being driven onto the lawn, the Scaglietti Vette is almost never driven. In fact, I’m honored to be the first person, inside or outside of the museum, to get the opportunity to appreciably drive the car. A trust that weights somewhat heavy on my shoulders as the reputedly $1 million Corvette is gently eased off the back of the truck and onto the hot tarmac.

Looking over the car, it’s not difficult to see the striking resemblance between this and the Ferrari 250 GT Tour de France. The separated at birth similarity is most noticeable in the car’s silhouette and especially in the “greenhouse” above the door and fender line. Yet, there is just a touch of dissonance to this familiar image, as Scaglietti had to “resize” the basic Tour de France package to fit upon the Corvette’s wider chassis. As a result the Italia varies in several subtle ways including the length and curve of the front fenders and most noticeably, the elegantly curved and sculpted “finlets” that cap the rear fenderlines and help mask the car’s wider rear track. And, of course, with Laughlin’s request to incorporate the stock grill (at least on the prototype car) the nose is subtly different as well.

Pressing the button on the Ferrari-style handle releases the lightweight and delicate aluminum door. The view inside the cockpit is of two tan bucket seats perched atop a large flat floorpan covered in tan carpeting. While any driver has to duck their head a bit to climb inside, it is surprisingly easy to get into the seats and behind the wheel, helped by the inclusion of a smaller Nardi steering wheel than found on the prototype. Once nestled inside the comfortable driver seat, it’s a revelation to experience how much legroom the Italia affords its occupants. Built for “Texas-sized” men, the Scaglietti Vette has enough legroom to accommodate nearly any driver up to and including an NBA starting forward. Like its Ferrari sibling, the greenhouse of this car is fairly low, which somewhat limits the sight lines over the dash and out of the car. The dash itself is a simple black affair with a driver-side binnacle housing a relatively small Smiths tach, speedo and fuel gauge, while a separate panel in front of the passenger houses the standard trio of water temperature, oil pressure and ohmmeter. Interestingly, the dashboard layout on this car, the third and last car built, is very different from the one on the first car built for Laughlin. Perhaps due to the fact that this example and the second came to this country unfinished, the driver binnacle looks almost barren, with just the three small gauges, whereas the prototype saw all six gauges occupying the same space.

After carefully closing the door—its lightness giving it an air of fragility—I grab the key, give it a part turn, push it in and then turn it some more. After just a moment of cranking the fuel injected V8 purrs to life, like a satiated big cat. The clutch is heavy, as I push it toward the firewall with my left foot, but not nearly as heavy as the shifter. The action on the 4-speed shifter is remarkably heavy and solid, there’s absolutely no slop or play in the linkage at all, but the effort required seems akin to changing gears on the HMS Queen Mary—heavy, but positive.

Once rolling the Italia has great acceleration as the 315-hp Fuelie is now pushing a car some 400-lb lighter than a standard Corvette. Steering is heavy at low speeds, but is surprisingly tight and accurate for a worm and ball box. As the speeds pick up, the Scaglietti Vette begins to demonstrate the unintended byproduct of its lightweight aluminum body—the handling starts to get jumpy. While Scaglietti’s shapely body dramatically improved the car’s power-to-weight ratio, the lack of 400-lbs had not been taken into account, when it came to the car’s suspension, which is bone stock 1960 Corvette. As a result, the Italia is over-sprung and has a tendency to get skittish as speeds increase or the road roughens. This phenomenon may also be exacerbated by the car’s strangely tall ride height and rock hard vintage tires. It’s both interesting and sad to note that these same issues are among some of the reasons that Laughlin became disillusioned with the car, shortly after taking delivery. While these quirks would appear to have been fairly easy problems to engineer and overcome, they were never tackled as Laughlin sold the car and moved on to other endeavors. Over the following years, this example moved from owner to owner, as something of a beautiful oddity that was never driven much and never received the type of mechanical sorting that would have addressed a number of these issues. In the case of the prototype, after receiving extensive work by Paul Russell & Company, it is reported to now be a delightful car to drive. As I spend more time behind the wheel of this Italia, it becomes clearer that while cosmetically and mechanically maintained, this Italia needs the same level of sorting in order to make it live up to its originally intended potential. And what potential there is and was!

Had any number of factors gone a different direction—GM’s support, Scaglietti’s attention, Laughlin’s persistence—the Corvette Italia could have written a very different chapter for itself. Had the project progressed and had GM embraced the program, it’s quite possible that the car you see on these pages would have become the “Cobra” of the 1960s.

And yet, its ultimate destiny was to become another missed—misunderstood— fork in the road of automotive history.

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis:Steel, ladder frame

Body: Aluminum, by Carrozzeria Scaglietti

Wheelbase: 102 inches

Track: (F) 57 inches, (R)59 inches

Weight: 2600 pounds

Steering: Recirculating Ball

Engine: Cast Iron, OHV V8

Displacement: 283-cubic inches

Bore x Stroke: 3.87 inches x 3.0 inches

Induction: Rochester Fuel Injection

Power: 315-hp @ 6200 rpm

Torque: 295-lb-ft @ 4700 rpm

Transmission: All-synchro 4-speed, reverse

Brakes: Drum, all around

Wheels: 15 x 5 Borrani wire