We called it the “Bruce and Denny Show,” and it was total dominance of the Can-Am Championship by McLaren Cars from 1967 to 1971, during which they won 43 of the series’ 71 races, 23 of them consecutively. It was an astounding performance in which New Zealander Bruce McLaren won the championships of 1967 and 1969, his countryman and teammate Denny Hulme in 1968 and 1970 and American Peter Revson in 1971, all in McLaren cars.

It was a crusade that turned out to be the even-tempered Bruce’s downfall, because he was killed in mid-1970 when he was only 32 years old, testing his new Can-Am car at Britain’s Goodwood circuit. Not before, however, he had won four Formula One World Championship Grands Prix, a tally that never really reflected his single-seater ability, two Can-Am titles and nine races, as well as the 24 Hours of Le Mans, and he was poised to make a full frontal attack on the Indianapolis 500.

Bruce’s dad was a successful garage owner in the Auckland suburb of Remuera in New Zealand, where the lad used to hang around the workshop soaking up the atmosphere before a run-in with Perthes, a disease that affected his hip and left his left leg shorter than his right. An unpleasant two years in traction was a help, not a cure, because Bruce was left with a noticeable limp. But that didn’t stop him from winning the 1958 Driver to Europe scheme run by the New Zealand International Grand Prix Association after scoring good results in his own Cooper F2 car.

So Bruce made his scholarship trip to Britain, where his F2 performances caught Jack Brabham’s eye and that got the youngster a ride alongside Black Jack in the works Cooper team. Bruce made his mark pretty soon and won the USGP at Sebring. He was the youngest Grand Prix winner at the time, as he was only 20 years nine months and 14 days old. Jack came 4th in the same race and that was enough to secure him his first world title.

The 1960 season was Bruce’s best in F1 as he finished 2nd to Jack in the F1 World Championship, mainly by quietly supporting the Australian and placing well. When Brabham retired from the Grand Prix of Argentina with gearbox trouble, Bruce grabbed the chance and went for it, beating an impressive field of Ferraris, Lotuses, BRMs and Maseratis to win.

With the departure of Jack Brabham to form his own team at the end of 1961, the young New Zealander took over as Cooper’s team leader, but that was the year when the little Surbiton company’s performance began to wane. There were no F1 championship victories for Bruce and Cooper in 1962, just top-six placings that would only earn him equal 7th in the championship table with a young Scot called Jim Clark.

McLaren did manage to put his works Cooper-Climax on the front row of the grid for the 1962 Monaco GP with Graham Hill (BRM) and Jim Clark (Lotus-Climax). Graham’s mastery of the Monte Carlo circuit soon began to show, and by lap 56 of a scheduled 100, the Briton was 48 seconds ahead of Bruce. Then Hill’s oil pressure began dropping and he was forced to let McLaren through on lap 93 to win from the Ferraris of a hard-charging Phil Hill and Lorenzo Bandini.

Bruce was fairly pissed off when the penny pinching Charles Cooper refused to build two cars for him to race in the 1963-’64 Tasman Cup Championship. So McLaren, who stayed on at Cooper for a total of seven years, built the cars himself and raced them down under as Bruce McLaren Motor Racing entries.

The young New Zealander won the 1964 Tasman Cup Championship in a Cooper T70-Climax with three consecutive victories at Pukekohe, Wigram and Teretonga Park, but his American team-mate Tim Mayer crashed and died while practicing for the last race in the series at Longford, Tasmania. Qualified lawyer Teddy Mayer, who had been managing his late brother’s career, joined forces with Bruce and brought money and more brain power to the fledgling McLaren team.

McLaren left Cooper at the end of 1965 and rolled out his own F1 team, an all-New Zealand driving affair with Chris Amon as his number two. That didn’t last long, because Chris was soon head-hunted by Ferrari to drive for Maranello. Before he left, though, the two crewed one of Shelby American’s Ford GT40s in the 1966 24 Hours of Le Mans, the other driven by Ken Miles/Denny Hulme: a third was entered by Holman and Moody/Essex Wire Corp. for Ronnie Bucknum/Dick Hutcherson.

The fairly serious Ferrari P3 works cars and a gaggle of private entrants gradually dropped out with various ills as the 24 hours wore on, the last to depart the NART P3 of Pedro Rodriguez/Richie Ginther, which went out with overheating problems. So the race looked like it was going to be won by Ford, a first for an American car. Just before the end, Ford decided to stage a photo op: the Miles/Hulme car was in the lead, the McLaren/Amon GT40 2nd: the 3rd placed Bucknum/Hutcherson car, which was 12 laps down, was allowed to catch up for a three-abreast victorious Ford finish across the line at Le Mans, an incredible sight. Miles/Hulme were thought to have won the photo finish, but after the ACO examined the pictures they declared McLaren/Amon the winners. It was the closest finish in Le Mans history, and one about which Ken and Denny must have felt sore. Regardless, it was followed in February 1967 by the famous 24 Hours of Daytona finish in which three Ferraris sailed across the Florida finish line three abreast!

McLaren Motor Racing was on the threshold of something really great as Bruce and Chris became two of the earliest competitors in Can-Am in 1966, driving the McLaren M1A and then the M1B. The cars were not exactly earth-shattering performers, so Bruce came back with his Chevrolet-powered M6A in 1967 and Chris’ spot was taken over by another New Zealander, Denny Hulme. That was when the curtain went up on the Bruce and Denny Show.

Hulme won the first three Can-Am races in the McLaren M6A-Chevrolet, but Bruce stepped in and took both the Laguna Seca and Riverside rounds which, with his better placings, made him the 1967 Can-Am Champion.

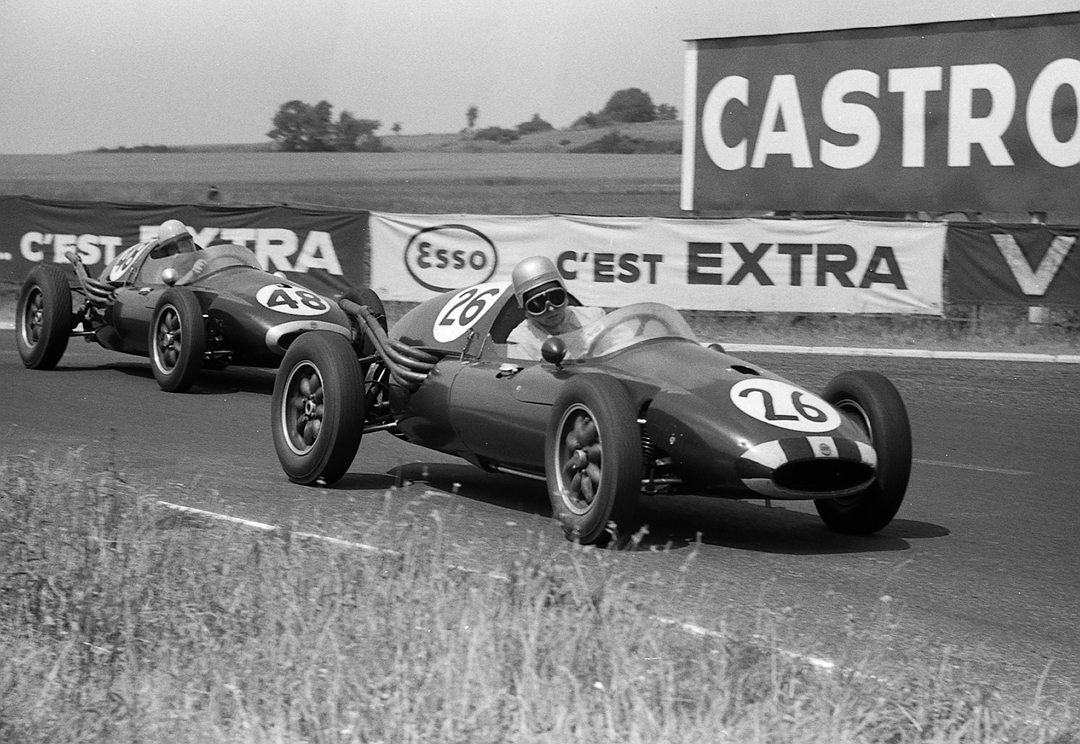

Photo: Roger Dixon

By then, the fans had well and truly caught the big-banger bug and were packing the circuits by September 1, 1968, when the McLaren M6As and M8As took a hold of the series and didn’t let go of it for two whole years. They won 23 races right off the bat, a non-stop victory rampage; 11 of them went to Denny, seven to Bruce, two to Dan Gurney, one to Mark Donohue, another to Canadian John Cannon and a single victory to Peter Gethin before Tony Dean brought a temporary end to all that in a Porsche 908 by winning Road Atlanta on September 13, 1970. It was only a brief respite, though, because the McLarens were back on the warpath at Brainerd on two weeks later, when they began another 15 Can-Am victory run before Porsche became top dog with the fabled 917.

The McLaren F1 effort continued into 1969 with Bruce and Denny scoring many top six placings but no more victories. Their efforts took Bruce to 3rd in the World Drivers Championship table with 26 points, miles away from title winner Jackie Stewart and his 63. The team made 4th in the constructors title chase, but that, too, was a long way from victorious Matra-Ford.

Bruce was down to drive Carroll Shelby’s turbine car at Indianapolis in 1968, but the American withdrew the jet-powered monster because he considered it too powerful. McLaren still had his sights set on the Brickyard, however, and in mid-’69 got designer Gordon Coppuck to create the turbocharged M15 based on the team’s all-conquering Can-Am car. Testing confirmed the car could be competitive, but during a practice session, the fuel filler cap snapped open and covered tester Denny Hulme’s hands and the car itself with blazing methanol. That put him out of racing and meant he could not drive one of the three M15s readied for Indy; the remaining two were campaigned by Carl Williams and Peter Revson, who covered 197 and 87 of the 200 laps, respectively. The M15 won Indy’s coveted Schwitzer Award for engineering excellence.

Then tragedy struck. Bruce was killed testing his new M8D Can-Am contender at Goodwood on June 2, 1970. After the shock and horror of losing their quiet, charismatic, highly successful boss, the team decided the best tribute they could pay him was to continue, which they did in spectacular fashion in F1, Can-Am and Indy, where Mark Donohue won the 500 in a McLaren in 1972 as did Johnny Rutherford in 1974 and 1976.

Bruce’s achievements were staggering. He was a Grand Prix winner four times over, his cars had become the dominant force in Can-Am and stayed that way for five mind-blowing years and he was about to take Indianapolis by storm. Some said he was thinking of retiring from racing before he died. His business was certainly a success and a road-going version of his M6 Can-Am racer was on the cards: prototypes had already been built.

The McLaren team, however, went on to become one of the greatest in the history of Formula 1, a fitting tribute to its founder.