Canadian motorsports owes a huge debt to the team of Jim Fergusson and his wife, Alice. Their efforts were almost always voluntary and for the love of the sport.

Jim was not only a successful motorcycle, sports car and sedan racer but also a rallyist, as well. If that were not enough, he took on the roles of team manager, crew chief, mechanic, race and rally organizer, official and patron of the sport. And, if even that were not enough…he was also a race car designer and constructor.

Jim’s wife Alice was one of Canada’s pioneering female race and rally drivers. In the stone-age days of “powder puff” races for the ladies, she decided that she wouldn’t put up with that stuff. No, she preferred to compete against all comers and she was successful, sometimes in a Citroën DS19 four-door sedan of all things.

But again, as if that wasn’t enough on Alice’s resume, she was also a race and rally organizer and the editor of the British Empire Motor Club’s Small Torque magazine, most likely the oldest racing club magazine in Canada. Today, back issues of the magazine provide not only a snapshot of motorsports back in the day, they also provide a valuable resource for the history of motorsport in central Canada.

To wind up their motorsports careers, Jim and Alice entered their truncated, customized Citroën DS19 in the 1972 edition of the Brock Yates organized Cannonball Run. What follows is a summary of their varied efforts not only to compete in motorsports events, but also what they did to promote motorsports in Canada.

Jim Fergusson was born in Brandon, Manitoba on January 31st, 1910. His father ran a grain elevator and carriage repair shop. Jim inherited his father’s mechanical aptitude. However, he added great curiosity to his native borne ability. He also brought a love of speed to his innate curiosity. Early on he loved to explore the countryside around Brandon on his old motorcycle. In 1924, the Fergussons moved to Toronto, Ontario and in 1928, Jim’s father opened the Scarborough Beach Garage in the east part of Toronto. By a serendipitous coincidence that was the same year a group of Toronto motorcycle enthusiasts formed the British Empire Motor Club or BEMC. Five of the originals became constant visitors to the Fergusson garage. They introduced Fergusson to motorsport through motorcycle racing, and he jumped into the motorcycle racing water in a big way. At about that time, there was a 24-hour race on a 16- mile circuit on the rough dirt roads of the Caledon Hills, north and west of Toronto. Jim, riding an AJS motorcycle crashed out in the early morning hours. In spite of his inauspicious beginning, he was hooked. And, he was hooked into joining BEMC too, serving as president in the late 1930s.

Many of BEMC’s earliest competitions were gymkhanas, trials, scrambles, and ‘mud runs.’ Then, he hit the dirt. The BEMC boys raced on the fairground bullrings of southern Ontario, at the Canadian National Exhibition grounds (Site of today’s Toronto Indy races) and at the famed Woodbine course in Toronto (Scene of the famous Queen’s Cup horse race).

Of course, this was the time of the Dirty Thirties and the Great Depression and so Jim and some of his BEMC friends went on the road, racing at dirt tracks across Canada and the United States.

One of Jim’s barnstorming friends was Eric Chitty who went on to build a legendary career in British Speedway racing. In later years Jim raced with Tony Miller who lost an arm when he crashed out of the lead in the first Daytona 200 in 1938. Jim also became involved in pre-World War II Canadian road racing, such as it was back then. He raced in BEMC’s Bayview Heights road races in 1932, at Daytona in 1938 and 1939. He also competed in the Wasaga Ontario Beach races in the late 1930s.

The pace the boys led in those days was gruelling to put it mildly. It was a nomadic life. If Jim and his friends won and the promoter actually paid them, they would sleep in a hotel. If not, they slept in their tow car. The pace was both frantic and tough and the boys developed a system to drive to as many races as they could without stopping. They would switch drivers by having the relief driver slide over from the passenger side while the driver being relieved would go out the door, down the running board, over the motorcycles on the trailer then up the other side of the tow truck to re-enter on the passenger side door. Glitches did occur. For example, one night, Tony Miller, one of the team drivers stepped on the un-fendered wheel of the trailer carrying the team’s motorcycles and was thrown into a ditch. His teammates drove another 20 miles before they realized they had lost him!

During the barnstorming days, Jim met a young Toronto woman named Alice Clarke. She was an exceptionally talented and athletic young woman who was involved in baseball, archery, golf and skiing all at a competitive level. She demonstrated a competitive streak in every sport she took part. Jim and Alice dated for a few years before they married in 1939, just before World War II started. When Canada entered the war, Jim’s career in motorcycle racing came to an end. He joined the Canadian army and instead of servicing motorcycles he went overseas where he ran an engine building company in Britain during the war. After D-Day, he took charge of a motor pool, recovering and repairing tanks.

After the war ended he was demobbed and returned to Canada.

During the war, Alice ran the Scarborough Beach Garage and kept the business going by storing automobiles and motorcycles for owners who were in the services. Alice also kept the meeting place for the BEMC crowd, holding gatherings for those members who were still in Canada.

Things changed for the club after the war and after the return of veterans who had made England their home during the conflict. Many retuning members had encountered the British sports car, the MG series cars which had been a decided rarity before the war. Jim had been one of the rare owners of this type of automobile: a 1928 MG 14/40 that he had purchased in the late 1930s. With a background in this type of car, he was well positioned to service the burgeoning sports car boom. The Scarborough Beach Garage was doing well, and so Jim started a dealership, Jim Fergusson Motors on Yonge Street in Toronto, selling a wide variety of makes: MG, Morris, Jaguar, and Citroën. He expanded in the early 1950s by selling Nash-Ramblers, Willys-Jeeps and Studebakers.

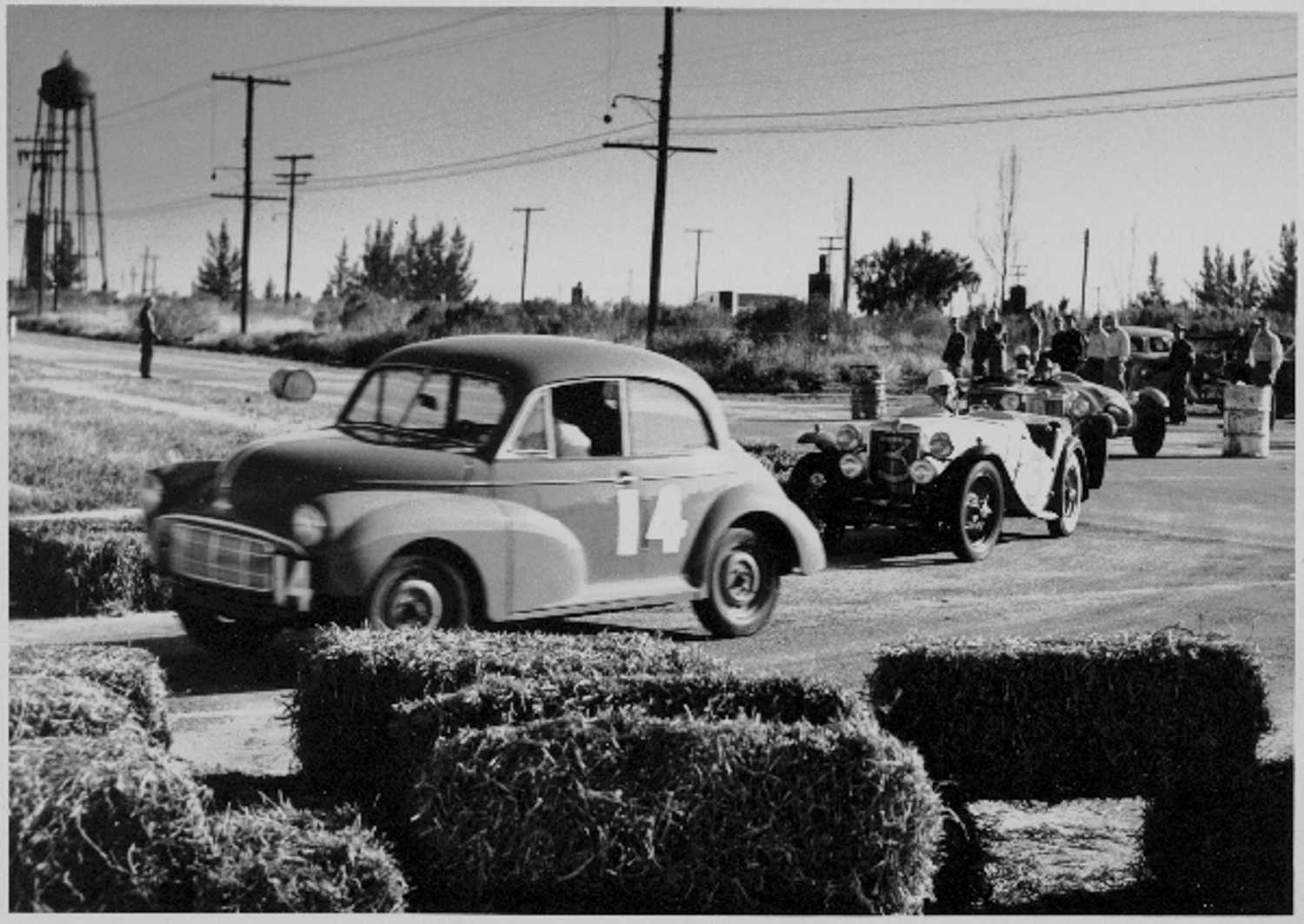

In 1950, BEMC expanded its activities by getting into automobile racing. Jim was president of BEMC at the time, and he was one of the leaders in moving the club into automobile racing in Canada. Thus, on June 25, 1950, BEMC organized and hosted a pair of races at the Edenvale racetrack, just south of Georgian Bay, Ontario. As far as we know, this event was the first known organized sports car race in Canada. Jim finished third in both Edenvale events driving a stock MG-TD. Alice finished 15th in the first race driving a Fiat 500. She probably was the first Canadian woman racing driver. Jim and Alice were about to embark on a decade of racing and rallying. Not only did they race at Edenvale, they also competed at Sebring – in the very first six- hour event. They also competed at Watkins Glen and the Carp racetrack in eastern Ontario. Then, they raced at Harewood Acres, Green Acres and other circuits. They rallied in BEMC club events, the Canadian Winter Rally, and the Trans-Canada Rally. They also kept busy by competing in hill climbs, ice races, economy runs and other competitions.

On December 31, 1950, Jim drove in the first Sebring race, the inaugural Sam Collier Memorial Grand Prix of Endurance. It was a six-hour handicap race. Jim finished 11th overall and second in class at the wheel of a stock Morris Minor from his showroom floor. He drove the full six hours without a relief, one of only two drivers to do so. In September of 1951, he drove in the Watkins Glen Queen Catharine Cup race, again in the little Morris Minor. He finished 11th out of 32 starters in a field, which featured some purpose-built race cars.

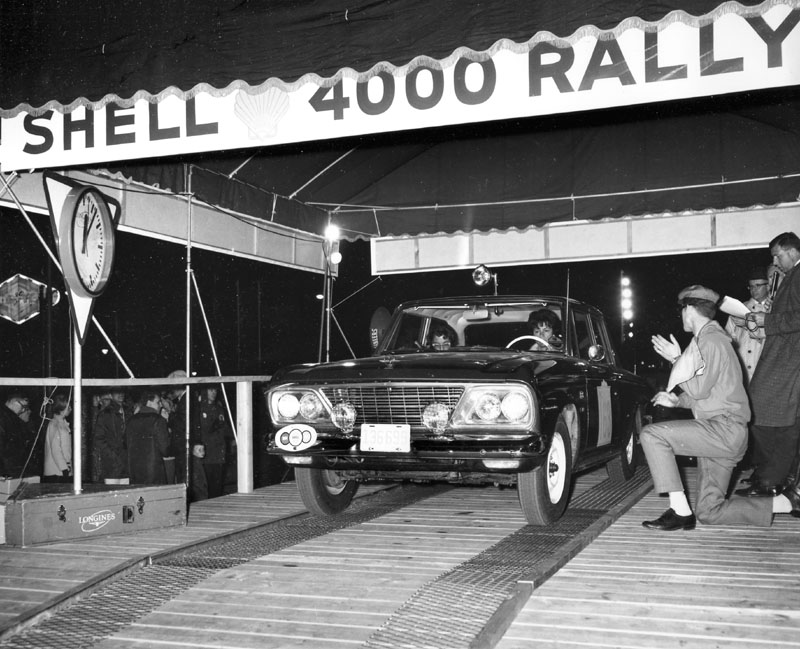

In addition to racing, both Fergussons, Alice and Jim, were heavily involved in the early history of Canadian rallying, both in organizing and competing. They helped to survey and lay out the course for the first International Canadian Winter Rally in 1953. It was the only edition of the rally to include a circumnavigation of Lake Ontario. That winter provided the longest and coldest event in the long history of the Winter Rally. Jim and Alice co-drove in a Nash and tied for first place with three other crews. The Fergussons managed successive teams, which won the rally in 1954 and 1957. Alice was second in the Coupe de Dames in 1959.

In the 1950s, Jim competed in a variety of British sports cars, but he was most successful in small displacement sedan races, competing in such cars as Morris Minors, Austin A10s and a Nash Metropolitan of all things. Later in his racing career, he raced a Citroën and small Studebaker sedans. After the Morris Mini Minor came into his showroom, he ran one of those as well.

Jim was a vocal proponent of the small and nimble sedan, at odds with the North American ethos of the time where bigger was better, and the heavier the better to corner and handle more easily. At one time a Toronto newspaper ran one of his articles titled “Fins are for Fishes.”

Jim and his wife Alice were amateurs in the sense that they competed for the love of the sport, but their efforts had a commercial side as well. They competed in cars, which they sold at Fergusson Motors. Racing and rallying the cars they sold demonstrated that not only could a small car compete with the powerhouses, it could win as well. Their successes were often featured in their dealership’s advertisements. They were amateurs, but they brought a level of professionalism, which was lacking in the early days of Canadian road racing and rallying.

Not only did they operate a dealership and garage, the Fergussons owned one of the first “Speed Shops” in Canada. A 1952 advertisement for the Fergusson Speed and Sport Equipment Company offered “speed and sport equipment for American and foreign cars.” Alice Fergusson played such a major role that she was noticed by the local media in a very staid Toronto of the 1950s. Robert Fulford a Toronto Globe and Mail reporter commented on her motorsport role: “Feminine Touch: Woman Constructs a Feature Winning Stock Car Motor”:

Mrs. Alice Fergusson, housewife and motor mechanic extraordinary, sat in the CNE grandstand last night as the motor she built only a month ago won the feature race of the program and also set a record for the third of a mile track. The engine constructed by sports car driver Jim Fergusson’s wife in her shop powered the car which carried Ted Gilbert to his initial first place of the season in the 20 lap, 20 car feature two hours after it pushed his Fabbri Special to a new record.

The Ford flathead engine of Ted Gilbert won the CNE feature (Canadian National Exhibition grounds) for the next two weeks running, a rare achievement, given the high level of competition there. Jim Fergusson contributed to the advertisement of the speed shop’s wares by making an occasional foray to the Pinecrest Speedway with a Ford, which was so stock it carried license plates! Crossovers between road and oval racing were a rarity back in the 1950s, but Jim had gained a reputation of racing anything anywhere at any time.

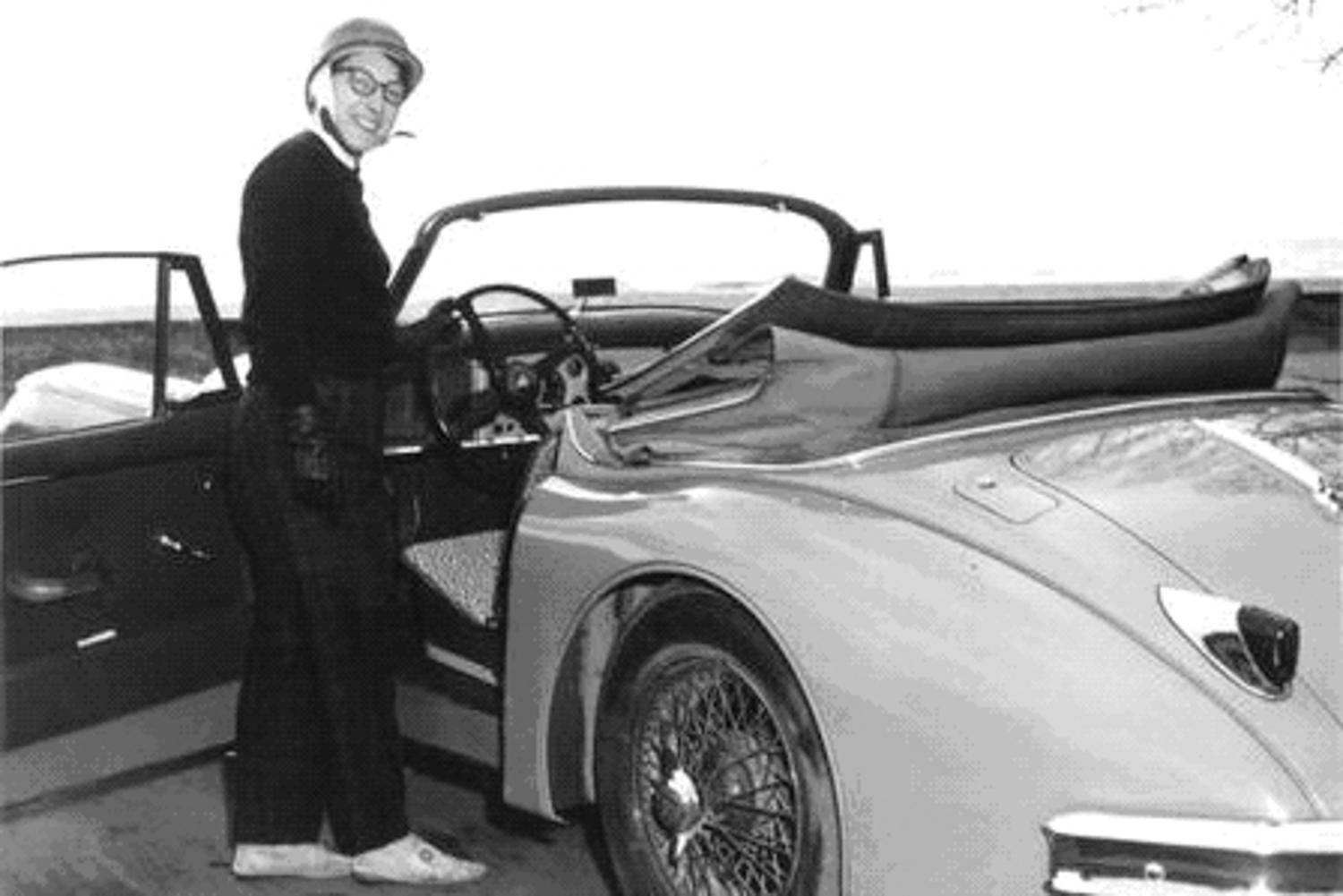

It was not long before the Fergussons’ road racing successes caught the eye of the manufacturers. In the mid-1950s, Donald Healey and BMC came calling. Fergusson Motors had started selling Nash-Healeys in 1950 and Austin-Healeys when they first appeared in Canada in 1953. In 1954 Donald Healey produced a special competition version of the Healey 100 called the 100S. BMC and Healey produced 55 and BMC wanted these special versions only in the hands of the most competitive teams available. Two of these rare cars came to Canada. Jim Fergusson obtained Healey Chassis number 3503, the third Healey 100S produced. Finished in red with black trim, it soon established a fierce reputation. Jim won a number of races and hillclimbs in the car, and he defeated long time road racer Allan Millar in a particularly competitive race at the old Harewood Acres track, a race which Len Coates captured in his book on Canadian road racing, Challenge: The Story of Canadian Road Racing. The anecdote captures the low key, light-hearted spirit of the days when eccentric characters abounded and hijinks were part of the sport:

It happened at Harewood in one of those hour-long Le Mans features. Millar and Fergusson were each driving an Austin-Healey S, hot rod versions of the old four-cylinder Healey. If anything, Millar’s car was a shade faster than Fergusson’s and Millar led the race the entire distance, holding Fergusson at bay until the final corner. As they went into the final turn of the race, Fergy suddenly blasted his horn, loud and long. Now, nobody toots his horn in a motor race. It was probably the first time Millar had ever heard a horn honking while he was on the track. Almost instinctively he moved over, giving Fergusson a hole large enough to squeeze through on the inside. Fergusson roared past and won the race.

During his time with the Healey 100S, Jim’s focus began to turn from driving to team managing. Thus, he allowed other drivers to take the wheel of the Healey. In 1955, he entered it at the Sebring 12 Hour Race with the experienced drivers Bob Wilder and Rowland Keith as his team drivers. They finished 32nd in a field of 80 cars.

After the Healey, Fergusson ran a team of MGAs with Brian Rowntree and Ed Leavens doing most of the driving. With Roly Keith and Ed Leavens, they finished 23rd overall and 2nd in class at the 1957 Twelve Hours of Sebring. “Foxy Fergy” as journalist/historian Len Coates called him, excelled at managing cars in long distance races. Coates wrote,” If Jim Fergusson was managing your car in a long -distance race, there was little to do but listen carefully to everything he told you, do it then show up to collect the awards at the trophy presentation.”

Jim’s craftiness was on full display in the four-hour relay race at the Harewood Acres track in 1958. When a car stopped for fuel the rules required that it be replaced by another team car and driver. Each team had at least two cars and some had three or four. Jim entered Alice in a special Citroën built in the shops at Jim Fergusson Motors. They cut 21 inches out of a Citroën ID-19, turning the four -door sedan into a light, nimble two-door coupe. Hidden in the trunk was an enormous fuel tank. Alice drove the full four hours without a stop.

While the other teams howled in protest, Jim reminded them that the rules set no minimum number of cars or drivers per team, and that a change of driver was only required when the car made a pit stop. The Citroën lived on to enter the first Cannonball Rally in 1972. Alice quit racing after the 1958 season although she continued to enter rallies until the late 1960s.

Alice developed her stamina as a young athlete and her excellent physical condition enabled her to do well in long distance events like the 1961 Shell Trans-Canada Rally, a gruelling 4,100-mile trek from Montreal Quebec to Vancouver British Columbia. In this event, Alice and her co-driver/navigator Gillian Field finished 35th out of 116n entries. She was the leading woman for most of the rally. It was only at the very end that a typographical error was discovered that gave the women’s trophy to Denise McCluggage, dropping Alice and Gillian to second place. While Denise drove a new Corvair with full GM support, Alice and Gillian drove the rally in one of the Fergusson’s baby Citroëns. During the celebration, a photographer snapped a photo of Alice smoking a big cigar. The photo appeared in newspapers across the country and Alice received more publicity than the winners of the rally, Jack Young and Reg Hillary. Alice rallied through the 1962 and 1963 season, driving for the Studebaker factory team with her husband as team manager.

Jim also built specials, which demonstrated his skills as a designer and engineer. We’ve already mentioned his cut down Citroën, but he had already created his big-engined special labelled as “Mother Goose,” an MG-TC with a six-cylinder GMC engine. With three times the cubic inch capacity of the original engine, it was a torquey car, which wore out its brakes rapidly on the track. However, its low-end power made it a formidable hill climber.

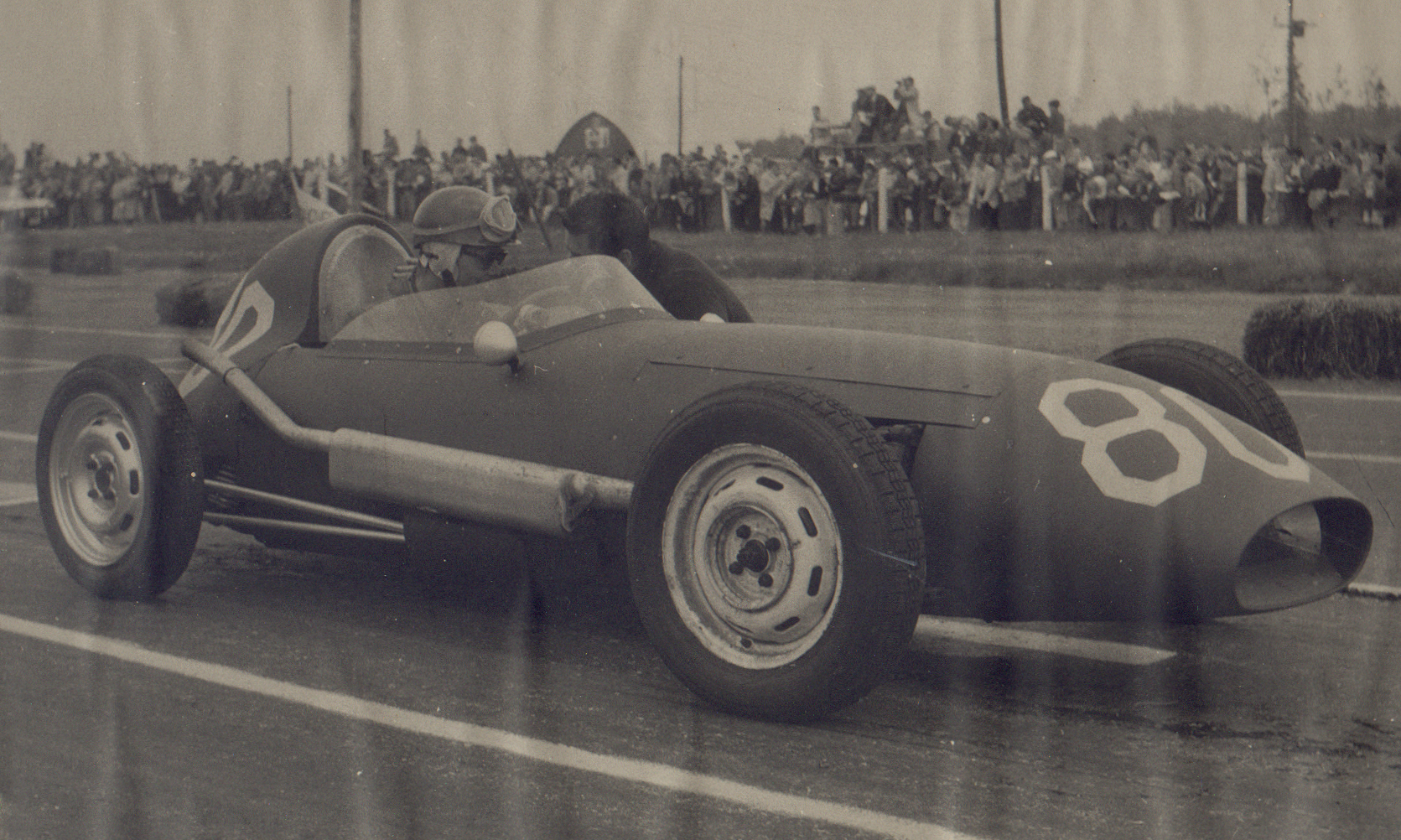

In 1960, Jim designed and built a Formula Junior car, which bore his own name. He wanted to see if a Canadian car could take on the Formula Juniors, which were being imported from Britain. At that time, front-engined cars like Elvas were still competitive with the mid-engined racers built by Cooper and Lotus. Jim’s design was unusual in that it was a front engine-car with front-wheel drive. Without having to run the drive shaft through or around the cockpit as in its contemporary competitors, the Canadian built Sadler Fjr and the Stebro Fjr, he could save weight and sit the driver low in the frame. Because the engine was right behind the driven wheels, the car would have superior traction. For an engine, Jim used the engine and transmission of the East German DKW.

The engines came from two-stroke specialist Gerhard Mitter. Craig Fisher stated that the engines came to Fergusson and that he was under strict instructions not to touch them. After a certain number of races, Fergusson was to send the engine back to Mitter for rebuilding. However, the engines were mediocre, as was the case for most DKW engines. Ed Leavens one of the drivers, had three-straight second place finishes in 1960 at the Green Acres track and at Harewood. By 1961, the mid-engined cars ruled, but Craig Fisher in the “Purple People Eater” as he called it, still managed a second and two thirds at Mosport.

The story goes that one of the car magazines sent an artist to the Fergusson home to do a cutaway drawing of the Fergusson car. The artist wanted to see the blueprints to do his drawing. However, he became exasperated and disappointed when – with great aplomb, Jim unfolded a huge sheet of paper. It was blank, except for a tiny doodle of the car’s basic layout on one corner of the “plans.”

Jim and Alice were organizers and builders of the sport, as well as competitors. The two of them were on the executive of the British Empire Motor Club and were not above involving their children in their activities. In particular their two daughters spent part of their youth sweeping up the tracks BEMC leased for racing events. As many of the tracks bordered farmland with cattle left to wander freely, the girls’ tasks often involved removing bovine by products. They truly contributed above and beyond the call of duty to the operation of the club’s activities.

Operating airport tracks was the norm in the early days of Canadian motorsport but in the late 1950s, BEMC membership began thinking and working toward the creation of a permanent purpose-built track east and north of Toronto: Mosport. Thus, it was that Mosport Ltd was created to bring the dream into reality. When the company Mosport Ltd was created, the Fergussons were among the first shareholders. The club stared issuing $100 debentures to pay for the construction of the track and the Fergussons purchased and sold them. They also encouraged groups to purchase them as well by driving them out to the construction site. All was not well with the track however and at the end of the 1962 season, Mosport went into receivership due to the debts incurred during the track’s construction. To keep the track open, the Canadian Race Drivers Association or CRDA and BEMC formed the Mosport Racing Partnership to keep the track open. National Trust, which company held the debt leased the race track to MRP on condition that none of its events would lose money. Jim Fergusson was one of the two BEMC representatives on the five man board of MRP and he assisted in keeping the track afloat until it was eventually purchased by Cantrack Publishing – publishers of the Canada Track and Traffic magazine.

The Nash and Willys brands both went through corporate upheavals in the 1950s with Willys disappearing and Nash being incorporated into American Motors. Likewise, Studebaker, Fergusson Motors’ leading domestic brand was in serious financial trouble. The Canadian government’s efforts to prop up Studebaker’s Canadian production (subsidies) eventually led to the Canada-US Auto Pact and effectively knocked most of the British imports out of the Canadian market. Because their business had slowed down to a trickle, Jim and Alice took a deep breath and moved to Pennsylvania. Otto Linton, veteran driver and dealer stated that Alice Fergusson worked for him during her time with Jim in the USA. Jim became a Jaguar dealer and then a distributor for Lancia, Maserati and Ferrari. He did some rallying and helped the Lancia team at Sebring.

Jim took one more kick at the can in two-wheeled motorsports when he entered a motorcycle trial. He had been absent from two-wheeled competition for at least 15 years and he entered as an amateur. He finished second overall and was awarded professional status. Not only that but he was elected to the Society of Automotive Engineers although he had no university degree and all his skills were self-taught.

Alice and Jim’s “last hurrah” in motorsports came in 1972, when they entered the first Cannonball Run. They had heard of the clandestine cross-country run through the racer grapevine and entered their close-coupled Citroën DS19 fitted with a 60-gallon racing fuel cell to cut down on the number of stops. The stories that came out of that trip are legendary. Their fuel stops were timed like a Sebring pit stop. Whatever they had to do, and their crew included their dog, they had to do it in the time it took to refuel. They took the longer but more-wide-open southern route across the USA. One time, they flew through a speed trap in Texas and a motorcycle cop gave chase. However, as the story goes, when he pulled up alongside the beetle shaped Citroën and saw a distinguished grey-haired gentleman at the wheel and a poodle in back, he just shook his head and waved them on. Jim, Alice and the poodle finished 15th in the first Cannonball. They crossed the USA in 42 hours and eight minutes at an average speed of 68.9 miles per hour. They bettered their time on the drive home after the race.

Jim Fergusson died in Pennsylvania in January of 1976 and many of his old BEMC comrades made the trek down for the funeral. True to her husband, Alice turned his funeral procession into a car rally which ran on freeways, down dirt roads, over a covered bridge and even fording a river. The funeral director according to one witness said, “I know a shorter way,” to which Alice replied,”Can’t you make this thing go faster?” Alice passed away in April of 1997.

Alice and Jim Fergusson were inducted into the Canadian Motorsports Hall of Fame in 2004.