1924 Bugatti Type 13

While many racing cars of the Edwardian period and the early 1920s and 1930s were huge—behemoths to some, especially on dirt-covered roads—there were equally a corresponding number that were miniscule in comparison, many almost fragile in appearance. At first some of these small cars suffered ridicule from bystanders, but only until they started demonstrating the characteristics that were largely lacking in many of the earlier “bigger brothers,” qualities like handling and road-holding. The Bugatti Type 13 was one of these tinier brethren, but one whose reputation soon grew very big.

The Type 13—we will get to the “Brescia” bit in a minute—was in fact the first Bugatti produced in Molsheim, as well as the first to be allocated a Type number by Ettore Bugatti himself. However, the story of Ettore’s cars is far more complicated and started a good bit earlier than Christmas of 1909 when he set up his own company at Molsheim. Thanks particularly to the work of H.G. Conway, the Bugatti chronicle is now fairly clear, though it would be fair to say that most enthusiasts who are interested in Bugatti tend to date their interest with the Type 35 Grand Prix car that first appeared in the company catalog in 1924, with the first few models running in public in 1925.

Latter day enthusiasts may well believe the Veyron is the only Bugatti, but the early history is fascinating and gave rise to several models that were superbly quick and successful, and demonstrated Bugatti’s engineering and design brilliance from a very early point in his career.

Ettore Bugatti…the beginning

There are three eras that can be clearly defined in Bugatti’s working life. The first was the period during which he acted as a consulting designer for a variety of firms. This was from the years 1898 to 1909. At the age of 16 he was working for the Milan tricycle manufacturers Prinetti and Stucchi, and he bought one of their tricycles, modified and raced it in 1899 in several events. This tricycle had two engines, and he also built a four-engined car the same year. He designed and built a more conventional car in 1900-’01 for Count Gulinelli, which most historians now retrospectively call a “Type 1.” He was doing design work for de Dietrich in 1902, and produced a large “production” car that competed successfully in several races. Then came a 50-horsepower car for the 1903 Paris-Madrid race, and he created two more models before leaving de Dietrich in 1904, designing the Hermes Mathis for Emil Mathis at Strasbourg.

By 1906, Bugatti had established a reputation as an independent consulting engineer, and designed two cars for the Deutz company in Cologne, including a four-cylinder overhead camshaft machine with a four-speed, chain-driven gearbox and a Bugatti-design clutch, characteristics that would appear later on his own Type 13 and Brescia. He did work for Isotta Fraschini, and later more designs went to de Dietrich. At a very early age, Ettore Bugatti was highly respected, in spite of the fact that he had never had any formal training as an engineer. In fact, the family expectation had been that he would go into the arts, a role taken over by his younger brother Rembrandt, who became a noted sculptor.

The Type 13

While at Deutz, and partly inspired by the Isotta Fraschini, Bugatti seemed to have developed his interest in smaller cars that were very light in weight. This is at least partly related to his leaning toward voiturette racing, which was beginning to expand, although it would be a few years before it became a recognized category. While employed as the works manager at Deutz, Bugatti designed and built a very small, four-cylinder, eight-valve-engined car with half-elliptical springs at the rear. He built this car in the cellar of his own house in Cologne. This was the prototype Type 13 though, confusingly for non-experts, it was allocated the designation Type 10 by Conway and Pozzoli. These early type designations were used as a mechanism to identify all the Bugatti cars pre-Molsheim. The Bugatti family owned this car up until WWII, and it still exists today.

Bugatti, tired of working for others, was taken to see an existing dyeing factory premises in Molsheim, which he took over to start production of his own cars. This began as early as January of 1910, and the first series of production Type 13s were very similar to the 1907-’08 prototype, with semi-elliptical rear springs, and a 65 mm x 100 mm four-cylinder engine. It was this car that was considered to be the first pur-sang Bugatti…pure blooded. The design of this car represents a style that Bugatti stuck to for most of his career…an aluminum crankcase bolted to the frame and a cam box with overhead valves. The early cars had a squarer radiator than the oval design that would soon become universally recognized. With the Type 13, he was the first manufacturer to pay serious attention to building a lightweight car, with all the components designed to integrate with the overall design. Thus did the Type 13 become an exhilarating car to drive. Five cars were built in the first year of production.

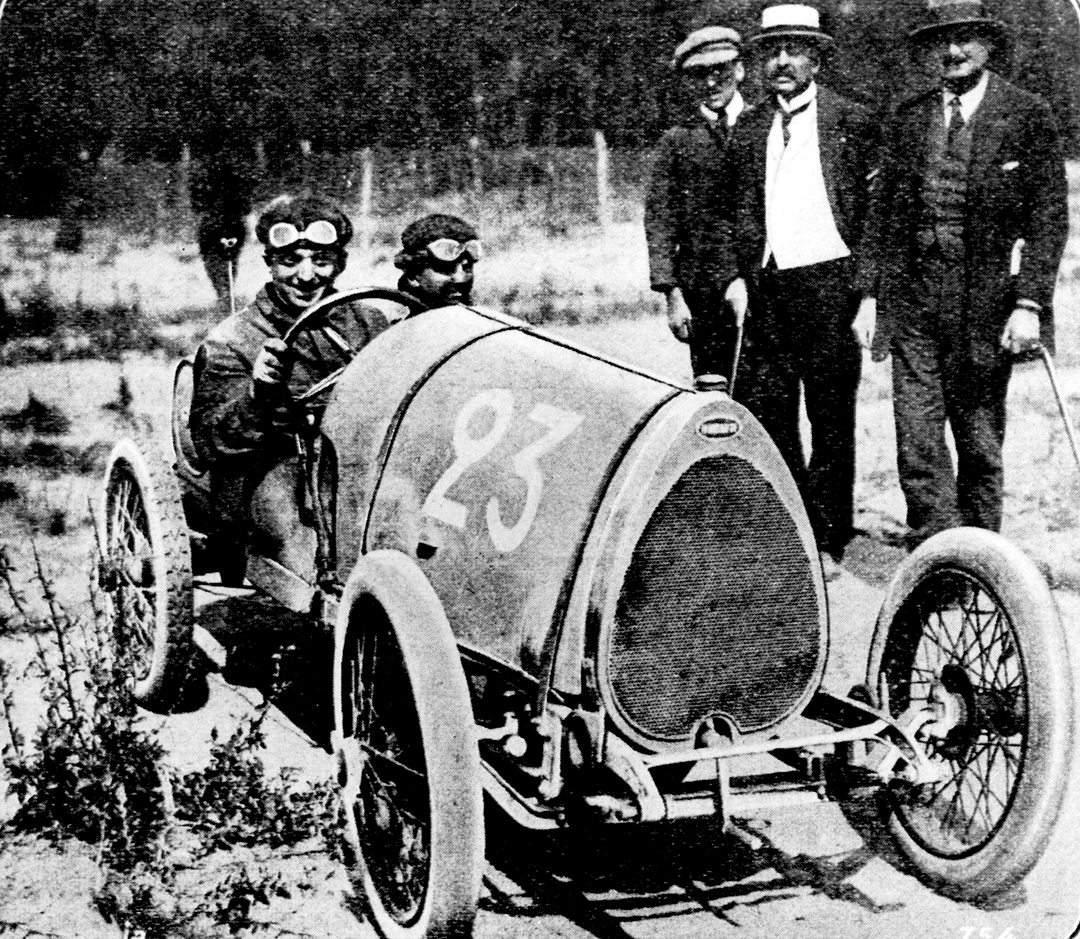

The first Type 13s had a capacity of 1327-cc, with a two-meter wheelbase and track of 1.15 meters, with the single semi-elliptical rear spring. Hugh Conway points out that technically, the pre-1914 8-valve, 4-cylinder cars should be referred to as Types 13, 15, 17, 22 or 23, all depending on which length wheelbase was used, as well as some other chassis details. However, as so few of these cars survive, they have all been historically referred to as Type 13. The first production cars were successful as soon as they appeared, gaining attention for wins and good placings in hillclimbs in the small touring class. Early press descriptions called the 770-pound machine a “dainty looking vehicle…more of a toy than a real car.”

The English magazine The Motor described the new car at the end of the first season: “It is driven by a little four-cylinder monobloc motor, rated by its owner as 5 ½ hp. The motor is a remarkably fine piece of work and abounds in interesting features. The single block of cylinders is mounted on an aluminium crank-case attached direct to the frame members. The crankshaft is carried in two large ball bearings, and the pistons are of steel. The valves are mounted in the cylinder head, with vertical stems, and are operated by a single overhead camshaft, obtaining its motion from the mainshaft by means of a vertical spindle and bevel gearing. All the valve mechanism is enclosed in a bronze housing bolted to the head of the cylinders and carrying the camshaft bearings and the bevel gear of the vertical spindle. On the left-hand side is the exhaust, there being a separate port for each cylinder, the four arms being united to a single exhaust pipe.”

In this report, W.F. Bradley goes on to describe how the engine, designed to run at 2300 rpm, could be pushed to 3000 rpm without danger due to the use of the finest and most expensive metals. Thus, he says, this little car, which looked like it should have sold for £120 was on the market for £300, making it the most expensive car of its type at the time. It is interesting to note that a number of early reports had numerous technical errors…most Type 13s had plain bearings to carry the crankshaft.

Bugatti experimented with different wheelbases and twin semi-elliptical rear springs. The exact specification of these modified cars determined whether they were 15s or 17s until 1914 when they were known as 22s and 23s. The early 8-valve cars had many successes in competition. At the race at La Sarthe in June 1911, Bugatti Type 13s were driven by Gilbert, father of two later racing driver brothers, and de Vizcaya, the banker who’d helped establish Bugatti at Molsheim. These two cars had numerous wins at major hillclimb events, and brought significant praise and attention to Molsheim. Between 1910 and 1920, the 13 and its other 8-valve variations numbered some 435 cars. Bugatti worked on other projects as well during this early period, including the well-known Type 18 5-liter car. This racing machine was made for Bugatti’s friend, the sportsman aviator Roland Garros, and was dubbed Black Bess. In 1911 Bugatti produced a design that he sold to Peugeot, and the design may have actually preceded the Type 13. It was known to some as the Type 12 and also the Type 19. Nevertheless, this car had a 55 mm x 90 mm side-valve engine with 855-cc, a cone clutch and a two-speed gearbox that eventually became three-speed. This was the Bebe Peugeot or Baby Peugeot, of which some 3,095 were made between 1913 and 1919. My friend in Italy, Gianni Codiferro, has one, and we have competed with it at the Silver Flag Hillclimb. It is the essence of a very small and very early production machine that could be used in competition. The thrill of getting it to the top of the nine-kilometer Italian hill was only matched by the terror of running it back down with only nominal brakes! Many enthusiasts view Bebe Peugeot as the “Mother of Bugatti!”

The Brescia 16-valve

In the years 1913-’14, Bugatti was aware that the Coupe International des Voiturettes class was to be revived and expanded in 1914. Thus he set to work designing an improvement of the Type 13 to be used in voiturette racing. This comprised a 16-valve engine with 66 mm x 110 mm bore and stroke using the two-meter Type 13 chassis length. Three cars were built for the first race, but the Great War put an end to that and the 1914 event never happened. The cars went into storage…whole and in parts!

War was looming imminently in mid-July 1914. Bugatti took some racing cars to Italy, and three Type 13s remained at Molsheim, where many parts including camshafts were buried in the grounds. Bugatti was in Milan and then moved to Paris where he and his family lived throughout the war years. Ettore Bugatti designed and supervised the building of aero engines. One effort included the building of an aircraft engine that was sold under license to the French, Italian and American governments. A factory was built in Elizabeth, New Jersey, to build these engines under the management of the Duesenberg brothers.

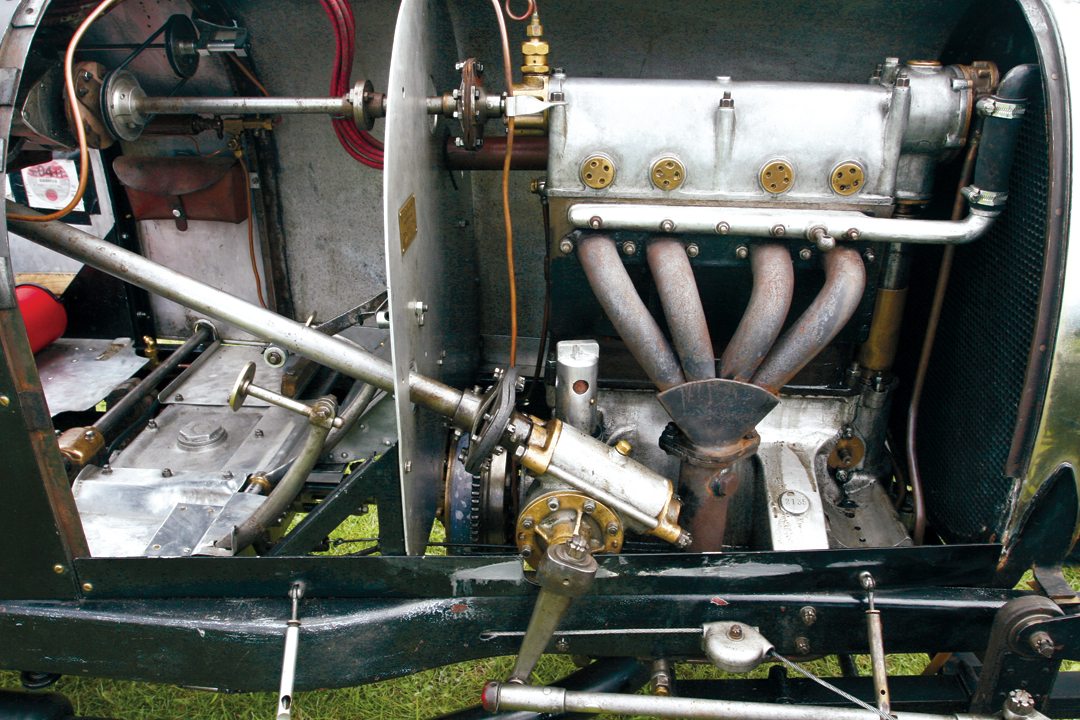

In 1920, racing returned to Le Mans where the cars, which had been in storage for six years, were entered and Bugatti’s long-time associate Ernest Friderich won the race. This post-war success was followed by entry into the voiturette race at the Italian Grand Prix at Brescia in 1921. Bugatti had continued to modify the 16-valve car after Le Mans and ran it with ball bearings for the crankshaft. The cars that swept the first four places at Brescia had an increased bore of 68 mm, giving a larger capacity of 1453-cc, used roller-bearing big ends, a 3 to 1 top gear ratio and tires that measured 710 x 90. It weighed in at just over a thousand pounds and developed maximum power at 3350 rpm. The eight spark plugs were used with twin Bosch magnetos mounted in the dash. This provided, and still provides, an interesting effect in the rain as the driver is treated to a lively display of flying sparks! The mags were driven from the rear of the overhead camshaft.

Friderich won the 200-mile race at an average of 72 mph and thus established the record for the fastest ever “light car” race in the world. De Vizcaya was 2nd from regular drivers Baccoli and Marco. The great Minoia, who would later race Bugattis, was next in an O.M., 14 minutes behind the leader on the 10½-mile circuit. As a result of this stunning and widely celebrated victory, the cars became known as the Brescias. There was a further version known as the “Brescia Modifie,” which had a similar engine with only a single magneto, and used the slightly longer 22 or 23 style chassis. Most of the Brescias had a wheelbase of 2.4 meters, the Modifie had 2.55, but all had a track of 1.15 meters.

The chassis frame was of channel section, which did not vary in length except where they tapered off at the ends. There was some bracing where the scuttle joined the top of the channel section, and the engine was used to brace the forward section, with the gearbox a separate unit anchoring the center section. The frame was very light, but had considerable strength due to this stiffening process. There were three crossmembers, two in front of the rear axle and one behind. Bugatti had designed a clever system whereby the Le Mans cars had split-ended tube fitting into the channel of the frame, whereas the Brescia cars used straight tube connected to the front shock absorbers, allowing variety in setup. The earlier Brescias had the pear-shaped radiator, which became more oval-shaped after 1923. Bugatti, it is thought, didn’t have a pear in mind as his model, but rather horse shoes, using the classic arch design. Early brakes had cast iron shoes, which were later replaced by Ferodo linings. The gearbox was compact and was—and is—easy to use, with well-spaced ratios. There were numerous ratios available for the various versions, and the location of the gearchange moved about. The steering wheel was a pure Bugatti design, most having four flat spokes, very light but also very strong.

The racing Brescias

The Brescias amassed a large number of victories and impressive performances in competitions after the 1914-18 war, including races, hillclimbs and sprints, and they did very well at places such as Brooklands. There was the victory at Le Mans in a race that was four and a half hours long with a winning average speed of more than 57 mph, and then the 1921 Brescia triumph. In October of 1921 there was an important race at Brooklands where de Viscaya brought his Brescia home 4th behind the all-conquering Talbot-Darracqs. In 1922, three cars built for Crossley Motors finished 3rd, 4th and 6th in the Tourist Trophy race on the Isle of Man.

Raymond Mays was perhaps the most successful British driver with a Brescia. He had brought a car he called Cordon Rouge to the UK in 1922. It had plain bearings and managed 4500 rpm. Mays and Amherst Villiers modified this engine themselves to see 6700 rpm, and then with a second car, Cordon Bleu, a ball-bearing car, they achieved 6900 rpm. Careful attention to cam design and restricting these cars to hillclimbs and sprints meant they were reliable in these events and very fast. Cordon Bleu was placed into the hands of a novice driver by the name of Francis Giveen by Raymond Mays. He drove it at the challenging little hillclimb known as Kop Hill in Buckinghamshire in England in March 1925. Giveen was an Oxford undergraduate, and for some reason Mays thought he could drive the car. Giveen managed to invert it in a practice run near Mays’s home at Bourne. Mays was going to drive at Kop Hill, but was prevented from doing so by S.F. Edge who said his AC contract prevented it.

Mays stood beside Giveen at the start of the 1000-yard run to assist him in his first run. The car would only run on full advance at high revs and one almost needed three hands to get the car in gear, release the handbrake and open the advance and retard lever. Off went Giveen, and after the two right-hand bends “jumped a pit dug out in the bank, knocked over a group of Vauxhall mechanics who had come to watch the racing, and bounced back on the road to cross the finishing line.” Amazingly, no one had been killed, but the meeting was immediately ended and all speed events on public roads came to an end.

Driving a Brescia…at Kop Hill!

Last September marked the centenary of the first event at Kop Hill, with no further racing happening there until it was revived as a demonstration in 2009. I was invited by Peter Livesey, who edits Brescia Bits and has done so for some years, to drive his lovely patinated Brescia. There were five Type 13s in the entry list, including Cordon Bleu, which caused the Kop Hill to be closed originally, along with all other competition on British roads, some 85 years earlier. Actually, though Karl Foulkes-Halbard’s Brescia is called Cordon Bleu and has that car’s original registration, all the experts say that neither Cordon Rouge nor Bleu survive.

So, in front of a huge crowd, with hundreds of very old cars and motorcycles, the 2010 event got under way. I was delighted to reacquaint myself with a Bugatti, having only ever driven a Type 51 some years ago. These little Brescias are fascinating—and very fast.

Peter Livesey’s car, chassis BC 042, is a 1924 car in well-used condition—he has competed with it regularly for sometime—you would not call this car “over-restored,” as the patina is wonderful. It had arrived on this bright sunny day from home an hour or so away on its skinny Avon tires, 4-00/19 front and rear. All the Brescias were driven to the event, no trailers in sight. The dash features an 8-inch handle for the fuel pump on the left, a rev counter reading to 6500 mounted upside down for easier reading, and the two magnetos in the center behind the four-spoke steering wheel. These cars have a central throttle, and the gearshift and handbrake are mounted outside the body on the right. The gearbox was quite simple to learn, and the clutch well-behaved, needing not a lot of revs to get it going; about 2500 rpm will do it. There is an oil pressure gauge on the right with the rev counter and fuel gauge over on the left. The car, sitting on its own in the sunlight, is stunning. It has the later radiator shape, wonderful old wire wheels on dark blue painted rims, and a fascinating fuel tank with its own external gauge mounted behind the driver just behind the rear axle.

Before my run, Peter advised that it was set a bit lean, so one would have to make sure the revs didn’t build too quickly. I was glad for the advice as the needle really did shoot up, necessitating a quick gear change to second off the line. The car has a wet clutch, so you need some revs before you can “snick” it into first gear. This is a 4-speed box, with first left and down, second straight up, then third and fourth. For reverse, press the button and go over the gate! Oil pressure was critical so I kept a close eye on the gauge, but in fact it never wavered nor misbehaved on this coolish day. The fuel pump gets a few pumps before the start and as it maintained 50 pounds pressure all the time, didn’t need any attention during the runs. The ignition had a bit of advance, so with the magnetos switched on it was set to go. The last advice from Peter was to remember that the brakes, though on all four wheels, were biased to the front so the handbrake comes into use for any serious braking.

While sitting on the start line, I could reflect a bit on the history of this car. Originally, it was exported, probably new, to Australia. Peter has had it since the 1980s, and it came to him as “boxes of bits.” It is thought to be the ex-Maria Jenkins car that raced at Maroubra in Australia, and the very old bonnet shows evidence that it is from that car. This car has a Type 30 chassis with a racing history, and the Type 30 was a development of the Brescia, an extended chassis with outboard spring hangers. The chassis number and an engine number are the identifiers, and they are stamped on the crankcase. The “Brescia” number for this car is 2135. The car was bought from an Australian opal hunter and a number of years went into putting it back together. It has been running regularly for the last five years, and has done many historic tours.

Driving the car was as wonderful as expected. In spite of the very high center of gravity, which makes it very challenging for circuit racing, I was surprised how “at home” I could feel with all that exposure on the semi-open sides. That comes, I guess, from putting most attention on not over-revving and not forgetting that the “throttle is in the middle”—that’s important. When the flag came down, a superb sound blasted from the exhaust and the little car really did rocket off the line. I was up to second very quickly, using about 4500 to 5000 rpm, then going to third. The effort went into discovering how much grip would come from those narrow tires. In fact, it was grippy, but the main sensation leaps from its nimbleness. It tears up this very thin bit of road, which is bumpy and off-camber. The Brescia dances over the bumps, the front and the rear both move about under acceleration and it dips into the first, then second and then third corners, and keeping the revs up is not put off by the change in altitude. I think we were hitting just over 60 mph near the top, remembering this was a “demo,” not a race. It was a bit quicker at the end of the second run. The braking was challenging—you really do have to use the handbrake if you want to stop in a hurry—but that is all part of the nature of the pur-sang racing car, this 86-year-old pure-blooded racing car. Loved it. Loved it.

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis/Body: Bugatti Type 13 Brescia

Engine: 4 cylinders 16 valves

Bore and stroke: 66, 68 and 69 x 100 mm

Capacity: 1453-cc

Power: 30 BHP @ 4000 rpm

Valves per cylinder: Four

Camshaft drive: Front, bevel

Crankshaft bearings (no. and type): Early, 3 plain; later 2 ball bearing, 1 plain, plain rods

Carburetion: 1 or 2 Zeniths

Clutch: Wet multi-plate

Gearbox: 4-speed + reverse, separate, central

Wheelbase: 94.5 inches

Track: 45.3 inches

Suspension: Semi-elliptical rear spring/s

Resources

Many thanks to Peter Livesey for his generosity and Bugatti expertise, and to Kop Hill organizers for their assistance.

Conway, H.G. Bugatti – Le Pur-sang des Automobiles Haynes Publishing UK 1973 Edition

Conway, H.G. Bugatti – Video, Reference and Data Book Wychwood UK 1989

Eaton, G. The Brescia Bugatti Profile Publications UK 1967