In 1966, the rain in Spain didn’t stay mainly on the plain. It blew eastward to the Ardennes Mountains of Belgium, and hurled itself down onto the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa Francorchamps, one of the regions unfortunately prone to such downpours. One lap into the race, Jackie Stewart and the BRM you see here flew off the road, bringing the Scot to the very edge of a critical accident. It started the Jackie Stewart safety campaign that changed motor racing circuits, cars and drivers, and which continues to this day. Rather like Stewart, who escaped relatively unscathed, the car had used up one of its lives…not its first, and certainly not its last.

BRM in the 1960s

VR regulars will recall that we have done BRMs before…the P25 that was the first from the Lincolnshire firm to win a World Championship race, a V12 P126 that had been driven by Rodriguez, Attwood and McLaren, and an H16, which was another Stewart machine. The P261 also has an Attwood, as well as the Stewart, connection. For those of us who have been around for a while, BRM was symbolic of great hope against the odds, the underdog against a stronger and richer opponent, touches of brilliance, and years of incompetence. BRM attempted to raise the British flag in post-war industrial Europe, but struggled in taking over a dozen years to do it. And, when it nearly got to the top, it was close to giving up. BRM is a great story.

I was going to mix my metaphors a bit in telling this tale by introducing the notion of “six levels of separation”…the idea being that if you sat in this car or met one of its drivers, you were then only a step away from a connection with most of the great drivers of the world. However, when I discovered that there have been endless battles over the true identity of the person who thought up the term “six levels of separation”…Milgram or Karinthy or others…I decided to pass on the metaphors and just tell the story!

Although BRM had been founded in 1945, the first V16 didn’t appear on circuits until 1950, and the initial BRM Trust set up by Raymond Mays was taken over by Alfred Owen in 1952. It won a few short, minor races, but it wasn’t until 1959 when the P25 won the Dutch Grand Prix that the company was really taken seriously. The Constructors Championship was established in 1958 and BRM was 4th behind Vanwall, Ferrari and Cooper-Climax. It was 3rd, 4th and 5th in the following three years, and in early 1962 Alfred Owen said that the team would close down if it didn’t win the title that year. Graham Hill ensured that it did win when a 10-cent part in Jim Clark’s Lotus failed in the final race. Hill and Richie Ginther tied for 2nd spot in 1963 in the BRM P57 and P61, but were well beaten by Clark that time. The P261 was introduced in 1964 and the title went to the wire, Surtees in a Ferrari just beating Graham by a point.

The P261

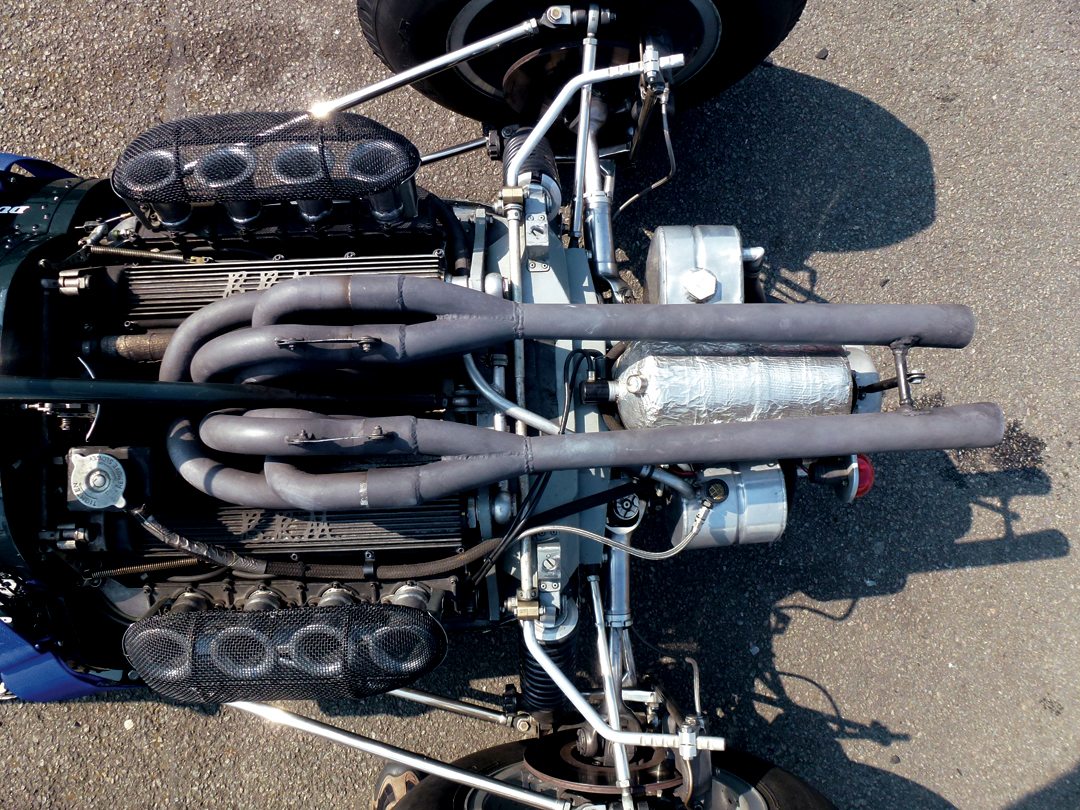

The P261, sometimes known as the P61 Mk II, hence P261, incorporated all the lessons learned with the part monocoque/part space frame P61, and became the first true BRM monocoque. By the time it had been developed for the 1964 season, it was the neatest and structurally purest stressed-skin monocoque GP car from any of the manufacturers. It featured what Tony Rudd called “fully adjustable suspension,” and was constructed with a rolled and welded outer skin with a pre-fab inner inserted and the two riveted together to create the “stressed” fuselage. The car ran on 15-inch wheels as opposed to the 13-inch rims on

P61, as Dunlop had created a new tire for 1964. The new car was tested twice at Silverstone and made its race debut at Snetterton on March 14. Though the new car, 2612, was quick in practice and the early laps of the race, Hill crashed and it was “written off.” It actually survived, but didn’t race again.

Hill and Ginther then raced 2613 and 2614 for the next five races, and Hill took his second consecutive win at Monaco. Hill raced a brand-new and improved car at Spa, chassis 2615, on which much work had been done to enable speedier adjustment of roll centers and other suspension changes. Hill was 5th at Spa. At Monza, 2616 appeared. Until now, the BRM V8 had exhausts on the outside of the engine, but on 2616 they were in the center of the vee. The car’s clutch failed at the start, but Hill won at Watkins Glen in this chassis.

Ginther then left the team, so Hill was joined by a relatively little known Scot by the name of Jackie Stewart for 1965. Stewart had the brand-new chassis 2617, our feature car, and both Stewart and Hill had the center exhaust setup. Hill was in 2616 from the previous year, and this would be his regular mount for 1965. New boys Stewart and Jochen Rindt celebrated the night before the South African race—New Year’s Eve—by going to a drive-in movie! Hill finished 3rd and Stewart was 6th even though the water and the fuel ran out.

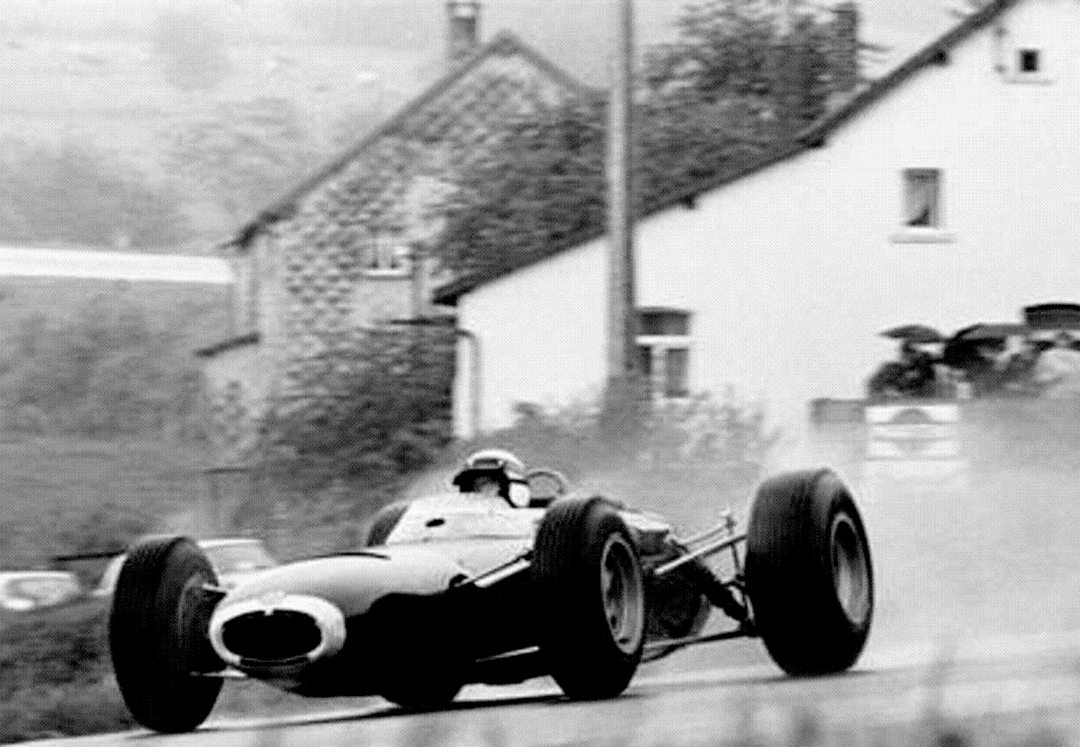

Stewart was then 7th and 4th in the two-heat Race of Champions at Brands Hatch in 2617, and at Goodwood for the Sunday Mirror F1 race, he qualified 2617 on pole, and was running 2nd when a camshaft broke. He made up for this by winning the International Trophy event at Silverstone, his first F1 victory. Hill won again at Monaco and Stewart took 2617 to 3rd place, followed by a very impressive 2nd at Spa behind Clark. Stewart had now really arrived in Grand Prix racing and the vehicle that got him there was 2617. Spa, however, would come back to haunt the car and the driver.

Photo: D. Hodges

Two weeks later, Stewart repeated his 2nd place at the GP de l’ACF at the twisty Rouen circuit, again outqualifying his illustrious teammate. Hill reversed this on home ground at Silverstone, finishing 2nd to Stewart’s 5th, as 2617 suffered from oversteer all through the race. Graham’s pole position at Zandvoort turned to 4th in the results, while Stewart moved from 6th on the grid to 2nd behind the winning Jim Clark. At the Nürburgring, Stewart retired with suspension damage, not surprising if you have seen all those famous photos of #10 flying two feet off the ground in that race. Monza provided a thrilling race, with Stewart leading 40 laps in 2617 and Hill ahead on 17, but it was Stewart in front by a nose at the end. Again, Hill came back to win at Watkins Glen while “wee Jackie” retired with a bent rear wishbone. At the final round in Mexico, Stewart blew 2617’s engine in practice so moved to 2615, while Hill stayed in 2616, but both retired. Thus Clark won the championship from Hill and Stewart, and Lotus took the constructors crown from BRM by nine points. It had been a good season.

1966…and beyond

BRM was one of the British teams “caught out” by the introduction of the 1.5-liter formula for 1961, but indeed was the team that caught up with Ferrari in 1962 to steal the title. The formula lasted through 1965, but yet again teams were not prepared for the 3-liter regulations that began in 1966.

For the South African race, a non-championship round, Lotus had the enlarged 2-liter Climax unit, Hulme’s Brabham had the 2.7 Climax, while Jack himself had the new 3-liter Repco. There were no works BRMs, though a number of privateers had older 1.5-liter engines to use. BRM had gone “down under” for the Tasman series, and a chance to try out some ideas for the 1966 F1 season. BRM had not gone to New Zealand and Australia in 1965, mainly for reasons of cost. Tony Rudd didn’t plan to go in ’66 either, until Alfred Owen said the Rubery Owen Company needed business links there. Graham Hill didn’t want to go, thinking the stretched BRM 1916-cc unit wouldn’t be competitive. It was decided he would do some races, and be in the UK part of the time to test the new 3-liter BRM H16 engine which was behind schedule.

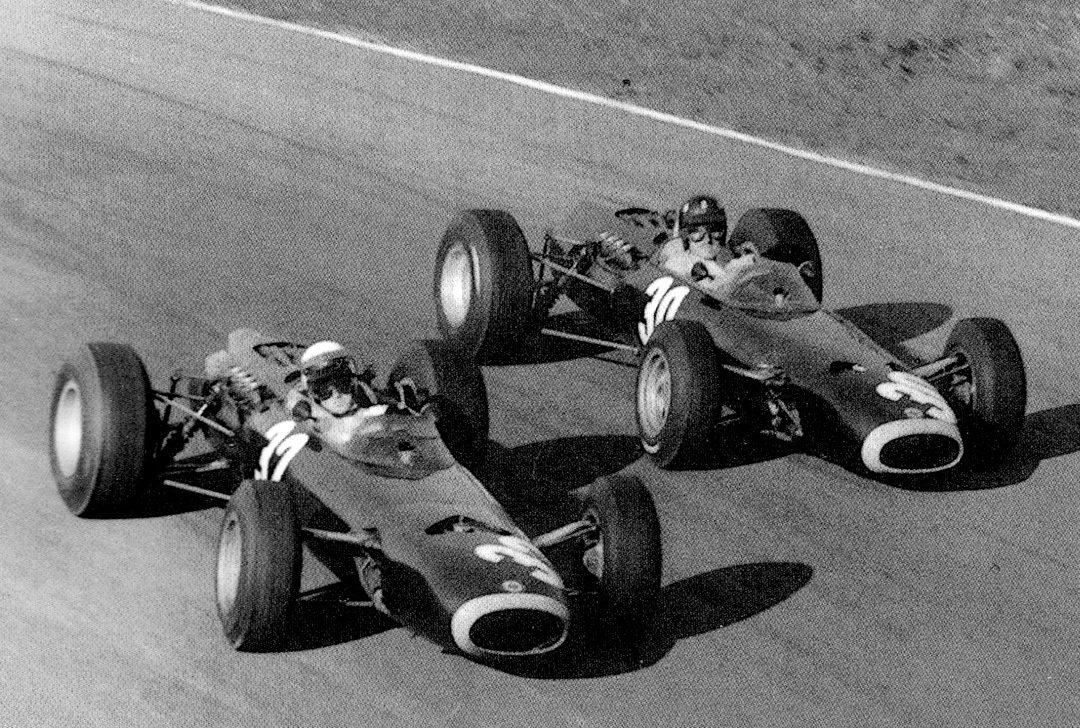

Photo: Ferret Fotographics

The first race was the New Zealand Grand Prix at Pukekohe, where Hill won with the center exhaust 2616, now with a 1930-cc engine. Stewart was to drive 2617, but it was stuck on the ship so he had 2614 with side exhausts and took a good 2nd. A week later at the Levin Grand Prix, Stewart was in his usual 2617, while Attwood took over 2614 as Hill returned home and would not agree to anyone else driving 2616. Stewart took 2nd and Attwood 4th in the prelim heat. In the main event, Stewart had gearbox failure after a spin and Attwood took a very good victory in his first race for BRM since 1964. He had done much BRM testing, and was a very able race and test driver.

One week later, the BRM pair was at Christchurch for the Lady Wigram Trophy on the South Island of New Zealand. Neither driver had been there before, but both were on near record practice times. Attwood was getting the side-exhaust 2614 running well when Stewart decided he wanted that car. Attwood was relegated to 2617, but won his heat, while Stewart won the second heat. In the final, Stewart and Clark led Attwood and Frank Gardner. Frank’s brakes failed and he hit Clark, so the two BRMs came home 1–2, Stewart taking the win. Back home, the prototype H16 engine was being run for the first time. At Teretonga, Stewart and Attwood, still in 2617, were 2nd and 5th in the heat, but in the main race, local drivers Spencer Martin and Ian Dawson got into the lead group. Cars touched in the “loop” section and Attwood and 2617 flew off the road and flipped over, with Attwood trapped in the car. Martin and Dawson got him out. Attwood was a bit banged about, but still headed off to the USA for another event as Graham Hill was returning to the Tasman series.

Initially, repairs were made to the forward skins on 2617 at a local garage, but it was decided to return the car to England for a rebuild after a stopover at a show in the Far East, having used up one of its lives. Stewart won three of the remaining races, winning the title, and everyone had been very pleased with Tim Parnell as the team manager for the Tasman races—it had been a great success for BRM. Back home, twenty 1.5-liter engines had been converted to 2-liter Tasman specs, and some had gone to Matra for the new Matra sports car. The plan had been that two H16s and two 2-liter cars would go to Monaco for the opening Championship race. In the end, 2616 and 2617 went for Hill and Stewart with 2-liter engines, while 2615 had gone to Bernard White’s team for Bob Bondurant. Chassis 2617 had engine number 6009…the same engine that is in it today. The prototype H16, 8301, also went and Hill did eight slow laps. Jim Clark put the Lotus 33 Climax on pole from Surtees in the V12 Ferrari, Stewart in 2617, Hill and Bandini in the second Ferrari.

The plan was for Stewart to harass Surtees into breaking down, and for Hill to do the same to Clark. Stewart did wear Surtees down, but Clark was in early trouble with his gearbox and Graham was having an intermittent problem with his car. Stewart moved into a good lead even though he had lost 5th gear. A battle raged between Bandini, Hill and Clark until Clark retired. Hill hit a kerb but continued, and Bandini drove as fast as possible but couldn’t catch the flying Scot. It was a superb win for 2617. Stewart had experienced considerable understeer in practice and bent a few wheels, but the handling had seemed much better in the race.

For Spa, Stewart and Hill had their regular 2-liter cars as well as two H16s to try. They decided to race 2616 and 2617 as usual, with Stewart 3rd quickest and Hill 9th. Stewart made a bad start and was only 6th chasing Bandini. The loudspeaker report said he had overtaken Bandini, and then there was silence. After some time, a few cars trickled in. It was obviously raining near Stavelot. Hill had gone off on oil and noticed Stewart trapped in his very damaged 2617 in a ditch. He and Bondurant went to Stewart’s aid and got the fuel-soaked Scot out of the crushed monocoque. Stewart recalled that he had aquaplaned in the Masta Kink and hit a fence post and then a pole. He was trapped in the car by the steering wheel, having suffered a shoulder fracture. Stewart was very lucky and only missed one race before returning to the fray. The 1966 World Championship went to Jack Brabham, with Hill 4th and Stewart 7th. BRM ranked 4th among the constructors. Stewart had been significantly traumatized by the Spa crash, and it did not come as much of a surprise when he became a very safety-conscious driver. He was the first driver who actively campaigned on a number of issues, particularly circuit safety.

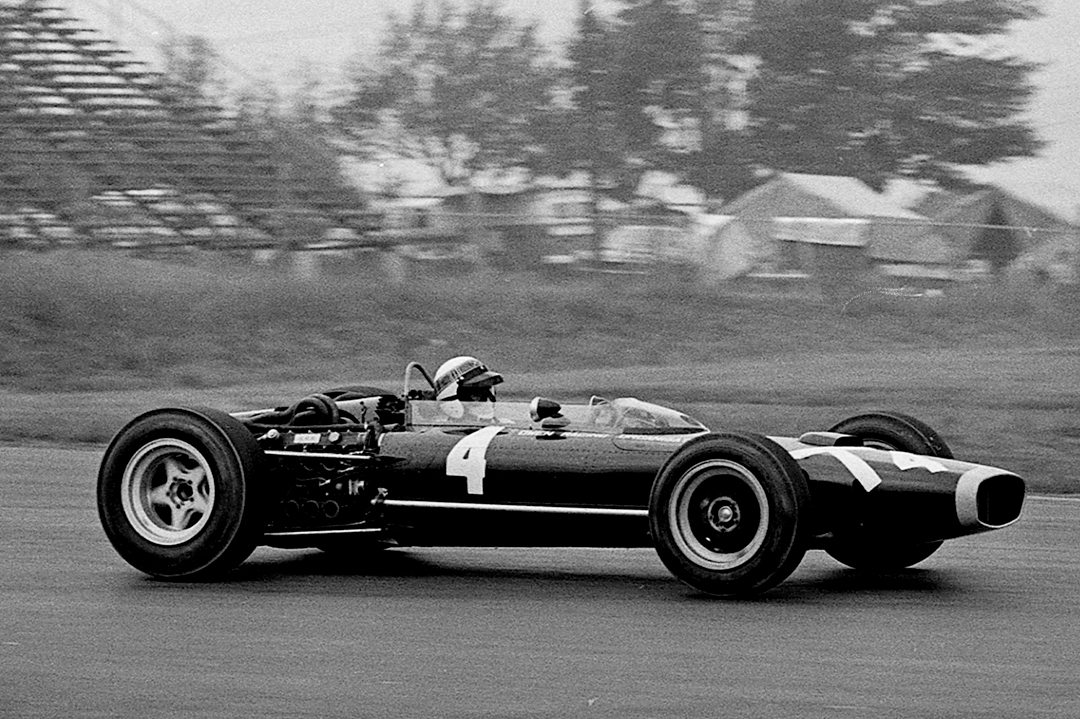

Photo: R. Forster

2617—come to life again

Not surprisingly these days, there is some controversy about 2617. BRM mechanic Alan Challis said that, “we dragged Jackie’s car out on its wheels, took it back to Bourne and binned it. I think we actually sent the wreck up to Darleston and it was scrapped there. I doubt any of it survived.” However, there are counter claims that it was dismantled, though clearly the original monocoque was finished…that is evident from photos. Nevertheless, team reports indicate that the car was available because the oil tank from 2617 was tried on 2616. While the usually accurate reports in the Sheldon and Rabagliati volumes have 2617 doing several more races than it did, the Nye research is somewhat more detailed, though it is also based on first- and second-hand accounts.

Chassis 2617 had been the sixth and final P261 BRM to be built, and it was intended to be Stewart’s car for the 1965 season. It had the stressed engine mounting and did not have the “letter-box” tunnels through the rear chassis section to allow use of the side exhaust system. Some changes were made to the car when it was repaired after Attwood’s Teretonga accident, and it then carried on in 1966 as Stewart’s regular car. Nye attests that the car was taken back to Bourne after the Spa crash and “stripped of all usable salvage.” Though the chassis was finished, a fair amount must have remained, including the engine and the gearbox. BRM driver Richard Attwood had always liked the P261 and in the later 1970s said to Rick Hall, then of Hall & Fowler, now Hall & Hall, that if ever the parts became available, he would like a P261 built up.

Hence Kerry Adams built a monocoque replacement chassis for 2617 using the original drawings and this was fitted with one of the 2-liter Tasman V8 engines “and numerous period components.” The project had some finance from Mike Ostroumoff, and he and Attwood now own the car. It went on to do many historic events over the years, and when Attwood won the Glover Trophy at the Goodwood revival he was thrilled, as he had made his F1 debut at Goodwood in 1964 in a BRM P57. The car, sometimes referred to as 2617R, has been very successful and Attwood has provided the opportunity for people to see a “real” ’60s GP driver performing in a period machine.

Driving the Attwood P261

Driving a period car is always exciting. Driving a winning period car is even more exhilarating, though it tends to make you slightly nervous. When the car’s original driver owns the car and comes along to keep an eye on things…well, you can imagine what that might be like.

A few years ago when I was about to drive the ex-Stewart H16, JYS said: “better you than me!” This time it was by invitation from Mr. Attwood that the privilege came about. Chassis 2617 is now looked after by Mike Luck and his team at Classic World Racing from its premises in Redditch, and Mike kindly discussed it with Richard who agreed that we could have some laps in the car. This was at an HGPCA test day at Silverstone some months ago, when California-based Brit Garry Diver was going to test the car with a view to possibly running it at Goodwood later in the year. At the same time, Attwood himself was on the premises to test the Aston Martin DBR1, so it was shaping up to be a very interesting day.

Photo: Ferret Fotographics

The car was a little reluctant to start during the morning session, and people spinning into the gravel curtailed the amount of track time that was going to be available. Garry was struggling to get in many laps with the red flag coming out regularly, and then the BRM was not running on all cylinders, and the battery was changed without much improvement. As time ran short, Garry had to leave for a business meeting and I was sure the anticipation was all going to come to nought. As the afternoon wore on, Richard Attwood appeared to oversee the head-scratching, and I came up with a very rare mechanical suggestion: should we try the original battery again? Whatever the reason, that amazingly did the trick and the car fired up and sounded perfectly healthy, and with the view of Mr. Attwood in the rear view mirror, I motored gently onto the Silverstone track.

Well, not overly gently, as you need to keep the revs up to keep the engine running cleanly. Starting with a few easy laps to get some photography done, the tires, Dunlop Racing 5.50L x 13 on the front and 6.50L x 15 on the rear, warmed up slowly, and the most dominant feature is the sharp and crisp rasp from the 2-liter V8 just behind one’s ears! The car was easy enough to slide into and after a short time, you are very comfortable in this snug, encapsulating environment. I could foresee a little trouble in getting myself out, but this was no time to worry about that. However, it was easy to imagine what Jackie Stewart might have felt when the monocoque crushed around him in the Spa crash. There just isn’t that much room for it not to hurt. Stewart did say he urinated blood for weeks afterward so it must have been painful.

Nevertheless, the cockpit and the period seat in Tartan plaid is supportive, and all attention can be given over to driving. I was well aware that Garry hadn’t got in quick laps in his limited time, so this was the chance to do so. The rev counter sits behind the now removable steering wheel—they didn’t have that in period!—and the counter reads to 12,000 though it is now red-lined at 8500 rpm. Water temperature and fuel pressure appear in one gauge on the left, with oil pressure and temperature gauge on the right, and these were rock steady in both the slow and quicker laps. I had been warned that the plugs might oil up, but considered use of the throttle and the 6-speed gearbox managed to avoid any problems. The 6-speed box was very slick and not difficult to utilize. BRM boxes trigger a memory for me; Pedro Rodriguez drove a BRM with one in the Tasman and was asked at the end of his race how he got on with the 6-speed gearbox. His reply: “eeet has seex gears??!!”

However, no problem here, and even on Silverstone’s national circuit you can use all six with seeming endless flexibility. Once settled down in the cockpit, everything fell to hand. There is plenty of space between the pedals, and there isn’t a huge amount of breeze in your face at speed. There is a clever slot in the small screen to allow air through, though this is not distracting. Actually that hole was to allow access to the fuel filler but neatly serves the purpose of cooling the driver as well. There is a fuel tank over the driver’s legs as well as in the side pods, and these were connected by means of a switch that allowed the reserve tank to be used if necessary.

A few more laps inspire enough confidence to push a little harder, using some 8000 rpm. Everything works efficiently. The brakes get used twice in earnest on this circuit and respond smoothly. The torque is impressive and coming out of corners at 4000 rpm-plus sends this businesslike machine rapidly down the next straight. There is plenty of feel turning into all the Silverstone corners, again raising confidence. You have to imagine how good it looks when you are behind the wheel, but you know you are driving one of the significant cars of the mid-’60s. The sound is awesome, precision handling was neutral, but maybe I wasn’t going quick enough to provoke oversteer or understeer! It sounds fabulous speeding up or lifting off, and it feels every bit the important car that it is.

And how nice it was to come in at the end and be able to sit down with Richard Attwood to talk about what it was like. That was a rare opportunity not to be missed. Thanks, guys.

Oh, “six levels of separation.” The term came from John Guare…look him up.

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis: Welded and riveted full-length stressed-skin monocoque tailored for central exhaust

Suspension: Front: Wide-based lower wishbone, inboard mounted coil/spring damper; externally adjustable anti-roll bar. Rear: Long reversed lower wishbones, outboard mounted coil/spring damper; externally adjustable anti-roll bar

Steering: BRM rack and pinion with short track rods

Brakes: Dunlop solid discs outboard front and rear

Wheels: Rubery Owen cast magnesium, front 5.50 x 13 or 15, rear 7.00 x 13 or 15

Tires: Dunlop Racing tires

Wheelbase: 7 feet, 7 inches

Engine: From 1966, 1970-cc Type P60, or 2070-cc P60 V8

Transmission: 6-speed Type P62 transaxle

Acknowledgements/Resources

Many thanks to Richard Attwood and Mike Ostroumoff for use of the car, and to Mike Luck and Chris Schirle and Nick for help and patience on the day. www.classicworldracing.co.uk

Nye, D. BRM Vol.3 Amadeus Press,

W. Yorkshire UK 2008

Sheldon, P. And D. Rabagliati

Tasman Formula 1964–1970 St. Leonard’s Press

W.Yorkshire UK 1994