What is it about a Stradale?

Ask most Alfisti what Alfa they’d most like to have in their garage, and a significant percentage will say a Tipo 33 Stradale. I’ll admit, I’m odd, since my choice would be a Giulia TI Super, but the Stradale is a close second even for me. So, what do you do if you REALLY want a Stradale? There are very few of them, they sell for astronomical prices when they sell, and no one who owns one wants to sell theirs. If you’re David Simmons, you recognize that it’s unlikely that you’ll ever be able to buy one, so the answer is simple – Build It!

I’ve known David and Eileen Simmons for a long time. My daughter and I crashed their New Year’s Eve party some 30 years ago on our way to Santa Fe to ski, and they were happy to put us up. The Simmons are complete Alfaholics. He says, “I’ve been an Alfa person since 1971 when I bought my first one. It [has been] all downhill since then.” They’ve had other kinds of cars, but their garage is always full of Alfas. I don’t know how many Alfas they have right now, but my Ford Flex was the only non-Alfa anywhere on their property when I visited this year. Most of the cars have been restored by David, but there are a couple projects around – a Giulia Super owned by a young friend who visits and works on his car, a Giulietta Sprint that David is in the process of restoring, and the Stradale, which is in the final tweaking stage – it runs, but it still needs a bit of fiddling before it will go on any road trips.

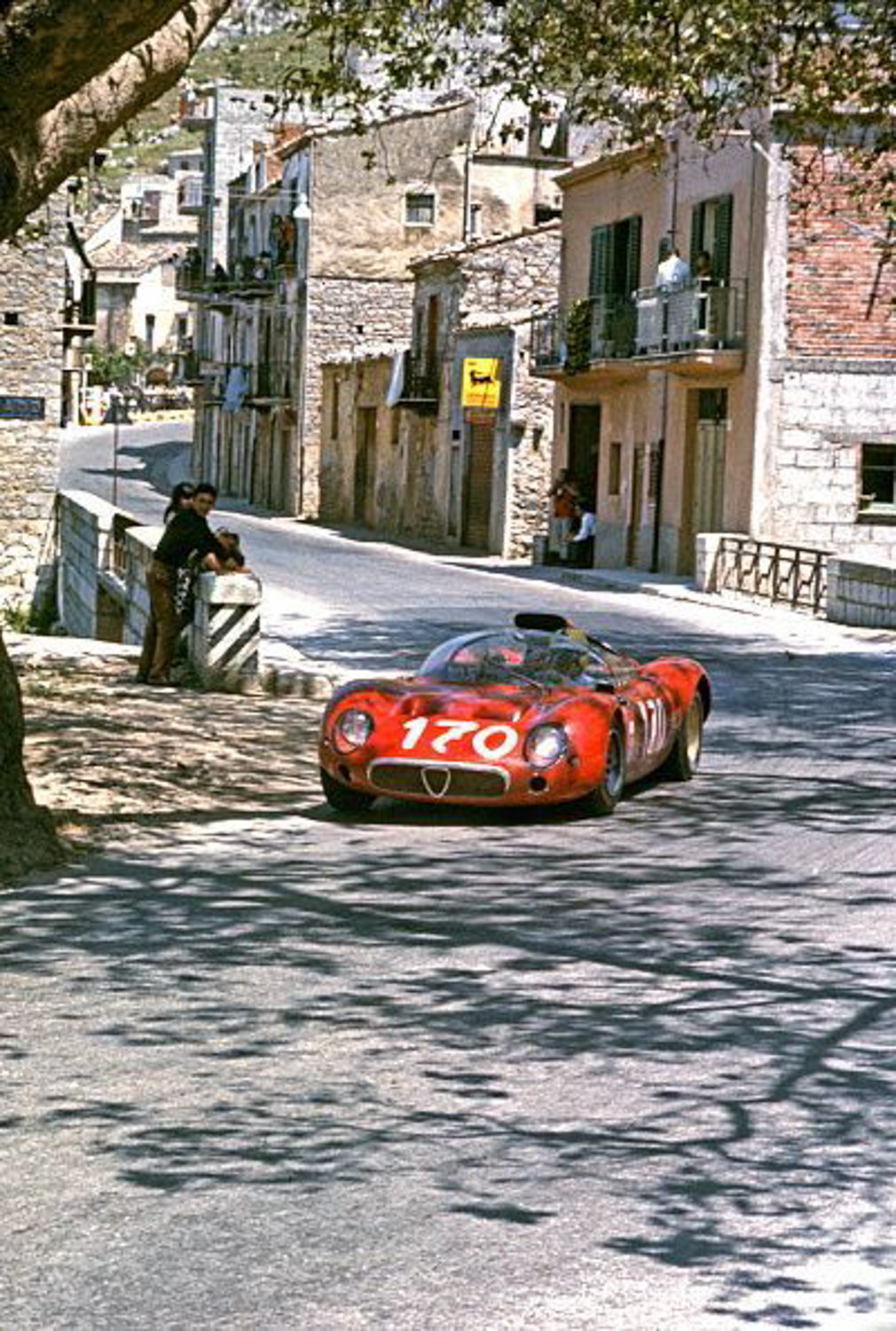

Why is a Stradale so special to Simmons and many other Alfisti? The simple answer is that it is thought to be the most beautiful modern Alfa Romeo. The idea to create the Stradale began with a win at a hill climb in Belgium by the first of Alfa’s Tipo 33 sports racers. When the company decided to return to the top level of sports car racing, the World Sportscar Championship, it began the development of the Tipo 33 in the early 1960s. Initially, the engine to be used was the 4-cylinder from the TZ2, but Autodelta designed a new 2-liter V8 that was mated to the first chassis. The Tipo 33, known by its nickname “Periscopica” because of its tall engine air intake, had its competition debut at the Fléron hill climb in Belgium on March 12, 1967. Driven by Teodoro Zeccoli, the Tipo 33 won that event. Unfortunately, the car proved not very reliable, and its best finish in the 1967 championship was a fifth at the Nürburgring 1000. The 33 was replaced by the Tipo 33/2 the following year.

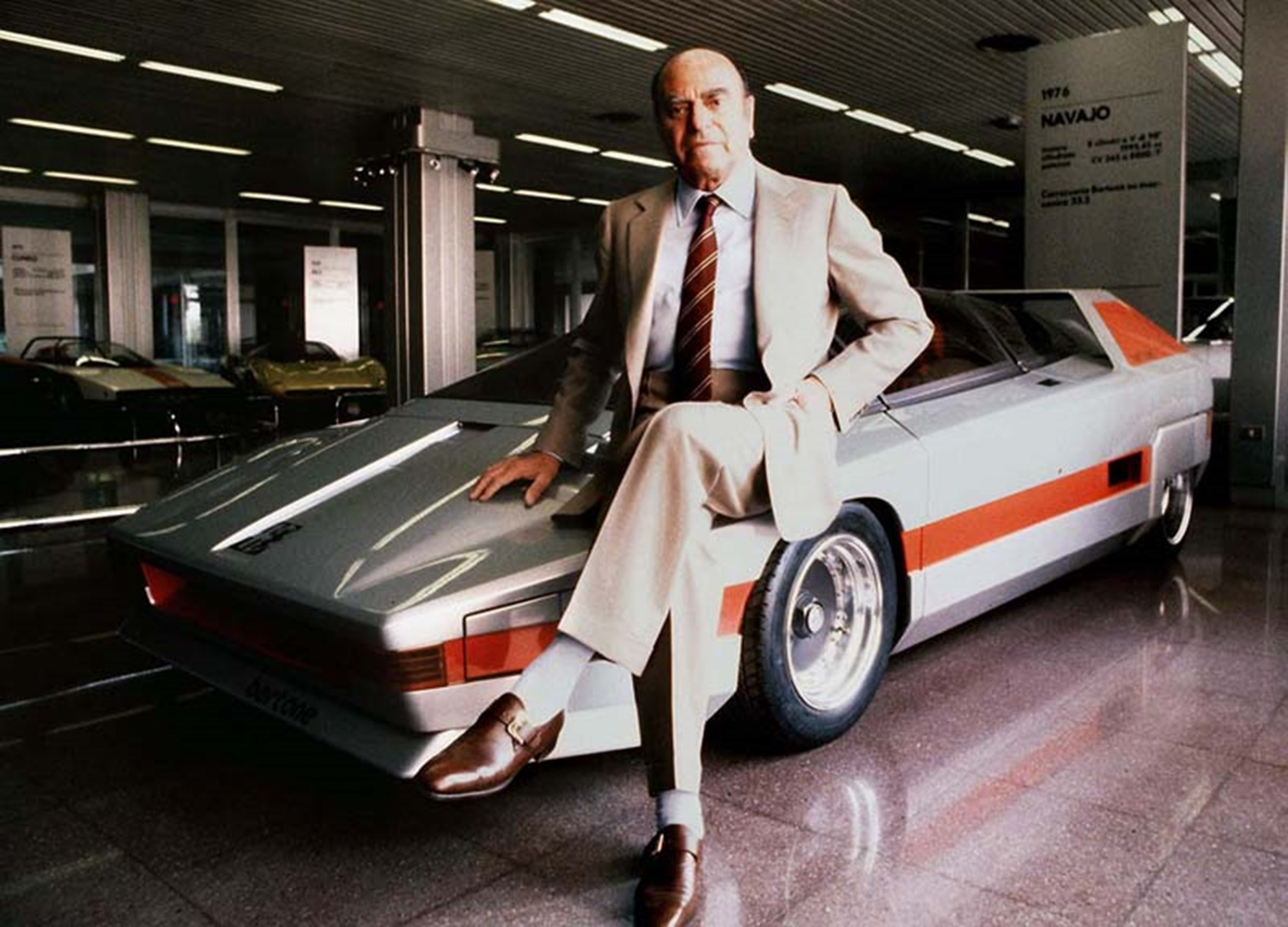

Alfa Romeo’s president, Giusieppe Luraghi, was looking forward to Alfa’s success in the World Sportscar Championship, but he was also thinking about producing an Alfa Romeo road car that would compete with other European “super cars” then being produced, such as the Lamborghini Miura. Luraghi gave that task to Carlo Chiti, one of the company’s top engineers. Chiti had the basic chassis and drivetrain from Autodelta, but he needed someone to design some stunning bodywork. For that, he turned to Franco Scaglione, one of Italy’s most respected designers. Scaglione drew several concepts and showed them to Luraghi. Luraghi pointed to one of the drawings and said, “Let us produce this one.” The car received its name, “Stradale,” which translates to “Road” in English, because it was the road version of the Tipo 33.

Scaglione faced a number of challenges in bring the car to production. First was the dictum from Luraghi that the performance of the road version of the 33 not be more than 5% less than that of the race car. Coordination with Chiti was another problem. Chiti was fully involved with the race programs at Autodelta and had little time to address problems that arose around the road version. One of those problems was the low height of the Stradale – only 99 cm or just under 39 inches, which is an inch lower than the Ford GT 40. Scaglione’s solution was to design dihedral doors that opened upward and included a portion of the roof. Contemporary automobile modifiers often add these types of doors and call them “butterfly doors.” Possibly Scaglione’s biggest problem was the coachbuilder. Apparently, Carrozzeria Marazzi’s shop floor workers were not very well prepared for the task, since they built mostly police and funeral cars. This required Scaglione to spend a lot of time overseeing the work. The Stradale had to be very similar to the race car in many ways, but the cockpit needed to be comfortable enough for road travel while retaining the “sexy” look of a race car. Scaglione created a cockpit that would satisfy anyone who might climb into a Stradale.

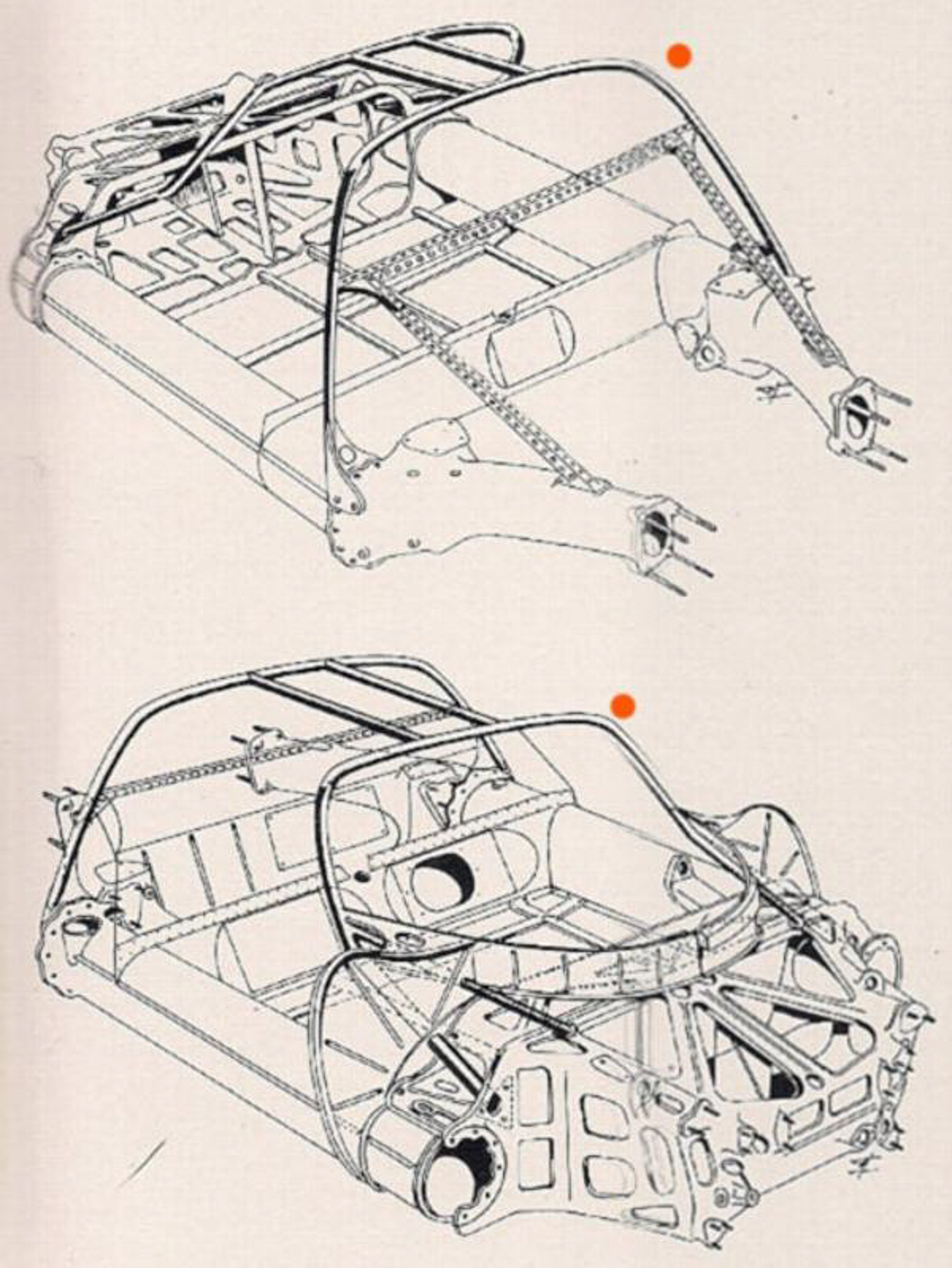

There were many design elements of the 33 that were carried over to the Stradale. One that became important to the creation of the tribute was the location of the fuel tanks. The chassis of the 33 was based on large diameter, riveted magnesium tubes. Two of those tubes ran along both sides of the chassis along what are called the rocker panels on road cars, and they carried the fuel for the Stradale. The purpose of using these tubes as fuel tanks was to insure that the car remained perfectly balanced as the fuel was used.

The Stradale prototype was first shown at the Sports Car Show, in Monza, in September 1967. The original plan was to produce 50 copies of the Stradale, but a decision was made to shift the emphasis to a new model, the Montreal, and so only 18 were actually produced. That number, though, may or may not be accurate, since there are discrepancies in the range of chassis numbers. We do know that two prototypes were produced, and eight chassis are accounted for. The first prototype was different than the second, which is more like the production versions and is the one in Alfa’s corporate Museo Storico. Five more chassis were used by coachbuilders to produce six concept cars – one chassis being used twice. The concept cars, all of which are in the Alfa Romeo museum are:

Carabo and Navajo by Bertone

P33 Roadster, P33/2 Coupé Speciale, and P33 Cuneo by Pininfarina

Iguana by Italdesign

The Stradale was the most expensive car for sale to the public in 1968. In Italy, the Stradale cost 9,750,000 Lire. A Lamborghini Miura was 2 million lire less. If you were looking to buy a Stradale in the United States, you could expect to pay $17,000. The cost of the Stradale may have been one of the major considerations when Alfa decided to focus on producing the 1968 Montreal World’s Fair show car and thus making it the top of the Alfa Romeo road car lineup. The ultimate result is that there are few Stradales in the world and many more Stradale enthusiasts. When demand exceeds supply by so much, the value of a Stradale can only be determined when one comes available in the collector car market, and that value is likely to be one that few are able to afford.

Creating a Stradale

So, how so you start a project to create a Stradale out of nothing? The first thing David did was buy wheels for the Stradale – they won’t fit anything else he has, so it was an acknowledgement that he was actually going to build a car from scratch. It’s not like he hasn’t almost done that already. Most of the Alfas in his garage were close to going to a junk yard when he undertook to restore them. He has a now gorgeous GTC that a friend found for sale in Arkansas and offered to pick up for him. David’s guidance to his friend was to get the car as long as all the odd parts – like top bows and badges – were there. Rust didn’t matter, since David has plenty experience in making new panels. But making panels when you have an original, even a rusty one, to go by is one thing. David had nothing to go by for a Stradale except for some photographs. So, how do you build a car from nothing?

David Simmons retired as a partner in an architectural firm in Tulsa, Oklahoma. He had a long career’s experience in designing things, many from scratch – translating an owner’s ideas into drawings of a home or building and then into plans that can be used to actually build it. During his career, the tools available to transform the ideas into plans became more sophisticated. By the time he retired, David was proficient with 3-dimensional design programs. His firm was one of the first in Tulsa to use a 3-D program, and they chose Archicad. So, he had access to a tool that could help him, if he could find specific information about how a Stradale was designed. Thanks to the internet, he had access to information that would not have been available had he tried to build this car 10 or 20 years ago. Still, you have to find that information. It’s out there in that universe of information and misinformation, and the search can be tedious at best and overwhelming at worst. Thankfully, as a file cabinet full of printed pages attest, it was tedious but successful for Simmons.

Ideally, someone who wanted to copy a Stradale would have access to one so it could be scanned or at least measured, but Simmons knew no one with one of the cars. He was able to get close to the prototype in the Alfa Romeo Museum, Museo Storico, but even they weren’t allowed to touch the cars – he asked if someone could open the door of the car so he could see how the door hinge was made, but he was told it was not possible. Simmons had been thinking about building a Stradale for some time. He said, “It is one of those cars that just kind-of grows on you. To have anything that is a representation of it, you have to build it yourself. I’ve always enjoyed a good challenge. [But] I’d never built a car from scratch before; I’d never welded a piece of aluminum before. I’d welded and restored cars before; I’d made small panels, but nothing from scratch.” Coachbuilders are artists – they are able to make large, complicated body panels out of sheets of metal. Simmons, thankfully, discovered that he was also an artist as he learned how to manipulate those sheets of metal with tools like an English Wheel and turn them into beautifully curved pieces of automotive art.

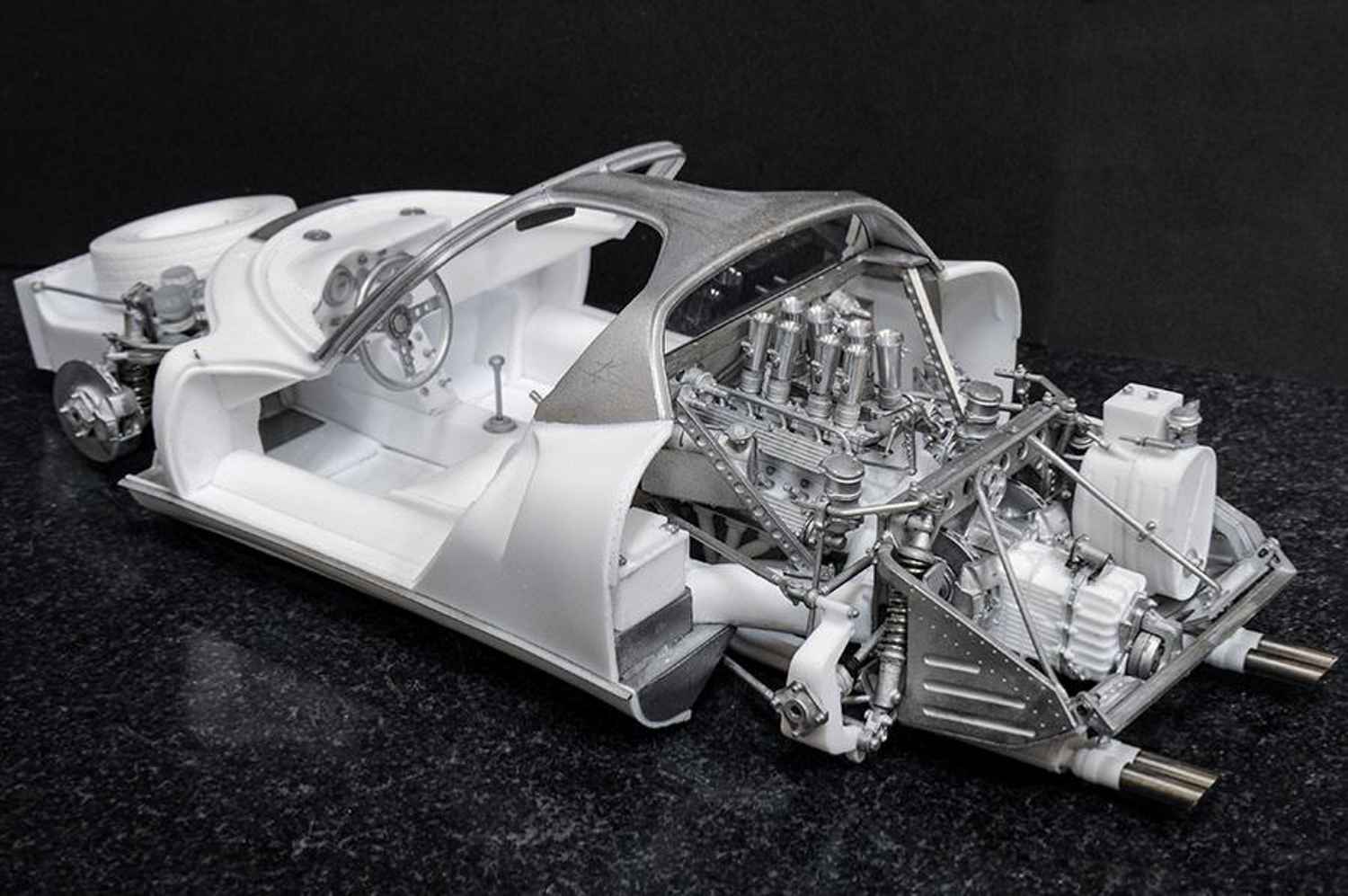

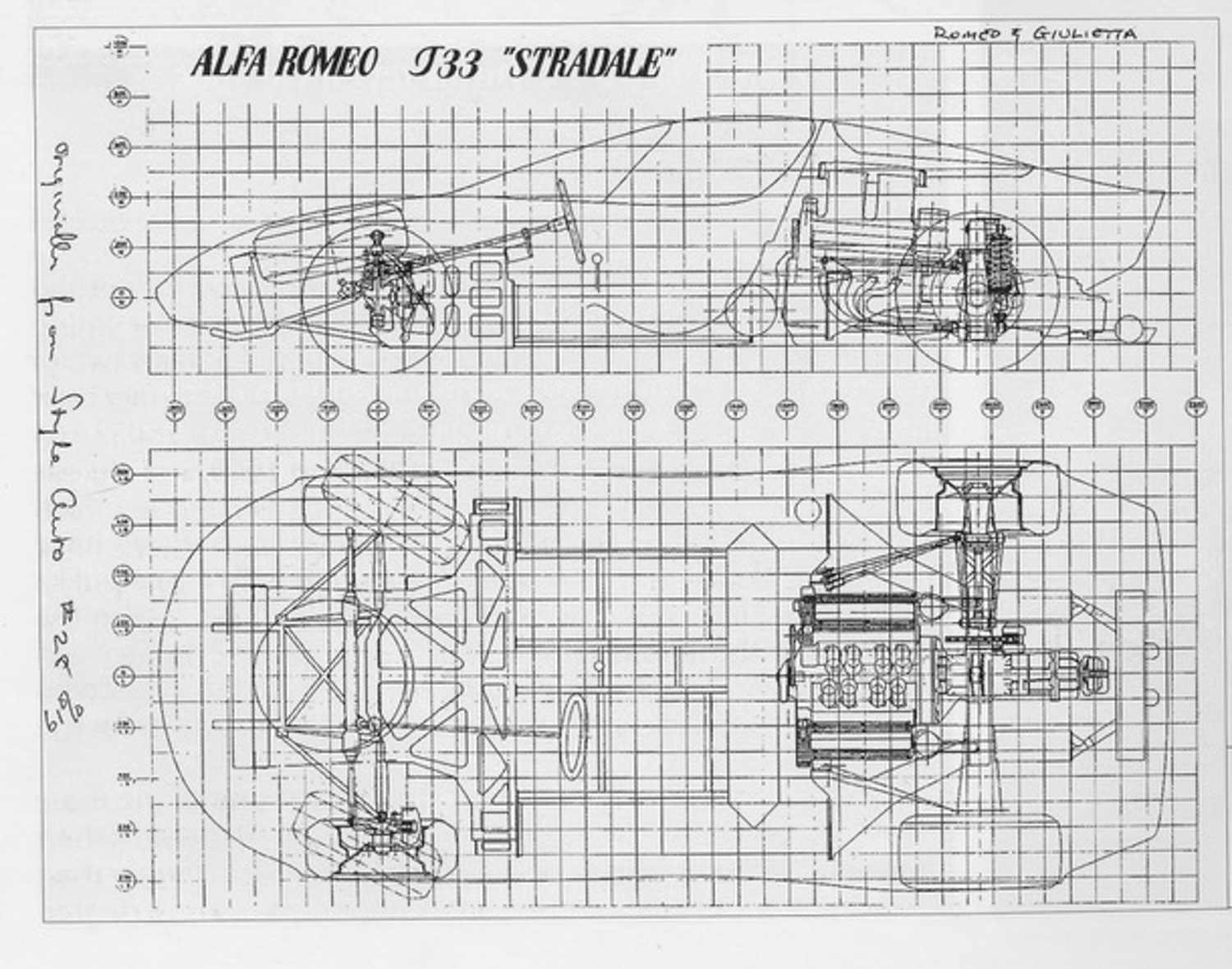

Simmons said he enjoys a good challenge, and, in his pursuit to build a Stradale, that challenge began with the research. The research started about a decade ago while Simmons was still working. He knew he could not focus on building the car until he retired, and that happened in 2015, although he continued to work part-time for a few years after that. Until he retired, he spent a lot of time on the computer looking for details on the Stradale. He found a lot of information, but little of it showed scale. Alfa Power, for example, had Stradale blueprints, but they weren’t scaled so were of limited use. It was the same with the many photos and drawings he found. Without being scaled, there was no way he could size the components. The break came when he found a French source – Autodiva – that had drawings of the car scaled to a 200-mm grid. The site had side, plan, and sectional views, so Simmons had what he needed to figure out how large each part was. He also found a detailed plastic kit of a Stradale made by Model Factory Hiro that gave him a pretty good idea of how the car went together. Now he could begin to make the plans he needed to build the car.

As mentioned earlier, the unusual fuel tanks became a critical part of Simmons’ development of his plans. He measured the size of those fuel tanks and used that measurement to figure out the size of all the other components he would need to build. He could also use the fuel tank measurement to scale parts in photographs. In his words, “I used the side tubes [gas tanks] as my reference plane. I would always have the two tubes in their place and dimensionally correct, [Then] I was able to dimension the photo to the exact size and make these pieces.”

Simmons would carefully trace the scaled parts into his computer for his plans. He was able, for example, to make CAD drawings of the car’s front suspension from which he laser cut the parts from steel plates. In an abundance of caution, Simmons often increased the thickness of parts to insure they would be strong enough. Simmons hand built pretty much everything that had to do with the chassis, suspension, and body. Once he had the chassis built, he undertook to create body bucks from wood so he could form the body panels.

Simmons said, “There is an entity, called the Fab Lab, that was created to allow engineering students from the University of Tulsa access to equipment to build prototype projects. [It] is also available to the public at a minimal charge.” The Fab Lab has a CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machine, 3-D printer, and programs to help the students. He spent several evenings at the lab entering his plans from is computer into the CNC program, then cut the body bucks for the Stradale. He hauled all the bucks home in his Fiat Abarth and mounted them on the chassis. Then it was time to form the body, and many hours were spent on the English Wheel forming and adjusting the body panels.

There were still challenges, since there were parts he could not make that needed to be sourced. Finding a period-correct Alfa V8 was not possible, so Simmons opted to use a 3-liter Alfa V6 from a 164L. He had to modify the cooling system and added an updated fuel injection system. The transmission he selected came from GTO Racing in England and is a Renault UN1 with revised Quaife gears and a limited slip differential, a system used on GT40 cars. “There are a few pieces taken from Alfas – front spindles are from a Giulietta, using the ATE brakes from the ’70s. Rear suspension bits were built around the DeDion hub from a Milano. There’s a GTV rear view mirror.” Simmons explains, “A lot of the fun of the project was sourcing the parts. You never realize how many pieces there are in a car until you have to start finding them individually, and, once you have found several, determining which one will actually work. I probably spent nearly as much time on the computer searching for stuff, as I did building the car. One example is the slave cylinder to mate up with the UN1 transmission and the Alfa 6. I tried several and finally would up with a slave cylinder for a Formula Ford. You have to have a strong left leg because the clutch is really stiff. It’s not going to be a town car.”

Simmons says he has a long list of suppliers, around 90 with many others lost or deleted. The engine computer system, for example, is an SDS system from Canada that still uses the Alfa Romeo 164 distributor, and it gives the engine a bit more power than stock, and probably more than the original V8. He found a source for Hime joints when he attended the Chili Bowl race in Tulsa. Quite a few of his sources are racing suppliers. A tedious part of the build was making the wiring harness. He built it “one wire at a time, from point A to point B.”

Simmons believes in making templates – from paper. It’s much easier to make changes to a paper template than to one made out of more substantial material. He has a box full of the templates he made. An example is the templates for the windshield and windows. Glass windshields for Stradales are unobtainium, so all windows would have to be made from plexiglass. Simmons found a shop, Airplane Plastics, in Dayton, Ohio, and worked with the owner to create the windows and headlight covers. Lexan was ruled out because plexiglass has better optics for the windshield and headlight covers. Simmons started with paper templates from which he made metal bucks so fiberglass molds could be made for the windows. For the windshield, a negative mold was made so the plexiglass could be laid up on the inside of the buck. The side and back windows were laid up on the outside of their bucks. Simmons learned an interesting bit of information about plexiglass – it has a memory, so, if once formed it does not fit, it can be put back in the oven, and it returns to a flat sheet.

Some decisions about bodywork and paint were a little unconventional for today. Simmons likes to use lead, rather than Bondo, but he’s very careful when he uses it and cleans up thoroughly afterward. He also wanted the car painted in lacquer. The only source for lacquer paint is in California, where it cannot be sold. But it is legal in other states, so Simmons had a red mixed with a little black in it. “Simmons Red” is a little darker than Alfa red.

Simmons’s Stradale is more like the first prototype than the production versions of the car. His car has four headlights, four louvers across the back, and no vents behind the rear wheels. His interior is like the original cars, and, also like the prototype, his car is aluminum rather than fiberglass, although his cockpit is steel. There are still a few things to do on the Stradale, as well as some sorting to be done, but it runs fine, and it looks great.

Simmons says, “I pinch myself nearly every day to think I ever got this far; that I was ever able to do this.” Everyone who sees this car is happy he did get this far.