After Ettore Bugatti’s death his family decided to keep his car-making company alive. Their creation of the Type 101 was a daring wager on the appetite of the post-war world for a grand tourer in the image of the pre-war Type 57 Bugatti.

If there were a 1930s equivalent of the 250GT Ferrari it was certainly the Type 57 Bugatti. The 250GT’s chassis lent itself to gorgeous bodies by the world’s finest coachbuilders; so did the Type 57’s. The Ferrari was among the fastest sports cars of its day; so was the Bugatti. The 250GT was the basis of race-winning competition cars; so was the Bugatti, versions of which won Le Mans in 1937 and 1939. Both were manufactured in reasonable volume; from 1934 to 1939 Bugatti made 687 of its Type 57. Thus when the announcement came after the war that Bugatti would produce a new and improved version of its Type 57 there was no little excitement in the world of cars in general, and the world of Bugatti fanatics in particular.

Ettore Bugatti was 65-years old when the doors of the first post-war Paris Salon opened on October 3, 1946. Since 1932 this phenomenally creative engineer, entrepreneur and industrialist had spent most of his time in Paris, away from the feudal splendor of his works in France’s Alsace-Lorraine. There his talented son Jean had been in charge; the creation of the Type 57 was Jean’s achievement. But Jean died in 1939, at the age of only 30, while testing a Type 57 on roads near the factory. Most considered that his death was a great loss to the future of Bugatti.

In 1940, the occupying Germans seized the Bugatti factory at Molsheim, conveniently near the German border. Ettore was paid some compensation, which he used in 1942 to acquire the La Licorne works in the Paris industrial suburb of Courbevoie. Though on its last legs, La Licorne was still producing cars. In his own workshops near the Porte Maillot, Bugatti kept busy during the German occupation by developing new prototypes with the help of engineers Noël Domboy and Antonio Pichetto.

At the first post-war Salon in 1946, Bugatti startled the world by unveiling the fruits of his labors, a supercharged, twin-cam, 16-valve, 4-cylinder displacing only 370-cc. He said he had used a motorcycle for secret trials of this, his Type 68, designed to rev to 12,000 rpm and already delivering 48 bhp at 8,000 rpm. His future program, Le Patron declared, was “a Grand Sport de luxe with an engine of 4.0 liters capacity” as well as “a Royale, but much lighter than the previous Bugatti Royale. These cars will only be manufactured in small numbers.”

As well Bugatti presented a new Type 73 family of four-cylinder, 1.5-liter engines, all supercharged, a twin-cam for racing and single-cam for the street. A Pourtout-bodied coupe powered by the Roots-blown single-cam was a centerpiece of the Bugatti stand at the 1947 Paris Salon. The mood on the stand was gloomy, however, for Ettore Bugatti had died on August 21st, only weeks before the Salon’s opening at the beginning of October. Suffering a cerebral paralysis, he’d been bedridden at his Paris flat for several months. His loyal aides brought the Type 73 to the stand in Bugatti’s memory.

It is unlikely that Bugatti had been aware that on June 11th, after much to-ing and fro-ing, a judicial tribunal in Colmar decided that his services to the nation justified the return to him of his factory at Molsheim. But it was in terrible chaos. Bugatti’s survivors faced difficult decisions. At heart, wrote Ettore’s biographer W. F. Bradley, “The Bugatti family decided that the life work of ‘Le Patron’ should not die.”

While Bugatti’s youngest son Roland was interested in the business and knowledgeable about it, he was obliged to live in the south of France for the sake of his health. Much would depend on the view taken by Bugatti’s widow, his young second wife, who had inherited half his assets. She in turn relied on the guidance of her new husband, wealthy paper manufacturer René Bolloré. A connoisseur of fine cars, Bolloré drove a Silver Wraith Rolls-Royce and Aston Martin DB2, but his judgement as a businessman would determine the future of Bugatti.

In December of 1949, René Bolloré sold the La Licorne facility to Renault. He also parted with a boat yard that had been part of the Bugatti empire. It remained for him to make a decision about Molsheim. The works there was in depressing disarray. Its occupants had done their best to keep it from being useful to the Allies, overturning and wrecking machine tools and dynamiting its structures and offices. However, under the direction of Pierre Marco, a Bugatti man for three decades, returning workmen from the surrounding area restored order. The exceptional skills of its 130-strong staff were Molsheim’s most important assets.

Down-to-earth and practical, former racing driver Pierre Marco took in vehicle repairs and servicing, looking after the Bugatti-powered railcars that were still running in France. He also began subcontract manufacture of components for Hispano-Suiza and others, ultimately producing complete engines for tank destroyers. Thus, by the time René Bolloré visited it, the historic plant was not only presentable but also humming with activity. The paper tycoon arrived with the intention of shutting Molsheim down, but Marco and Domboy won him around. “We can not only survive,” they told him, “but also resume the manufacture of cars.”

Not for Marco the grand dreams of Le Patron. Between the wars the prudent manager was in fact often pitted against Bugatti in the internal wrangles over allocation of resources. Ettore’s legendary profligacy was one of the reasons why the company had been on the brink of bankruptcy in 1939. In deference to René Bolloré, Marco would nurture hopes for a 1.5-liter car, son of the Type 73, but his main emphasis was on a new version of the creation of Jean Bugatti that had been so successful before the war, the Type 57.

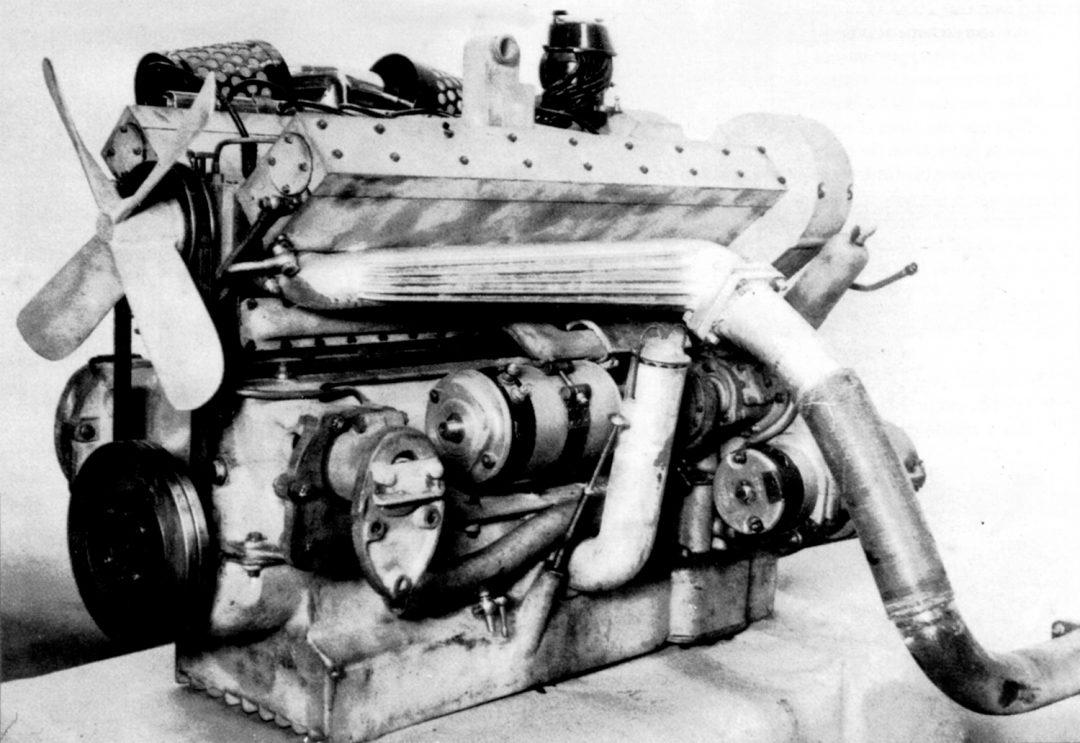

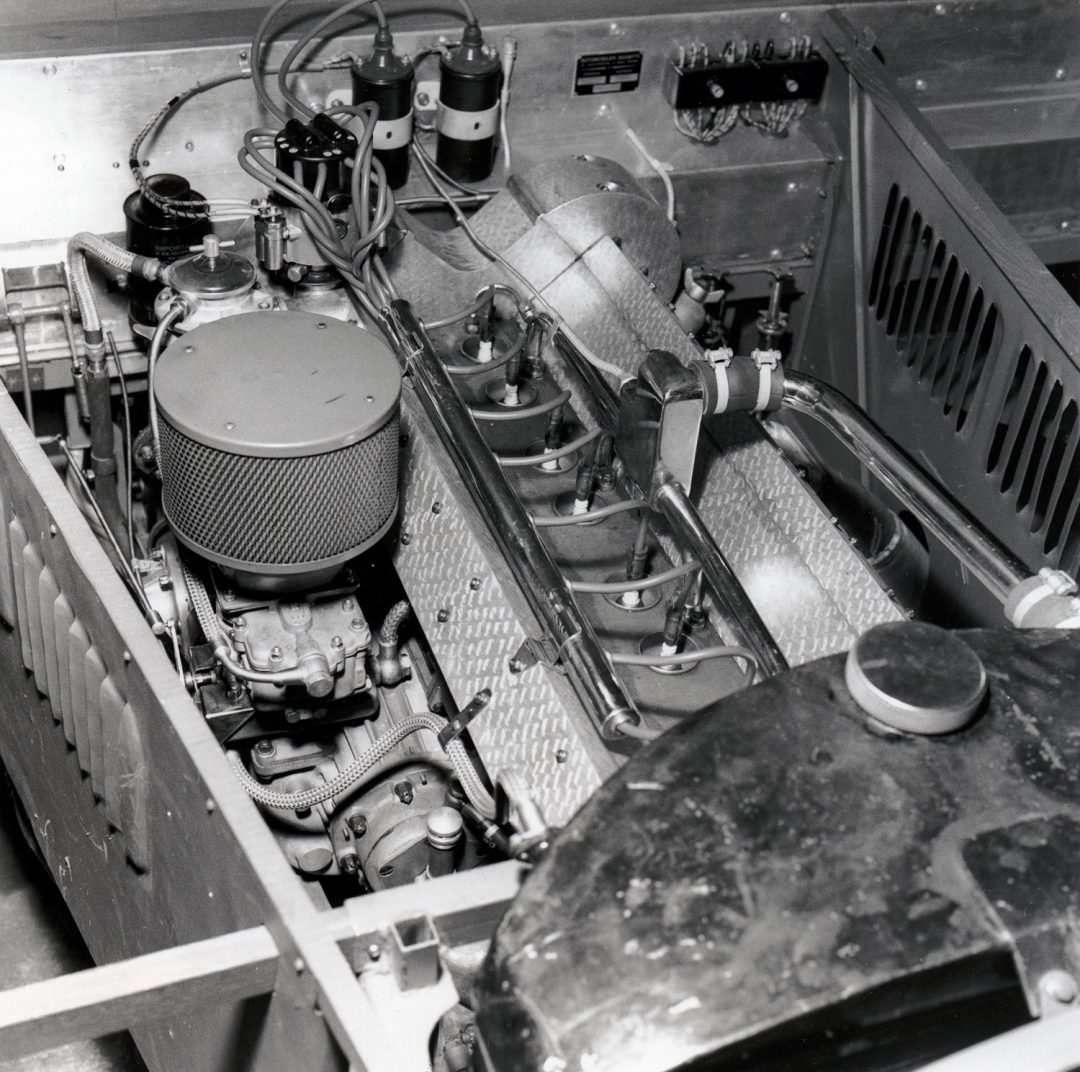

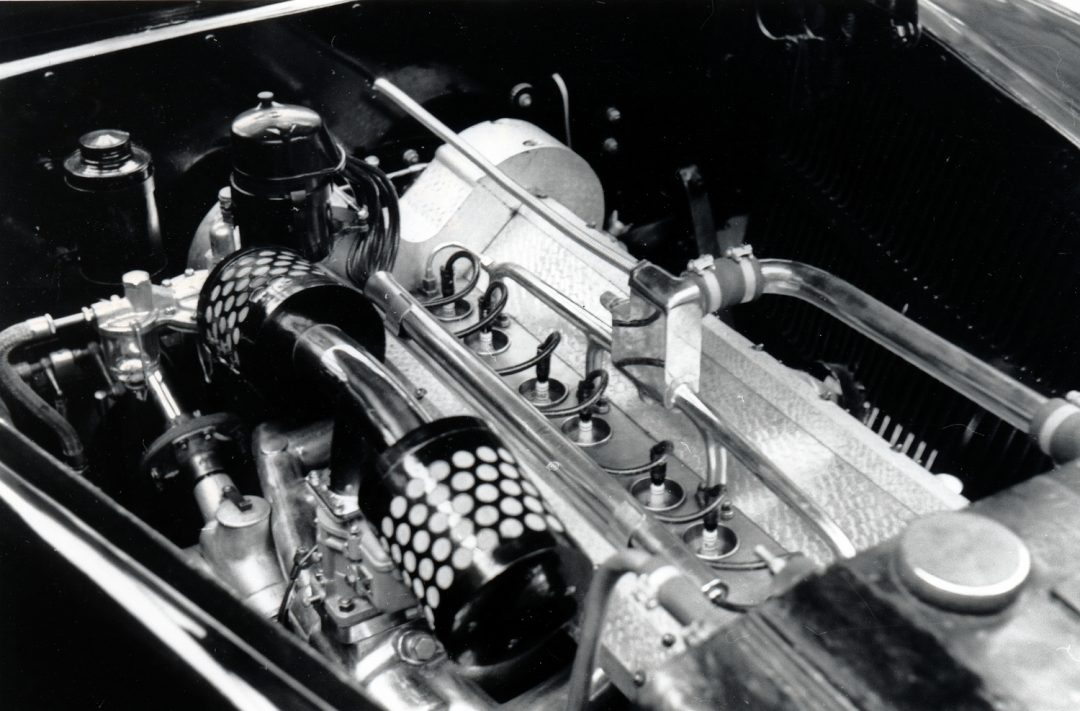

With eight cylinders inline in a Bugatti tradition dating from 1918, the Type 57 measured 72 x 100-mm for 3,257-cc. It had a one-piece cast-iron combined head and cylinder block, which was deeply spigoted into an aluminum crankcase in traditional Molsheim style. Attached to the head were twin aluminum camboxes holding valves at a 94-degree angle. Valve gear was by short and light pivoted finger followers.

The camshaft drive was at the rear of the engine, by a train of helical gears. With such gear trains being notoriously noisy, the large pinion at the end of each cam was made of a Tufnol composite to help silence the drive. Straddling the crankshaft’s drive gear were two main bearings, giving the eight a total of six mains instead of its nominal five. All bearings were plain, with lubrication from a deep squared-off wet sump. Inlet manifolding was on the engine’s right side, fed by an updraft carburetor, while finned exhaust manifolding on the left led to an outlet at the front of the engine.

The normal Type 57 of the 1930s developed 135 bhp at 5,000 rpm. From 1936 a supercharged version was available that delivered 170 bhp, while a dry-sump semi-racing derivative produced 200 bhp. A high-compression variant of the unblown engine was teased up to 170 bhp with the help of magneto instead of coil ignition.

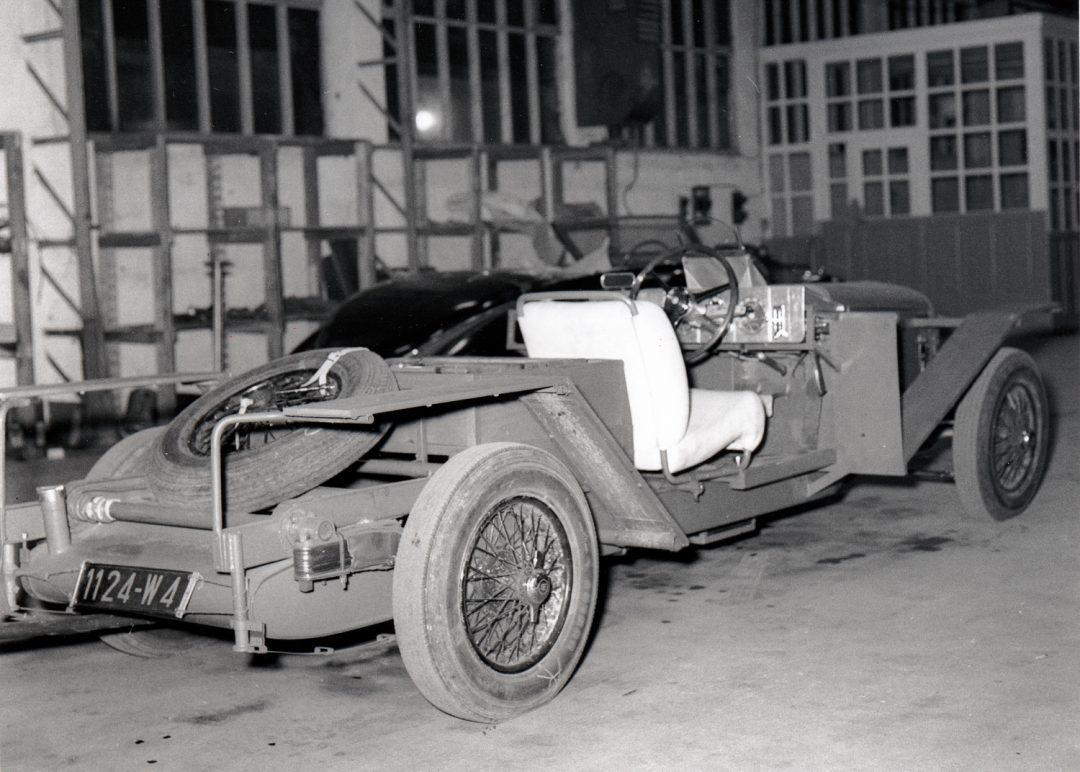

With this kind of specification the Type 57 remained a high-performance car to reckon with in the first years after the war. Thus, a handful of existing Type 57s were rebodied by their owners in a more modern idiom. One was a supercharged chassis that belonged from new to Prince Louis Napoleon, pretender to the throne of France. In Lausanne, after the war, it was bodied by the Swiss arm of Ghia as a handsome dark-green grand-touring coupe. Its vertical grille echoing the traditional horseshoe shape, it made its debut at the 1952 Geneva Salon.

Less is known about the French coachbuilder of a cabriolet on another Type 57 chassis, also supercharged, in the 1950s. He made a good-looking job on a 1938 Bugatti, again with a vertical grille that gave a Jaguar-like frontal aspect. Like all the Type 57 chassis it retained its right-hand drive. Another Type 57 received a blocky coupe body while in 1953 Italy’s Ghia clothed a supercharged 1937 chassis as a sports two-seater.

With new generations of Bugatti owners after the war seeming eager to drive this ultimate Bugatti road car in modernized form, the Type 57 offered a promising foundation for Pierre Marco’s post-war model. Starting work early in 1950 on the Type 101—as it was named to mark a new beginning—he took few chances.

A sign of his conservatism was Marco’s rejection of an improvement that Jean Bugatti had planned for his experimental Type 64 of 1939. To reduce both cost and noise Jean replaced the cam-drive gears with a double-roller chain, still at the rear of the engine. Though an obviously sensible step, this was spurned by Marco as being insufficiently proven.

Jean’s Type 64 had a more modern downdraft carburetor; this was adopted for the Type 101 in the form of a twin-throat Weber 36 DCF. New exhaust manifolding had the downpipe at the rear of the engine instead of at the front. With a 6.8:1 compression ratio the base power unit equaled the pre-war rating at 135 bhp at 5,500 rpm.

For the ultimate in output compression was cut back to 6.5:1 to accommodate a Roots-type supercharger, with which power went up to 190 bhp at 5,400 rpm and 200-plus with a modest increase in boost pressure. This gave the post-war Bugatti the highest horsepower of any European road car of its time, also rivalling the contemporary output of such American V8s as those of Chrysler and Cadillac.

While Type 57s had four-speed transmissions, a new five-speed box with an overdrive top was developed for the Type 101. Although to be fed by the twin-plate clutch that had been introduced before the war to cope with power increases, none of these boxes ever appeared.

Thus, most of the 101s were fitted with a completely new feature, a Cotal electro-magnetic transmission. Still coupled with a twin-disc clutch, this used large-diameter magnetic clutches to control two planetary gear trains that gave four forward speeds. Favored by several French luxury-car makers, the Cotal had been planned for Bugatti’s 1940 models. Its availability satisfied a particular request of René Bolloré.

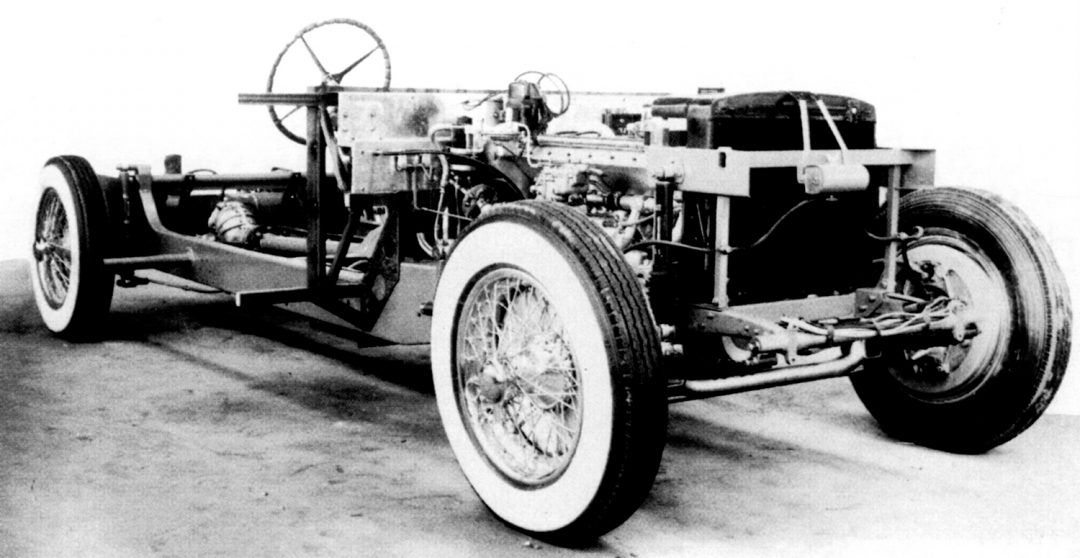

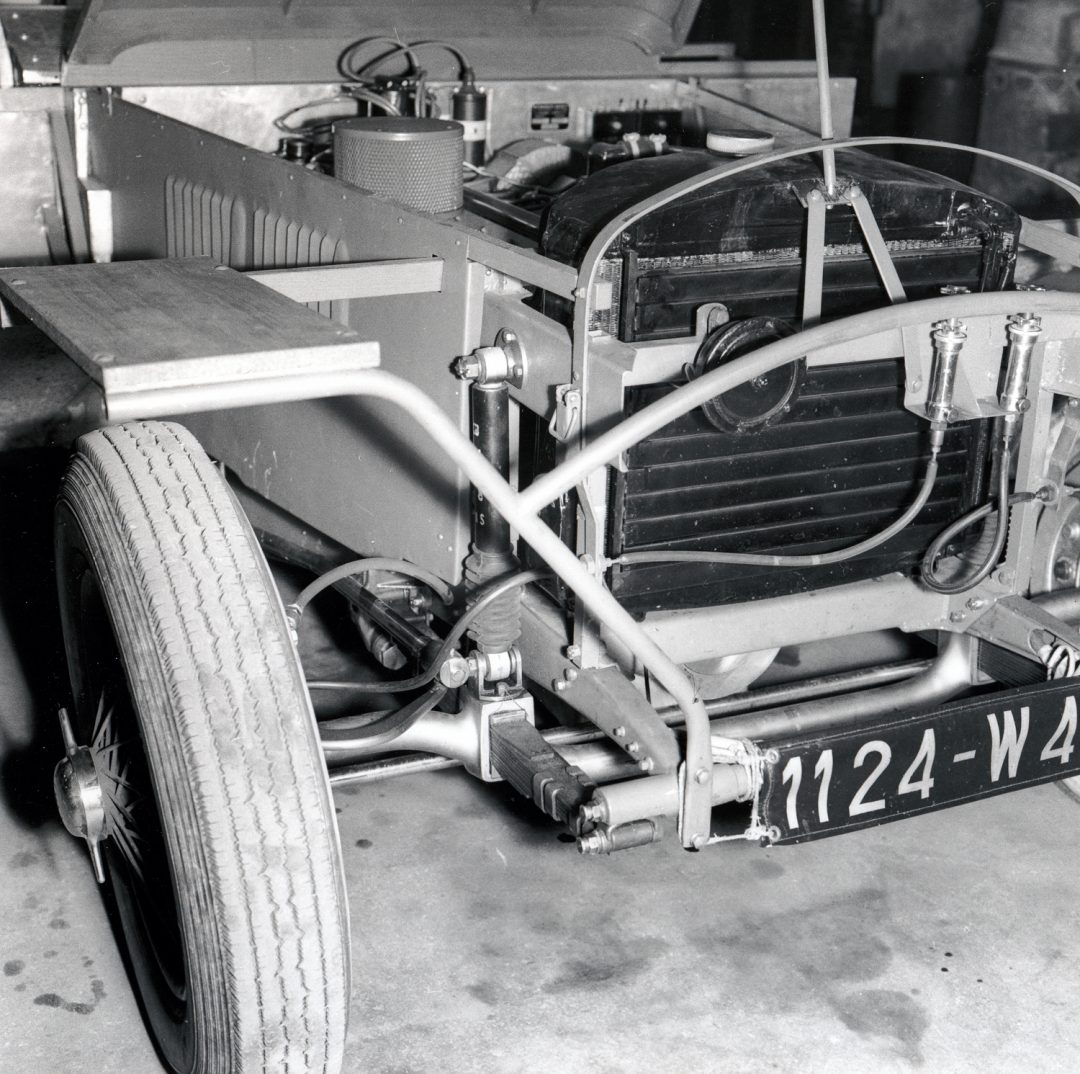

With conventional touring-car bodywork on Marco’s agenda, he used the standard Type 57 frame with its wheelbase of 129.9 inches instead of the special low-slung frame with 117.3-inch wheelbase developed for the pre-war sports Bugattis. Its channel-section side members ran straight from the firewall back and kicked up over the rear axle. Robust crossmembers ensured stiffness, especially necessary after the design was modified in 1938 to provide rubber mounting of the engine. Previously, in time-honored tradition, the straight-eight had been bolted to the frame to add rigidity.

Tradition was also observed in the rear suspension, with a live axle controlled by a long torque arm reaching forward to the rear of the gearbox. Springing was by quarter-elliptic leafs reaching forward to the axle from the rear of the frame. Damping was by special Allinquant tubular shock absorbers at front and rear as used on the Type 57 from 1938.

To the dismay of the shade of Jean Bugatti, the Type 101’s front suspension was by solid axle as well. Jean’s first scheme for the Type 57, in 1932, showed independent front springing by twin transverse leafs. This was worked out in detail by Antonio Pichetto, who designed similar front suspension for Bugatti’s four-wheel-drive Type 53 for hill-climbing. When he got wind of this apostasy, however, Ettore decreed that the new model would have a solid front axle, and that would be that. Only the Type 57 prototype had independent springing.

Here again, Pierre Marco rejected such novelties in favor of the proven Type 57 solid-axle front end, even though independent front suspension was all but universal on post-war models. In compensation the Bugatti axle was a thing of beauty, with a tubular center section and built-in boxes, which held the centers of the semi-elliptic leaf springs. On the left-hand side a radius rod relieved the springs of some of the braking torque reaction.

Hydraulic brakes, which at Molsheim dated from 1938, were used on the Type 101. With Lockheed mechanisms they were of powerful two-leading-shoe design at the front. According to Bugatti independent circuits were provided to isolate any cause of failure. Finned brake drums contained eight-shoe Lockheed brakes inside wire wheels carrying 6.00 x 17 white-sidewall tires. This was an advance in both grip and ride comfort from the 5.50 x 18 tires used before the war.

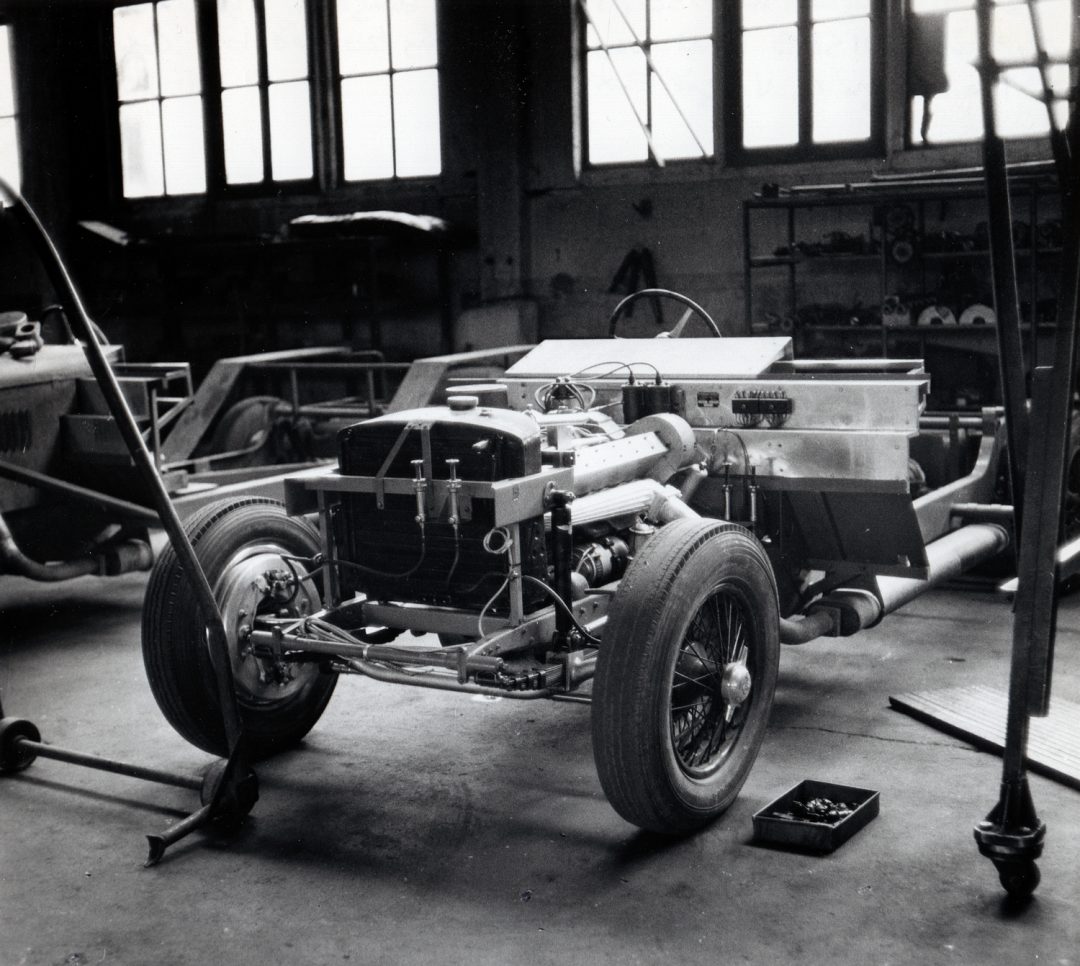

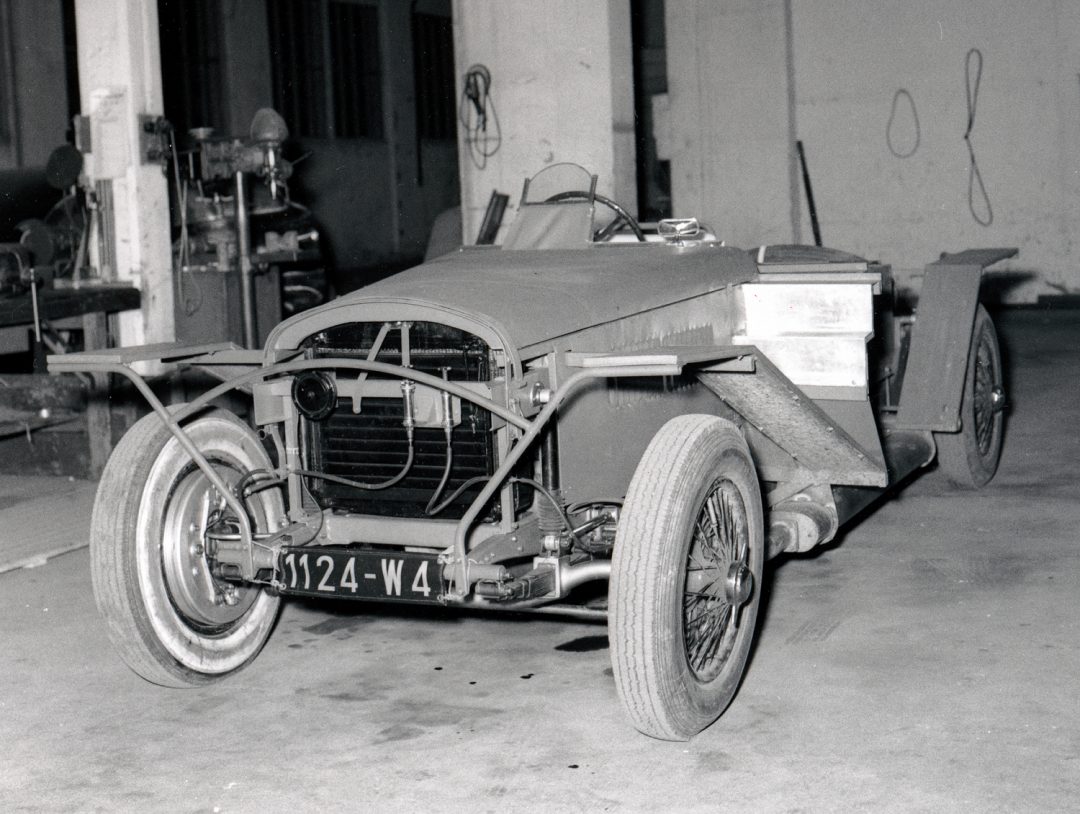

On this foundation Pierre Marco’s engineers planned the Type 101, testing its new features—such as a conventional radiator with temperature-controlling shutters—with new front-end panels grafted onto a 1935 Type 57 chassis. The definitive first Type 101, chassis 101500, had a three-box four-door saloon body built in Alsace. With a long bonnet and front wings faired back into the front doors, it was based on a scale model produced in May of 1950 by young stylist Louis Lepoix. A distinctive feature was his mounting of its free-standing headlamps in coves flanking a sloped-back Bugatti radiator.

With its body completed in the autumn of 1950, 101500 was tested through the following winter. Though the car was seen here and there, no official announcement was made of impending manufacture until September 1, 1951 when L’Auto Journalrevealed that new Bugattis would be produced. At Molsheim, it joyfully reported, “snow has given way to sunshine, silence to the noise of the machines and the air of sadness to smiles. During the last six months the Bugatti Works have been rebuilt and a festive air pervades every brick, every piece of metal plate, in fact everything.”

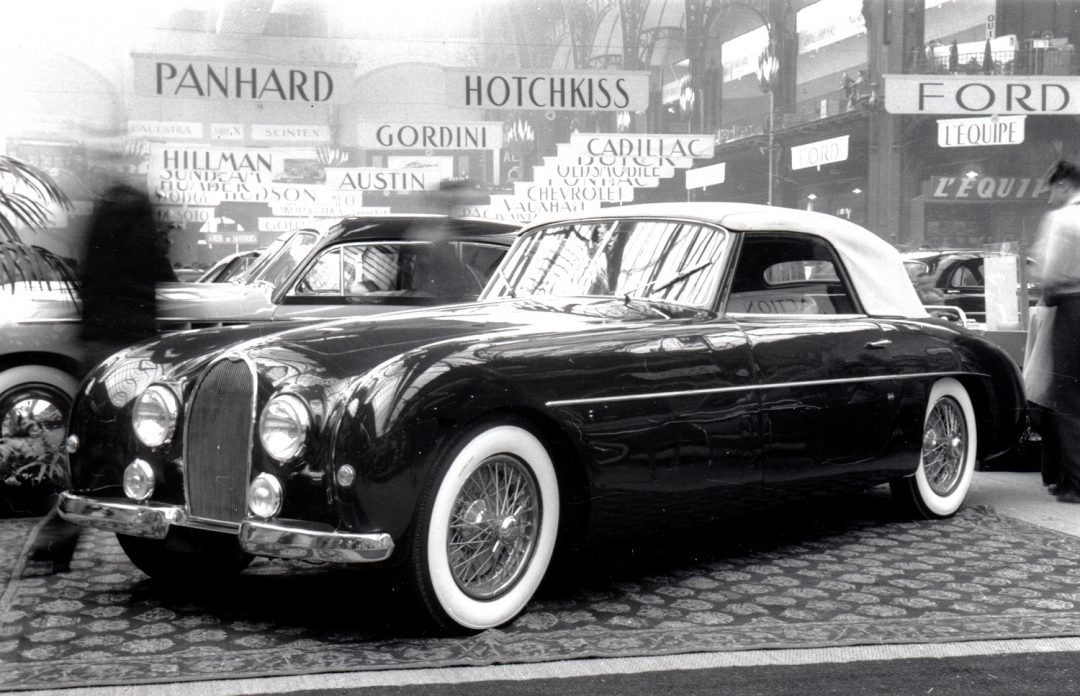

For coachwork on the new model’s right-hand-drive chassis Pierre Marco turned to an old Bugatti ally, Gangloff in Alsace’s Colmar, 35 miles south of Molsheim. Run from 1919 by Georges Gangloff, it erected magnificent coupes and cabriolets on the Type 57 chassis. For the Type 101, Gangloff produced all-enveloping bodies that were at the cutting edge of the state of the car-design art.

With designs that were to prove highly influential, in 1947 Kaiser and Frazer were the first to show that complete sublimation of the wings into the main body shape could be a viable aesthetic for a volume-production car. Europeans were reluctant to follow the same road, Borgward with its 1500 Hansa being one of the first. At the 1951 Paris Salon, the only other French makers to follow suit were Ford of France with its Turin-influenced Comète, Simca with its Aronde and Letourneau et Marchand with their body for the latest Delahaye.

While acknowledging the avant-garde concept of the Type 101, it must be said that Gangloff’s interpretation was notable more for its stolidity than for any sense of fleetness. Curved windscreens, then increasingly common, helped somewhat. An imposition on the designers was the decision to put the spare wheel inside the right front wing, which effectively mandated its height while, to be sure, adding trunk space. A raised bonnet panel rested uneasily atop the front sheet metal while a horseshoe-shaped grille was flanked by close-set headlamps. Air vents like the feathers of an arrow decorated the wings.

While the catalogue for the Type 101 showed both two-door and four-door models, only the latter were displayed in Paris. The coupe’s serial number of 57454 betrayed that Molsheim had used a Type 57 frame that dated from 1937 as its basis. It had a supercharged engine. With 101501 the unblown cabriolet was the first in the new-model series after the prototype. Chassis 101502 went to the Paris suburb of Courbevoie where Guillore bodied it as a two-door sedan with separate fenders, using coachwork it had in fact originally fashioned for a Delahaye.

By the time the Geneva Salon opened in March 1952, Gangloff responded to criticism of its initial effort with improvements to both coupe and cabriolet. Replacing the side vents was a trim piece running to the rear. The hood was now smoothly faired into the front metalwork, the revised design making room for a grille that was significantly higher and wider than the original, which had not passed enough cooling air. Headlamps were raised, making space below them for air inlets. A retrograde step was the appearance of a small strip down the center of the windshield.

This, said Bugatti, was the definitive design for production. Chassis 101503 was bodied as a cabriolet by Gangloff for the 1952 Paris Salon. It had all the latest refinements including the larger grille, plus a windscreen that was notably higher than those of the first two cars. Its price mooted at the Salon was “around three million francs”, the equivalent of $7,500 at a time when a Cadillac convertible cost $4,163. If this were not deterrent enough, the French authorities suddenly imposed annual road taxes of triple the usual amount on cars rated at more than 16 CV by the French system; unhappily the Type 101 was 17 CV.

Such French luxury-car makers as Delahaye, Talbot-Lago and Delage were hit hard by the new taxes; this was the beginning of the end for them. They were also the final straw for the Type 101. Nineteen fifty-two was its last appearance at a Paris Salon. Of the six new chassis that had been laid down, only three were bodied according to plan and only two of those by “official” coachbuilder Gangloff. One chassis, 101505, never did receive a body and may be viewed at the Musée Nationale de l’Automobile at Mulhouse together with 57454, 101500 and 101503.

René Bolloré is thought to have commissioned the body for supercharged chassis 101504. In that hub of French coachbuilding, Courbevoie, he asked van Antem to style a two-seat coupe that would bespeak Bugatti’s legendary speed and sportiness. The result, in 1954, was a long-bonnet machine with perforated guards under the sills at both sides, the one on the left concealing an external exhaust pipe. A panoramic effect was achieved by making its windscreen in four parts. After a lengthy sojourn in Bill Harrah’s collection this Type 101 is again in circulation in the classic-car world.

The last chassis, supercharged 101506 with a five-speed gearbox, was still at Molsheim in 1961. It was certainly the chassis that Madame J. C. Gomet had in mind in November of 1962 when she commissioned Giovanni Michelotti to propose a design for it. Probably to be built by Vignale, this was a coupe on a shortened wheelbase. That wasn’t to be the fate of this Type 101, however.

In 1961, chassis 101506 was acquired from the Bugatti estate by an American, E. Allen Henderson. Resident in Perth Amboy, New Jersey, Henderson enjoyed a visit one day from André Surmain, restaurateur and collector and his friend L. Scott Bailey, publisher of Automobile Quarterly. They had come to look over Henderson’s Bugattis, some of which the collector was preparing to sell. Inside a large barn they found no fewer than 14 unrestored Bugattis including an unbodied chassis.

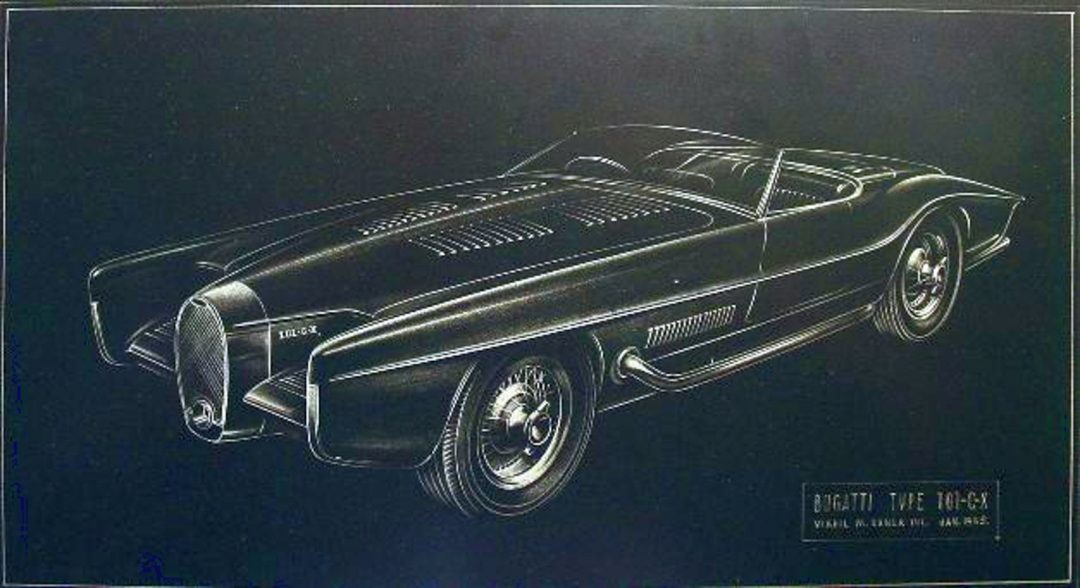

News of these events reached former Chrysler chief stylist Virgil Exner and his son Virgil, Jr. For a “revival cars” article in Esquire,Exner had speculated about the way a modern Bugatti might look; here was his chance to realize that dream in the metal. With Bailey’s intervention, the naked chassis was acquired by Exner for $2,500 and towed back to Birmingham, Michigan, in a blizzard by the younger Exner.

In preparation to clothe the chassis with a sports-car body Virgil, Jr. and his friend Mike Cleary shortened its frame by 18 inches to 112 inches. Assisting with the Bugatti’s engineering were colleagues Paul Farago and Dale Cosper. As the car had a manual shift, it is likely to be fitted with a Type 57 four-speed transmission.

Working strictly to the designs and one-eighth-scale model prepared by Exner and his son, Ghia built the body. It covered the construction costs and all shipping as well, in lieu of paying the more than $27,000 in consultancy fees that it owed to the Exners.

The result, painted midnight blue with ivory wire wheels, was revealed at the Turin Salon in November of 1965. The Exner styling was a tour de force of engineering, as well as styling in that it achieved a low-slung sports-car design on a chassis that was not at all intended for such bodywork. It proudly thrust forward an ovoid Bugatti radiator shell between cooling-air intakes in coves that housed its rectangular headlamps.

If Exner’s styling of 101506 was “somewhat amazing”, in the words of Type 57 expert Barrie Price, it was in this respect at least entirely in the tradition of many previous Bugattis. With its motorboat-style veed windscreen and swooping fender lines the 101C-X — as it was named — bespoke speed and luxury. Swathes of louvers on its hood and flanks evoked the character of racing Bugattis. Although Virgil Exner, Jr.’s sketches and model showed an outside exhaust, this was omitted on the finished car.

Virgil Exner deserved plaudits for his courage and daring in clothing the newest existing Bugatti chassis with a new body style instead of aping the work—admittedly magnificent—of Jean Bugatti by making just another replica of a pre-war Type 57. Barrie Price commended Exner for a radiator design that was “the most traditional interpretation of the Bugatti horseshoe seen on any Type 101”.

From the perspective of more than 50 years later, the Exner 101C-X may be seen as the quintessence of Pierre Marco’s brave attempt to revive the marque. By showing it at Turin, Virgil Exner had hoped to spark interest in a production series, but this didn’t mature. After driving it for some 1,000 miles, he sold it to collector Thomas Barrett III, in 1969. This unique Bugatti 101 was later acquired by General William Lyons.

The Type 101 was not Marco’s last throw of the dice. He had ideas for other future Bugattis including a Grand Prix model and a 1.5-liter sports car, the “Ettorette,” but these were not realizable. By 1962, Pierre Marco had retired and Noël Domboy was in charge of the Molsheim works when the Type 451 project was launched to build “a Grand Sport de luxe” on the lines that Ettore had proposed after the war.

Planned for this new Bugatti was a 60-degree V-12 engine of 4,464-cc (80 x 74 mm) with the potential for 300 horsepower. Suspension was to be all-independent by coil-spring struts, with its clutch and transaxle grouped at the rear, in the manner of the Lancia Aurelia. First components for the space-framed Type 451 were being made when, in July 1963, the works and its assets were taken over by Hispano-Suiza—not for its cars, but for its capacity to help it fulfil defense contracts.

Though car production at Molsheim ended, the dream of a Bugatti V-12—one of the few engine types that Ettore had never built—did not easily die. A twelve was chosen for the revival of the Bugatti marque in Italy in 1991. Had Messrs. Bolloré and Marco not accepted the risk of creating the Type 101 to sustain the Bugatti legend, there might have been no marque to revive. It was the vital link between the great pre-war cars and the awesome record-setting Bugatti Veyron and Chiron of the 21st Century.