The two-mile marker whizzed by. My Achilles tendon strained as my foot tried to shove the accelerator through the floorboard looking for more speed. The mph indicator on my Garmin was slowly climbing. I hit the next quarter-mile marker and I was there. Now all I had to do was hang on. But a mile can be a very lonely trip in a fifty-year-old, two-cylinder machine with the tachometer pinned at 8,000 rpm.

And did I mention the searing heat?

My fascination with speed goes back as far as I can remember. As a kid, my room was filled with Hot Wheels and Matchbox and slot cars and automotive magazines. I’m sure I daydreamed about becoming a world champion racer, but it wasn’t to be. I went to college, fell in with the wrong crowd, and wound up becoming an orthopedic surgeon.

Then in the mid-1990s, something totally unexpected happened. I was in my apartment after a long day in the operating room, and there was a show on TV that mentioned something about the movie Johnny Dark. And it all came rushing back. That campy Tony Curtis film of 1954: There it was…the origin of my racing obsession. I remembered seeing that flick over and over again as a kid. Those cars Tony and the other guys were racing were over-the-top cool. I had been infected at such a formative age. And so it began.

For almost 15 years I have been collecting and racing vintage metal and fiberglass of the 1950s. I race with CVAR in Texas and with General Racing and HMSA on the West Coast. I’m generally the guy you’ll find in the middle of the pack. I made the conscious decision when I first went to driving school that my vintage racing was going to be about the cars and fun and friendships.

I had no desire to step into the smash-or-be-smashed world of modern sports car racing, and felt totally fulfilled by the vintage spirit of honoring the great cars and racers of the past…until I saw another movie.

The World’s Fastest Indian is a must-see. Released in 2005, the movie tells the real life story of New Zealander Burt Munro’s (played brilliantly by Anthony Hopkins) obsession to race his 1920s Indian motorcycle across the Bonneville Salt Flats. I’ll not spoil the movie for you except to say that Hollywood loves a winner, not a middle-of-the-packer.

When I left the theater, I had another curious flashback to my childhood. I closed my eyes and tried to picture my first bedroom. The slot cars and magazines and then, all at once, there it was. Stuffed somewhere in the middle of all of it was the Bluebird miniature that I suddenly recalled “racing” across the kitchen floor. I remembered the sound the car made from my mouth. It wasn’t the 2,500-plus horsepower of the Rolls Royce engine that flung Sir Malcolm Campbell across the salt, but at age 5, it still sounded loud, nonetheless.

Bonneville. That’s where I had to go next. The fastest place on earth. They’ve been making history there for 60 years, and many road racers have been right in the middle of it. Space does not permit a record-by-record accounting of road racers at Bonneville, but here’s a small list of some names you may have heard of: Phil Hill, Mickey Thompson, Stirling Moss, Carroll Shelby, Dan Gurney, Chuck Daigh, and Phil Remington. Note to you road-racing diehards…keep an open mind.

What is particularly intriguing about Bonneville Speed Week is that the event is virtually unchanged from the first meet held in August 1949. The salt is still flat and salty, and the competitors are still automotive innovators to the extreme. More than that, though, the sport is still 100 percent nonprofessional, unspoiled by corporate sponsorship and big business. Make no mistake, however, Bonneville is the gathering place for the world’s best speed-trialers. It’s what Formula One is to open-wheel racing: the pinnacle of the sport.

When I realized I had to become a part of it, I knew that mid-pack was not my plan this time. Bonneville is not a tribute event. It’s all-out racing. A race for the record books, and, with it, perhaps a small piece of automotive immortality.

Selecting a racing class and a specific car to run is a huge part of the process. There are hundreds of Bonneville records in cars ranging from streamliners to production cars to trucks to motorcycles. And within each class there are records for a wide variety of engine types and sizes. The Southern California Timing Association (SCTA) Web site (www.scta-bni.org) is a useful starting point, but the official rulebook is an absolute must. If you learn nothing else from this article, read the rulebook again and again and again and again before buying or building a car. Failure to do so will end in disappointment and poverty.

I am fortunate to have two great road racing buddies in Harold Pace (whose stunning photographs accompany this article) and John Furlow. Harold and John spent countless hours with me thumbing through the SCTA rulebook discussing possible cars I might take a shot with. In the end, the consensus was that I go with my first love…sports cars. Then it hit me. Why not try to set a record in a sports car from the 1950s? I could honor the past and hopefully rewrite a little piece of history. A dozen more hours thumbing through the rulebook with Pace and Furlow and I had my class…Grand Touring Sport (GT). This class is for production sports and grand touring cars.

I didn’t own a car that met the rulebook’s “production” requirements so the next question at hand was what should I buy? And another bolt of lightning hit me. My racing team was already trying to make the engine in my 1954 Devin Panhard more reliable. Why not build on the lessons we’d already learned and take a Panhard-powered car to the salt? And since the GT class does not allow for body modifications, the best selection had to be one with an originally aerodynamic shape. One Panhard-engined production sports car jumped out…the Deutsch-Bonnet (D.B.) HBR-5.

The 1950s front-wheel-drive French D.B. sports racers were light, nimble and aerodynamic to the extreme. Motivated by two-cylinder air-cooled Panhard units of 750-cc, 850-cc, and 1000-cc, D.B. became nearly unbeatable in its class in international competition. D.B. was first in class at Le Mans in ’53, ’54, ’55, ’56, ’59, and ’60. They scored five consecutive Mille Miglia class victories (1953-1957), four at Sebring (’53, ’54, ’56, and ’59) and two more in the Tourist Trophy (’53 and ’55). Even as late as 1959 and 1960 the little cars were class winners at the Nürburgring.

Taking advantage of their racing notoriety, D.B. built the HBR-5, a grand touring sports car aimed at the American market. Hundreds of units were sold in the U.S., and some even found their way to the racetrack, slicing through the air with great aplomb. When Road & Track tested the HBR-5 in December 1957, its Tapley data (a measure of drag) was quite favorable.

There was one small problem, though…where would I find one? I emailed all of my Panhard and D.B. friends around the globe, but didn’t have any luck locating a car for sale. Then I contacted Myron Vernis who had two HBR-5s in his collection. Myron is a huge D.B. fan and was not at all interested in selling either of his cars. That is until Myron found out what I had in mind. He loved the idea of a D.B. running at Bonneville and immediately sold me chassis number 1025. This car, built in 1959, was SCCA-raced throughout the 1960s.

Then the hardest part of the project was upon me…convincing my curmudgeon-of-a-chief-mechanic, Greg Lucas, to build the car. Lucas had more hours than he (or I) would like to admit in Panhard engine preparation. Truth be told, the little French two-cylinder monster had exploded on us multiple times in the past. After much cajoling, Greg agreed to take on my project. We are men of great stupidity and conviction and (foolishly) refused to give up. Our team decided to focus all efforts on the GT record for the J engine class (under 750-cc), so Lucas went to work.

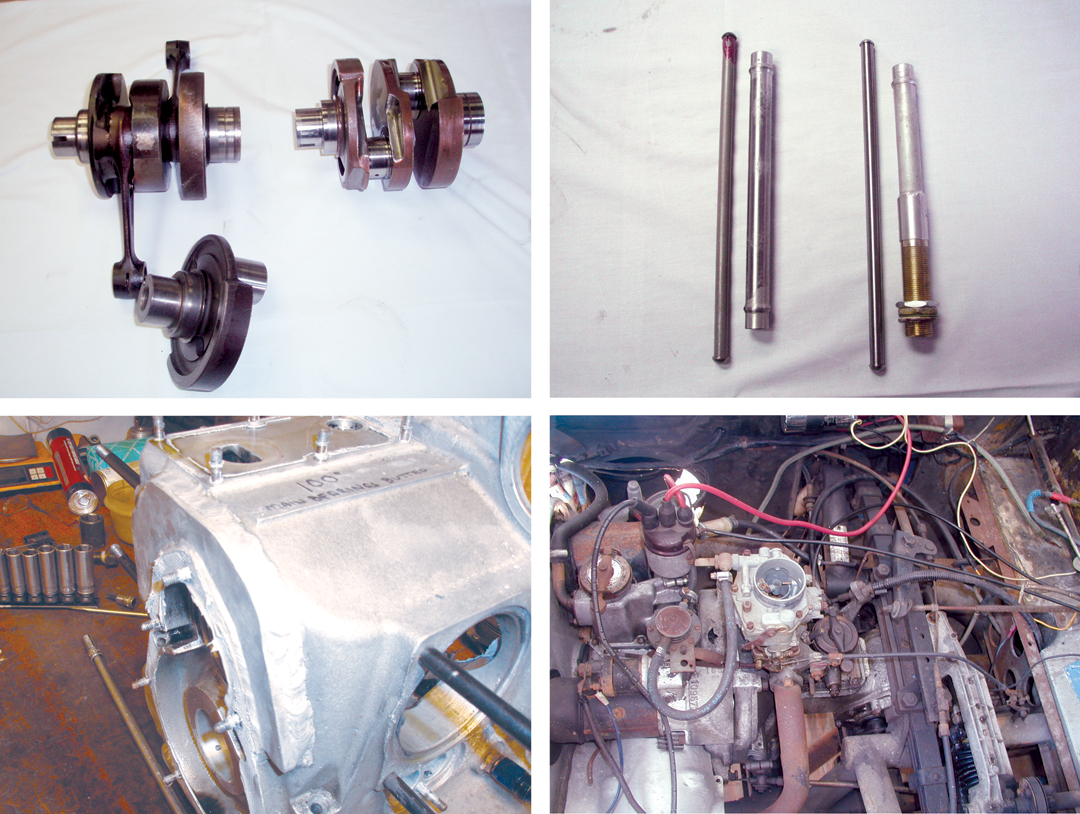

Several hundred hours later he had prepared the car and developed the tiny two-banger within an inch of its life. Nearly every internal engine component had been specially modified or built for the project. The crankshaft was thoroughly re-engineered. What was once a two-piece push-together crank was now a one-piece billet unit with custom two-piece roller bearings. The rods were re-engineered, lightened and strengthened and the pistons were all new. The valve train and heads were improved to the extreme with titanium this and beryllium that everywhere. Whereas a stock 750-cc Panhard power plant revs to the mid-5000s, Lucas created an engine capable of an honest 10,000 rpm with nearly a three-fold increase in power output.

Mark Evans “massaged” the 50-year-old fiberglass body, painted the car, and did much of the fabrication and prep work. Jeff Gee constructed the roll cage and built various other one-off pieces. He also took on the role of the shop’s psychologist, keeping the guys calm whenever a dyno run resulted in scattered engine parts. Dan Barton, an engine guy extraordinaire, was responsible for critical machine and head work on the engines. Walt Bobo, Mike Hart, Tom Thrash, and many, many others wandered in and out of Lucas’ shop offering advice and support along the way. Mike Miller did the wonderful airbrush artwork.

In early August we loaded the car into the trailer. Days later we made the final two-hour jaunt from Salt Lake City to Bonneville. The drive to Bonneville is exotic and surreal in a barren sort of way. As you travel along the highway, vegetation gives way to a progressive white-out with the occasional tall mound of what must be snow. But there is no melting out here and eventually your brain accepts the unlikely truth…it’s all salt.

As you approach Bonneville Speedway, the highway bisects what appears to be thousands of acres of salt. But it is an illusion. Take the several mile one-laner that leads to what is known as “the end of the road” and you are just beginning to get an idea of the enormity. Drive onto the salt and another few miles to line up for tech inspection. Now you are really there. The highway has vanished. All signs of civilization are gone. There are miles and miles and miles of perfectly flat dry salt in every direction. No birds in the sky. Not a single shrub or worm. Look out onto the horizon and for the first time in your life observe the actual curvature of the planet. Welcome to Bonneville, my friends. Welcome to the surface of the moon.

If you’re planning on making the trip to Bonneville there are some things you need to know. First and foremost, the sun is without mercy. Seriously rated sun block and a silly hat are a must. The salt is actually cool to the touch but this is a trap. The sea of white is totally reflective and third degree burns on the under surface of the nose and the crotch area (don’t wear shorts!) are unfortunately common. Second, there is no running water. Figure out how many bottles of water you need, then double it and add ten more bottles. Don’t worry about over-serving your bladder. Port-O-Lets are plentiful.

Tech inspection is a legendary ritual at Bonneville, and it’s like nothing you’ve been through at a vintage road racing event. The total focus is on safety, and the SCTA inspectors are serious about their job. Cars are gone through nose-to-tail, and a full inspection can take several hours. At this time no mention is made as to whether a car is legal to set a record. That process happens later, if you break one.

My crew and I waited in line much of the day before pushing under the inspection tent. Our inspector made a few suggestions for next year, but we passed without any real drama (others were not so lucky). One thing we did that I highly recommend for any B’ville newbie is to get an experienced racer or inspector to pre-inspect your car while it’s under construction. Ed Stuck drove all the way from Dallas to Houston to inspect our car in June. He pointed out several “instant fail” items and gave us a punch list of needed fixes. As a result of Stuck’s kindness, we cleared tech in less than 30 minutes.

And then the day to race was upon me. For those of you who have never roared across the salt, there is more going on than meets the eye. First, the temperature during the day can get as high as 110 degrees, which some engines (such as a two-cylinder air-cooled dwarf) are not so fond of. Second, the effective altitude can approach 8000 feet above sea level, and setting carburetion and getting an engine to make power can be a bitch. Third, racing on salt presents challenges in regards to traction and tire slippage, and cars tend to wander side to side.

We unloaded the car (now known as “BoneEvil”) from the trailer and Lucas re-jetted the carbs based on weather conditions. Motivated by a push-truck we headed toward the racecourse.

Photo: Harold Pace

The course I would run is called the short course. It measures three miles in length and is for cars incapable of 175 MPH (we felt we were safe). The speed recorded is not the top speed attained but is the average speed sustained between the 1st and 2nd mile or the 2nd and 3rd mile markers, whichever is faster. In order to break a record, you must have a successful qualifying run that betters an existing mark. If successful, your car is then placed in impound with a sealed gas tank. The following morning you make a record run (also known as the backup run). If your two-run average is faster than the existing record, you head back to the tech area where they pump your engine and officially certify your record.

As I came to the starting line for my first-ever run, I recalled that the existing record for GT/J had stood at 80.143 mph since 1992. Suddenly it hit me. What the hell was I doing out here in a car built half a century earlier?

All belted in, engine revving, the starter gave me the go-man-go signal. I spun the tires hard and took off with everything I had on tap. I don’t believe racing across a 105-degree sauna is what the French had in mind when they built the HBR-5. And I don’t think the little car enjoyed the thinny-thin-thin air all that much. But I must tell you, BoneEvil is a car with a lot of heart. Those two little pistons huffed and puffed and pulled with all of their might. As my GPS speedo climbed, so did my breathing and heart rate. It’s exciting being out there, just you and the vast expanse of salt. There’s so much history to the event. And now I had a chance to become a part of it forever.

As we stared at the timing slip after the run, Lucas, Evans and I were speechless. My average speed from mile 1 to 2 was 80.739 MPH, and from 2 to 3 was 93.070 MPH. We hadn’t just qualified; we’d crushed the existing record.

Off we went to impound where the car would rest until the next morning. The three of us, however, were anything but restful. In typical Lucas fashion, Greg reviewed each and every disaster that might befall us the next day. Would the car perform well? Would the engine grenade? Would we pump under 750-cc?

We arrived at impound at 6 a.m. the following morning (August 19, 2008) and paced around nervously for 30 minutes. The sunrise at Bonneville is beyond comprehension. It’s one of those visions that bring out the Forrest Gump in all of us. At around 6:45 a.m., the SCTA officials lined all the record qualifiers up and we caravanned to the course.

Pushing BoneEvil toward the starting line, I couldn’t help but think about the history that’s been made upon this hallowed salt. Then, before I knew it, we were off and running. She liked the cool morning air and the power seemed to pour forth a bit more freely. By the one-mile marker I had the car in fourth gear and my right foot was solidly planted. I was accelerating harder than the qualifying run and as the car surged forward I began to relax. It’s pure joy being flat out at Bonneville, particularly when you’re about to re-write history.

We cleared the post-record inspection and the engine pumped out at 740-cc. With the average speed from mile 2 to 3 clocked on this day at 94.918 MPH, the two-run average landed us a new record of 93.994 MPH. It was a moment of pure elation. Even Lucas smiled.

Looking back, it really made little sense to go for a land speed record in such an antiquated machine. After all, Grand Touring Sport/J is not a vintage class. It’s open to any and all modern sports cars with an engine under 750-cc. But I’m a vintage guy, and I guess I wanted to make a point about these fantastic old cars we love. Move over modern tuners. The Deutsch Bonnet HBR-5 of the 1950s is the fastest under-750-cc production sports car of all time!