Out of the shadows of World War II and its aftermath has come an unique Alfa Romeo sports car flaunting stunning design and engineering. It also reveals secrets that contributed to the design of Enzo Ferrari’s post-war V-12.

Among the many pleasures of Alfa Romeo’s 111th-year celebrations is the surprise unveiling of a magnificent 12-cylinder road and racing prototype. Alfa was a lusty youngster of 31 years when it built an unique sample of a car that could have carried it to racing successes had war not intervened. But traces of its engine design remain visible in the V-12 powerplants that brought Enzo Ferrari post-war glory.

In 1938, Alfa’s chief Ugo Gobbato commissioned Spanish engineer Wifredo Ricart to build ultra-exotic, sports racing and Grand Prix designs. Gobbato also needed someone to attend to his Milan company’s production cars. Vittorio Jano had decamped to Lancia, so a crucial position was open. For this task he chose Bruno Trevisan, a reserve major in Italy’s Air Force. In the words of Enzo Ferrari, “Trevisan was the son of Gobbato’s professor when he was studying in Vicenza at the Institute for industrial experts, before graduating in engineering.”

Initially an engine expert at Fiat, Trevisan moved to Alfa Romeo in October 1934. His first task was to design a new V-12 racing engine to install in Jano’s chassis. He did a commendable job with a supercharged 12 that ultimately reached 4½ liters and 430 horsepower and won races for Alfa. Next he turned to the freshening of Alfa’s staple 6C 2300 B. He gave it a synchronized transmission and, in 1939, further updated the model as the 6C 2500.

In 1938, Trevisan’s team was engaged in designing the cars that would represent the future of Alfa. Two categories were covered. One, the Tipo S 10, was the 3½-liter premium entry with a 12-cylinder engine and 128-inch wheelbase. The other, the Tipo S 11, suited the more mainstream 2½-liter category with a V-8 engine on a 112-inch wheelbase. Both would have the fashionable integral body/frame construction and all-independent suspension. Sports versions would also be produced, including twin-cam cylinder heads for both engines.

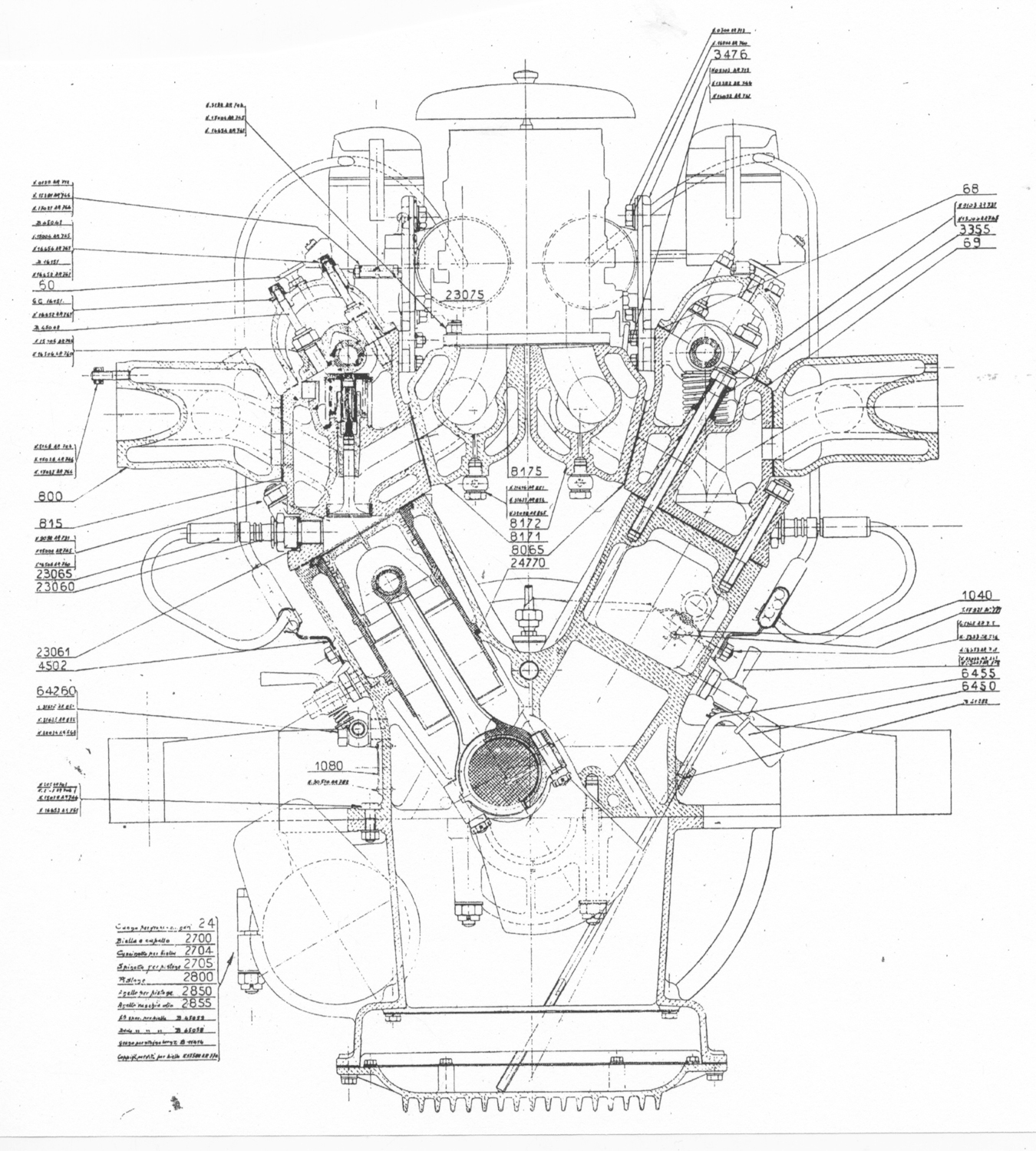

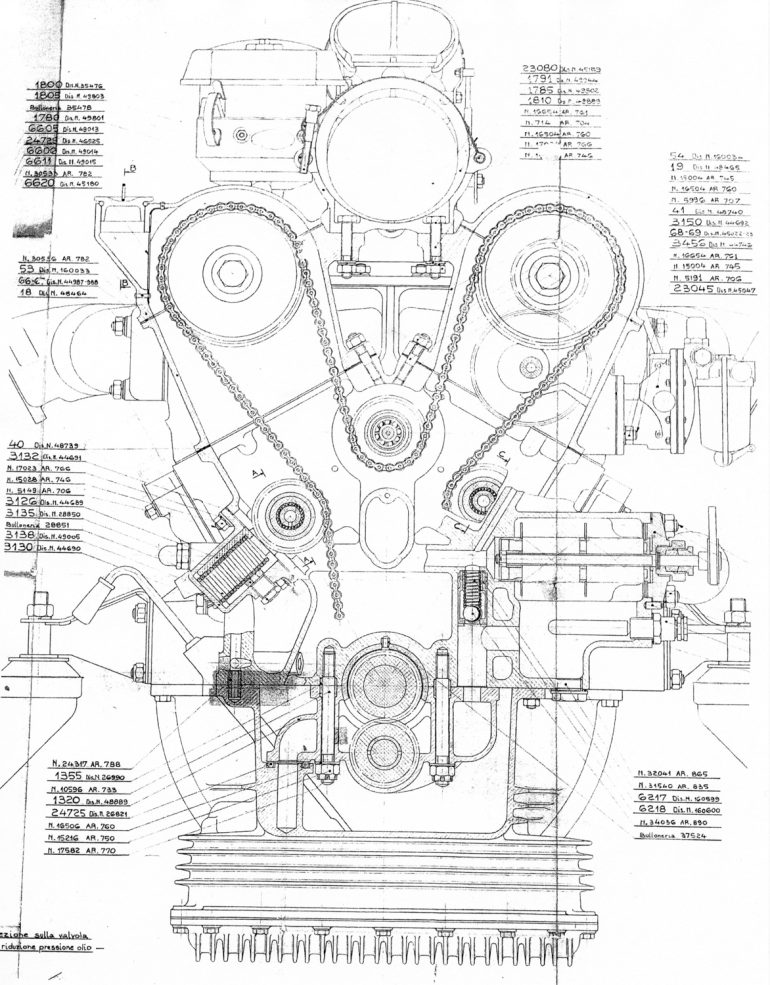

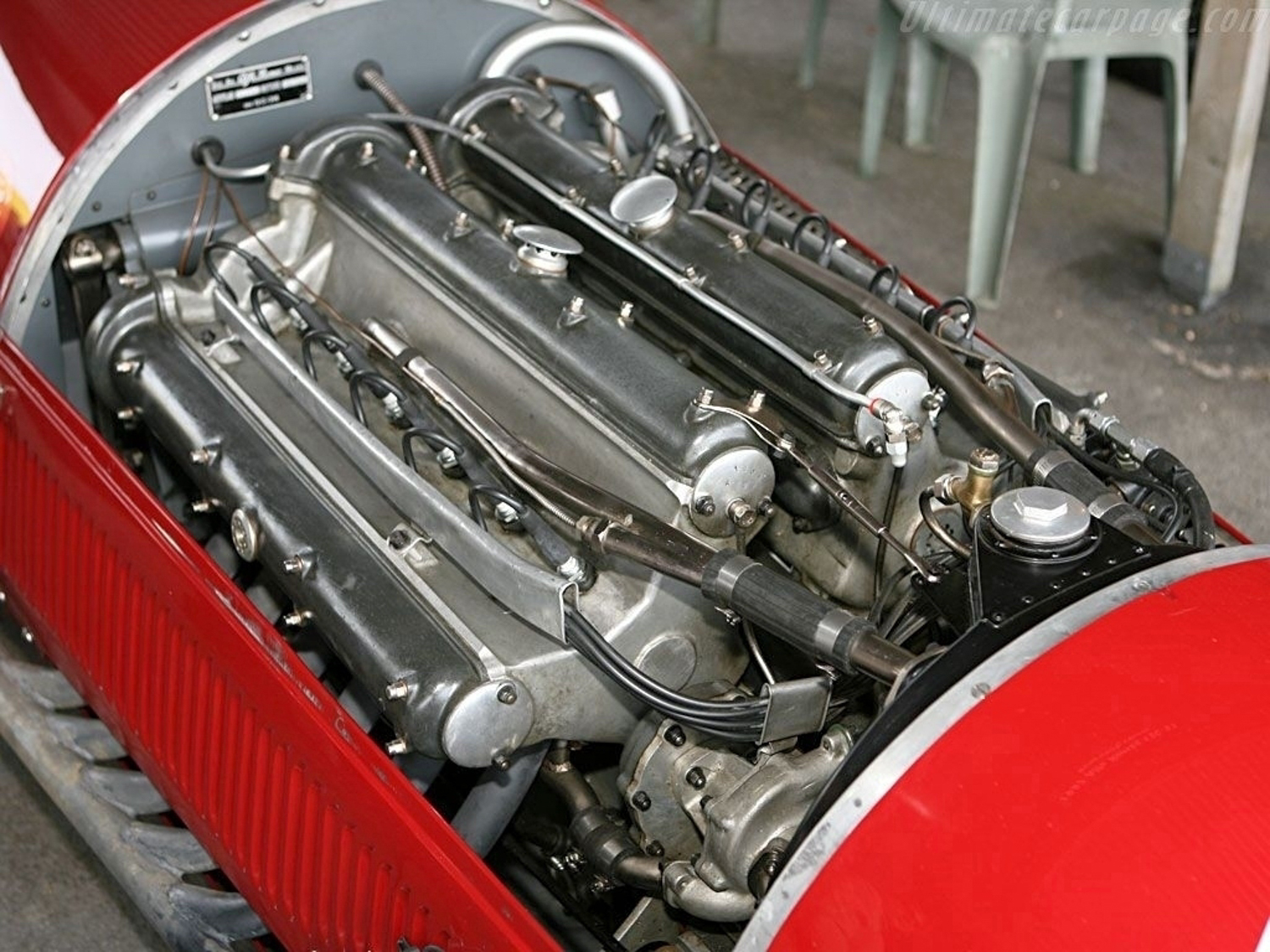

At the heart of these ambitious new models were their all-new engines by Trevisan. Although differing in their vee angles, 90º for the V-8 and 60º for the V-12, they shared a 68-mm cylinder bore, which permitted identical wet sleeves for both. All valves for both were 30-mm in diameter with the same Jano-type tappets. Valve inclination from the vertical, opened by single overhead cams, was 30 degrees from the cylinder centerline.

Along their inboard inlet faces the cylinder heads of both engines leaned toward the engine’s center at 15 degrees. Hence the same set of machine tools could be used to make the main operations on the cylinder heads of both. For both engines, Trevisan also designed twin-cam heads, using the same Jano-influenced, wide vee angle for their valves that he gave his Grand Prix engine.

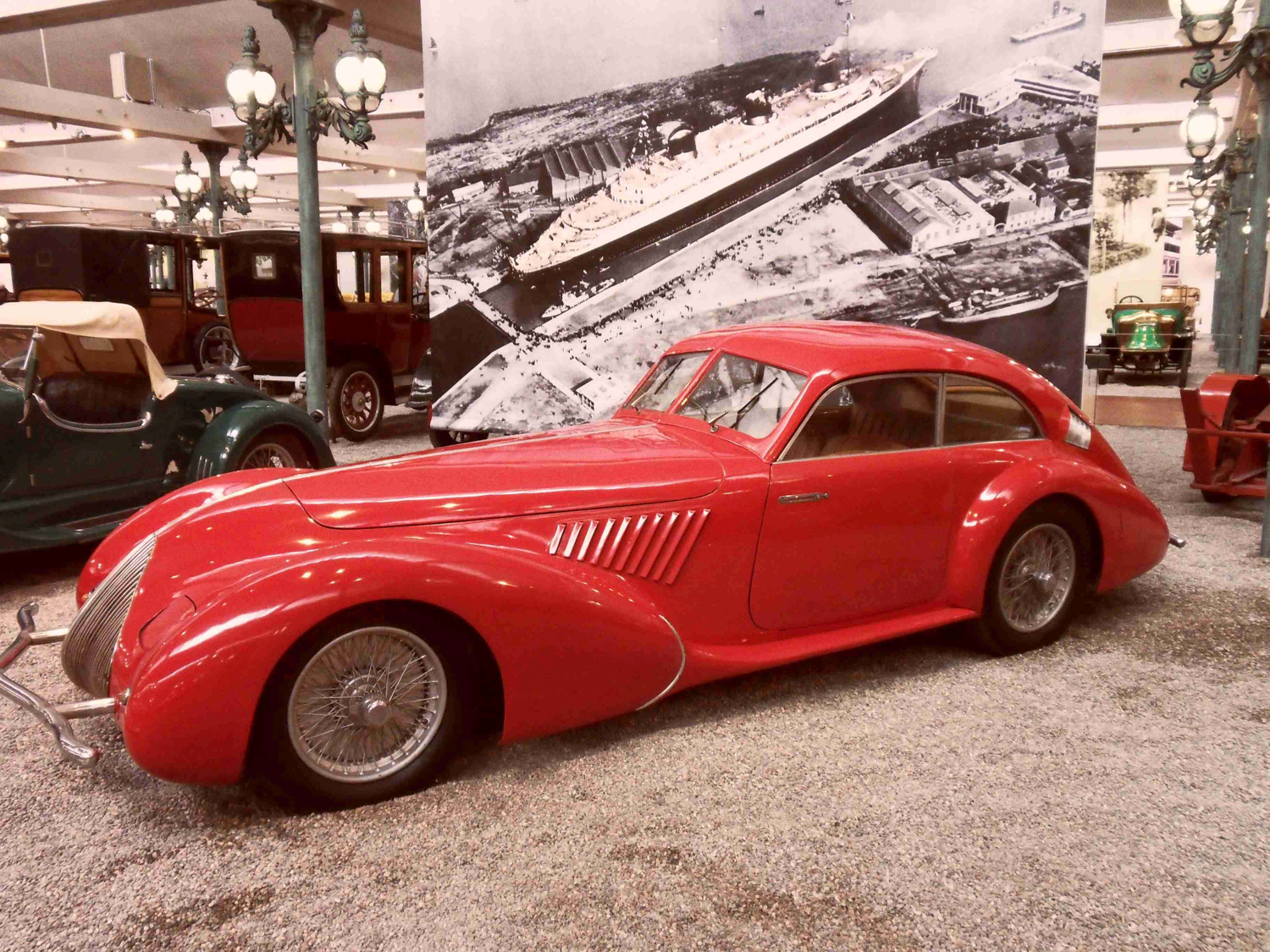

Surviving illustrations show the standard coachwork for each model with sober styling in accord with mainstream Alfa tradition. Mocked up for a sports version of the V-12 version— the S 10 SS—was a coupe with leaf-sprung live rear axle. The four-camshaft version of its engine, of which two were completed, would contribute 165 bhp at 4,700 rpm, up from the standard 140 at the same speed. It was hoped to have three such sports racers for the 1941 Mille Miglia but none was ready for a race that was never run.

In May of 1941, came “an event of considerable importance in Alfa,” wrote Alfa engineer Giuseppe Busso. “Something from Jano’s period had survived: the prototypes of two large cars. They were at an advanced stage of design and construction, the S 10 with a 12-cylinder vee engine, 3,560-cc displacement and the S 11 with an eight veed cylinders of 2,260-cc. Their first studies dated back to the years around 1935.

“At a certain point,” continued Busso, “Ugo Gobbato, the sworn enemy not only of indefinite situations but also of long periods without results, must have deemed a radical intervention necessary for a clearer, better-defined approach. It was 31 May 1941 when he sent his personal communication to the various internal bodies. It was certainly historic not only for its instructions but also, in my opinion, for the almost brutal attitude with which Gobbato expressed himself.”

The end of the road for the Bruno Trevisan creations was indeed emphatically defined on May 31, 1941, by a terse memo from Gobbato requiring that “arrangements that all work relating to these cars be suspended.” The V-8 had progressed the farthest with two prototype automobiles completed and “tested with good success” according to engineer-historian Luigi Fusi. Trevisan’s V-12s had also been brought to life, with both the single-cam and twin-cam heads, but not installed in a chassis.

Ugo Gobbato now turned to Wifredo Ricart for technical oversight of all work in progress. Engineer Giuseppe Busso, who arrived at Portello on January 1, 1939, said that “in April 1940 Ricart received a circular from the management giving official confirmation of the functions that he had been carrying out for some time: supervising both our Special Studies Service and all other design and experimentation for cars, trucks, aircraft, bodywork, racing, etc.” Ricart remained with Alfa Romeo to the expiration of his contract on March 31, 1945.

Moving his team to the northwest, away from the bombing of Milan, Ricart started work on an elaborate aero engine and a new passenger car, the Gazzella. With Gobbato’s approval, he also relaunched work on sporting cars by a Reparto Sperimentale or Experimental Department in which Gioachino Colombo was a leading designer.

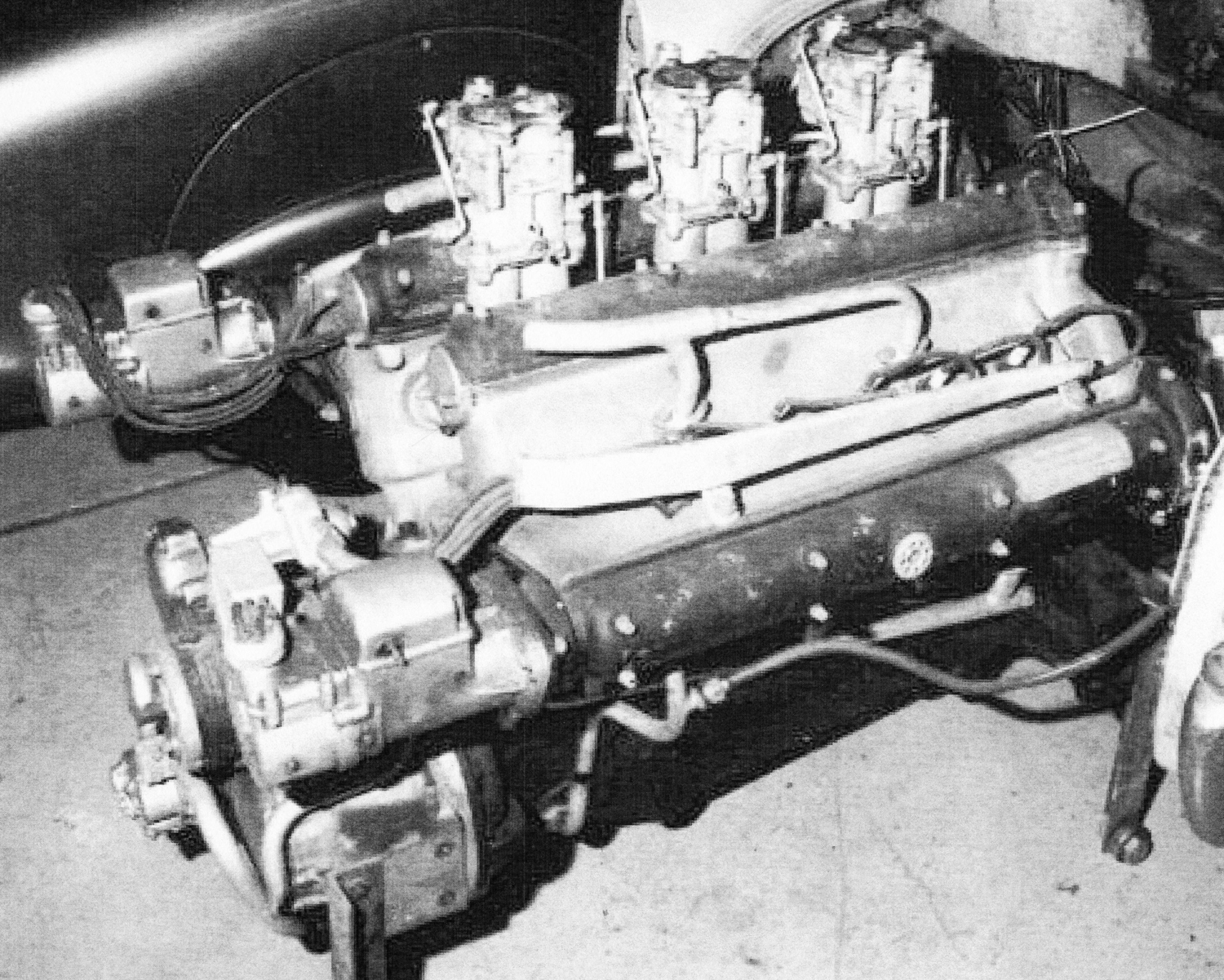

This department nurtured sporting models dating from 1939, such as the 6C 2500 Super Sport. Taking advantage of the materials created by Bruno Trevisan, under Colombo’s guidance it created more ambitious competition cars with modified V-12 engines including single-cam versions with triple carburetion.

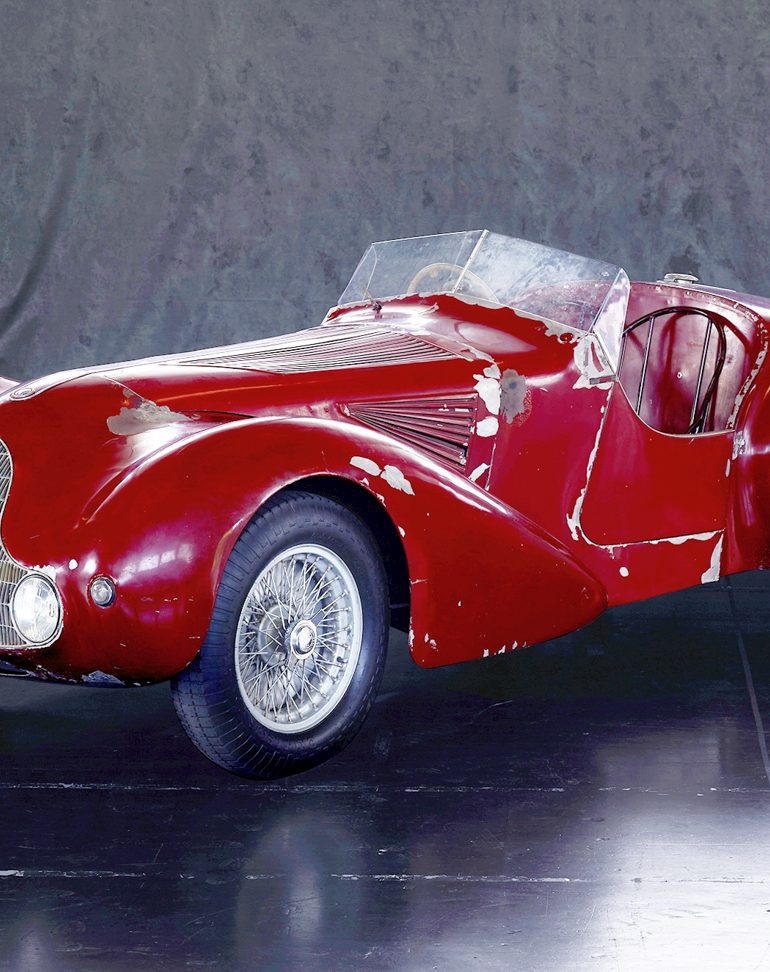

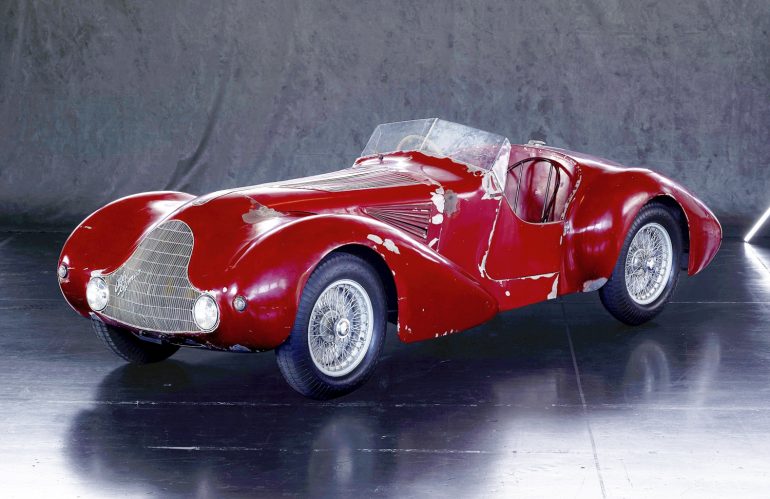

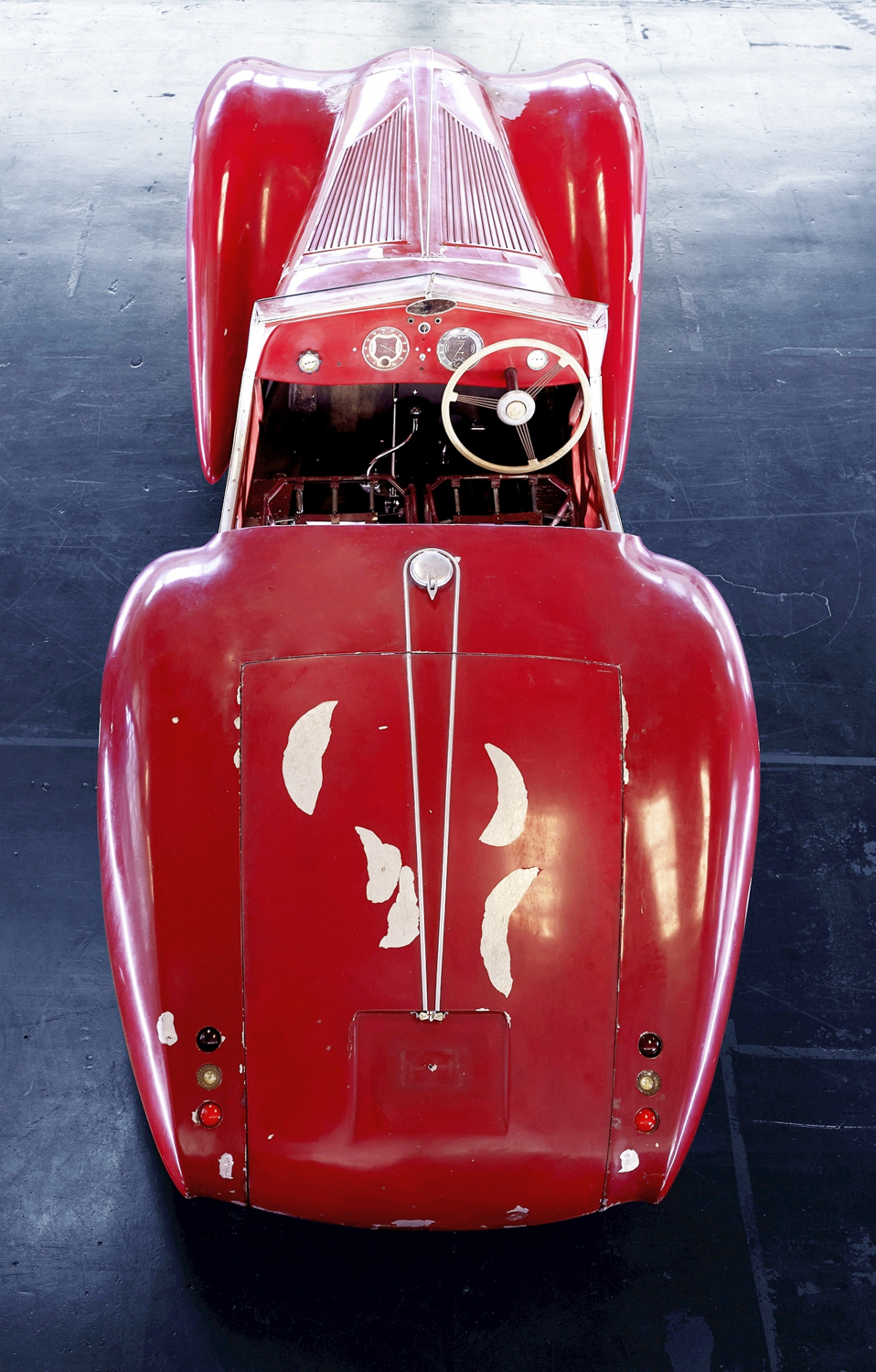

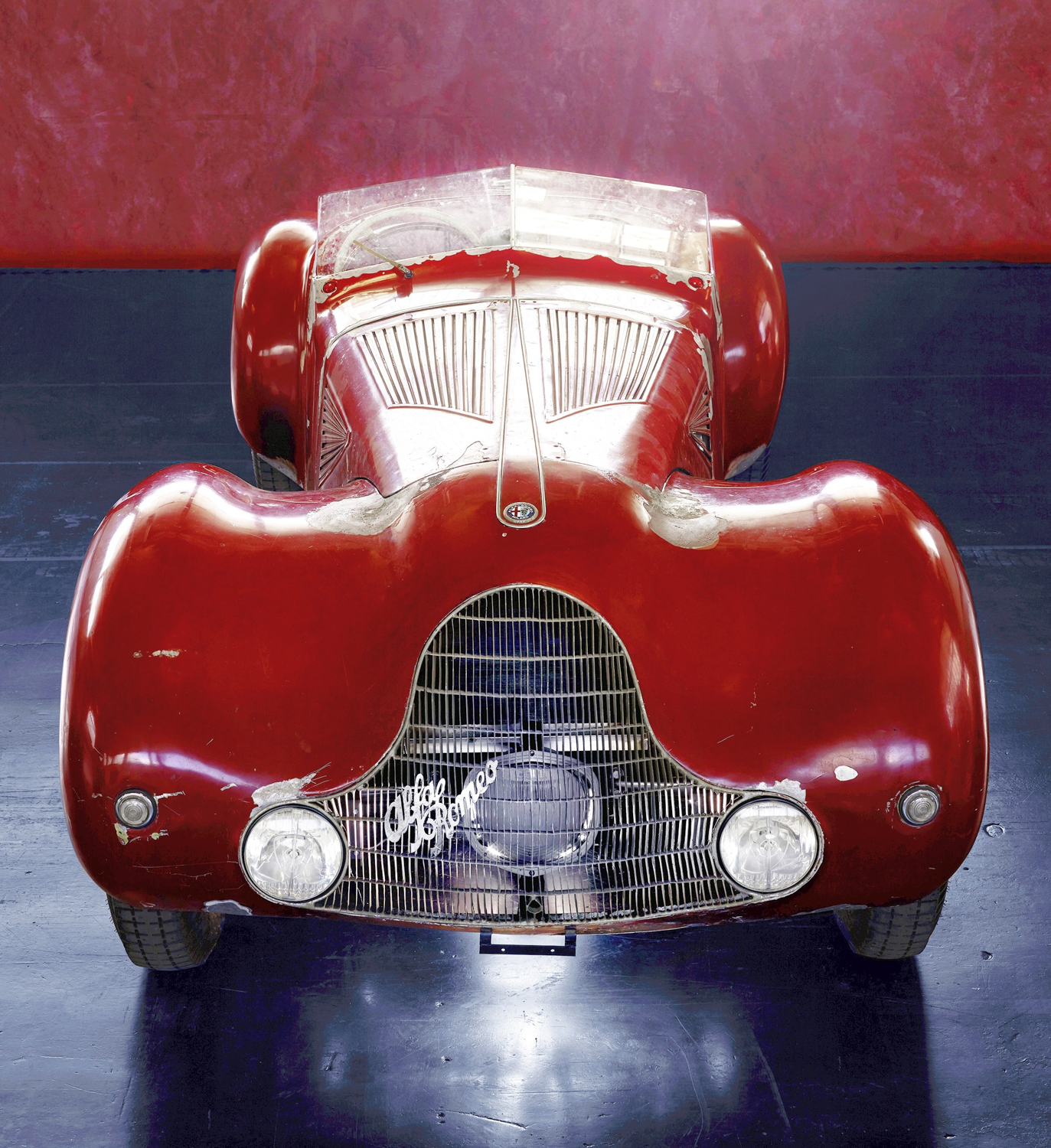

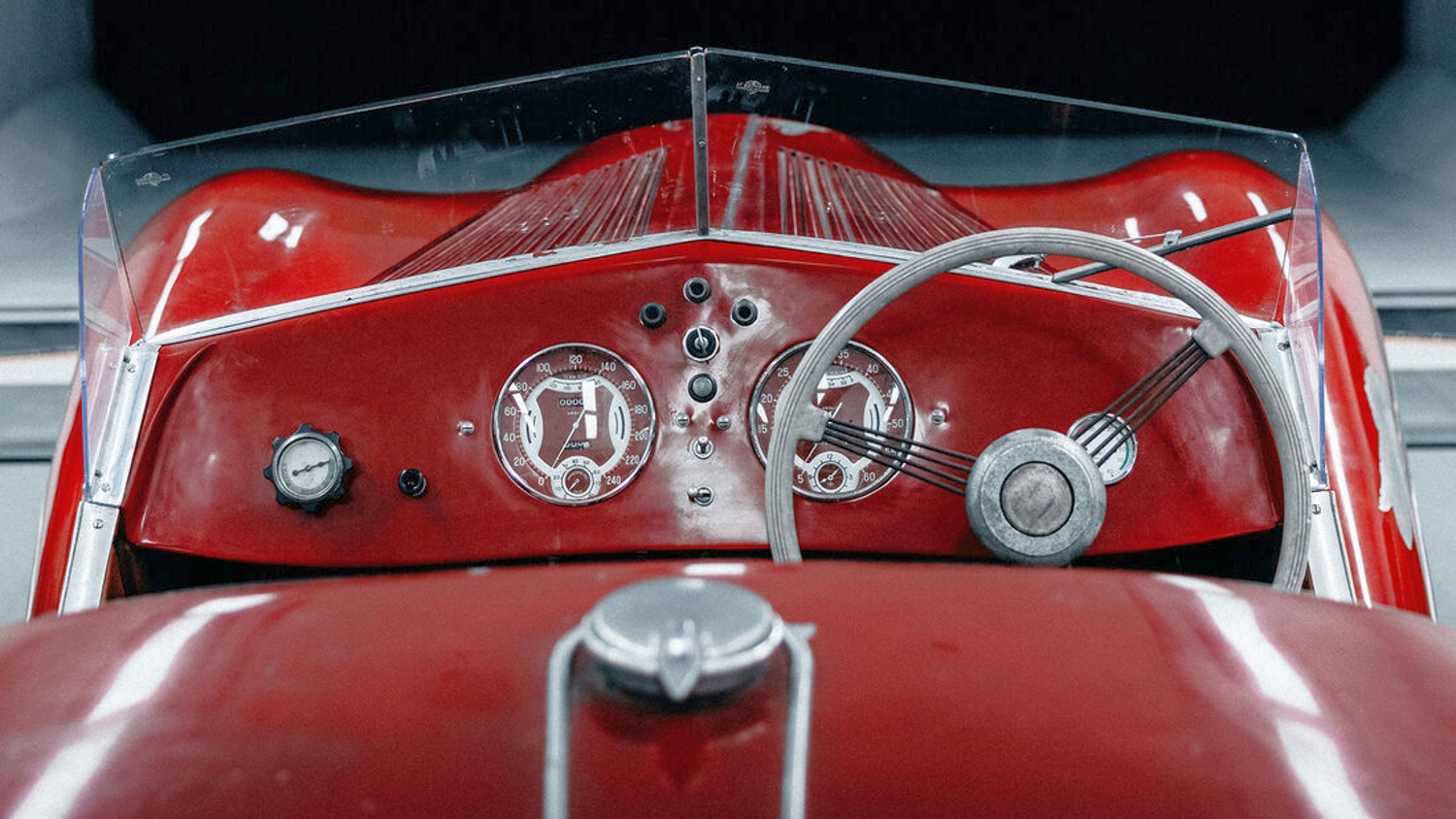

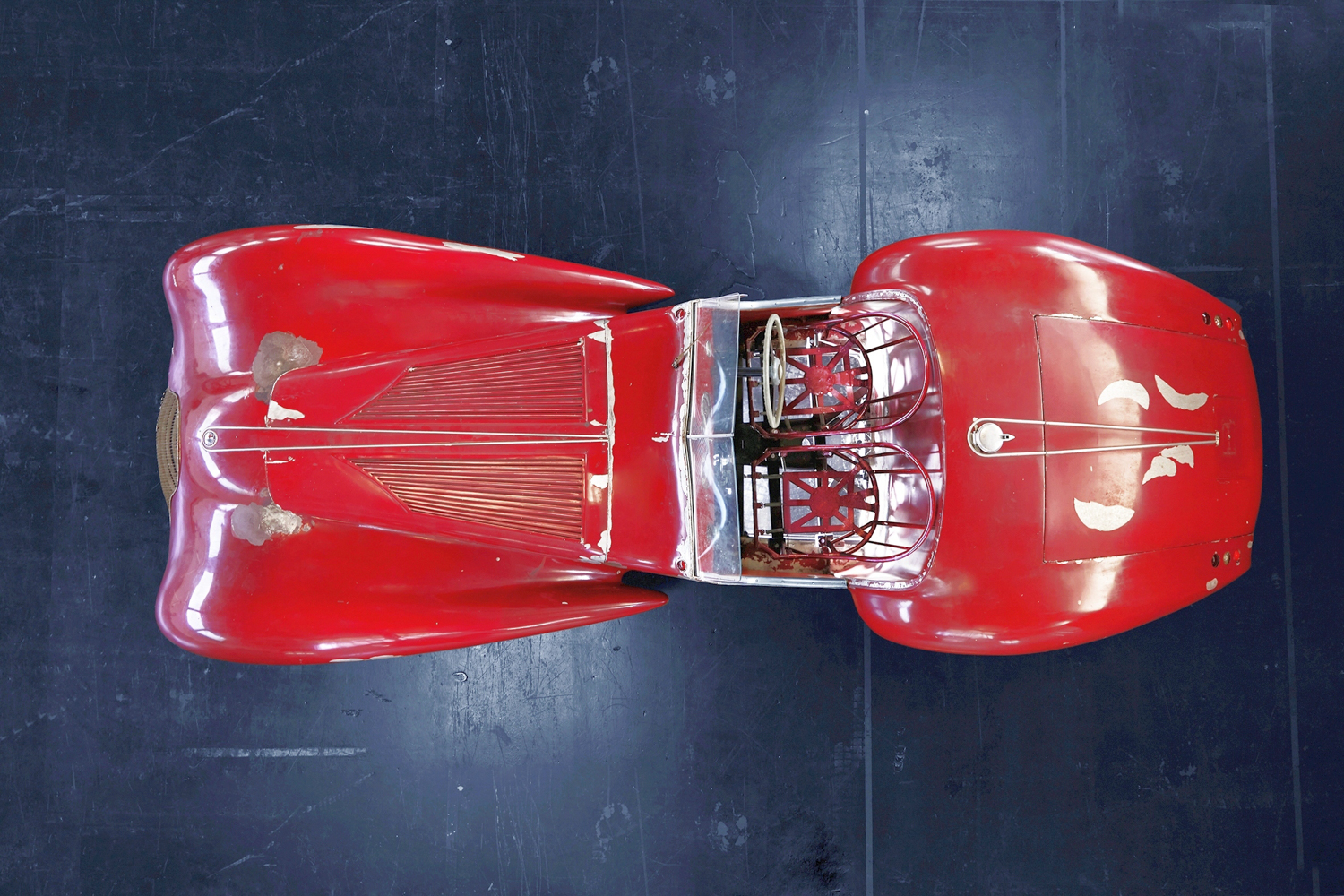

Racing enthusiast Wifredo Ricart encouraged the creation of new body designs for these cars, one a coupe on an existing three-liter Tipo 8C and another a roadster prototype with the V-12 engine in a Tipo 412 chassis. Both have the exotic flair that is associated with the creations of Ricart, dramatic forms, as much Spanish as Italian.

When Enzo Ferrari huddled with Gioachino Colombo after the war, certain precedents reinforced their decision to choose a V-12. One was Alfa’s V-12 racing engine for the 1936 season. Although heavily overmatched by the Germans in 1937 and under-gunned when reduced to 3-liters in 1938, it was the most powerful auto engine that Alfa had hitherto built.

Using frames of the 8C 2900 A configuration, four sports racing cars bodied by Superleggera Touring were powered by this V-12 in 1939. Unblown, it produced 220 bhp at 5,500 rpm. In 1939, these Tipo 412s competed at Antwerp and Luxembourg with success.

As described above, Trevisan had led the design of V-12 and V-8 engines for the prototypes of series-built Alfa Romeos. Retained for the sports V-12 designed in the Reparto Sperimentale by Colombo was the distinctive feature of single overhead camshafts driven by chains at the front of the engine. Here was a concept later carried over by Colombo to his V-12 for Ferrari.

The choice of a single overhead camshaft for each cylinder bank, in the style of Trevisan, was crucial in Colombo’s creation of a Ferrari power unit that could excel in both racing and road cars. In the crankcase, with its seven main bearings, experts have detected close similarities between Trevisan’s 12 and the first Ferrari V-12. Colombo saw no reason to ignore successful precedents in creating an engine for Enzo.

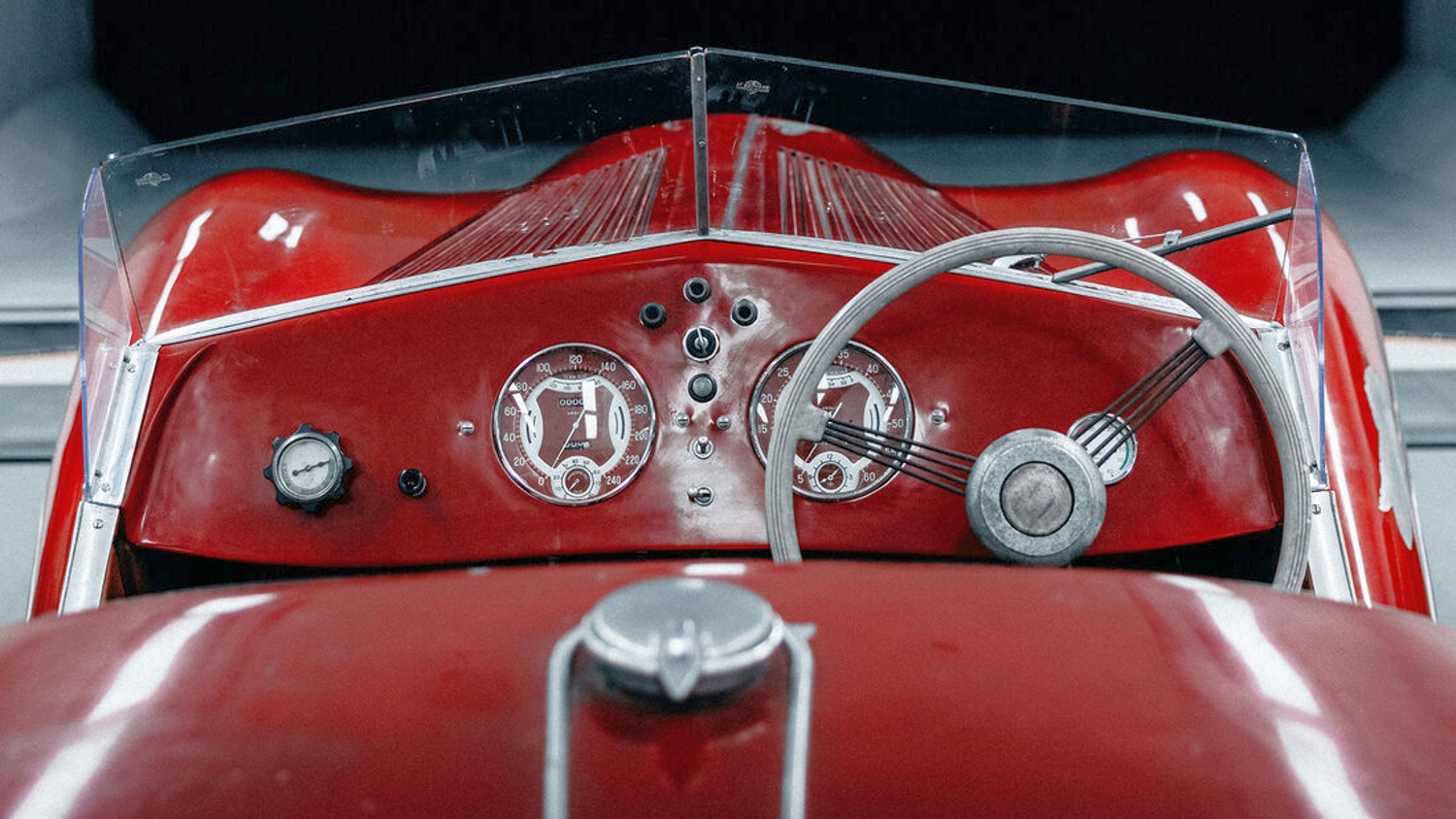

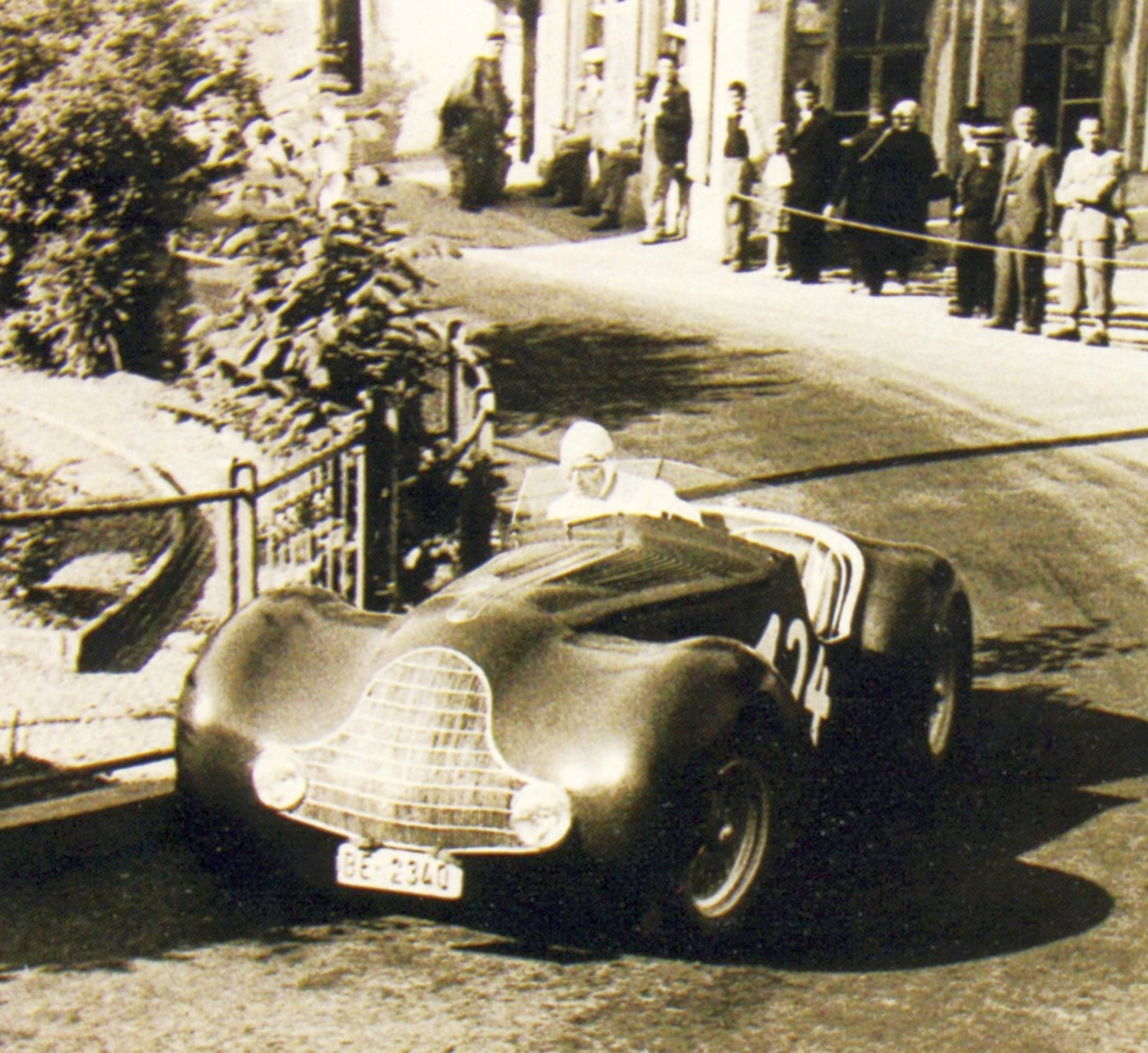

After the war, some of the Reparto Sperimentale components and the exciting and unique roadster came into the hands of Switzerland’s Jean Studer. From 1947 through 1951 he raced it seven times, all in Switzerland, winning twice and placing second twice.

It came to light again recently in the ownership of Stefano Martinoli and his Progetto 33 AG, who entrusted it to Austrian restoration specialist Egon Zweimüller. They commissioned his expert team to bring it back to life, without erasing the lesions that bespeak its dramatic history.

Switzerland-based Progetto 33 dubbed the car “12C Prototipo” in recognition of its survival as evidence of the engineering and racing ambitions of Alfa Romeo’s Ugo Gobbatto, Wifredo Ricart and Gioachino Colombo. Like its participation in Formula One with Sauber, the 12C Prototipo bears unique testimony to Alfa Romeo’s spectacular engineering, determination to survive two wars and renewed commitment to the very best the motorcar world can offer. Its story would be worth a book—keep an eye out for just that.