1940 BMW 328 MM “Berlin-Rome” Touring Roadster

From its inception in 1916 to 1927, the Bayerische Motoren Werke (BMW) built a growing business centered around the design and manufacture of water-cooled aircraft engines and motorcycles. However, in 1928, Deputy Chairman of the Supervisory Board Camillo Castiglione, struck upon the bold move to increase the footprint of the German company by (1) moving into air-cooled aircraft engines by becoming the only licensed German manufacturer for Pratt & Whitney, and (2) entering the automotive marketplace by acquiring an existing automobile manufacturer.

By leveraging the company to the hilt, Castiglione was able to achieve both goals. On the automotive side, BMW ultimately purchased Fahrzeugfabrik Eisenach, which in addition to building military vehicles and bicycles, also produced the Austin Seven, under license in Germany, as the “Dixi 3/15/PS.” On March 22, 1929, the first BMW 3/15PSDA2 rolled off the Berlin-Johanisthal assembly line, with all of 15 hp at its disposal.

While this small, underpowered, somewhat boxy-looking sedan wouldn’t initially suggest motorsport competition, BMW chose to enter a team of them in the 1929 running of the International Alpine Rally. While the 3/15 was not necessarily the fastest car over the many cols of this venerable rally, it did prove to be immensely reliable, resulting in BMW stunning the racing world when it walked away with the coveted Golden Alpine Trophy for best overall team performance. This win marked BMW’s first victory as an automotive manufacturer and would prove to be a foreshadowing of greater things to come.

Over the course of the next five years, various evolutions of the “Dixi” would continue to win races, but by 1933, it was evident to the management at BMW that in order to be competitive on the international stage, they would need a more powerful car. With development dollars extremely limited—as a result of the 1929 stock market crash and its bold expansion gambit—the management at BMW opted to build a 6-cylinder evolution of the 4-cylinder Austin-based engine. The car BMW built to carry this new 6-cylinder engine was called the 303 and marked the first “clean sheet of paper” design for the new manufacturer. The 303 featured a 6-cylinder, 1.2-liter engine breathing through two downdraft carburetors and came in several different body configurations. A more sporting iteration of this new design saw a larger 1.5-liter engine mated to a two-seat roadster body. This new 315/1 roadster was the first BMW capable of breaking the 100-km/h barrier. The 315/1 roadster made its debut in 1934 and, in its first year of competition, it again won the prestigious Alpine Trophy, as well as two 1st-place finishes during the international races at Kesselberg. Bolstered by these results and seeing the advantages that motorsport success was bringing to the company, BMW management committed to a more aggressive motorsport program that targeted the international 2-liter sports car class.

Tasked with heading up the team that would design a new 2-liter sports car was BMW Chief Designer Fritz Fielder. Among Fielder’s many challenges was the fact that, due to continued hard economic times in Germany, there was still little or no development budget for motorsport. As a result, Fielder developed this new 2-seat sports car from the new 326, mid-size luxury car that BMW introduced in 1936. The two-seat roadster version was dubbed the 328, and featured the same basic 2-liter, inline, 6-cylinder engine as the 326, only now fitted with an alloy head that utilized hemispherical combustion chambers and a single, side-mounted camshaft that operated the overhead valves by an ingenious series of rockers and horizontal pushrods. The result was an engine that produced 80 hp housed within a car that weighed in at just 830-kgs and was capable of 150 km/h. In a bold move, BMW chose to debut the new 328 sports car, not at one of the many European motor shows, but at a race, the June 14, 1936, running of the Eifelrennen at the Nürburgring. Driving the new 328 was World Motorcycle Speed Record holder and BMW motorcycle rider Ernst Jakob Henne, who managed to give the 328 a remarkable debut victory in the 2-liter class.

Over the next two years, the 328 raced and won in a wide variety of international events. As time progressed, Fielder and his team were able to coax progressively more and more horsepower from the engine, resulting in it now developing 110 hp. However, new challenges were to be faced. First and foremost was the amount of time and resources now being devoted to the rearmament of Germany under Chancellor Hitler. While resources were being diverted to military build-up, Germany’s new “Fuhrer” was also pushing heavily for German automobile manufacturers to demonstrate Germany’s superiority on the international stage.

One of the ways that Hitler was able to exert his control over the German automotive industry was to consolidate all automotive activities under the banner of a single paramilitary organization. This new body, which would oversee all automotive clubs, training and activities, including domestic and international motorsport, was dubbed the National Socialist Motor Corps (NSKK) and was put under the direction of a military officer named Adolf Hühnlein. Hühnlein reported directly to Hitler and personally oversaw the racing efforts of Auto Union, Mercedes-Benz and BMW from 1934 to 1942. While focusing the efforts of Mercedes and Auto Union on Grand Prix racing, Hühnlein chose to direct BMW’s efforts on long-distance sports car racing.

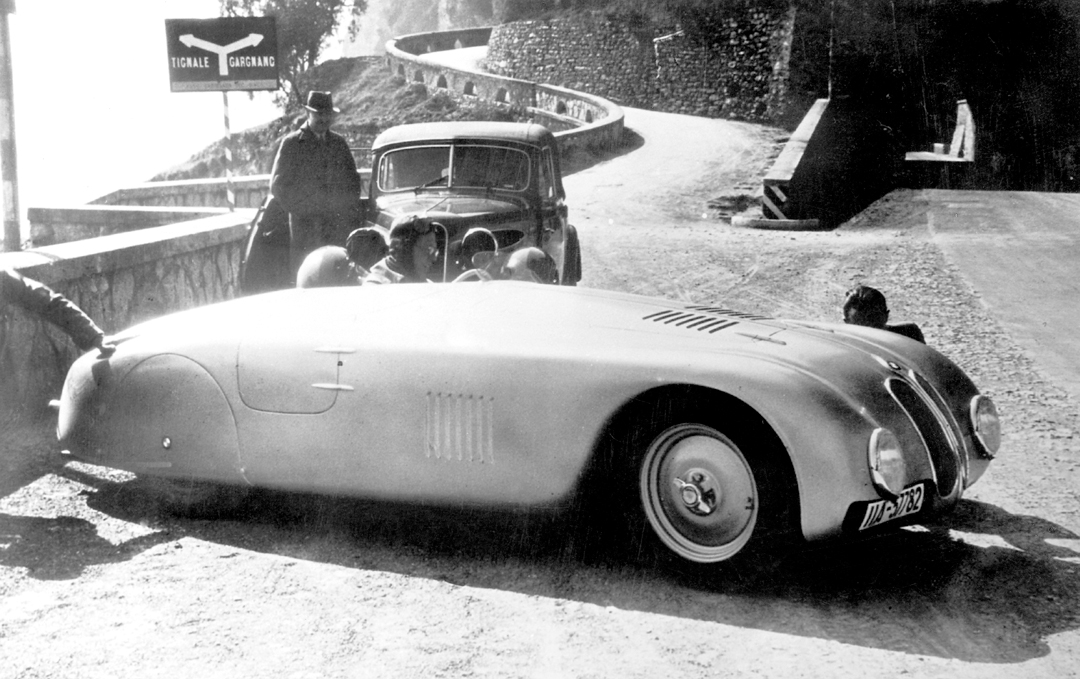

Looking to promote the industrial might of Germany, the Nazi propaganda machine announced that, in 1938, a high-speed race would be held from Berlin to Rome using the new system of “autobahns” and “autostradas” built in each country. Hühnlein determined that this would be an ideal event for BMW to demonstrate their abilities, so he commissioned the manufacturer to produce a high-speed, 2-liter sports car for the event. However, in order for BMW to coax more speed from their existing 328 they would either have to find a way to develop much more horsepower or create cars that were lighter and more aerodynamic. With the rearmament effort taxing their already stretched resources, Fielder and his colleagues chose to increase the 328’s top speed by creating a new, lighter, more aerodynamic variant.

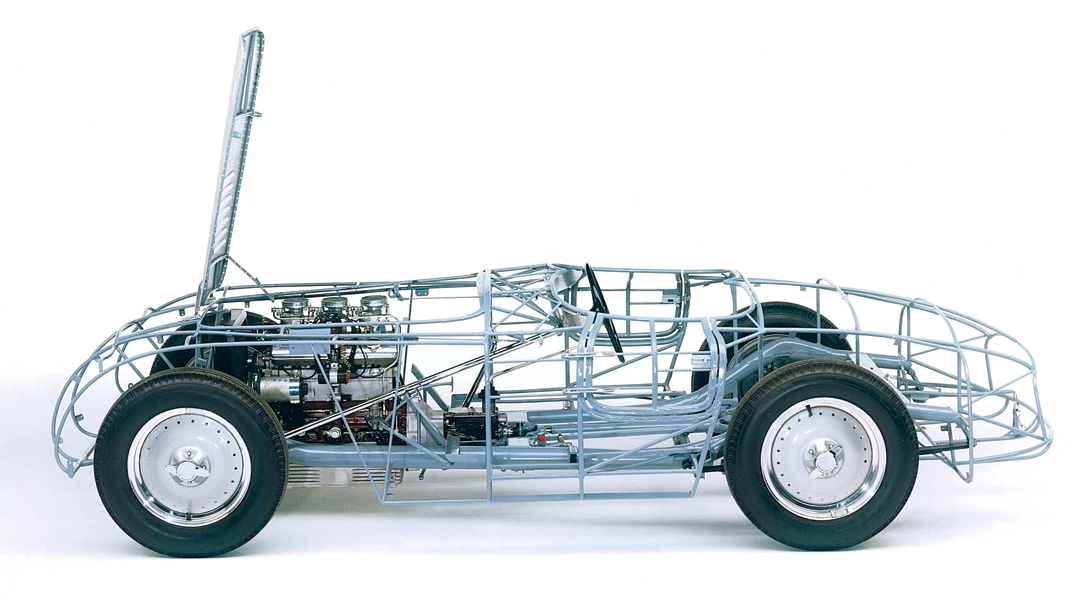

Rather than trying to construct this new bodywork in house, the BMW competition department contracted with Carrozzeria Touring, in Milan, for the creation of a coupe body made of aluminum using Touring’s “Superleggera” construction technique, where the aluminum bodywork was mounted onto a lightweight network of tubes, which were then welded to the underlying frame. Other changes to this new prototype racecar included a modified and lightened frame that mounted the engine and running gear lower than in the normal 328.

While the date for the Berlin–Rome race was being continually pushed back, the NSKK chose to debut the new aerodynamic 328 coupe in the 1939 24 Hours of Le Mans. Management of the Le Mans effort was entrusted to Prince Max zu Schaumberg-Lippe, a high-ranking leader in the NSKK, who not only directed the team but opted to co-drive the new enclosed coupe with co-driver Hans Wencher, while two normal 328 roadsters were to be driven by the teams of Roesel/Heinemann and Briem/Scholz.

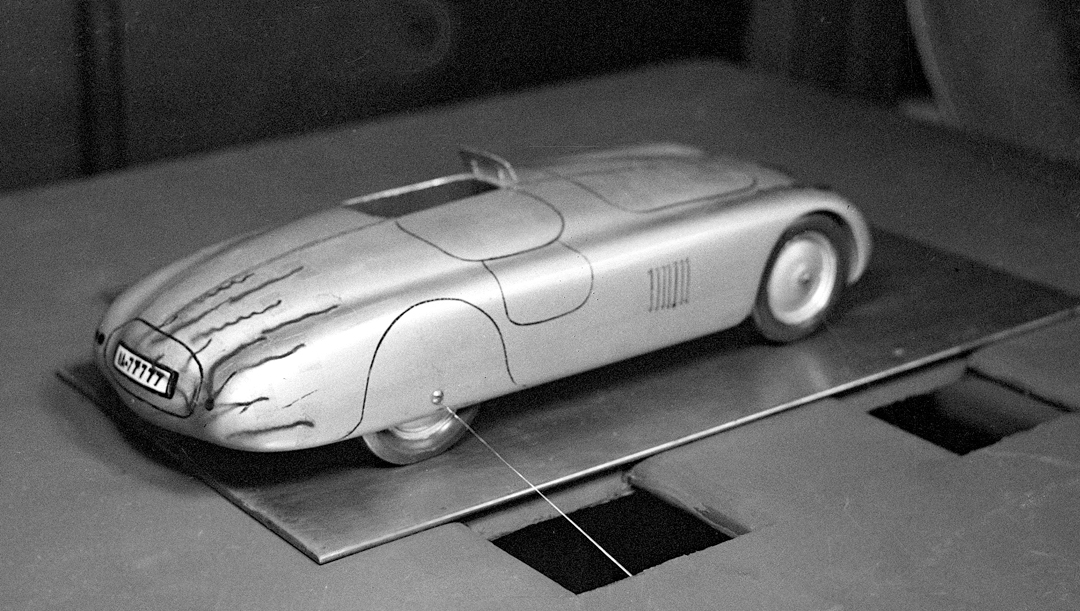

The three-car team made the 24-hour race look easy, with the Schaumberg-Lippe/Wencher coupe finishing 5th overall and 1st in the 2-liter class, and the two roadsters finishing 7th and 9th overall. With such an encouraging result, Hühnlein-directed BMW, under aerodynamicist Wilhelm Meyerhuber, to conduct further wind-tunnel tests, based on the pioneering work of Professor Wunibald Kamm, to more fully develop the new aerodynamic bodywork in both coupe and roadster formats. The result was a new “Kamm coupe” which boasted a .22 drag coefficient and, when tested on the Munich-Salzburg autobahn, achieved a top speed of over 230 km/h, making it the fastest BMW up to that point. With such promising test results it was decided to make a full-scale assault on the April 28, 1940, running of the Mille Miglia, which that year was to be run as a 900-mile, nine-lap race circulating from Bescia to Cremona to Mantua and back to Brescia.

With time, and again BMW’s resources being limited, the NSKK elected to enter a five-car team comprised of the new Kamm Coupe (for Lurani/Cortese), the Le Mans-winning Touring coupe (von Hanstein/Baumer), a new BMW-designed and built aerodynamic roadster (Brudes/Roese) and two more aerodynamic roadsters outsourced for construction by Touring (Briem/Richter, Wencher/Scholtz). The Mille Miglia cars were tuned to run a fuel mixture of alcohol, gasoline and benzol, which raised the power output to as much as 135 bhp, while German tire manufacturer Continental committed to making special high-speed tires for the race, despite international trade embargoes that made rubber very difficult to obtain in Germany. So important was the public relations value of an overall Mille Miglia victory to Hitler, that the overall management of the Mille Miglia team was ultimately wrestled away from the NSKK and handed over to the SS, under the banner of the mounted 1st SS Reitersturm Berlin.

Despite 3-liter, streamlined competition from Alfa Romeo, the von Hanstein/Baumer Touring Coupe drove to a seemingly easy overall victory, beating the 2nd-place Alfa of Farina/Mambelli by over 15 minutes! Finishing in 3rd was the roadster of Brudes/Roese followed by the sister cars of Briem/Richter in 5th and the Wencher/Scholtz roadster in 6th. The Kamm Coupe driven by the Italians Lurani and Cortese was the only retirement, as a result of an oil line failure. Thus, BMW not only claimed the overall win, but the coveted team prize, as well. The triumphant team received a hero’s welcome when they returned to Munich.

Dark Clouds

Just two weeks after the Mille Miglia, Germany invaded France, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands on May 10, 1940. The result was the cessation of racing in Europe and the total commitment of all German manufacturing to the war effort. Or was it?

With Germany and Italy remaining friendly, there was still the possibility of some limited motorsport competition between the two countries. As such, the much-delayed Berlin–Rome race was rescheduled for late in 1940, and there was the suggestion that there might still be some form of a 1941 Mille Miglia. As a result, Hühnlein instructed BMW to conduct some more wind tunnel tests to develop a series of more highly evolved roadster designs. Since open economic channels still existed with Italy, Hühnlein also gave the go-ahead for BMW to commission Touring to construct three of these new “Berlin–Rome” aerodynamic bodies, which when completed weighed less than 400 lbs. These more slab-sided, lightweight bodies were mated to a trio of racing 328 platforms (sourced from circa 1937–1938 racecars) that now produced 120–135 bhp @ 5,500 rpm using a 9.6:1 compression ratio and three downdraft Solex carburetors. The new trio of aerodynamic roadsters were test driven from Milan back to Munich by Mille Miglia-winner Huschke von Hanstein and three other staff members and looked to be very fast and stable. However, as the war spread and more nations became involved, motorsport ceased to be a priority for the Third Reich, and the new cars were set aside.

In the coming years, as the tide began to turn against the axis powers, and bombings of Munich became more widespread, the BMW competition department began hiding the Mille Miglia and Berlin–Rome cars in various remote locations, including farms outside of Salzburg. Interestingly, of the three Berlin–Rome cars built, only one complete car is known to have survived. It was found by American forces after the war and, according to Chief Designer Fielder, was believed to have been used as a daily driver by one of the high-ranking Allied officials during the postwar occupation. Eventually, this surviving 328 MM aerodynamic roadster was acquired by BMW’s Mobile Tradition heritage group and fully restored.

Driving the Survivor

My journey to drive the surviving “Berlin–Rome” car started with a phone call from BMW’s U.S. Director of Heritage Communications, Rob Mitchell. In one of those calls that I receive all too infrequently, he told me that BMW was flying the Berlin–Rome car over for the Amelia Island Concours and that it would be stopping at their Spartanburg, South Carolina, factory and test track facility for two days before flying back to Munich. “Would you like to come out as our guest and have an exclusive test drive?” Jah Wohl!

When I arrived at BMW’s Spartanburg facilities, I have to say I was pretty stunned—they are massive and surprisingly appealing. To one side is the factory, which produces a variety of BMW automobiles including the Z4 Roadster and Coupe, and X5 Sport Activity Vehicle, as well as a small museum housing a revolving collection of BMW history.

Cross the road and BMW has their own sprawling test track facility, which is used for both new car testing, customer deliveries, as well as conducting the many BMW driving experience training programs that the manufacturer offers. Rob informed me that we would have a new separate loop of the track, all to ourselves, once we figured out where they were hiding the car! After a few minutes of wandering the expansive service facilities, Rob was able to open a paint-shop door and there, lurking under the fluorescent lights, was the sole surviving Berlin–Rome car.

Sitting amidst several new but partially disassembled BMWs, the Berlin–Rome car somehow looked otherworldly—almost futuristic. Its slippery, minimalist lines, in conjunction with its metallic silver paintwork, give the car a space-age “Aero” look, which is almost timeless. We spend several minutes just circling the car, before Rob jumps in, turns the key and the 2-liter, 6-cylinder engine immediately burbles to life! If nothing else, the BMW is no prim Madonna to start.

With the help of an escort—to make sure that we’re not accidentally t-boned by a flying M3 as we make our way across the track!—we putter over to our own little test track, which at about 3/4-mile in length has a variety of turns, short straights and a down-hill section reminiscent of Laguna Seca’s Corkscrew!

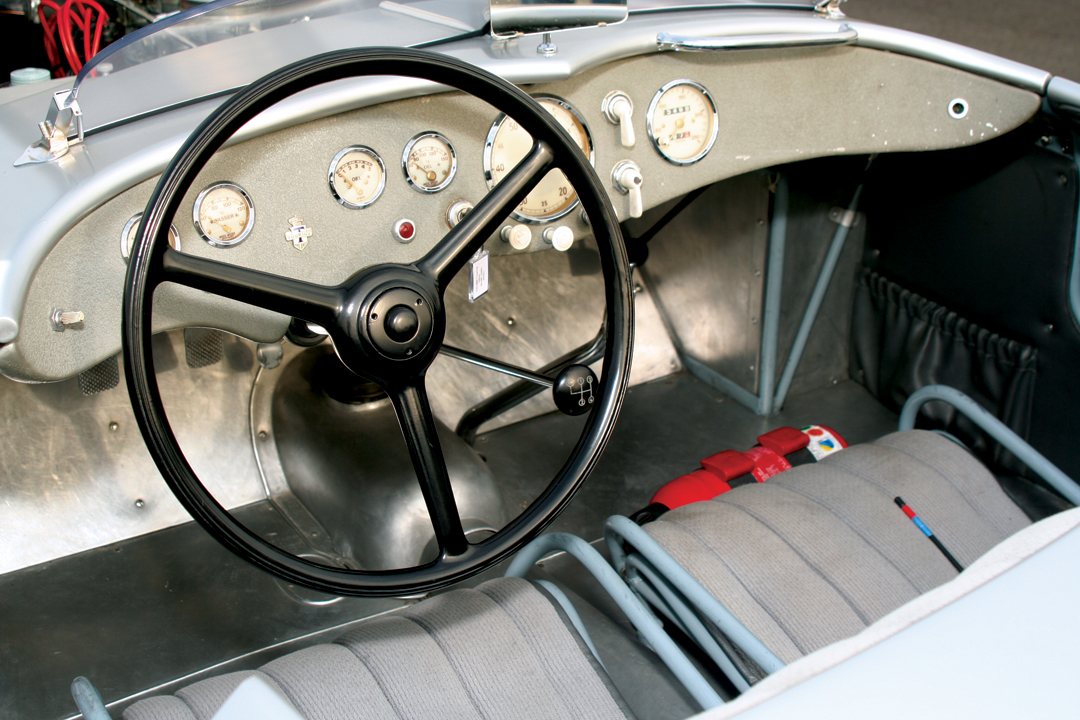

Since a weather system was threatening to move in, our first order of business was getting some photography in. So I coerced Rob to put on the ’30s-era leather cap and goggles that I sourced from Classic Goggles for the occasion and he drove the 328, as I hung out the back of our camera car to take pictures. Despite the often-times low-speed running, and periodic starts and stops, the BMW appeared to be as docile and as composed as any modern-day BMW. With the pictures out of the way, it was now my turn to don the flying cap and goggles and slip behind the big, three-spoke wheel. Climbing through the vestigial door, I plant myself in the seat, which is really nothing more than an upholstered pad suspended within a thin tubular Elektron framework. Overall, the interior is no-nonsense, German minimalism, mixed with a dash of Italian artistry. Looking through the big steering wheel, the driver sees four, small, white-faced gauges for the voltmeter, the water temperature, oil pressure and oil temperature, with a dainty “Superleggera Touring” badge occupying pride of place in the center. Set off to the right of the driver is the tachometer, speedometer and a handful of switches for the choke, lights, etc. Aside from a chrome grab handle for the passenger, the rest of the interior is nothing more than clean, burnished aluminum paneling—very tidy and teutonic, yet possessing an undeniable Italian influence.

Driving position in the 328 is very low, as the driver was intended to be out of the airlflow and below the height of the two small “Brooklands” windscreens on either side. With the gearshift knob close to hand, I dip the delicate-looking, high-mounted clutch pedal and turn the key to the right of the steering wheel—the 2-liter, inline-6 immediately burbles to life. Push the gearshift up and forward for first, let out the clutch and the 328 pulls away without an iota of fuss.

Looking through the Brooklands screen, my field of vision is dominated by an enormous expanse of silver aluminum—looking across the hood of the BMW I’m convinced that you could land a Messerschmidt along it with room to spare. Yet despite the visual cues that say this is a very big car, on the road it feels surprisingly light and nimble—a real testament to Touring’s prewar “super-lightweight” construction techniques.

After a few laps of getting a feel for the car and the Spartanburg track, it was time to see what the 67-year-old was capable of. Downshifting to second out of the final turn before the short straight, I squeeze the accelerator toward the floor, the 328—despite being only a 2-liter with maybe 120 hp—surges forward. Upshift to third, back on the gas, and again the Bimmer lunges ahead. One more quick shift into fourth and the 328 shows no signs of losing steam before I have to get hard on the Alfin drum brakes for a slow, left-right combination that climbs quickly uphill.

Cresting the hill, I downshift back to second and accelerate hard out of the turn and into a series of downhill esses, which reminded me of a mini-Laguna Seca Corkscrew. The 328 drifts out of the first turn with lovely predictability and powers smoothly through the downhill esses, though I now get more of a sense of weight transfer as it quickly transitions back and forth. Once onto another straight that parallels BMW’s high-speed test facility, it is again a series of quick upshifts for a brief glimpse of the car’s top-speed capability. Again, despite its apparent size and relatively small-displacement engine, the aerodynamic roadster—even today using only normal gasoline, rather than the witch’s brew used for the Mille Miglia—seems very capable of top speeds in excess of 130 mph.

As I pound around the rolling South Carolina countryside that the Spartanburg track is a part of, wearing my leather helmet and goggles, I can’t help but daydream of what it might have been like to be upshifting this very same car, somewhere in the countryside between Parma and Piacenza. Who knows what might have been achieved had this Brescian Bridesmaid had her chance at the altar?

Buying and Owning a 328 MM

Alas, this may be a very difficult car to add to your collection. Originally, five aerodynamic cars were built for the 1940 Mille Miglia (including the 1939 Le Mans winner) with an additional three “Berlin–Rome” cars. Of the Berlin–Rome cars, there is the frame of one car (owned by an American) and it’s doubtful BMW would ever part with the one complete example. Likewise, BMW paid several million dollars for the Le Mans/Mille Miglia winner, so that car won’t likely ever see private hands again either.

However, a pair of the 1940 aerodynamic MM roadsters do still exist and are still in private hands, but a precise valuation is difficult as these cars have not changed hands in some time. Of course, the balance of the cars, including the other “Berlin–Rome” roadster and the “Kamm Coupe” never re-emerged after the war. Could they still be lurking somewhere in Germany? Though the cars are known to have returned to Munich after the 1940 Mille Miglia, it is conceivable that some might have made their way back to the racing werks in Eisenach. This could be significant in that after the war, Eisenach became trapped behind the Iron Curtain in East Germany. Could these cars have been cannibalized-for materials or could they still lie buried in some long-forgotten East German farm? For now, all we can do is dream.

Specifications

Bodywork: “Superleggera” aluminum

Wheelbase: 96”

Front Track: 45.3”

Rear Track: 48”

Front Suspension: Floating axle withcross leaf spring

Rear Suspension: Rigid axle with leaf spring

Weight: 780 kg

Engine: 6-cylinder, inline, iron block, alloy head

Displacement: 1,971-cc

Bore x Stroke: 66 x 96 mm

Carburetion: Triple, Solex downdraft

Power Output: 136 bhp @ 6,000 rpm

Gearbox: 4-speed, + reverse

Brakes: Hydraulic Alfin drum, vented back plates

Tires: 5.50 x 16

Resources

The author would like to thank Rob Mitchell and Michael Mitchell for their help in test driving this unique car, as well as Manfred Grunert for historical information and Classic Goggles (www.classicgoggles.com) for supplying the period leather cap and goggles.

Mille Miglia, 1940

Bowler, Michael

Thoroughbred & Classic Cars, May 1975

328, The Trend Setter

Bowler, Michael

Thoroughbred & Classic Cars, August 1975

BMW Since 1916

Grunert, Manfred & Triebel, Florian

BMW Group Mobile Tradition, 2006

ISBN 3-932169-47-6

Mille Miglia, 1927–1951

Clarke, R.M. & Lawrence, M.

Brooklands Books

ISBN 1-85520-4673

Le Mans, 1923–1939

Clarke, R.M. & Clausager, D.

Brooklands Books

ISBN 1-85520-4657